Libya Shipwrecks: Deadly History for African Migrants

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Perilous Crossing Rooted in History

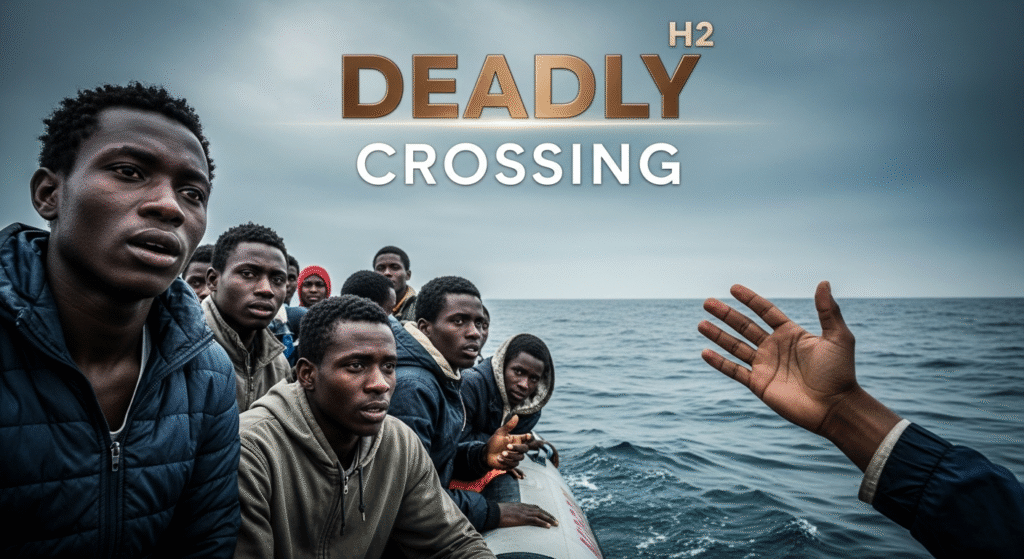

The recent capsizing of two migrant boats off Libya’s Al-Khums coast is a heartbreaking, yet familiar, story. At least four people died, with others still missing, after Libyan Red Crescent teams recovered bodies from the sea (reliefweb.int). The passengers, primarily from Bangladesh, Sudan, and Egypt, were undertaking a journey that has claimed thousands of lives. These headlines, however, only scratch the surface of a deep and painful history. The crisis in the Central Mediterranean is not a series of random accidents. Instead, it is the predictable result of geopolitical collapse, racist violence, and European policies that create deadly barriers instead of safe passages.

To understand today’s tragedies, we must look back to 2011. Before the uprising that overthrew Muammar Gaddafi, Libya was a destination for African workers, its oil economy drawing people from across the continent (mixedmigration.org). The ensuing civil war and political instability shattered that reality. The country’s border controls disintegrated, and a power vacuum allowed human smuggling networks to flourish. Consequently, Libya transformed from a place of opportunity into the primary transit point for one of the most dangerous migration routes in the world (mixedmigration.org). This chaos laid the groundwork for the exploitation and suffering that defines the journey today.

Anti-Black Racism on the Migrant Route

For Black African migrants, the journey through Libya is not just dangerous; it is a nightmare defined by extreme racial hatred. The end of Gaddafi’s rule exposed a deep-seated anti-Black sentiment within Libyan society (wilsoncenter.org). Black people, including migrants and even Black Libyans, became targets of raids, arbitrary arrests, assaults, and murders, often fueled by hateful rhetoric from government officials (thearabweekly.com). This racism is so ingrained that Black Africans are often called “abeed” or “abd,” the Arabic word for slave, a painful echo of a history of chattel slavery in the region.

This deep-seated racism directly shapes the horrific experiences of migrants. A 2021 United Nations report found that Black sub-Saharan Africans are especially vulnerable to harsher treatment than other migrant groups in Libya (e-ir.info). Survivors have explicitly stated that “Libya isn’t a safe place for Black Africans” because of the racism they face (e-ir.info). Moreover, interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch revealed widespread violence and discrimination from both authorities and private citizens, with Black migrants often too afraid to report crimes against them (hrw.org). The color of their skin makes them a target, compounding every other risk they face.

