When Video Proves Police Lied: Jeffrey Sutton Case Exposes Deep Roots of Anti-Black Policing

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Nightmare Captured on Camera

Jeffrey Sutton thought he was going to die. It was November 2020 in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Unmarked police cars boxed in his Mercedes-Benz (103.7 The Beat). Officers in plain clothes jumped out. Sutton had no idea they were police. He panicked and reversed.

Captain Gary Peters pointed a gun at his head. The officer threatened to blow his head off (BlackNews.com). Sutton turned off his engine. He raised his hands. He begged for his life, explaining he was unarmed. Two officers holstered their weapons. However, Peters remained hostile.

Fearing for his safety, Sutton tried to back away. He accidentally hit another car. At that moment, Peters and another officer opened fire. They struck him multiple times, badly injuring his arm (103.7 The Beat).

Police claimed Sutton tried to ram them with his car. They charged him with four counts of aggravated assault on law enforcement officers. Sutton spent more than three years in jail. Then video footage emerged. News cameras and police body cameras told a different story. Sutton was driving away from officers, not toward them (BlackNews.com).

Most charges were dismissed once the videos surfaced. Sutton pleaded guilty only to eluding police (News 12 New Jersey). Now 42, he continues to live with nerve damage and emotional trauma. He filed a lawsuit accusing the officers of excessive force, false reporting, and racial bias (103.7 The Beat).

The officer who shot him? Gary Peters was promoted to Deputy Chief of Police in 2023 (Bloomfield Police Department).

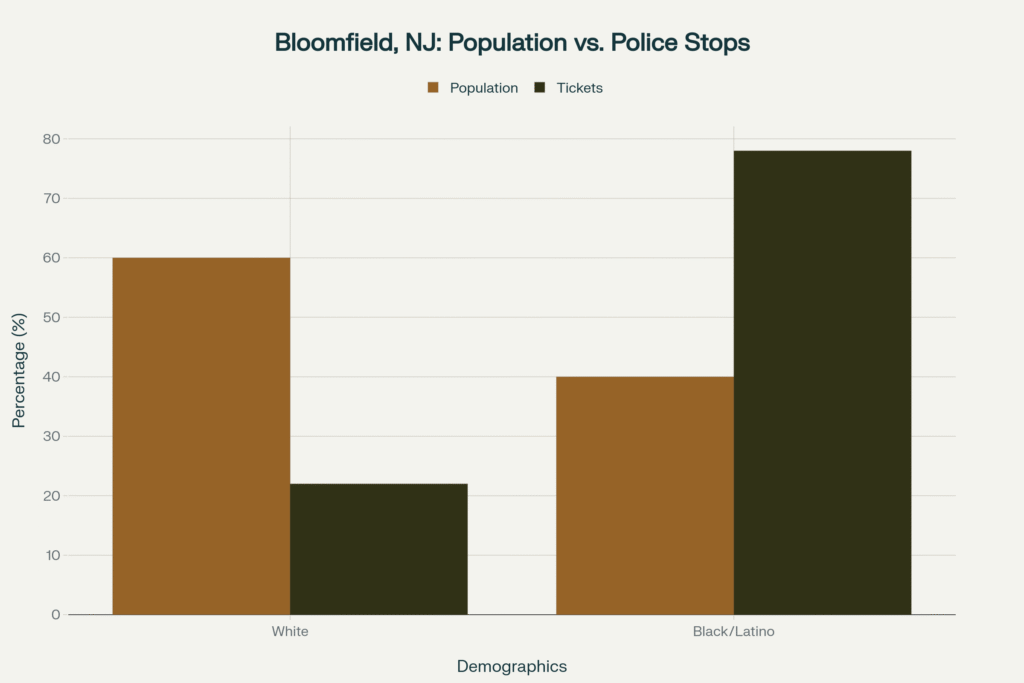

Bloomfield’s Pattern of Targeting Black Communities

Jeffrey Sutton’s case is not isolated. Bloomfield Police Department has a documented history of targeting Black and Latino residents. A Seton Hall University study revealed disturbing patterns. While Bloomfield’s population is 60 percent white, Black and Latino residents make up 78 percent of court appearances in Bloomfield Municipal Court (ACLU-NJ).

