Data Centers, Environmental Racism, and the Fight for Community Power in Bessemer, Alabama

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Bessemer Says No to Data Center Extraction and Environmental Injustice

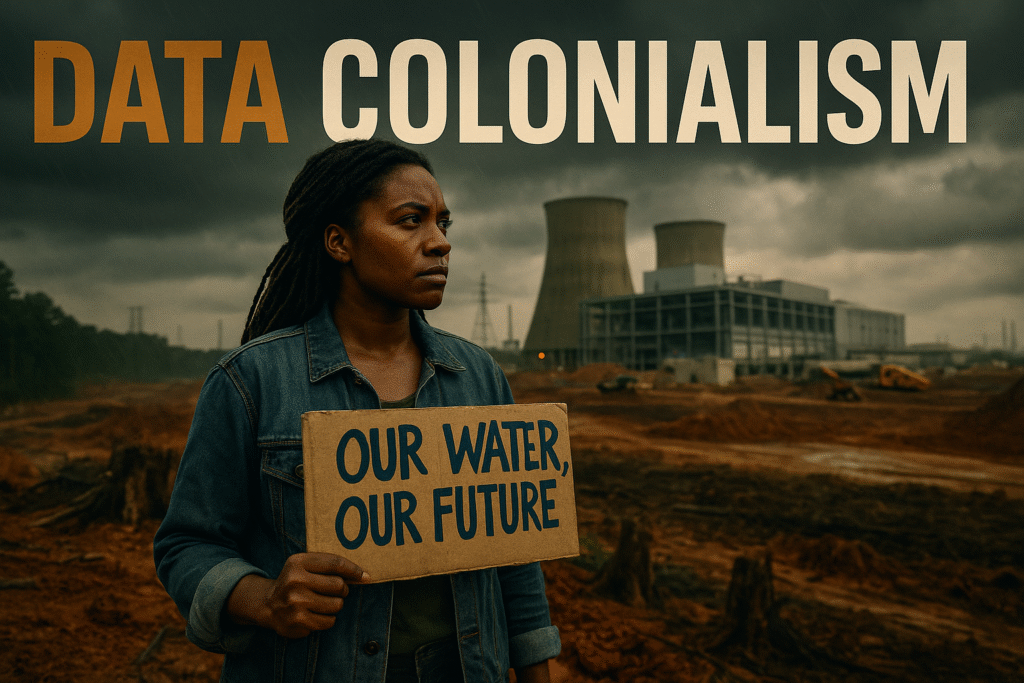

In late October 2025, the Bessemer City Council voted to change zoning laws, clearing the path for Project Marvel. This $14-15 billion data center would cover 700 acres of forest on the edge of majority-Black Bessemer, Alabama. The vote came despite serious opposition from residents, the NAACP, environmental groups, and local advocacy organizations. Underneath the promise of technological progress lies a troubling pattern. Bessemer residents see this data center as another extraction project—one that will drain their water, degrade their air, and enrich corporations while leaving their community worse off. The residents are demanding something different: a legally-binding community benefits agreement that ensures local jobs, environmental protections, and real investment in their neighborhoods.

What project officials presented as progress began to feel like extraction the moment residents did the math. Project Marvel requires 2 million gallons of water daily—water the region cannot spare. The facility demands 1,200 megawatts of electricity, enough to power a city the size of Seattle. Clearing 700 acres of forest means destroying habitat and losing carbon-absorbing trees. The facility itself will span 4.5 million square feet, equivalent to eighteen Walmart Supercenters stacked together. Moreover, city leaders signed non-disclosure agreements with the developers, keeping crucial details about the project hidden from the very people who will live with its consequences.

Behind Closed Doors: Government Secrecy and Corporate Power

The lack of transparency infuriates Bessemer residents and NAACP officials alike. Mayor Kenneth Gulley, his chief of staff, and the city attorney all signed non-disclosure agreements preventing them from discussing Project Marvel details publicly. This meant government officials could not explain the project to their constituents. Some city council members may have signed the same agreements. During a packed city council meeting, many residents could not even get inside the chamber to voice their concerns. When the NAACP demanded public records related to the project under Alabama’s Open Records Act, they requested documentation of the NDAs themselves, water usage analyses, environmental impact studies, and disaster management plans. So far, these records remain largely hidden.

Moreover, the rezoning vote was presented as a general change to allow data centers in light industrial zones. City council president Donna Thigpen insisted the vote had nothing specifically to do with Project Marvel. Yet the timing and the rezoning of the exact parcel where Marvel is proposed to sit suggest otherwise. Benard Simelton, president of the NAACP Alabama State Conference, captured community frustration in a simple question: “If this was really good for the community, why all the secrecy?”

