W.E.B. Dubois vs. Booker T. Washington (Round 1)

Support African Elements via Patreon at patreon.com/africanelements

*Ad-Free Videos for as little as $1/Month Subscription!!*

After the failure of Reconstruction, African Americans in the post-Civil War era confronted many problems, and Black leaders responded in various ways. Some advocated leaving the South for the Western frontier, others responded with agitation and protest, and others responded with an accommodationist approach. W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington approached the world in ways that fundamentally opposed one another. This series will explore a variety of philosophical ideologies, assessing their strengths and limitations. It will begin with a critique of W.E.B. DuBois’s framework of Civil Rights through the lens of his rival, Booker T. Washington.

W.E.B. Du Bois, Political Activism And Civil Rights

After the Civil war, the 14th Amendment of the U.S. constitution promised Black Americans citizenship and equal protection under the law. Nevertheless, many states continued to deny Blacks access to public facilities such as parks, libraries, swimming pools, theaters, restaurants, hotels, hospitals, and even cemeteries.

Codified In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racial segregation was legal under the Constitution based on the notion of “separate but equal.” By design, the collection of laws known as Jim Crow kept Blacks from gaining full political representation by denying them voting rights and other fundamental human freedoms. They also sought to prevent interracial marriage between whites and Blacks. Some African American leaders pushed back by asserting their rights as citizens. Such an approach is known as the philosophy of Civil Rights. W.E.B. DuBois became a leading advocate of Civil Rights in the early twentieth century.

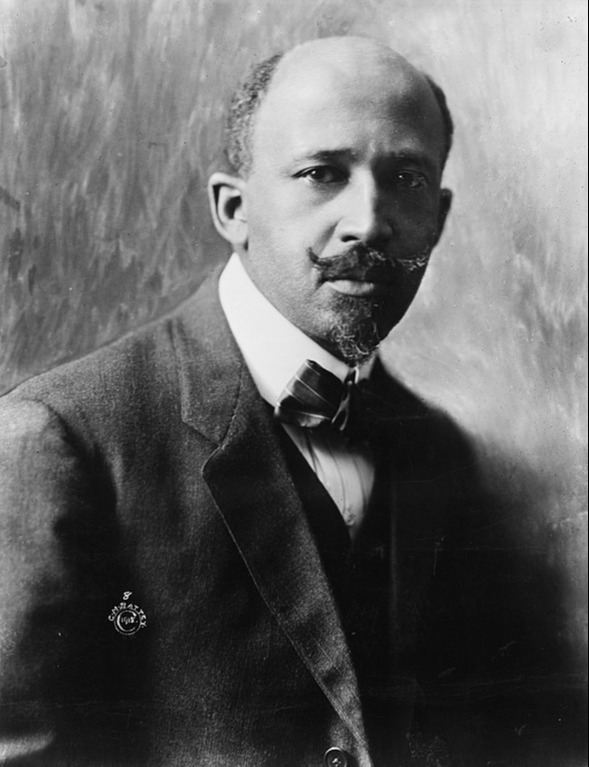

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan Africanist, and author. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on February 23, 1868, Du Bois grew up in a generation with no direct experience with legalized slavery. After graduating from Fisk University in 1888, he attended Harvard University, where he became the first African American to be awarded a Ph.D. from the University in 1895. He taught at Atlanta University from 1897 to 1910 and again from 1934 to 1944. Du Bois emphasized a liberal arts educational philosophy that stressed the importance of sociology, history, and philosophy. His work as a civil rights activist emphasized political equality by attacking the systemic denial of political rights the Black Community continued to experience.

To that end, Du Bois and 28 other delegates met at Niagara Falls in 1905. The Niagara Movement sought to end segregation and discrimination against Blacks through nonviolent means. It also called for equal access to public facilities such as schools, libraries, parks, transportation systems, etc., regardless of race or color. Their strategy was one of public protest and agitation. The NAACP confronted the power structure, making it difficult to continue the status quo so long as systemic political and social white supremacy was in place. They staged marches, petitioned lawmakers, and wrote editorials in newspapers constantly reminding the white power structure of the injustice of the racial subjugation of American citizens. They demanded full political rights and social equality, equal treatment in public places, and an end to discrimination and segregation throughout the United States, including the U.S. military.

In doing so, he forwarded a notion of the “talented tenth.” It was the talented tenth amongst Black intellectuals that, armed with a liberal arts education, Du Bois believed was most capable of moving Black America forward by deconstructing the social barriers that held back the Black community. It was DuBois’s focus on race relations, economic inequality, education, and politics that contrasted most sharply with Booker T. Washington’s emphasis on practical education and industrial training.