Nearly 84 percent of tickets issued in Bloomfield occur in the geographic lower third of the township. This area borders Newark and East Orange, communities predominantly made up of people of color. The study indicates that Black and Latino residents are dramatically over-policed in Bloomfield. Moreover, they paid more than $1 million to Bloomfield Municipal Court between September 2014 and August 2015 (ACLU-NJ).

Researchers described Bloomfield Police policing patterns as a de facto border patrol. By plotting out ticket incidence and frequency, one can see what essentially amounts to a wall of police erected against the Newark and East Orange border areas and their predominantly Black and Latino residents (Seton Hall Law Center for Policy & Research).

This pattern of police citations resulted in a dramatic subsidy of Bloomfield by Black and Latino residents. In large part, this came from residents of Newark and East Orange. For each individual charged, the average cost was $137 plus surcharges. That suggests that for Black and Latino people as a group, 7,566 tickets totaled more than $1 million paid to Bloomfield Municipal Court (Seton Hall Law Center for Policy & Research).

When the System Protects Those Who Abuse Power

The Sutton case reveals how easily police can lie and face no consequences. Captain Peters and other officers claimed on official reports that Sutton intentionally drove into not one, not two, but four police officers, causing injuries to all of them. Video footage proved this was entirely false (News 12 New Jersey).

Despite the false reports, no officers faced criminal charges. Peters not only kept his job but received a promotion. This lack of accountability is not unique to Bloomfield. Police officers nationwide continue to use excessive force with little fear of consequences.

Qualified immunity shields police officers from civil liability unless they violate “clearly established” law. In practice, this means unless there exists a prior court case with nearly identical facts, officers can violate constitutional rights without being held personally responsible. The doctrine has been used to protect officers in cases of fatal shootings, police brutality, theft, and sexual misconduct (Equal Justice Initiative).

Body cameras were supposed to solve this problem. However, officers still misuse them. A BBC investigation uncovered more than 150 reports of camera misuse by police forces. Officers switched off cameras when force was used, deleted footage, and shared videos inappropriately (BBC News).

In Sutton’s case, the video evidence saved him from spending decades in prison on false charges. Nevertheless, he still spent three years behind bars before the truth emerged. He still suffers from nerve damage that prevents him from working in his field as an HVAC technician (The Jersey Vindicator).