Migrant Demographics in Libya

- Sudanese (31%)

- Nigerien (22%)

- Egyptian (20%)

- Chadian (10%)

- Other (17%)

Data shows the largest groups of migrants residing in Libya in early 2025 (iom.int).

EU Border Policies and Systemic Harm

European Union migration policies play a direct role in perpetuating this cycle of violence. For years, the EU has pursued a strategy of “externalizing” its borders, paying and equipping North African countries to stop migrants before they can reach European shores (mixedmigration.org). This involves providing substantial funding and support to the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept boats and forcibly return people to Libya, the very place they are desperate to escape. These policies effectively trap migrants in a system of abuse, all in the name of border control.

From a racial justice perspective, these policies are catastrophic and disproportionately harm Black lives. By empowering Libyan militias and security forces, the EU is complicit in the human rights abuses they commit (equaltimes.org). Critics argue the EU’s silence on the rampant racist violence in Libya amounts to tacit encouragement, so long as it serves the goal of preventing migration (uua.org). For this reason, Amnesty International has condemned these policies as “draconian,” highlighting the strong evidence of torture of sub-Saharan Africans in EU-supported detention centers (amnesty.org). Europe’s border is effectively being enforced at the expense of Black bodies.

Colonial Legacies Fueling African Migration

The reasons people risk their lives to cross the Mediterranean are complex and deeply rooted in global injustice. The official “push factors” are listed as generalized violence, conflict, and economic distress (mixedmigration.org). This explanation, however, fails to address the historical context. The instability plaguing many African nations is a direct legacy of colonialism, neo-colonialism, and centuries of resource exploitation (moderndiplomacy.eu). Artificial borders drawn by colonizers, coupled with economic systems designed to benefit Europe, have created the conditions for the perpetual conflict and poverty that force people from their homes.

Many migrants come from countries like Sudan, Nigeria, Eritrea, and Somalia, all of which have experienced prolonged conflict and repression often inflamed by external interests. The chaos in Libya became fertile ground for exploiting these existing vulnerabilities. The trafficking, extortion, and public abuse of Black migrants in post-Gaddafi Libya represents the weaponization of Black bodies in a failed state (sandiego.edu). Therefore, migration is not simply a choice; for many, it is the only option left in a world systemically structured against them.

The Staggering Human Cost of African Migration

The statistics surrounding the Central Mediterranean route reveal a crisis of immense scale. It remains one of the deadliest migration routes in the world (reliefweb.int). In 2024, the route claimed over 1,700 lives, and globally, it was the deadliest year on record for migrants, with over 8,700 fatalities. The death toll for 2025 has already surpassed 1,300 people (iom.int). The long-term numbers are even more horrifying. Between 2014 and 2020, an estimated 20,000 migrants lost their lives trying to reach Italy from North Africa (iemed.org). This consistent loss of life represents a profound failure of the international community.

While the death rate remains high, the number of people detected making the crossing has recently fallen. After a 55% increase in crossings via this route in 2023, numbers dropped by 64% in the first nine months of 2024 (europa.eu). This decline continued into the first quarter of 2025 (europa.eu). Yet, this does not mean the crisis is over. In early 2025, Libya still hosted an estimated 858,000 migrants, with the largest groups being Sudanese, Nigerien, and Egyptian (iom.int). Thousands remain trapped in the country, facing abuse and waiting for a chance to escape.

Global Anti-Blackness and the Fight for Justice

The horrors in Libya are a modern expression of an ancient crime. When a 2017 CNN report revealed that Black Africans were being auctioned off as slaves for as little as $400, it sent shockwaves across the globe (youtube.com). The United Nations condemned these “heinous abuses,” but the images of Black men being sold like property were a chilling reminder of the transatlantic slave trade (jpost.com). This is more than just human trafficking; it is the commodification of Black bodies, rooted in a global system of anti-Blackness that has devalued our lives for centuries (moderndiplomacy.eu). This crisis is a frontline in the ongoing struggle for Black humanity.

While international human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have worked tirelessly to document these racialized abuses, the political response has been inadequate. The African Union, in particular, has been criticized for its “deafening silence” and failure to take decisive action to protect Africans from being enslaved on African soil (moderndiplomacy.eu). Ultimately, the fight for justice for these migrants is inseparable from the broader struggle for Black liberation. It connects our fight for dignity in America and across the diaspora to the shores of the Mediterranean, reminding us that an injustice to Black people anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.