A Community Already Drowning in Pollution and Fossil Fuel Emissions

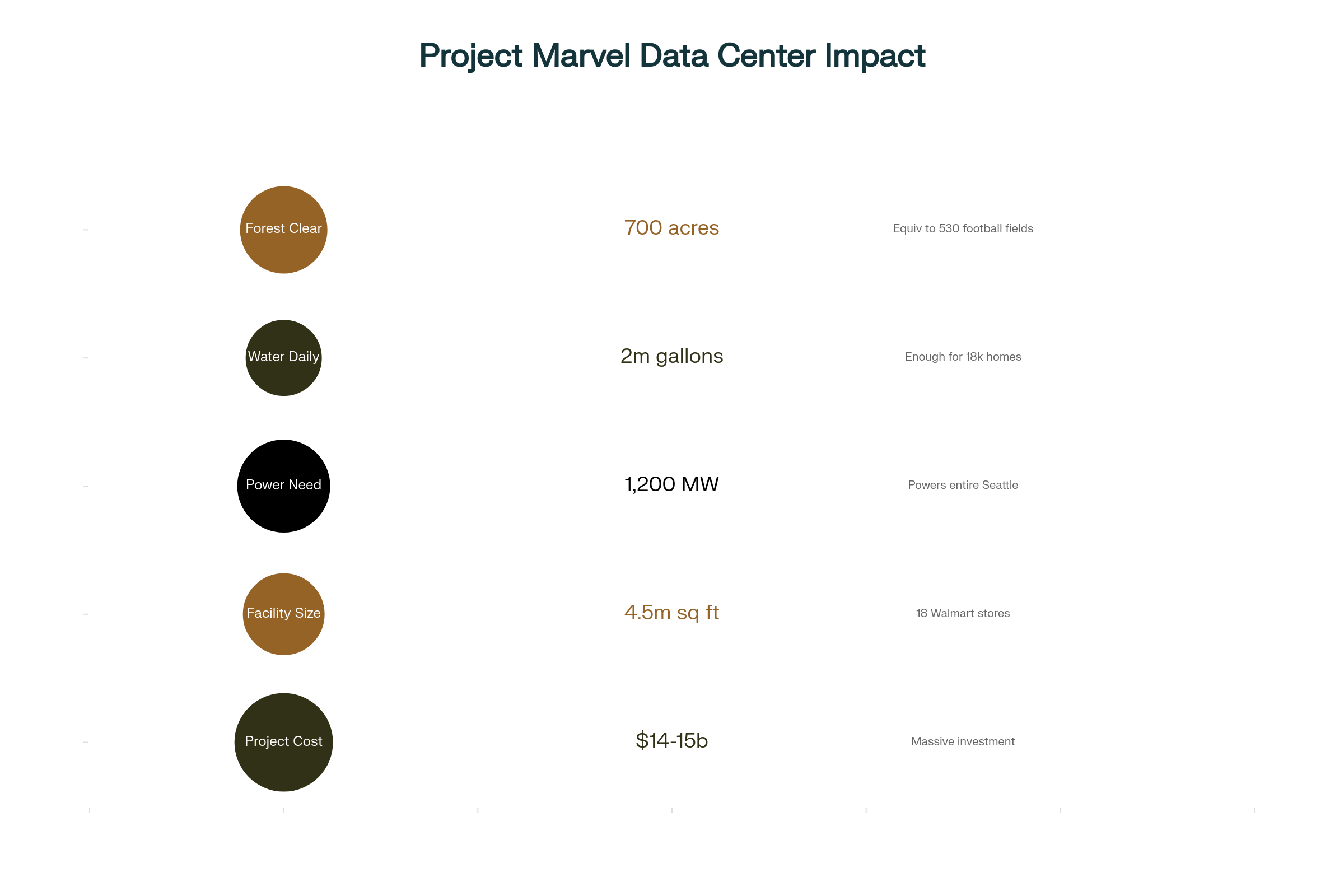

Bessemer did not wake up yesterday to environmental problems. The city has endured industrial pollution for generations. Jefferson County is home to one of the single-largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the entire United States: the coal-fired James H. Miller Jr. Electric Generating Plant located in nearby West Jefferson. In 2022, this plant alone emitted nearly 22 million metric tons of greenhouse gases—more than 21 million tons of carbon dioxide plus methane and nitrous oxide emissions. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, this coal plant ranks as the nation’s worst greenhouse gas polluter year after year. It releases more greenhouse gases than some entire countries.