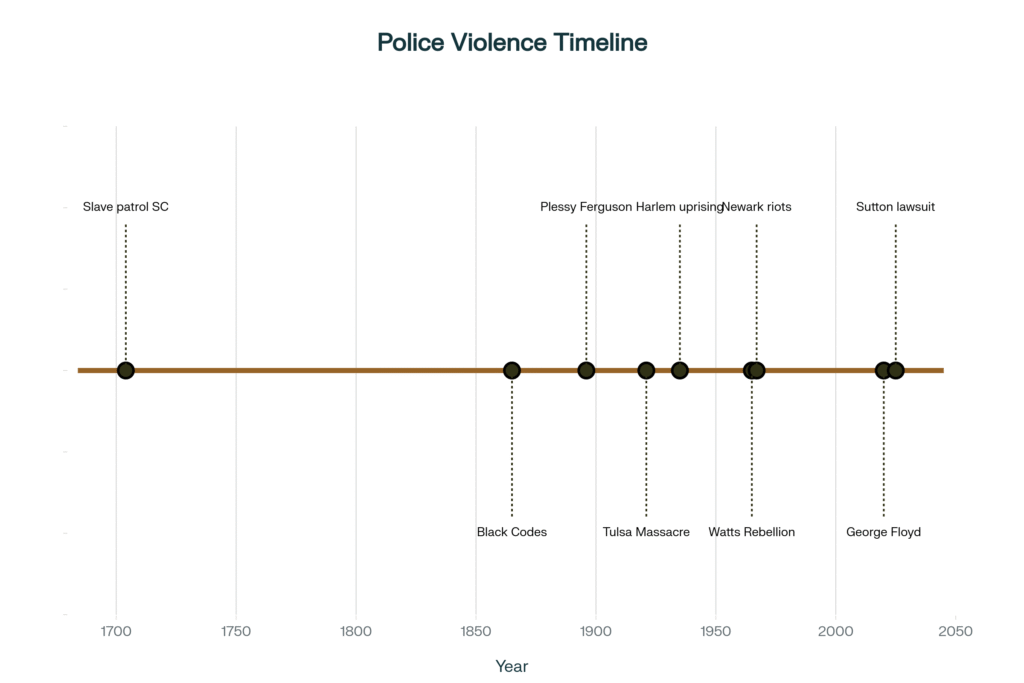

Slave Patrols: The Violent Origins of American Policing

To understand why Jeffrey Sutton was shot, why police lied, and why those officers faced no consequences, we must look back more than 300 years. The roots of American policing are found in slavery and the violent control of Black bodies.

The first slave patrol was created in South Carolina in 1704. These patrols consisted of white citizens who regulated the activity of enslaved people. They had three main functions: chasing down and returning runaway slaves, preventing and subduing slave revolts, and policing communities through what would now be called crime suppression tactics (National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund).

Slave patrols had the authority to perform raids and searches without cause or warrant. They looked for contraband like pencil and paper, which indicated illegal education, or Bibles. All of this was to maintain civil order, which meant keeping enslaved people terrorized and controlled (Reddit AskHistorians).

As Harvard professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad explains, the surveillance, the deputization of all white men to be slave patrollers, and the power to dispense corporal punishment on the scene are all baked in from the very beginning (Harvard Gazette).

When the Civil War ended slavery in 1865, former Confederate states quickly found a workaround. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery except as punishment for crime. Southern states passed Black Codes, which criminalized every form of Black freedom and mobility except the right to work for a white man on a white man’s terms (Harvard Gazette).

Black Codes required all Black people to sign annual labor contracts with white employers. If they did not, or if they did not fulfill the terms of these contracts, they would be deemed vagrants and fined or imprisoned. These laws provided white citizens the authority to act as police officers for the detection of offenses and the apprehension of offenders (EBSCO).

This environment of fear meant that Black people were falsely charged and often punished because of the vague and broad language of the Codes. The heightened racial tensions conveyed by white Southerners resulted in Black people finding themselves in a situation that arguably rivaled slavery (EBSCO).

Jim Crow Policing: Making Racism the Law

When Black Codes were struck down during Reconstruction, the South simply found new ways to enforce white supremacy through law. Jim Crow laws, enacted from the mid-1880s through 1965, made segregation of Black and white people official. The police job was to enforce those laws and norms (Rutgers University Press).

Police were the foot soldiers in the battle to maintain Black subordination in cities across the South. Brandon Jett, author of Race, Crime, and Policing in the Jim Crow South, describes how Black communities were simultaneously under-policed and over-policed. There were high rates of Black arrests for nonviolent offenses such as vagrancy. Simultaneously, law enforcement officers typically showed little concern for crimes involving Black victims, including homicide (Rutgers University Press).

Jim Crow was not just enforced by traditional police. It was enforced by individuals who had no legal authority but were nevertheless recognized as proper enforcers of Jim Crow norms and rules. White bus drivers, teachers, librarians, and many others monitored the Black public for violations of Jim Crow laws (Northeastern University).

The violation of segregated, racist norms often meant violence against Black people. The machine of Jim Crow, sometimes legislated and sometimes condoned through inaction, reinforced the idea that any white person could commit racially motivated violence with impunity (Northeastern University).

