African Elements

Black History, Politics, and News

Black History & Politics Online Video and Educational Material

The video material, resource guides, and lesson plans on this website can be used for free in Black History and Africana Studies educational courses and syllabi.

Videos are captioned and accessible. Teachers and students of all grade levels may share and embed these online materials for free. However, the content cannot be used for commercial purposes.

About

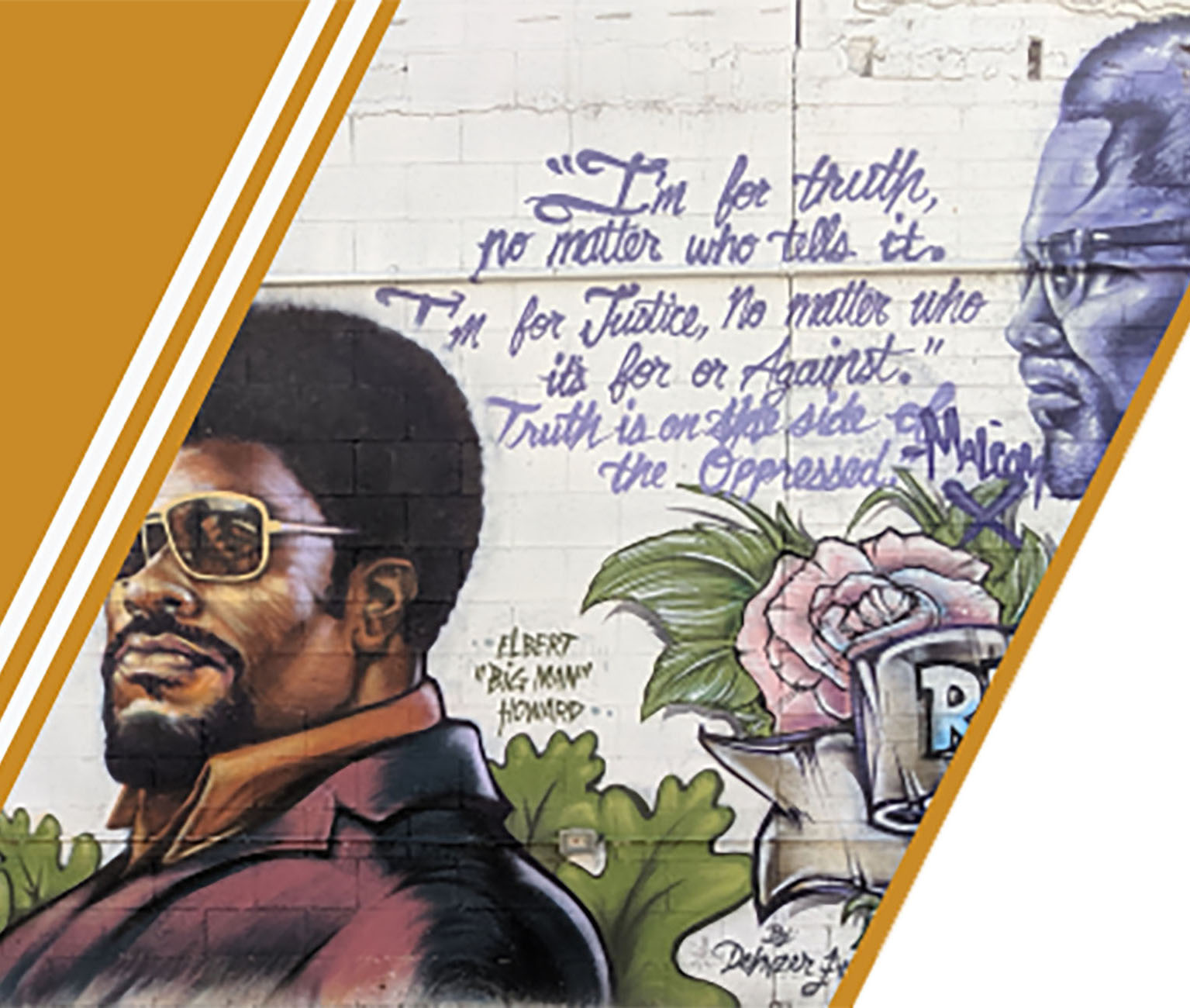

Darius Spearman has been a professor of African American history, Black Culture, and the African Diaspora for over 20 years. He began his teaching career in 1999, and since then has taught courses in American Culture, Race, Gender, & Ethnicity, Civic Engagement, The Black Family, and African American History. As a career educator his goal is to create accessible curriculum resources on Black Americans for students and teachers of African American History to foster opportunity in education.

Become a Patron

Support us on Patreon

Unlock member benefits! Gain early access to videos and educational materials while supporting Black Studies curriculum development by becoming a member.