That coal plant sits in a community of fewer than 500 people. Most residents there cannot speak publicly about its impact—the economic weight of Alabama Power’s presence in their small town silences them. Yet the plant employs over 300 people, tying the community’s survival to its continued operation. This is the trap of industrial development in low-income communities. Consequently, Bessemer and surrounding areas already have some of the worst air pollution in the Southeast. The American Lung Association ranked the Birmingham metro area the 71st most polluted for ozone and third worst in the entire Southeast. Residents in Bessemer already fight for cleaner air. They already bear the health burdens of industrial emissions.

Environmental Racism and the Concentration of Pollution in Black Communities

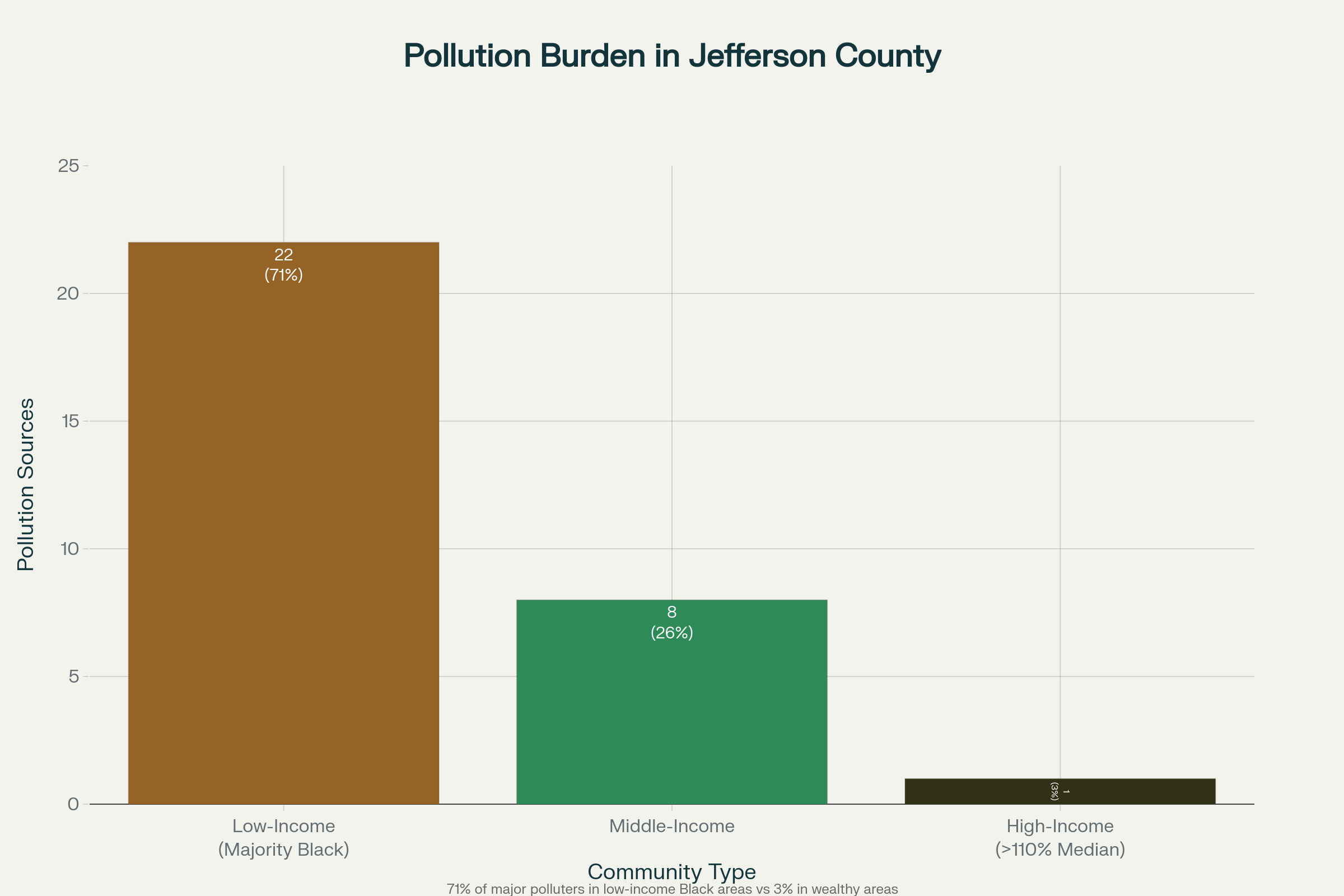

The concentration of pollution in Bessemer and Jefferson County is not accidental. It is the result of deliberate policies, racist zoning laws, and a system that treats Black neighborhoods as sacrifice zones. Analysis by Birmingham Watch found that 71 percent of Jefferson County’s 31 major sources of industrial pollution are clustered in low-income areas. The majority of residents in those same areas are African American. Only one major pollution source is located in a neighborhood with median household income greater than 110 percent of the county median. This pattern reveals the workings of environmental racism, a system that concentrates toxic industries in Black communities while keeping wealthy white neighborhoods clean.

