Blood and Coal: The Deadly Cost of Fighting Mining in South Africa

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Introduction: When Speaking Up Becomes Deadly

In October 2025, a Johannesburg public hearing turned into a courtroom of conscience. Environmental coalitions such as Life After Coal and Earthlife Africa presented testimony on the killings and disappearances of anti-mining activists across South Africa. Their stories painted a landscape of fear shaped by race, corporate greed, and government inaction (Mongabay).

From KwaZulu-Natal to the North West Province, community leaders opposing coal, gold, and iron mining have been systematically targeted. Reverend Mbhekiseni Mavuso testified, “We are just waiting to die at any time because nobody is protecting us.” His colleague, Mbhekiseni Dladla, was assassinated in 2024 for challenging the Melmoth Iron Ore Mine. These killings highlight how resource extraction in Black communities has become a matter of life and death (Mongabay).

The Pattern of Violence Against Environmental Defenders

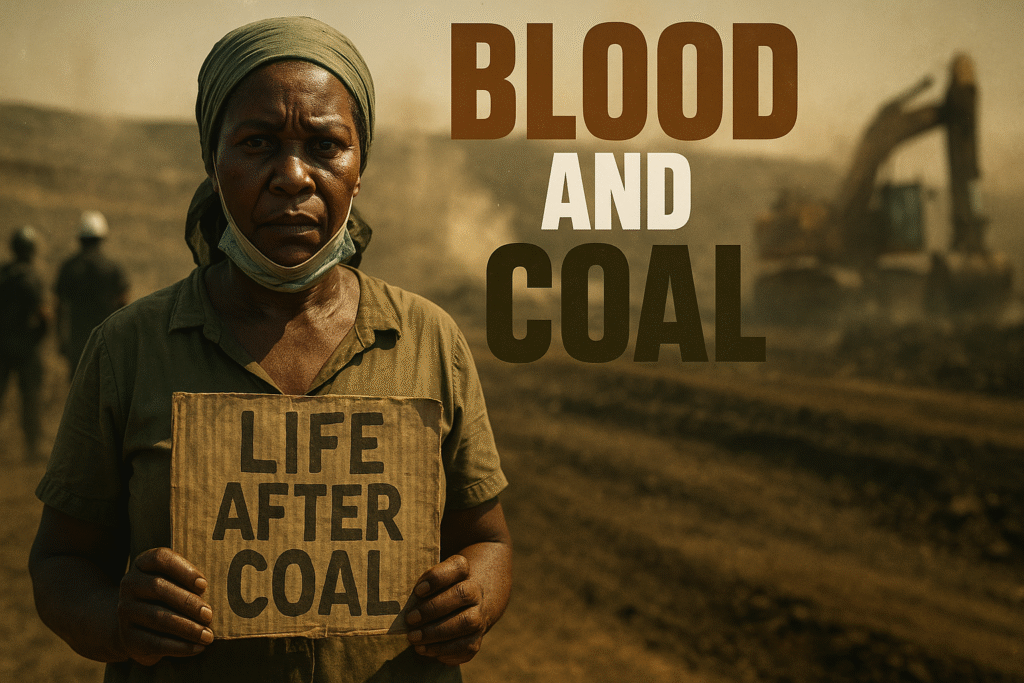

What began as isolated tragedies has become a recognized pattern. Since 2016, more than two dozen environmental and land defenders have been murdered in South Africa. Activists opposing mining expansion describe hitmen on motorcycles, anonymous police raids, and midnight visits from corporate security. These tactics echo the apartheid-era methods used to silence Black resistance.

Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe was killed in 2016 for leading opposition to titanium mining on ancestral Xolobeni land (IndustriALL). In 2020, Fikile Ntshangase, who refused to sign a relocation contract with Tendele Coal Mine, was shot in front of her grandchild (FairPlanet). More recently, Shawn “Paps” Lethoko, a leader of artisanal miners’ rights, was assassinated in October 2025 (WWMP).