In 1903, Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of essays that explored the history of blacks in America and their struggle for freedom. One chapter in particular specifically called out Booker T. Washington and critiqued his approach to Black progress.

Booker T. Washington, Self-Help And Racial Solidarity

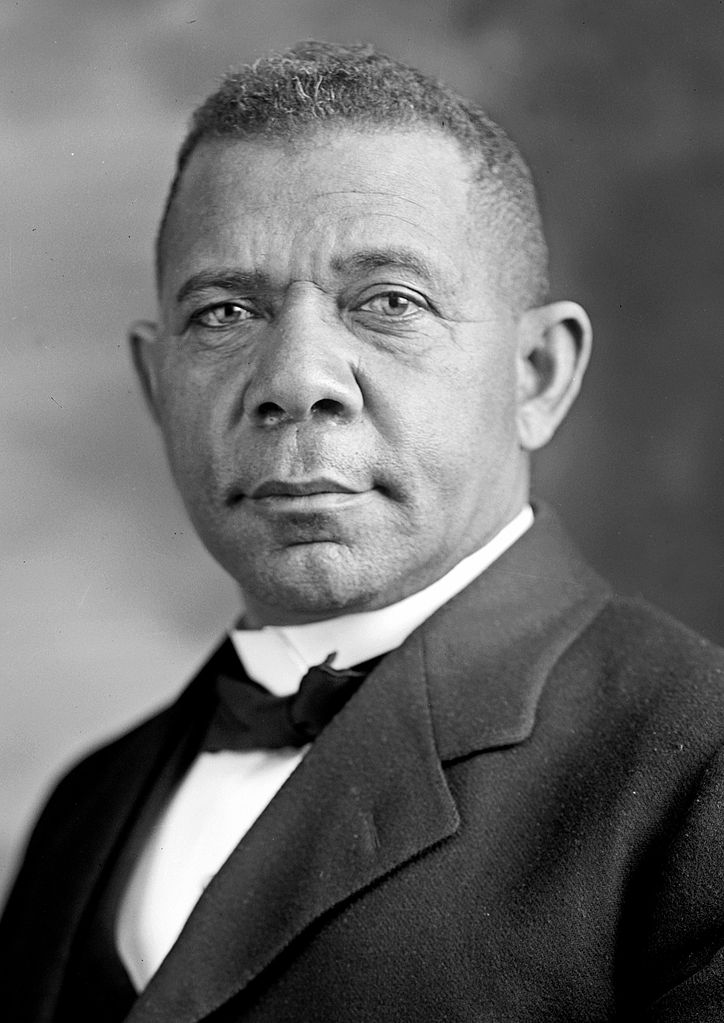

W.E.B. Du Bois’s contemporary and rival, Booker T. Washington, was born into slavery in 1856 on a plantation in Franklin County, Virginia. Contrary to Du Bois’s vision of social justice and integration for Black Americans, Washington believed it better to remain separate from whites than attempt desegregation. As a native of the South who had experienced slavery firsthand, Booker T. Washington viewed Du Bois and his strategy of protest and agitation for civil rights as impractical and dangerous. From Washington’s standpoint, public demonstrations were especially reckless after the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan, which threatened violent reprisal and even death for the most trivial of social missteps.

Washington opposed the Niagara movement and sought to undermine it in every way possible. First, Washington sent spies to keep him informed as to the organization’s participants. He then paid the newspapers to criticize the movement and to ostracize anyone who took part in it. Washington’s political influence and close ties with the white establishment allowed him to work behind the scenes shut out people who supported the Niagra movement by ensuring their exclusion from federal appointments and jobs.

Ultimately, Washington was successful, and the Niagara movement disintegrated before it got off the ground. Nevertheless, Du Bois continued his efforts when he and other key players from the Niagara movement founded the National Organization for the Enhancement of Colored People or NAACP in 1909. Their tactics included a reliance on judicial and legislative measures to provide legal protections for African American citizenship. It was a tactic the NAACP used consistently.