This did not happen by chance. Historic redlining—the practice of marking predominantly Black neighborhoods as risky investment—boxed African Americans into industrial zones near their employers. White flight expanded the suburbs and added vehicle emissions to the problem. The result is what the Jefferson County Health Department calls “the perfect storm” of air pollution. Data centers only make matters worse. These facilities demand enormous amounts of electricity, most of which will come from fossil fuel power plants like the Miller plant. They also require massive water consumption for cooling. Placing another massive polluter in an already overburdened community compounds generations of environmental injustice.

Bessemer’s Industrial Past: A City Built on Steel, Coal, and Broken Promises

Understanding why Bessemer fights Project Marvel means understanding the city’s history. In 1887, coal magnate Henry F. DeBardeleben founded Bessemer as a planned steel center. He named it after English steelmaster Sir Henry Bessemer. The city grew rapidly, attracting rural migrants from across the South and European immigrants seeking industrial work. At its height, Bessemer was a manufacturing powerhouse. Bessemer convertersâ€- machines used in steel productionâ€- were revolutionary. Steel rail, railroad cars, structural materials, chemicals, and explosives poured from Bessemer’s factories. By 1911, Bessemer ranked among Alabama’s largest producers of ore, iron, and coke. The city seemed destined for endless prosperity.

But industrial prosperity came with a price—pollution. Even in the early 1900s, Bessemer converters discharged about 17 pounds of toxic fumes per ton of product. An average converter would discharge 10 tons of fumes daily into the air. None of these converters were equipped with air-cleaning devices because no reasonable solution existed. Residents breathed polluted air as the cost of having jobs. Gradually, African Americans moved into industrial jobs in Bessemer and across the region. Some achieved middle-class incomes through manufacturing work. Yet they lived near the factories they worked in, breathing the pollution those factories produced. Thus, from Bessemer’s founding, Black workers bore the environmental cost of the region’s industrial wealth.

Deindustrialization, Devastation, and the Search for Economic Renewal

Bessemer’s industrial economy collapsed in the late twentieth century. Steel companies restructured, moving operations overseas or replacing coke-fueled furnaces with cleaner electric ones. Mining operations exhausted Alabama’s ore supplies. The railroad industry declined, and Pullman Standard’s massive railcar factory—once a pillar of Bessemer’s economy—ceased most production in the 1990s. Bessemer lost thousands of jobs and tens of thousands of residents. Population peaked at around 33,000 in 1970, then fell steadily. By the 1980s, unemployment exceeded one-third of the workforce. Businesses fled. People moved away seeking better opportunities. The exodus of the 1970s and 1980s left Bessemer hollowed out, with abandoned factories and boarded-up storefronts.

As businesses left, so did the tax base. Remaining residents, many of them African American workers and retirees, faced a city with fewer resources for schools, public services, and infrastructure. Yet the pollution remained. Plants that stayed operated with less oversight. Regulators tended to prioritize keeping remaining industries in business over strict enforcement of environmental rules. In this context, politicians and developers began pitching new development projects as salvation. Amazon announced an 800,000-square-foot fulfillment center in 2018. Now, Project Marvel promises investment, technological innovation, and jobs. To residents traumatized by deindustrialization, these promises sound appealing. Yet history suggests caution.

The Racial Segregation and Civil Rights Legacy of Birmingham-Bessemer

Bessemer’s current struggle for environmental justice and community power must be understood within the context of Birmingham-Bessemer’s brutal civil rights history. In 1960, Birmingham’s population was split 60-40, white over Black. Bessemer was majority Black and overwhelmingly poor. Yet racial segregation was absolute, legally required, and ruthlessly enforced. Eugene “Bull” Connor, the Commissioner of Public Safety, was a virulent racist with connections to the Ku Klux Klan. His police force—some members of whom were Klansmen—brutalized Black citizens enforcing the racial status quo. Between 1957 and 1963, Black churches and homes of Black leaders were bombed 17 times. Jewish synagogues were also bombed. The city earned the nickname “Bombingham.”

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) organized relentlessly despite the violence and intimidation. They held mass meetings every Monday night for months and years. They forced integration of Bessemer buses. Shuttlesworth was jailed many times. His church was bombed. In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Birmingham, calling it “probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States.” The campaign brought national attention to the city’s racial brutality. Yet segregation by law ended while segregation by economics and geography continued. Black workers remained concentrated in industrial zones. They continued to breathe polluted air. Systemic racism adapted to post-Civil Rights America, operating through zoning laws, real estate practices, and industrial policy rather than explicit legal segregation.