This pattern continued through the civil rights movement. In 1960, Attorney Loren Miller testified before the United States Commission on Civil Rights that 80 complaints of police brutality were filed in Los Angeles in 1958. Only two were determined to be justified. There were 21 complaints of civil rights violations. None were viewed as justified (African American Intellectual History Society).

The Illinois Crime Survey of 1929 found that although Black people made up just five percent of the Chicago area’s population, they constituted 30 percent of the victims of police killings (Smithsonian Magazine).

When Police Violence Sparked Mass Uprisings

Throughout the 20th century, police brutality against Black Americans sparked major uprisings across the country. These events reveal a pattern: police violence leads to community response, which is then met with more police violence.

In July 1967, Newark erupted after two white police officers beat and arrested Black cab driver John William Smith. Residents saw an incapacitated Smith being dragged into the precinct. Rumors spread that he had been beaten to death in police custody. A large crowd formed outside the precinct (Wikipedia).

Over six days, 26 people died. Most were killed by police and National Guard troops. Police and National Guard members fired indiscriminately into buildings. They claimed to be hunting for snipers but often killed innocent people. Three men were shot to death by police who later said they were hunting for a sniper on upper floors (Wikipedia).

Photographer Bud Lee captured images of a police officer gunning down 24-year-old William Furr, who had stolen a six-pack of beer from a ransacked liquor store. Pellets from the shotgun blast also struck 12-year-old Joe Bass Jr., who was bleeding on the ground. Bass survived but his image became the cover of Life magazine (Wikipedia).

Two years earlier, in August 1965, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles burned for six days after California Highway Patrol officers pulled over Marquette Frye for suspected drunk driving. When officers tried to arrest him, a physical confrontation ensued. Frye was struck in the face with a baton. A crowd gathered and rumors spread that police had kicked a pregnant woman. The resulting uprising left 34 people dead and caused more than $40 million in property damage (Wikipedia).

Police Chief William Parker described the uprising as an insurrection akin to the Viet Cong. Nearly 14,000 members of the California Army National Guard helped suppress the disturbance (Wikipedia).

The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 stands as one of the most horrific examples of police participation in racial violence. When Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black man, was arrested for allegedly assaulting a white woman, a white mob gathered at the courthouse demanding a lynching. Black men from the Greenwood neighborhood came to protect Rowland (Department of Justice).

Local police deputized hundreds of white residents. Many had been advocating for a lynching and had been drinking. Law enforcement officers helped organize these special deputies into martial forces that ravaged Greenwood. Over several hours, they looted, burned, and destroyed 35 city blocks. Some Black residents were shot or otherwise assaulted. Many were arrested or detained (Department of Justice).

A 2025 Department of Justice report concluded that law enforcement actively participated in the destruction, disarming Black residents, confiscating their weapons, and detaining many in makeshift camps under armed guard. There are allegations that some members of law enforcement participated in arsons and murders (Department of Justice).

