The Benjamin Jackson Case and America’s Ongoing Struggle with Police Accountability

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Night That Changed Everything: November 2022

On November 6, 2022, around 8 PM, Benjamin Jackson stepped out of an SUV at the intersection of Broadway and East 18th Street in Paterson, New Jersey, wearing a black fanny pack. The 35-year-old African American man was still recovering from recent brain surgery, with stitches in his head and a documented seizure condition. What happened next would lead to a federal lawsuit that exposes deep-seated problems within one of New Jersey’s most troubled police departments and raises urgent questions about police accountability in America (Atlanta Black Star).

Four plainclothes Paterson Police Department officers in an unmarked vehicle noticed Jackson. Officer Muhammed Dombayci later reported that Jackson appeared “startled,” widened his eyes, and touched his fanny pack in a manner the officers associated with armed individuals concealing weapons. These observations became the justification for what would follow (NJ.com). However, body camera footage allegedly tells a different story, one where Jackson complied with police commands, repeatedly asked for a supervisor fifteen times, and informed officers about his vulnerable medical condition before being subjected to what he describes as a brutal assault (Brown Watch).

Jackson’s lawsuit alleges that despite his cooperation and medical warnings, Officer Wisam Salameh violently threw him to the ground, then kicked him, punched him in the face, chest, and stomach, and slammed his face into the pavement, aggravating his brain surgery wound. In addition, after handcuffing Jackson, Salameh allegedly grabbed his scrotum and said, “That is for free, bro, do not even worry about it.” At the same time, other officers stood by laughing instead of intervening (NorthJersey.com). These allegations, if proven true, represent not just excessive force but also sexual assault committed under the color of law against a medically vulnerable individual in handcuffs.

The Medical Emergency Police Officers Mocked

After the alleged assault, Jackson was placed in a police vehicle. Shortly after the car left the scene, he suffered a seizure, a predictable consequence given his recent brain surgery and the trauma he had just experienced. Officer Malek Assaf, who was driving, initially believed Jackson was “deliberately banging his head around in the back seat” and only after some time agreed to pull over and call an ambulance (Atlanta Black Star).

When emergency medical personnel arrived, Jackson told them about the seizure and that one of the officers had grabbed his testicles. The officers responded by mocking him, stating they “did not see him foaming at the mouth” and therefore doubted he had experienced a seizure. This dismissive attitude toward a medical emergency constitutes what legal experts call denial of medical care, a serious civil rights violation (NJ.com). Jackson was eventually taken to a hospital, where medical professionals treated him for pain in his scrotum and administered medication for his seizures. Doctors later diagnosed him with an injury to his left testicle that required surgical treatment and warned that the severity of the injury could cause infertility (BlackNews.com).

This pattern of ignoring medical needs is particularly concerning for Black individuals in police custody. Research shows that Black people experience police misconduct at a rate six times higher than white people during police encounters. In 2022, four percent of Black people experienced misconduct in their most recent police contact compared to just 0.7 percent of white people (Prison Policy Initiative). The denial of medical care represents one manifestation of this broader pattern of differential treatment.

Paterson’s Long Shadow: A Department Under State Control

The Benjamin Jackson case did not occur in isolation. It happened within the context of the Paterson Police Department, an agency with such a troubled history that the New Jersey Attorney General took the unprecedented step of seizing complete control of the department in March 2023 (NJ Office of the Attorney General). This supersession followed the fatal police shooting of Najee Seabrooks, a 31-year-old anti-violence advocate experiencing a mental health crisis, but it was the culmination of years of systemic problems (ABHM).

Between 2018 and 2020, Black residents of Paterson, who comprise only about 25 percent of the city’s population, were subjected to 57 percent of the police department’s more than 600 uses of force, according to an investigation by the Police Executive Research Forum (ABHM). This stark disparity mirrors national trends where Black Americans face police violence at rates far exceeding their population share. Moreover, the department has faced criminal charges against a dozen officers, millions in legal settlements, deaths in police custody, and an ongoing FBI corruption investigation (New Jersey Institute for Social Justice).

Attorney General Matthew Platkin criticized the “revolving door” of police leadership in Paterson, which has resulted in dysfunction within police ranks and a lack of trust in local law enforcement. He appointed Isa Abbassi, a 25-year veteran of the New York Police Department and former Chief of Strategic Initiatives, to oversee the department’s operations (NJ Office of the Attorney General). In July 2025, the New Jersey Supreme Court unanimously upheld the state takeover, ruling that the legislature had authorized this extraordinary intervention to address the department’s pervasive problems (New York Times).

