Listen to this article

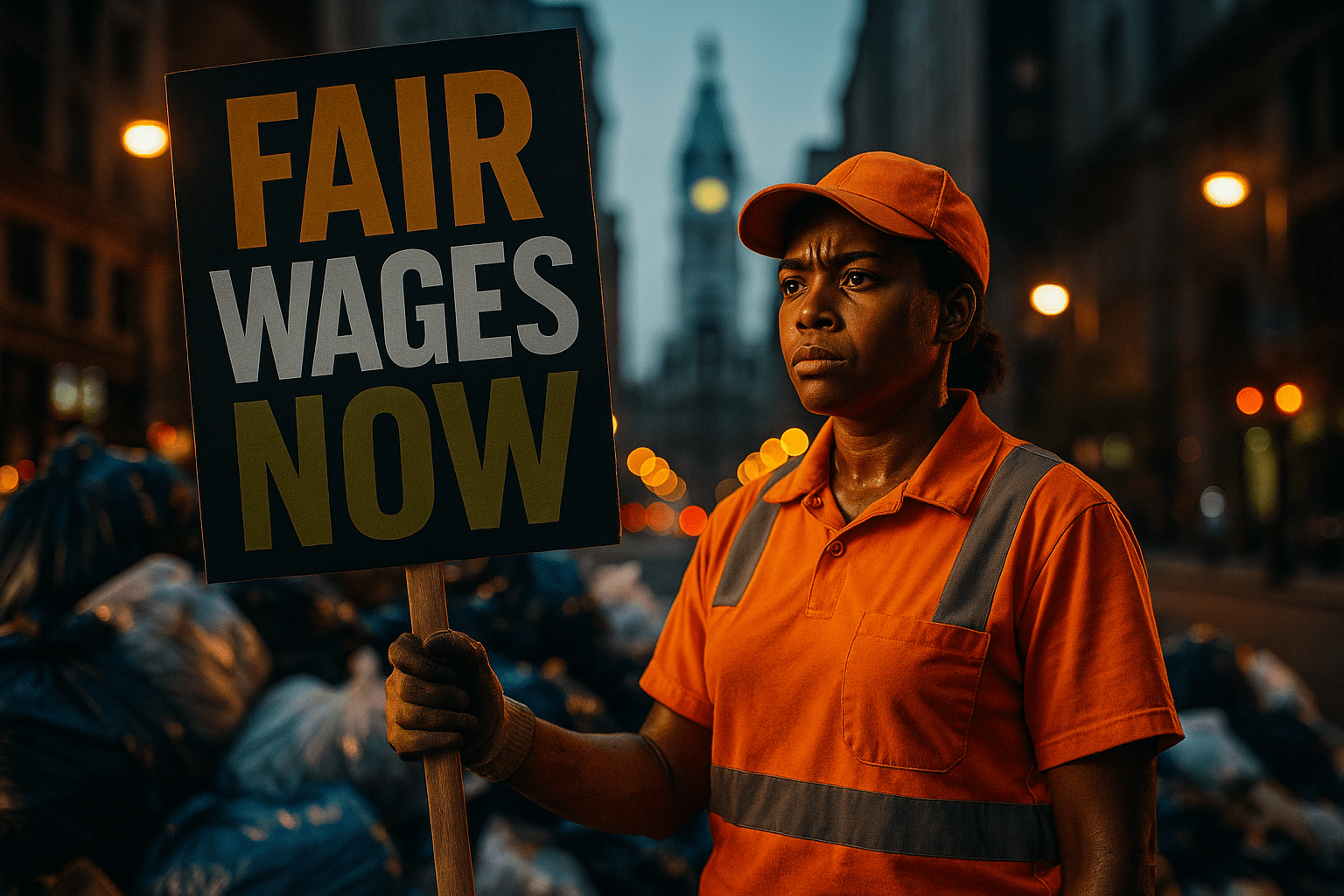

Download AudioPhilly Worker Strike: A Fight for Fair Wages

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Philadelphia’s Piles of Protest

As the Philadelphia municipal worker strike enters its second week, a stark visual reminder of the ongoing labor dispute has emerged across the city: the so-called “Parker piles.” These large collections of uncollected garbage, accumulating in residential neighborhoods, are a direct reference to Mayor Cherelle Parker, under whose administration the strike is occurring and the trash is piling up (inquirer.com). The visible impact of these growing mounds of refuse highlights the immediate disruption to daily life for Philadelphia residents.