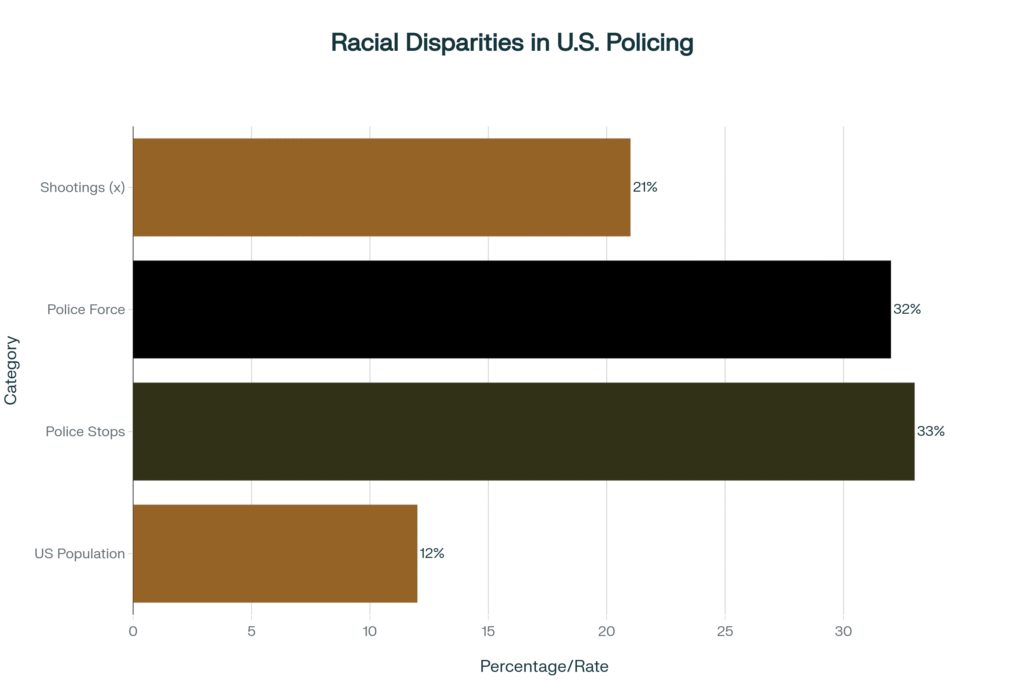

Modern Policing: Old Patterns in New Forms

The patterns established during slavery and Jim Crow continue today. Black Americans make up about 12 percent of the United States population. However, they represent 33 percent of all people who experience police stops and 32 percent of those who experience threat or use of force by police (Prison Policy Initiative).

Black people are more than twice as likely to be searched or arrested during a traffic stop as white people. Four percent of Black people experienced misconduct in their most recent police contact, which is six times the proportion of white people who experienced misconduct (Prison Policy Initiative).

In their most recent police encounters, Black people were over three times as likely as white people to experience the threat or use of force. This includes handcuffing, pushing, grabbing, hitting, kicking, and having a weapon used against them. Since 2020, the proportion of white and Hispanic people experiencing the threat or use of force has decreased. Meanwhile, the proportion of Black people experiencing threats or nonfatal use of force has increased (Prison Policy Initiative).

Police officers have fatally shot at least 135 unarmed Black men and women nationwide since 2015. At least 75 percent of the officers were white. Nearly 60 percent of the shootings occurred in the South (Equal Justice Initiative).

An NPR investigation found that at least six of the officers who shot and killed unarmed Black people were hired as police officers despite serious red flags in their backgrounds. These included drug use, domestic violence, and being fired from another police department. Several officers kept their jobs after they were convicted of crimes including battery and obstructing justice (Equal Justice Initiative).

The Economics of Racial Profiling

The Seton Hall study of Bloomfield reveals something often overlooked in discussions of police brutality: the financial incentive. Black and Latino residents paid more than $1 million to Bloomfield Municipal Court between September 2014 and August 2015. From the residents of East Orange and Newark, who received 29 percent of tickets, Bloomfield Municipal Court received nearly $400,000 (Seton Hall Law Center for Policy & Research).

The annual budget of the Court is about $500,000. This suggests a substantial profit from this pattern of law enforcement. Most of it comes from nonresidents of Bloomfield. It is heavily weighted on the backs of Black and Latino people as a group. Not coincidentally, the Municipal Court’s budgeted salaries were projected to more than double in 2015, from $350,600 in 2014 to an estimated $760,794 in 2015 (Seton Hall Law Center for Policy & Research).

This pattern exists across the country. Ferguson, Missouri, derived nearly a quarter of its budget from fines and fees. A Department of Justice investigation found that Ferguson’s law enforcement practices were shaped by the city’s focus on revenue rather than public safety. Black people made up 67 percent of Ferguson’s population but 85 percent of vehicle stops, 90 percent of citations, and 93 percent of arrests (Department of Justice Ferguson Report).