The Criminal Conviction That Complicates Justice

Despite the allegations of misconduct, Jackson was convicted in February 2024 of unlawful possession of a handgun related to the November 6, 2022 incident. According to police reports, officers found a loaded handgun with five bullets in his fanny pack during the search (NorthJersey.com). He received a sentence of up to 42 months in prison and was incarcerated at Bayside State Prison in South New Jersey until May 8, 2024, when he was paroled (Atlanta Black Star).

The criminal conviction adds complexity to Jackson’s civil rights case. Defense attorneys often use criminal convictions to undermine the credibility of plaintiffs in civil lawsuits. However, legal experts emphasize that police misconduct and criminal culpability are separate issues. Even individuals who have committed crimes retain constitutional rights to be free from excessive force, sexual assault, and denial of medical care while in police custody (Equal Justice Initiative). The existence of contraband does not justify violent or sexually abusive treatment of a handcuffed individual who has already been subdued and is complying with commands.

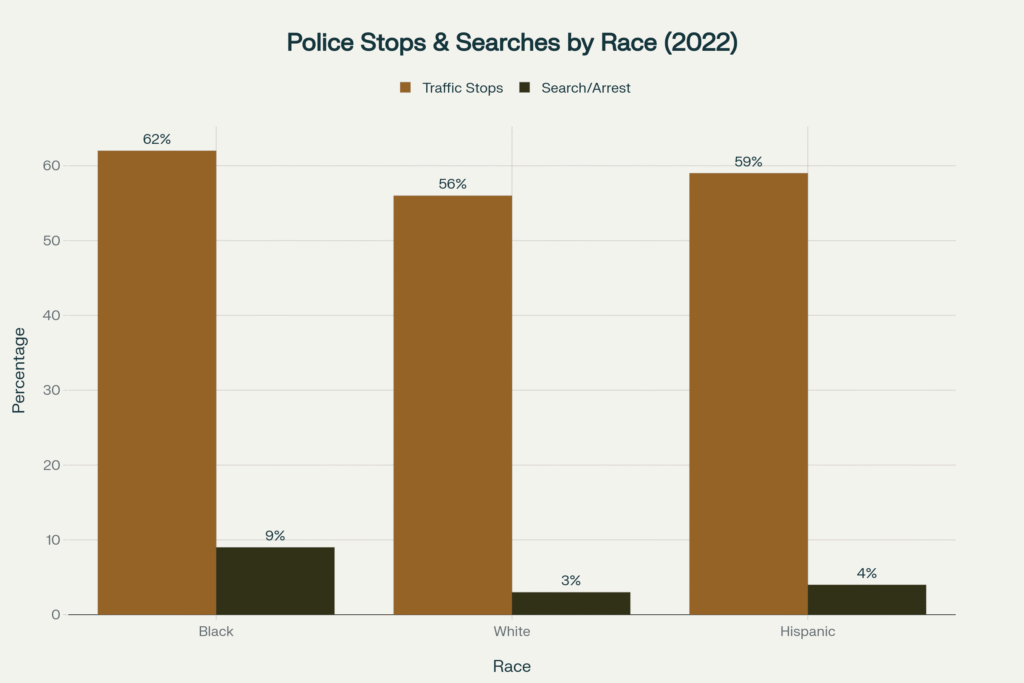

This case highlights a troubling pattern in policing where officers use the discovery of contraband to retroactively justify questionable stops and violent treatment. Research from 2018 showed that police searched Black and Latinx drivers 1.7 and 2.6 times as often as white drivers during traffic stops, yet were less likely to find illegal drugs, weapons, or contraband in their vehicles (The Sentencing Project). These contraband hit rate disparities have been documented in jurisdictions across the country, including in New Jersey.

Federal Court Ruling: Partial Victory, Ongoing Battle

On September 22, 2025, U.S. District Judge Jamel K. Semper issued a ruling that represents both progress and limitation in Jackson’s quest for accountability. The judge ruled that Jackson’s claims of excessive force and assault and battery against four officers who were plausibly identified in the complaint as having physically abused him can move forward. These officers are Wisam Salameh, Muhammed Dombayci, John Rikowich, and Corey Davis (Atlanta Black Star).