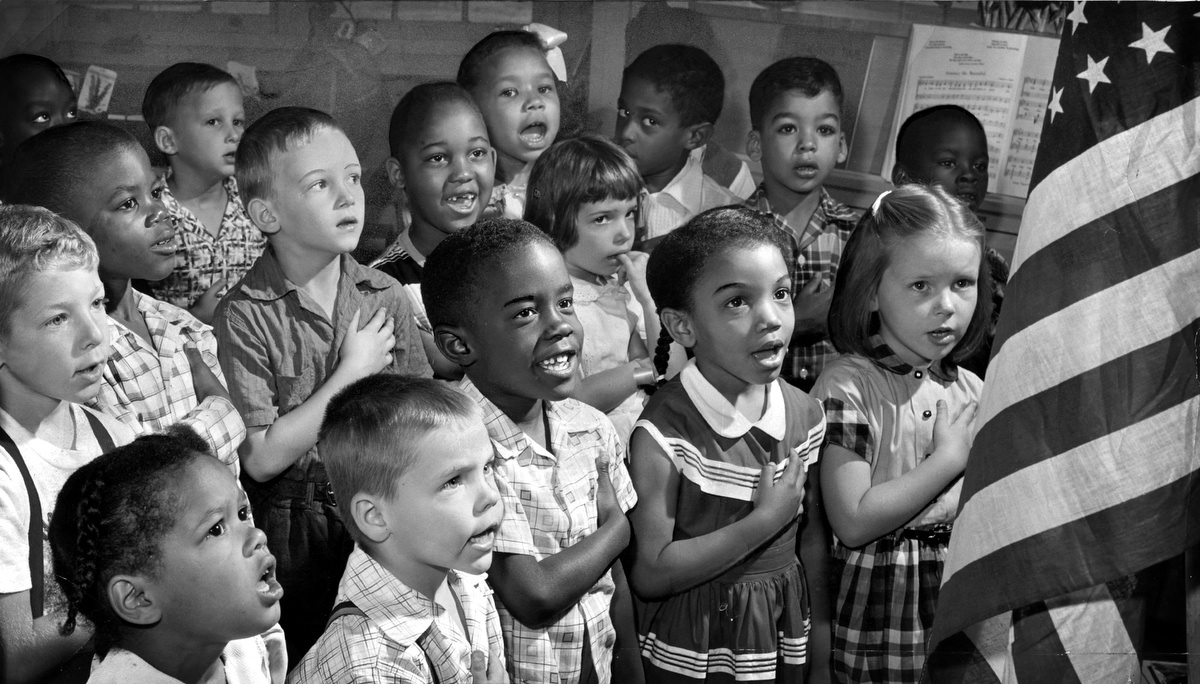

Their initial success came in the NAACP’s attack on the “grandfather clause,” which Southerners used to keep former slaves away from the voting booths. In 1915, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the grandfather clause in Guinn v. The United States. The courts became the NAACP’s primary weapon to such an extent they established a separate branch of the organization in 1940. With its own legal staff, the NAACP Legal Defense And Education Fund continued its assault on legalized segregation from the mid-twentieth century onward. Later, several strategically formulated lawsuits culminated in the famous Brown v. Board of Education decision. The 1954 case overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine that codified legal segregation in the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896.

While the NAACP has much success to its credit, it is essential to be realistic about the meaning of those successes. For example, after Guinn v the United States outlawed the “grandfather clause,” the all-white primary quickly replaced it. The “white primary” effectively rendered the Black vote meaningless by barring Black candidates from running in primary elections. After Smith v. Allwright outlawed the “white primary” in 1944, other methods of voter disenfranchisement quickly filled the void. Even in the NAACP’s best-known legal victory, Brown v Board of Education, the limitations of the integrationist approach become visible.

The unanimous 1954 Supreme Court decision reversed Plessy v. Ferguson and overturned legally sanctioned segregation. Nevertheless, in 2004, the Harvard Civil Rights Project conducted a study to assess the decision’s impact. The study concluded that 50 years after the landmark case, school integration was at the same level in 2004 as in 1969. According to the report, one in eight southern Black students attends a school that is 99 percent Black. About a third attend schools that are at least 90 percent minority, including more than half of African Americans attending schools in the Northeast. The report concluded, “We are celebrating a victory over segregation at a time when schools across the nation are becoming increasingly segregated.” (Orfield 2004)