Data Centers as the New Extraction Economy: High Tech, Same Environmental Racism

Project Marvel represents a new form of extraction dressed in technological language. Data centers power artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and digital infrastructure. They are presented as symbols of progress and the future. Yet they are intensely resource-intensive operations. A single 100-megawatt data center consumes about 2 million liters of water daily—equivalent to the water consumption of about 6,500 households. Globally, data centers now consume approximately 560 billion liters of water annually, with consumption expected to rise to 1.2 trillion liters by 2030 as AI demand accelerates. Data centers typically evaporate about 80 percent of the water they draw, discharging only 20 percent back to treatment facilities. This compares poorly to residential water use, which loses only 10 percent to evaporation.

Most concerning, roughly two-thirds of new data centers built or in development in the United States since 2022 are located in places with high levels of water stress. Meanwhile, tech companies negotiate preferential water rates unavailable to residents. In Mesa, Arizona, Google negotiated a deal to pay $6.08 per 1,000 gallons of water while residents paid $10.80 per 1,000 gallons. This practice undercuts conservation incentives and ensures corporations use water without bearing its full cost. Project Marvel in Bessemer would use 2 million gallons of water daily. It represents the prioritization of corporate profit over community survival.

Community Benefits Agreements: What Bessemer Residents Are Demanding

Bessemer residents and the NAACP are not simply saying no to Project Marvel. They are proposing an alternative model: the community benefits agreement (CBA). A CBA is a legally binding contract between a developer and community stakeholders negotiated before a project receives final approval. CBAs can address workforce concerns, environmental protections, and community investment. For example, a CBA might require a developer to establish a fund supporting economic diversification through workforce training. It might mandate hiring local residents for project jobs and ongoing operations. It might fund affordable housing, childcare, parks, or preservation of historic sites. Communities can also ensure environmental protections are included—requiring water conservation technologies, limiting air pollution, mandating regular health monitoring, or establishing community oversight mechanisms.

Research shows that CBAs work. Fifty-nine percent of local voters support CBAs, and 62 percent say they would support using a CBA for a development project in their community. When negotiated well, CBAs streamline permitting processes for developers while giving communities real say in projects affecting their lives. For Bessemer, a CBA for Project Marvel could require: local hiring for all construction and permanent jobs; establishment of a workforce training program for area residents; a community benefits fund for environmental restoration and public health monitoring; water conservation technologies and limits on daily water consumption; commitment to renewable energy sources; regular environmental impact audits with community access to results; and direct community representation on any project oversight committee. Most importantly, a CBA would shift power from corporations and government officials to Bessemer residents themselves.

Why This Matters Today: Fighting Environmental Racism and Reclaiming Community Power

The fight over Project Marvel is not just about Bessemer. It is a battle over who benefits from technological progress and who pays its cost. For generations, Black communities have subsidized America’s prosperity—through slavery, segregation, exploitation of labor, and now through environmental racism. Bessemer residents have already paid enough. They have breathed polluted air from steel mills, coal plants, and coke ovens. They watched their children suffer respiratory illnesses caused by industrial emissions. They saw their city decline as corporations moved operations elsewhere. They are telling corporations and government officials: this community is not for sale. Our water is not yours to drain. Our air is not yours to further poison. Our future belongs to us.

The NAACP’s opposition to Project Marvel reflects a national shift in environmental justice organizing. The organization’s Frontline Framework, developed with frontline communities and activists fighting data centers across the country, asserts that communities have the right to a future rooted in dignity, clean air, and self-determination—not in choosing between economic survival and their health. Abre’ Conner, NAACP Director of Environmental and Climate Justice, stated: “Communities like Bessemer have borne the brunt of toxic industries for far too long. Adding yet another major polluter into a majority-Black community already burdened by some of the highest greenhouse gas emissions in the nation is unacceptable.” This represents a refusal to accept the false choice between development and environmental protection.

The moment is critical. The Bessemer fight will set precedent. If Bessemer residents force Project Marvel developers to accept a strong CBA, it sends a message to tech companies and other corporations nationwide: extractive development will face organized resistance. If residents organize and win, they protect their community and inspire other communities to demand the same. Conversely, if Project Marvel proceeds without meaningful community benefits and local control, it will embolden other corporations to target Black communities with similar projects. Bessemer residents understand these stakes. They are fighting not just for their city but for the future of Black communities nationwide.

About the Author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.