Judge Semper also allowed Jackson’s claim that Officers Malek Assaf and Domenic DiCarlo ignored his pleas for medical help after he suffered a seizure in the back of the patrol car. In addition, a separate claim accusing the City of Paterson of failing to properly train and supervise its officers was permitted to proceed (NJ.com). These claims represent the core of Jackson’s case and could provide a pathway to both individual accountability for the officers involved and systemic reform within the department.

However, Judge Semper dismissed many of Jackson’s other claims. The allegations of false imprisonment against all defendants were dismissed because they relied on an “improper group pleading,” meaning the court could not determine which specific defendants were responsible for Jackson’s detention following his arrest. The judge also dismissed Jackson’s claims of emotional distress and negligence against the officers and the city for lack of specificity. Most significantly, Jackson’s claim of racial discrimination was dismissed because he offered “only a few conclusory allegations” that he was stopped, searched, and assaulted due to his race, without substantiating that claim with sufficient evidence (Court Documents).

Historical Context: New Jersey’s Troubled Policing Legacy

The Jackson case must be understood within the broader context of New Jersey’s long and troubled history of racial profiling and police misconduct. In 1996, Superior Court Judge Robert E. Francis handed down a landmark decision in State v. Pedro Soto, finding for the first time that the New Jersey State Police maintained a de facto policy of targeting minority motorists solely based on race (New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus Report). The court condemned this practice as a clear violation of the Fourteenth Amendment right to equal protection.

Statistical evidence presented in that case documented that Black motorists traveling on the New Jersey Turnpike between exits 1 and 3 accounted for approximately 15 percent of actual traffic violations. However, while accounting for only 15 percent of violations, Black drivers comprised 46 percent of stops and 73 percent of arrests. Between exits 1 and 7A, Black motorists accounted for approximately 35 percent of stops and 73 percent of arrests (New Jersey Legislative Black and Latino Caucus Report). These disparities revealed a pattern of unconstitutional racial profiling that continued for years despite judicial findings and reform efforts.

In 1999, following a federal investigation, the New Jersey State Police consented to a federal decree regarding racist policing practices, and the state’s attorney general publicly acknowledged the reality of racial profiling for the first time. The decree, originally intended to last five years, remained in effect until 2009 (The Conversation). Despite these interventions, racial disparities in policing persist across New Jersey and the nation. The Jackson case represents a continuation of this legacy, where Black individuals face higher rates of police-initiated contact, searches, arrests, use of force, and misconduct compared to their white counterparts.

National Crisis: Rising Police Violence Despite Reform Efforts

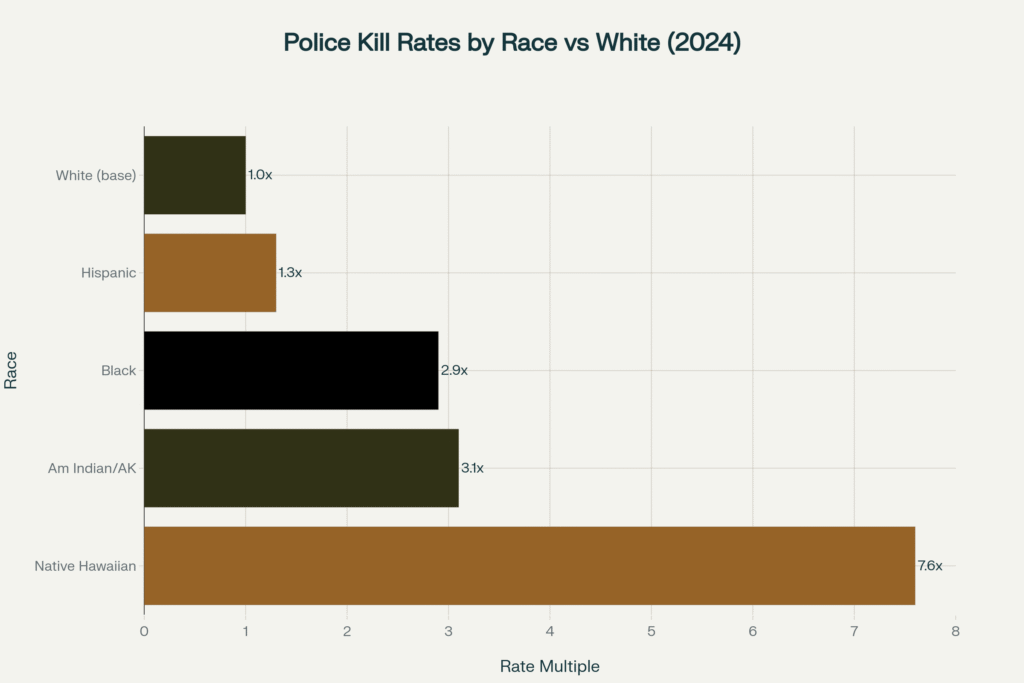

The year 2024 marked the deadliest year for police violence on record, with 1,365 people killed by law enforcement officers according to Mapping Police Violence. This represents an increase despite a national decline in homicides and violent crime. On average, law enforcement killed someone every 6.44 hours, and there were only 10 days in 2024 when U.S. law enforcement did not kill someone (Campaign Zero).