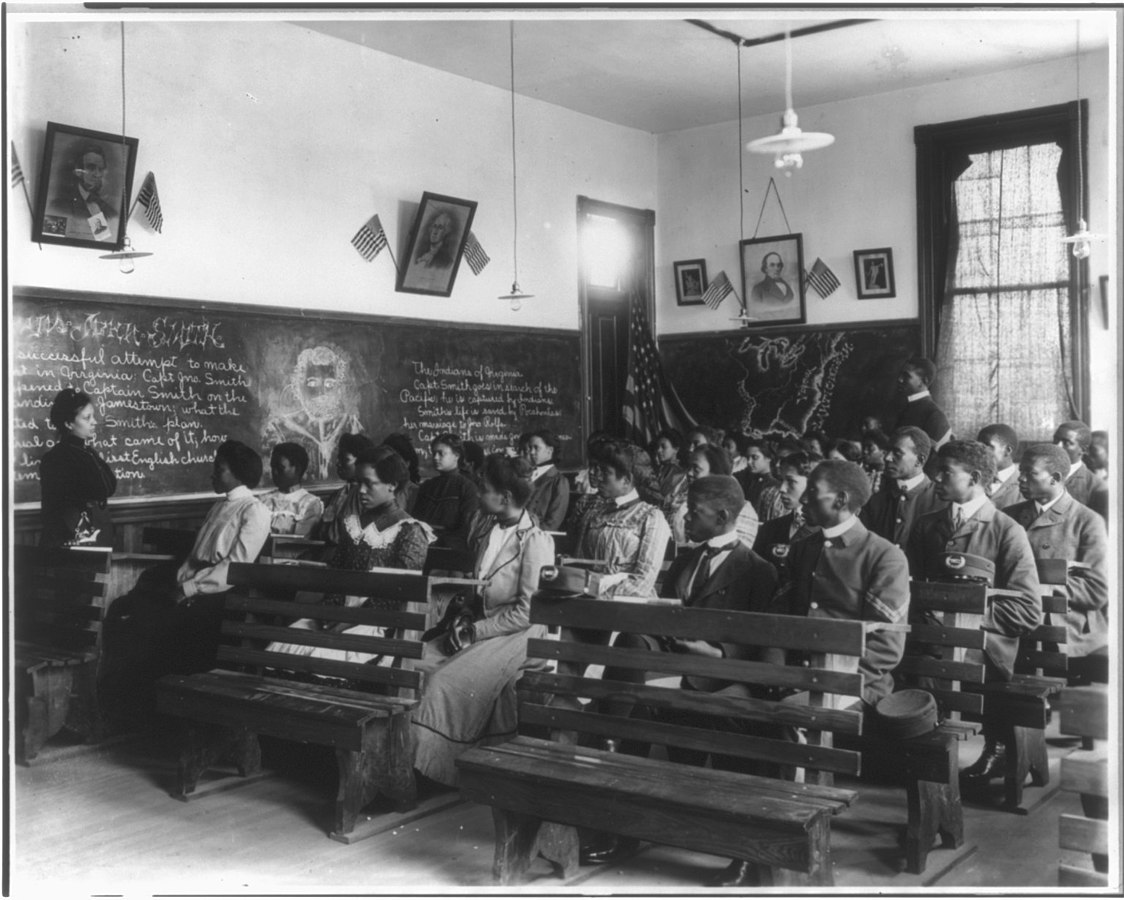

It is here that one sees a potential advantage that Booker T. Washington’s approach had over Du Bois’s approach. Washington’s ideology didn’t rely on desegregation or a court system in which every “victory” advanced one toward an ever-receding goal line. Washington didn’t concern himself with dismantling “Jim Crow,” attending white schools or sitting at white lunch counters. Instead, his goal was to build economic independence. Through industrial education at his own Tuskegee Institute (later Tuskegee University), Washington sought economic progress by having the Black community establish its own Black colleges and build their own lunch counters in their own separate Black America.

Furthermore, whereas Washington remained neutral concerning Black people’s involvement in US military conflicts, W.E.B. DuBois wrote an editorial calling for Black Americans to “close ranks” and support the United States during World War I. Because Blacks were still denied civil rights in the United States, he was widely criticized for not taking the opportunity to demand racial justice.

We of the colored race have no ordinary interest in the outcome. That which the German power represents today spells death to the aspirations of Negroes and all darker races for equality, freedom, and democracy. Let us not hesitate. Let us, while this war lasts, forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy. (Taylor 25)

Du Bois faced criticism because of the contradiction he observed only a few years earlier in a 1914 edition of The Crisis. Whereas the Buffalo Soldiers protected the white frontier settlements,

This made for a contradictory situation, as Du Bois observed about Nogales, Arizona. While there were a plethora of “colored troops” there and also “several large property owners among the colored people,” the “colored children of this town” had to adhere to “the state law [that] requires separate schools for white and colored.” (Horne 53)

Was it realistic to expect Black people to gain respect, citizenship, and equality in return for loyal military service? Furthermore, the experience of the Buffalo soldiers begs the obvious question: was it feasible for Black people to expect to gain the respect of whites while marching under a banner of white supremacy? In this round, we looked at the philosophy of integration and critiqued its limitations through the framework of Booker T. Washington’s approach. In round two, we will take a closer look at the strengths and limitations of Booker T. Washington’s philosophy. In the meantime, who won this round?

SOURCES

Horne, Gerald. Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920. New York University Press, 2005.

Taylor, Quintard.From Timbuktu to Katrina: Readings in African-American History. Boston, Mass: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008. Print.