The strike, which began on July 1, 2025 (inquirer.com), involves the AFSCME District Council 33 union, representing approximately 9,000 blue-collar city workers. This union, known as DC 33, is Philadelphia’s largest union representing city workers and is an affiliate of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), a national labor union for public service employees in the United States (WHYY.org, WHYY.org). Their members include essential personnel such as police dispatchers, trash collectors, water treatment plant operators, and employees in the streets, sanitation, parks and recreation departments, as well as correctional officers and Philadelphia Housing Authority employees (inquirer.com, inquirer.com). This current labor action is particularly notable as it marks the first time in the history of labor relations between the City of Philadelphia and AFSCME District Council 33 where social media is playing a significant role in how the struggle is unfolding (inquirer.com).

The Union’s Unwavering Stance

The AFSCME District Council 33 union has taken an aggressive stance leading up to and during this strike. DC 33 President Greg Boulware, who assumed his role after a union leadership fight, has been determined to secure “life-changing raises” for his members (inquirer.com). This resolve was clearly demonstrated two weeks prior to the strike when Boulware held a strike authorization vote. An overwhelming 95% of DC 33 members supported this measure (inquirer.com, inquirer.com).

A strike authorization vote is a formal process where union members vote on whether to give their leadership the authority to call a strike if contract negotiations fail. The high approval rate seen with DC 33 signifies strong member solidarity and a clear mandate for aggressive negotiation tactics. This vote empowers the union leadership to take decisive action, including initiating a strike, to achieve their demands. The union is using platforms like Instagram to disseminate their message, and citizens are expressing sympathy and support for their cause, further bolstering the union’s position (inquirer.com).

The Weight of Wages and Living Costs

At the heart of this labor dispute are the wages of DC 33 members, who are currently the lowest-paid among Philadelphia’s major municipal unions (inquirer.com). The average salary for a DC 33 member is approximately $46,000 per year (inquirer.com). This figure becomes particularly stark when compared to the cost of living in Philadelphia.

According to MIT’s Living Wage Calculator, a single adult with no children needs at least $48,000 annually to reasonably support themselves in Philadelphia. This means the average DC 33 member earns $2,000 less than what is considered a living wage in their own city. Sanitation workers, specifically, earn between $42,500 and $46,200 annually, which translates to $18 to $20 per hour. These wages are reported to be the lowest among major U.S. cities, with hourly wages for similar positions in other cities ranging from $21 in Dallas to $25-$30 in Chicago. For many Black and brown families in Philadelphia, who often bear the brunt of economic disparities, these wages make it incredibly difficult to secure housing, food, and other basic necessities, underscoring the urgency of the union’s demands.

Annual Wage Comparison for City Workers

City Services Under Strain

The strike has significantly impacted city services, leading to widespread disruptions and visible signs of strain. Trash collection has been severely affected, resulting in the aforementioned “Parker piles” of garbage accumulating in neighborhoods (inquirer.com). While city officials detailed a contingency plan for trash collection, including establishing 63 neighborhood drop-off sites (WHYY.org), the sheer volume of uncollected waste remains a pressing concern for residents.

Beyond trash, other vital city functions are operating under what Mayor Parker terms “modified capacity.” This means that while many city services will remain operational, they will experience alterations, reductions, or slower response times (inquirer.com). City libraries and some city pools are closed due to the strike (inquirer.com), and city-run recreation centers are operating with reduced hours. Critical services like 911 dispatch are experiencing potentially slower response times (inquirer.com). The Philadelphia Water Department is operating with a reduced workforce, with staff being “cross-trained” to ensure drinking water and wastewater services continue uninterrupted (WHYY.org). However, the city has warned of service impacts and longer wait times for repairs concerning water services (WHYY.org). Tensions have also risen, with reports of slashed tires on city vehicles, open fire hydrants, and picketers blocking police from entering a trash yard (inquirer.com). A striking city worker was even arrested for allegedly slashing tires on a Philadelphia Water Department truck, causing an estimated $3,000 in damage (inquirer.com).

A History of Struggle and Sanitation Strikes

Philadelphia has a long and often contentious history of sanitation strikes, dating back to March 1937. These past struggles provide a crucial context for understanding the current dispute and the deep roots of labor activism in the city. A brief work stoppage in 1937 led to early discussions between city administration and an early version of the current union.