Communities Under Siege: The Health and Environmental Cost

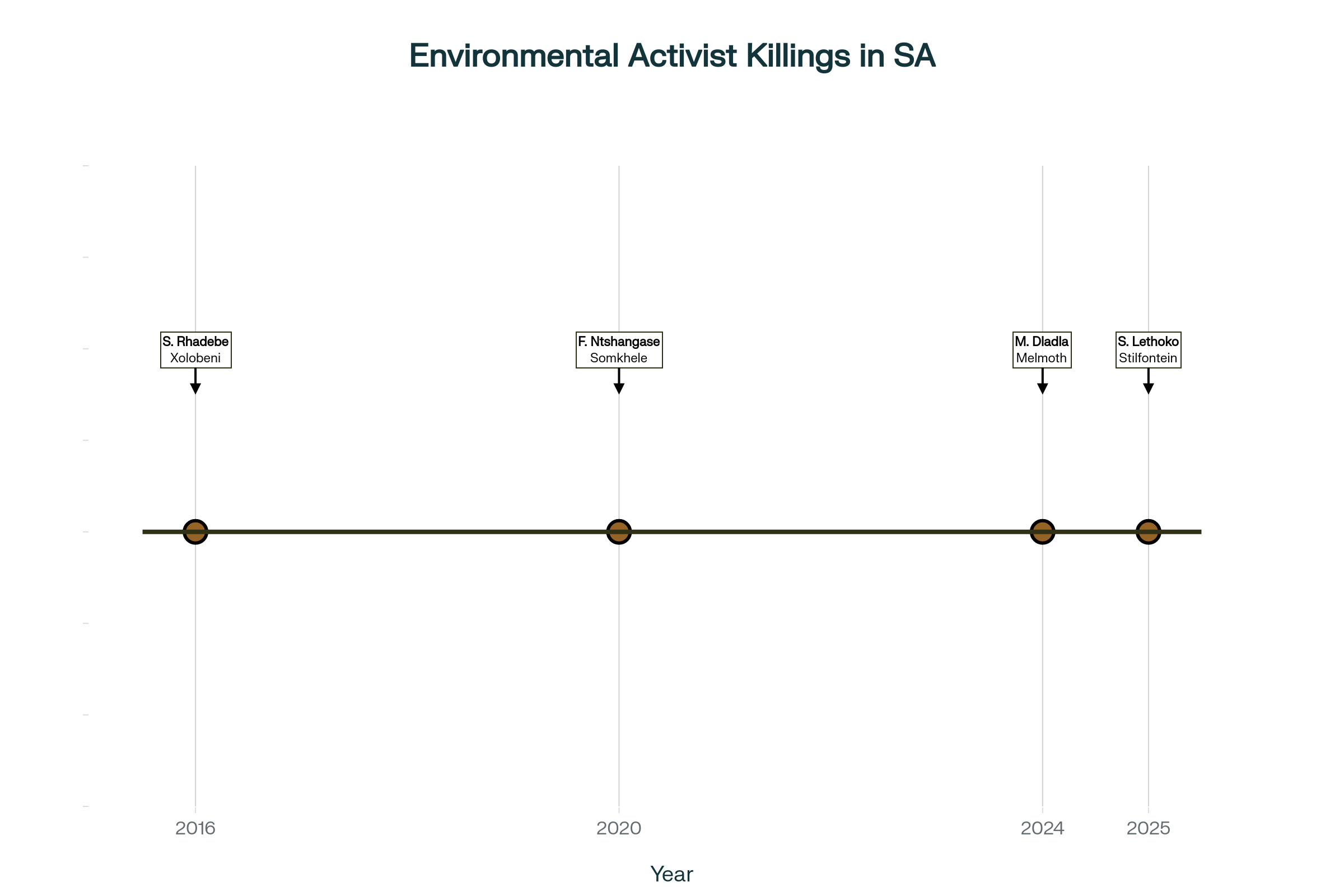

Beyond direct violence, mining devastates local ecosystems and health. In coal towns such as Phola and Somkhele, studies by the Centre for Environmental Rights found that 98 percent of residents reported dust exposure, 96 percent experienced water contamination, and 95 percent suffered respiratory illness related to coal pollution (CER).

Those most affected are Black South Africans living near extraction sites. Generations of displacement under apartheid placed these communities at the ecological margins—where corporate mining now expands. Women, in particular, shoulder the weight of survival, walking long distances for clean water while facing sexual violence near mining zones (CIEL).

The Deep Roots of Extraction: Colonialism and Apartheid

Mining’s violence is inseparable from the history of South African colonialism. Since the discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in the 1860s and gold in the 1880s, Black labor has powered the industry while reaping none of its rewards. Laws like the 1911 Mines and Works Act cemented White monopolies on skilled positions, while Black workers toiled underground for survival wages (Media+Environment).

Under apartheid, mining magnates partnered with the state in a racialized system of extraction. Pass laws, forced removals, and corporate compounds ensured a steady supply of cheap Black labor. By the late 20th century, entities like Anglo American controlled most of the economy’s assets, built on the backs and lungs of African workers (Phenomenal World).

Key Term: Environmental Justice

Environmental justice is the principle that all people, regardless of race or income, deserve equal protection under environmental law. In South Africa, it confronts how pollution, displacement, and climate risk overwhelmingly target Black communities.

The concept links ecological well-being to racial and economic equity, acknowledging that protecting the environment also means protecting lives.

Why This Matters Today

The struggle in South Africa mirrors global battles across the African diaspora—from the Niger Delta to the Amazon—where corporate extraction continues to spill Black and Indigenous blood for profit. Environmental defenders stand at the front lines of both ecological and racial justice. Their courage reminds us that fighting for the planet means fighting for people.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of Between the Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. Visit Darius online at africanelements.org.