Racial disparities in police killings remain stark and persistent. Black people were 2.9 times more likely than white people to be killed by police in 2024. Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders faced the highest racial disparity, being 7.6 times more likely to be killed by police than white people. American Indian and Alaska Native individuals were 3.1 times more likely to be killed, and Hispanic people were 1.3 times more likely (Campaign Zero). These statistics demonstrate that police violence disproportionately impacts communities of color, with Black, Brown, and Indigenous people bearing the brunt of lethal force despite comprising smaller percentages of the overall population.

Beyond fatal encounters, non-lethal police violence also exhibits profound racial disparities. In 2022, Black people were over three times as likely as white people to experience the threat or use of force during police encounters, including handcuffing, pushing, grabbing, hitting, kicking, or having a weapon used against them (Prison Policy Initiative). Black Americans were also 9.3 times as likely as white Americans to be homicide victims in 2020, and since homicide is largely an intra-racial crime, these figures correspond to higher rates of violence within communities of color, which scholars attribute to spatially concentrated urban poverty resulting from longstanding segregation, discrimination, and disinvestment (The Sentencing Project).

The Qualified Immunity Shield: Barrier to Justice

One of the most significant obstacles Jackson faces in his pursuit of justice is the legal doctrine of qualified immunity. This court-created rule limits victims of police violence and misconduct from holding officers accountable when they violate constitutional rights. Under this doctrine, a police officer cannot be put on trial for unlawful conduct unless the person suing proves that the evidence shows the conduct was unlawful and that the officers should have known they were violating “clearly established” law because a prior court case had already deemed similar police actions illegal (Equal Justice Initiative).

The Supreme Court developed qualified immunity in 1967 through its interpretation of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, which Congress passed to help protect formerly enslaved Black people from rampant racial violence during Reconstruction. In 1982, the Court dramatically expanded the doctrine in Harlow v. Fitzgerald to protect public officials from even malicious conduct as long as the conduct did not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights (Equal Justice Initiative). This expansion has created what Justice Sonia Sotomayor described as “an absolute shield” against accountability for police officers accused of using excessive force.

Courts often require a nearly identical prior case to establish “clearly established law,” leading to absurd results. For example, in one case, officers received immunity for releasing a police dog on a suspect who had surrendered by sitting with his hands raised because prior precedent involved a suspect who surrendered by lying down. In another case, officers who stole hundreds of thousands of dollars while executing a search warrant received immunity because the court could find no prior case addressing theft during searches (New Mexico General Services). These rulings demonstrate how qualified immunity effectively prevents accountability even for egregious misconduct.

Sexual Violence Under Color of Law: A Hidden Epidemic

The sexual assault allegations in Jackson’s case represent a particularly disturbing form of police misconduct that often goes unreported and unpunished. Police officers who sexually assault individuals in their custody exploit an extreme power imbalance where victims are physically restrained, isolated from witnesses or help, and face the threat of additional charges or violence if they resist or report the abuse (BBC News).

In 2017, two New York Police Department detectives, Eddie Martins and Richard Hall, were charged with raping an 18-year-old woman in the back of their police van after arresting her for marijuana possession. The officers admitted to having sex with the handcuffed teenager but claimed it was consensual. The rape charges were eventually dropped due to credibility concerns, and the officers pleaded guilty to official misconduct, receiving only five years of probation and no prison time (BBC News). This case exposed a legal loophole that previously allowed New York police officers to have sex with people in custody as long as it was deemed consensual, a provision that was subsequently changed but could not be applied retroactively.

More recently, in April 2025, Atlantic City police officer Joshua Munyon was charged with sexual assault and official misconduct after allegedly driving a handcuffed victim to a parking lot and assaulting her while she was still in restraints. Authorities say Munyon denied ever arresting the victim after the assault was reported (6ABC Philadelphia). These cases reveal a pattern where officers exploit their authority and the vulnerability of handcuffed individuals to commit sexual violence, confident that the power differential and legal protections afforded to police will shield them from consequences.