A more significant weeklong sanitation strike occurred in September 1938, prompted by layoffs of over 200 city workers. This period saw “street battles” erupt in West Philadelphia as strikers blocked police-escorted trash wagons attempting to collect refuse with replacement workers (inquirer.com). Philadelphia residents, many of whom were union members themselves from textile, steel, and food industries, rallied behind the strikers. Their support proved pivotal, leading to the strikers’ demands being met and the formal recognition of AFSCME by the city. This 1938 strike was a major event, demonstrating the potential for violence and significant public health concerns associated with garbage strikes. Another two-week trash strike occurred in Philadelphia in 1944, further cementing the pattern of labor disputes over sanitation.

The legacy of sanitation strikes extends beyond Philadelphia, notably with the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike. This pivotal moment in American labor history involved a predominantly African American sanitation workforce demanding higher wages, basic safety procedures, and union recognition. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lent his powerful voice and support to the Memphis workers and their families as part of his Poor People’s Campaign, which aimed to organize working people across the nation to demand full economic and political rights. Dr. King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, intensified pressure on Memphis officials, leading to the settlement of the strike and the workers securing their demands on April 16. Following the Memphis strike, AFSCME began organizing public workers around the country, and throughout the 1970s, sanitation strikes and slowdowns continued in cities like New York, Atlanta, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C. These actions often resulted in modest wage boosts for predominantly African American workers, who gained significant community support. By the 1980s, such labor actions became less frequent. Philadelphia experienced another three-week sanitation strike in 1986, which resulted in some wage gains for the union but losses in healthcare benefits.

Key Philadelphia Sanitation Strikes

-

March 1937Brief work stoppage leads to initial discussions between city and union.

-

September 1938Weeklong strike with “street battles” leads to AFSCME recognition and demands met.

-

1944Another two-week trash strike occurs in the city.

-

1968 (Memphis)Memphis Sanitation Strike, supported by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leads to increased AFSCME organizing nationwide.

-

1986Three-week sanitation strike results in wage gains but losses in healthcare benefits.

-

July 2025Current DC 33 strike begins, marked by significant social media involvement.

Public Pulse and Social Media’s Power

Public support for the striking workers appears to be strong, a sentiment partly fueled by increased awareness of the critical roles essential workers play in society. Social media, including the narratives shared by individuals like former sanitation worker Terrill Haigler, known as “Ya Fav Trashman,” is significantly shaping public response and fostering support for the strikers. This digital engagement is unprecedented in Philadelphia labor disputes, allowing the union to disseminate its message directly and effectively.

The COVID-19 pandemic heightened public awareness of the indispensable role essential workers, many of whom are Black and brown individuals, play in keeping communities functioning. There is a growing perception that if the men and women who perform these vital jobs cannot afford basic needs, the system itself is flawed. This understanding has led to widespread empathy for the strikers. City Council members have also begun to weigh in on the DC 33 strike, with widespread support for the union members (inquirer.com). The collective voice of the community, amplified through social media, is putting considerable pressure on city leadership to address the workers’ demands.

Negotiations and the Path Forward

Negotiations between District Council 33 and Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration resumed on the second day of the strike (inquirer.com). The duration of the strike and the precise next steps in negotiations remain uncertain. The strike began on the first day after the expiration of DC 33’s previous contract, an aggressive tactic for a municipal union (inquirer.com). Union members and supporters marched around City Hall urging leaders to finish contract negotiations ahead of the strike deadline (WHYY.org).

Mayor Parker finds herself in a challenging position, as Philadelphia mayors traditionally negotiate four-year contracts with all four major municipal unions during their first year in office (inquirer.com). She has stated that the city has a $550 million labor reserve for negotiations, emphasizing her pro-labor stance while also maintaining a commitment to fiscal responsibility (inquirer.com). Mayor Parker has stated her administration is working to achieve a “fair and fiscally responsible contract,” indicating ongoing efforts to resolve the dispute (inquirer.com). The outcome of these negotiations will not only impact the lives of thousands of city workers and their families but also set a precedent for future labor relations in Philadelphia.

Key Stakeholders in the Philadelphia Strike

AFSCME District Council 33

Represents 9,000 blue-collar city workers. Demanding “life-changing raises” and better benefits. Led by President Greg Boulware, with 95% strike authorization.

Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s Administration

Negotiating new contracts in her first year. Aims for a “fair and fiscally responsible contract.” Has a $550 million labor reserve for negotiations.

Philadelphia Residents

Experiencing direct impact from service disruptions like “Parker piles” and closed facilities. Many show strong public support for the striking workers.

City Council Members

Many have expressed widespread support for the union members, reflecting the public sentiment and the importance of essential workers.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.