Systemic Barriers to Police Accountability

Jeffrey Sutton’s case highlights the multiple barriers to holding police accountable. First, police filed false reports claiming he tried to run them over. These reports could have sent him to prison for decades if video evidence had not emerged. Second, despite the false reports being exposed, no officers faced charges. Third, the officer who shot him was promoted.

Qualified immunity plays a major role in this lack of accountability. The doctrine was created by the Supreme Court in 1967, ostensibly to protect government employees from frivolous lawsuits. Instead, it has become an absolute shield against accountability for police officers accused of using excessive force (Equal Justice Initiative).

Even if a person can demonstrate that a police officer acted unlawfully, the officer will not be liable unless there exists a prior court case with nearly identical facts. Courts often require a nearly identical case to use as clearly established precedent. For example, one court held that precedent showing it was unconstitutional to release a police dog on a suspect who surrendered by lying down did not clearly establish that it was unconstitutional to release a police dog on a suspect who surrendered by sitting with arms raised (Equal Justice Initiative).

Body cameras were supposed to provide accountability. However, they often fail to deliver on that promise. Police departments withhold footage. Officers turn cameras off during critical moments. Footage gets deleted or lost. In some cases, departments refuse to release footage for years, arguing it could cause civil unrest (ProPublica).

In Memphis, officers in a street-crimes unit regularly abused residents. They wore body cameras but faced no consequences until the case of Tyre Nichols, who was beaten to death in January 2023, attracted national attention. The footage showed that some officers took their cameras off. Others knew they were being recorded and pummeled Nichols anyway (ProPublica).

The Psychological Toll on Black Communities

The impact of police violence extends far beyond those directly shot or beaten. It creates a pervasive sense of fear and trauma throughout Black communities. Jeffrey Sutton describes the psychological torment of having a gun pointed at his head while begging for his life. He explains how Captain Peters threatened to blow his head off if he kept fidgeting or reached for the door handle. Sutton did not know what to do (103.7 The Beat).

Five years after the shooting, Sutton continues to deal with the physical toll. His doctor told him that when they shot him in the forearm, it blew the nerves out. The nerves are damaged permanently. He cannot do much with his left hand. His grip tires easily. It is tough for him to extend his hand (The Jersey Vindicator).

As an HVAC technician, working in his field has become nearly impossible. How can he pick up ducts and deal with machinery and equipment with nerve damage? The shooting has derailed his ability to earn a living and support his five children (The Jersey Vindicator).

Research shows that Black Americans who live in neighborhoods with higher rates of police violence experience worse mental health outcomes. A study published in the Lancet found that police killings of unarmed Black Americans have significant effects on the mental health of Black Americans living in the same states. These killings lead to increased depression and emotional distress that can last for months (National Institutes of Health).

Attempts at Reform and Why They Keep Failing

After every high-profile police killing, there are calls for reform. Police departments implement trainings on implicit bias, mindfulness, de-escalation, and crisis intervention. They diversify department leadership. They create tighter use-of-force standards. They adopt body cameras. They initiate police-community dialogues. They implement enhanced early-warning systems to identify problem officers (ACLU).

Minneapolis implemented all of these reforms before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin in 2020. The city was one of the cities piloting the Obama administration’s National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice. The hope was that these training programs would professionalize policing and reduce abuses. None of it worked (ACLU).

Similar patterns emerged in Newark in 1967, in Detroit in 1967, in Harlem in 1935, and in Chicago in 1919. After each uprising, commissions were formed. Reports were written. Recommendations were made. The reports all identified the same problems: police brutality, racial discrimination, poverty, unemployment, inadequate housing, and poor schools. The recommendations were ignored. Police violence continued. Another uprising eventually followed (ACLU).

The Kerner Report of 1968 found that the root causes of uprisings were disinvestment in Black communities, Black powerlessness and frustrated hopes, and how police symbolize white power, white racism, and white repression for significant numbers of Black people. President Lyndon B. Johnson ignored most recommendations and set aside the findings. Instead, he launched the War on Crime, sending militarized police forces into impoverished Black neighborhoods (Yale University).