Reform Efforts After George Floyd: Progress and Setbacks

The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in May 2020 sparked the largest racial justice demonstrations in the United States since the civil rights movement of the 1960s. More than 15 million people participated in protests demanding police reform and an end to police brutality (EBSCO Research Starters). These protests led to proposed legislation at federal, state, and local levels aimed at increasing police accountability and reducing violence.

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, introduced by Democrats in Congress in June 2020, sought to make it easier for the federal government to prosecute cases of police misconduct, eliminate qualified immunity, ban chokeholds and no-knock warrants, and require the use of deadly force only as a last resort. The act passed in the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives but failed to move forward in the Senate (EBSCO Research Starters). After being reintroduced in March 2021, it again passed the House but the Senate failed to reach an agreement in September of that year, effectively ending efforts at comprehensive federal police reform.

Despite the failure of federal legislation, at least 30 states and Washington, DC enacted one or more statewide legislative policing reforms between 2020 and 2024. These reforms included banning chokeholds, knee restraints, and no-knock warrants; requiring the use of body and dashboard cameras; restricting police access to military equipment; and requiring training on racial profiling (Brennan Center). However, the effectiveness of these reforms remains limited. The number of people killed by police has risen every year since George Floyd’s murder, reaching record levels in 2024 despite these reform efforts (New York Times).

Officers are charged with a crime in only about three percent of all police killings each year, and convictions are even rarer (Police Violence Report). This lack of accountability perpetuates a culture where officers can use excessive force with little fear of consequences. Research shows that Black prosecutors, especially Black women who represent only one percent of the nation’s elected prosecutors, are disproportionately responsible for charging and convicting officers involved in killings, comprising eight percent of prosecutors who charged officers and 16 percent who charged officers in two or more deadly force incidents between 2013 and 2024 (Police Violence Report).

Why This Matters Today: The Struggle for Basic Human Rights

The Benjamin Jackson case matters because it encapsulates the daily reality faced by Black Americans in their interactions with law enforcement. Jackson’s allegations describe a cascade of constitutional violations: a questionable stop based on minimal suspicion, excessive force used against a medically vulnerable individual who was complying with commands, sexual assault committed while the victim was handcuffed and helpless, denial of urgently needed medical care, and mockery by officers who found entertainment in his suffering. Each element represents a betrayal of the fundamental promise that all people will be treated with dignity and that those who wield state power will be held accountable when they abuse it.

This case also highlights the intersecting vulnerabilities that can make individuals targets for police violence. Jackson was Black, which research shows dramatically increases the likelihood of police-initiated contact, searches, force, and misconduct. He was recovering from brain surgery, making him physically vulnerable and dependent on officers to respect his medical needs. He was in a high-crime neighborhood, where over-policing and aggressive tactics are often justified as necessary for public safety despite evidence that such approaches erode community trust and fail to address root causes of crime (The Sentencing Project).

The fact that the Paterson Police Department’s problems were so severe that the state Attorney General felt compelled to seize control demonstrates the depth of the crisis. The department’s pattern of misconduct, including criminal charges against a dozen officers, millions in settlements, and pervasive use of excessive force against Black residents, created an environment where officers could allegedly commit acts like those described in Jackson’s lawsuit without fear of immediate consequences (New Jersey Institute for Social Justice).

As Jackson’s case proceeds through federal court, it represents more than one man’s quest for justice. It serves as a test of whether legal remedies can provide meaningful accountability for police misconduct despite the barriers created by qualified immunity and the inherent power imbalances between police and citizens. The outcome will send a message to both victims of police violence and officers who may consider abusing their authority. Will courts enforce constitutional protections for vulnerable individuals in police custody, or will procedural hurdles and legal doctrines continue to shield officers from consequences for egregious conduct? The answer to that question will shape not only Jackson’s life but also the broader struggle for police accountability and racial justice in America.

The case reminds us that police reform cannot be achieved through legislation alone. It requires cultural transformation within law enforcement agencies, robust accountability mechanisms that actually result in discipline and prosecution when misconduct occurs, and a fundamental rethinking of how we approach public safety in communities that have been historically over-policed and under-resourced. Until these changes occur, cases like Benjamin Jackson’s will continue to emerge, documenting the human cost of a system that too often prioritizes the protection of officers over the constitutional rights of the people they are sworn to serve.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.