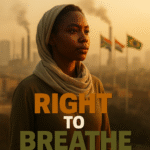

G20 Endorsees Clean Air Human Right: Policy Shift Linking Pollution and Justice

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Introduction: Clean Air as a Human Right and Global Justice

Across this week, the G20 communiqué marked a turning point by endorsing a first-of-its-kind cross-national framework treating clean air as a human right, a policy development shaped strongly by African delegations. Consequently, advocates and affected communities began to reframe air quality from an environmental technicality to a matter of justice. This shift ties air pollution to historical extraction, uneven industrial footprints, and colonial-era economic patterns that continue to shape who breathes clean air.

Moreover, this policy change moves international law and diplomacy toward recognizing pollution as a social and racial equity problem. African nations argued that emissions and industrial pollution generated largely by wealthy states have outsized health and economic impacts in the Global South. Thus, the G20 action connects air quality to reparative frameworks and global responsibility.

Detailed Analysis of the Current News Story: G20 Framework and African Leadership

At the G20 summit, the final communiqué contained language endorsing a cross-national approach to clean air that treats it as a universal right. While the communiqué is not a binding treaty, it creates political momentum and normative pressure on states and institutions to integrate air quality into human-rights and development policy. Furthermore, African delegations amplified the urgency, insisting the document reflect the disproportionate burdens their populations suffer due to transboundary pollution and imported industrial models (see Reuters for detailed coverage).

Consequently, the communiqué calls for stronger monitoring, financing for air-quality interventions, and cooperation on emissions reductions. In addition, it underscores links between pollution exposure, respiratory illness, and economic inequality. The African push centered two themes: first, historical responsibility for industrial emissions by long-industrialized states; and second, future resilience for African communities by financing cleaner infrastructure and remediating polluted sites (see Al Jazeera).

Historical Context: Colonial Extraction, Industrial Emissions, and Racialized Pollution

Historically, patterns of industrial growth and colonial extraction shaped who benefits from economic development and who receives the harms. During the colonial and early industrial eras, Western powers extracted minerals, crops, and labor from Africa to fuel factories and consumption in Europe and North America. Consequently, this arrangement generated emissions and environmental transformation concentrated near production sites, often without local consent or compensation. Over time, industrial pollutants traveled across borders, but the legal and moral frameworks did not hold exporting or consuming countries accountable.

In addition, post-colonial development strategies encouraged export-oriented industrialization, mining, and large-scale infrastructure investment. These strategies often replicated older inequalities, producing localized pollution hotspots near Black and marginalized communities. Environmental activists documented that pollution exposure correlates strongly with race and poverty, both within nations and across global regions. Therefore, the demand to recognize clean air as a human right emerges from a long history of exclusion from decision making and from the unequal distribution of industrial harms (for historical framing, see Brookings).

Key Terms Defined: Air Pollution, Environmental Justice, and Reparative Responsibility

Below are concise definitions intended to clarify the terms used in the story and infographic. These definitions will help readers understand policy language and how it affects Black and African diaspora communities.

Air Pollution

Particles and gases in the atmosphere that harm health and ecosystems, including PM2.5, NOx, SO2, and ozone.

Environmental Justice

The principle that all people should have equal protection from environmental harms and equal access to decision-making about their environment.

Reparative Responsibility

The concept that states or corporations that historically benefited from polluting activities owe remediation, financing, or policy changes to harmed communities.

Transboundary Pollution

Pollution that crosses national borders, requiring international cooperation for monitoring and mitigation.

Why This Matters Today: Health, Equity, and Political Power

First, air pollution is a major public health crisis. It contributes to respiratory illness, cardiovascular disease, and reduced life expectancy. African and Black diaspora communities both within and outside the continent often suffer elevated exposure because industrial facilities, mining, and heavy transport infrastructure disproportionately sit near marginalized neighborhoods. Therefore, when a major international forum like the G20 endorses clean air as a human right, it creates leverage to direct finance and technology to those communities that need it most (see WHO on health impacts: WHO).

Second, this development reshapes accountability. Rather than treating pollution as a localized technical issue, the rights frame demands cross-border responsibility for emissions and historical patterns of extraction. Consequently, that framing supports calls for financial transfers, cleaner industrial investment, and stricter export controls on hazardous technologies. This is critical for African economies seeking to develop while avoiding the health costs that accompanied industrial growth in the Global North.

Policy Implications: Financing, Standards, and Community Power

Once framed as a right, clean air requires enforcement pathways and finance. Thus, multilateral banks and climate funds may face growing pressure to prioritize air-quality projects. In addition, G20 backing can accelerate monitoring standards and emissions reporting. Consequently, local communities will gain tools to demand remediation and protection. For the Black and diaspora communities affected by pollution, these tools can strengthen legal claims and political leverage within national systems (see reporting on finance commitments at the G20: Financial Times).

Moreover, this is a political win for African diplomacy. It shows capacity to shape global agendas and reframes climate and environmental policy as matters of justice rather than only emissions accounting. The implication is that future climate and development negotiations will contain stronger language about historical responsibilities and compensation for harm.

Conclusion: Clean Air Rights as a Step Toward Global Environmental Justice

In summary, the G20 endorsement of a framework treating clean air as a human right is both symbolic and practical. It signals a shift toward connecting environmental protection with racial and historical justice. For African and diaspora communities, it opens pathways for funding, accountability, and stronger legal arguments for remediation. Consequently, this development matters because it reframes who is responsible for pollution harms and who should pay for the remedies.

As this framework moves from communiqué language toward implementation, attention must remain on monitoring, financing, and community participation. Likewise, activists and policymakers should insist that commitments translate into measurable reductions in exposure for the most harmed communities. Thus, the clean air rights frame must lead to cleaner neighborhoods, healthier children, and greater political equity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.