Facing increasing surveillance and brutality, residents responded with protests. Police responded with more violence. The results are the hugely expanded policing and prison regimes that shape the lives of so many Americans today (Yale University).

What Accountability Actually Looks Like

Real accountability requires more than training and body cameras. It requires removing the legal shields that protect officers who violate constitutional rights. Three states have passed laws limiting qualified immunity: Colorado, Connecticut, and New Mexico. These laws make it easier for victims of police violence to hold officers accountable (Everytown Research).

Accountability also requires prosecutors willing to bring charges against police officers. However, prosecutors work closely with police departments. They depend on police to investigate cases and testify in court. This creates a conflict of interest that makes it difficult for prosecutors to charge officers (National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers).

Financial accountability matters too. When police departments and municipalities pay settlements for misconduct, taxpayers foot the bill. Officers face no personal financial consequences. Some advocates argue that officers should be required to carry liability insurance, similar to doctors. This would create a financial incentive for individual officers to avoid misconduct (Equal Justice Initiative).

Community oversight boards with real power to investigate complaints and discipline officers are essential. However, many existing civilian review boards lack subpoena power, cannot compel officers to testify, and can only make recommendations that police chiefs often ignore. Effective oversight requires boards with the power to access evidence, question officers, and impose discipline (National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers).

Why This Matters Today

Jeffrey Sutton’s case matters because it exposes the lie that police brutality is about a few bad apples. The Bloomfield Police Department has systemic problems documented by multiple studies. Officers routinely target Black and Latino drivers. They file false reports. When caught lying, they face no consequences. Officers get promoted (Bloomfield Police Department).

This matters because the same patterns that emerged during slavery continue today. The fundamental purpose of policing in America has always been to control Black bodies and extract wealth from Black communities. Slave patrols caught escaped slaves. Jim Crow police enforced segregation. Modern police departments generate revenue by targeting Black and Latino drivers with tickets and fines (Seton Hall Law Center for Policy & Research).

This matters because without video evidence, Jeffrey Sutton would be in prison right now. He would be serving decades for crimes he did not commit based on police reports that were complete fabrications. How many people are in prison today because there was no video? How many were killed before someone nearby had a camera phone? (News 12 New Jersey)

This matters because it reveals that the system is working exactly as designed. Police are not held accountable because the legal system protects them through qualified immunity. Body cameras do not stop police violence because officers control when cameras are on and departments control when footage is released. Training programs do not work because they do not address the fundamental problem: policing in America is rooted in racism and designed to control Black people (ACLU).

This matters because the trauma is real and ongoing. Sutton cannot work in his profession. He lives with chronic pain and nerve damage. He spent three years in jail for defending himself from what he reasonably believed was an armed robbery. His children grew up without their father. All because police in Bloomfield decided to ambush a Black man and then lie about it (The Jersey Vindicator).

This matters because every day, Black people across America face similar treatment. They get pulled over for driving while Black. They get stopped and frisked for walking while Black. They get shot for holding a cell phone that an officer claims looked like a gun. They get choked to death for selling loose cigarettes. They get killed in their own homes during no-knock raids (Al Jazeera).

The history tells us this will not stop through reform alone. For more than 100 years, commissions have studied police brutality, written reports, and made recommendations. The violence continues because the system is designed to produce these outcomes. Real change requires dismantling qualified immunity, defunding militarized police departments, and investing in communities. It requires holding officers personally and financially accountable. It requires prosecutors who are independent from police departments. It requires acknowledging that policing in America is rooted in slavery and white supremacy (ACLU).

Jeffrey Sutton is still seeking justice five years after he was shot. His federal lawsuit against Bloomfield and its police department continues. Meanwhile, the officer who shot him and lied about it now serves as Deputy Chief of Police, overseeing the daily operations of uniformed personnel (Bloomfield Police Department). That tells you everything you need to know about police accountability in America.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.