EU Plan for East Africa Transit Centres

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

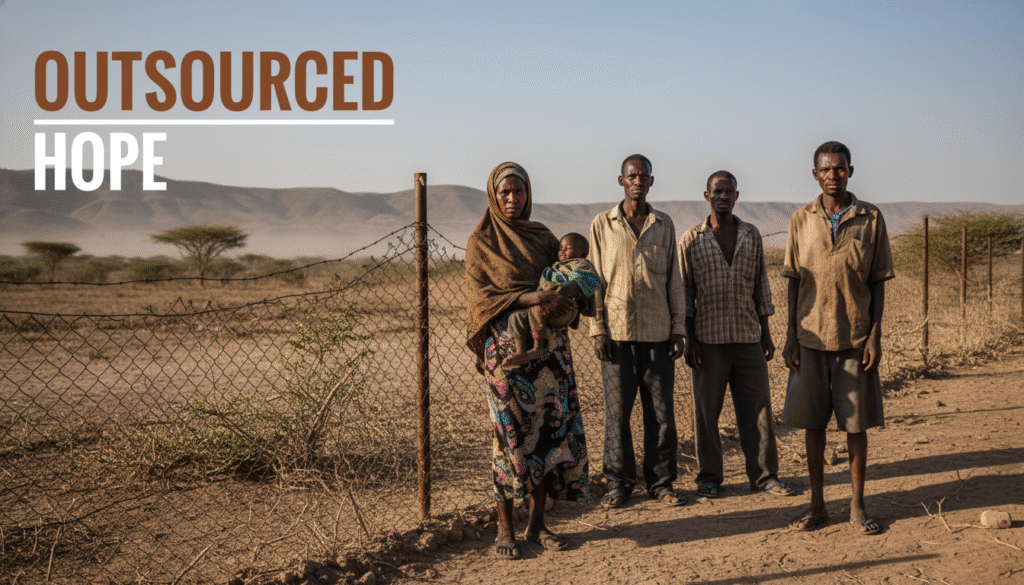

A leaked document from Austria is once again shining a light on the European Union’s long and troubled history with migration policy. The proposal suggests creating “transit centres” in East African countries to process asylum seekers, including those whose claims have been rejected (amazonaws.com). For many in the African diaspora, this plan is not new. Instead, it represents the latest chapter in a decades-long effort by Europe to push its asylum responsibilities onto other nations, often with devastating human consequences. Human rights organizations warn that these remote camps would operate with little oversight, creating harsh conditions and hiding abuse from public view (amazonaws.com).

This push to externalize borders has deep historical roots. Critics argue that these policies are not only inhumane but also expensive and unworkable in the long run. They point to the need for fair and robust asylum systems within Europe itself. Consequently, the debate raises fundamental questions about international law, human rights, and the value placed on the lives of those seeking safety, many of whom are fleeing conflict and persecution in Africa and the Middle East.

The Roots of Fortress Europe Policy

The idea of processing asylum claims outside of Europe is a recurring theme in the EU’s migration policy discussions. The foundation for a common EU policy began to solidify with the Amsterdam Treaty, which came into force in 1999 ((europa.eu), (etias.com)). This treaty moved asylum and immigration policies under the control of the EU’s central institutions, paving the way for a unified approach to border management (emnbelgium.be). It aimed to create an “area of freedom, security and justice” by strengthening external borders while allowing free movement inside the EU (europa.eu).

Early proposals for offshore processing emerged soon after. In 2003, the United Kingdom suggested creating “Regional Protection Areas” near refugee-producing countries (amazonaws.com). Germany followed in 2005 with a similar plan for asylum centers in North Africa (amazonaws.com). These initial ideas did not gain traction due to legal challenges and human rights concerns. However, they revealed a consistent desire among some European leaders to keep asylum seekers away from European soil. A major influence has been Australia’s controversial “Pacific Solution,” which involved sending asylum seekers to offshore centers in Nauru and Papua New Guinea ((amazonaws.com), (sbs.com.au)). That policy has been widely condemned for its high financial costs and severe human rights abuses, including deaths and prolonged detention (amazonaws.com).

Externalization: Europe’s Migration Policy Keyword

The core strategy behind these proposals is “externalization,” which relies heavily on the “safe third country” concept. This allows EU member states to return asylum seekers to countries they passed through, even if they have no connection to that nation (amazonaws.com). This approach intensified after the significant increase in migration between 2015 and 2016. At the time, Europe saw a surge in people arriving, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan, and other conflict zones (europa.eu). Many of these individuals were undertaking what is known as irregular migration, which is the movement of people across borders without following the legal requirements for entry or stay ((cmsny.org), (europa.eu)).

In April 2024, the EU adopted the Pact on Migration and Asylum, a major reform of its asylum system (equaltimes.org). The pact aims to create a more efficient process by enhancing external border management and establishing faster asylum and return procedures ((europa.eu), (europa.eu)). It includes a mandatory “solidarity mechanism” that requires member states to either relocate asylum seekers from countries under pressure or provide financial support (hrw.org). While presented as a comprehensive solution, the pact’s emphasis on rapid border procedures and returns has been criticized for reinforcing the externalization trend. Consequently, human rights groups worry it could weaken protections for vulnerable people.

Today’s Proposals, Yesterday’s Problems

The leaked Austrian plan for “transit hubs” in East Africa is the latest manifestation of this long-standing policy desire (amazonaws.com). The proposal specifically targets rejected asylum seekers, regardless of their home country (amazonaws.com). Though Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer has openly supported outsourcing asylum procedures, no specific East African country has been officially named as a partner ((euobserver.com), (euobserver.com)). This suggests the concept is still a political ambition rather than a concrete plan.

This proposal mirrors other recent European initiatives. For example, the Italy-Albania deal involves transferring asylum seekers rescued at sea by Italy to centers in Albania for processing (amazonaws.com). Italian officials claim this is not “outsourcing” because the centers will operate under Italian jurisdiction with Italian law applied by Italian personnel (esteri.it). Nevertheless, critics argue that moving asylum processing to a non-EU country creates a legal grey area and undermines fundamental rights (verfassungsblog.de). Furthermore, the EU has also established migration partnerships with Tunisia, Egypt, and Mauritania, providing them with funds for border management despite serious human rights concerns in those nations ((amazonaws.com), (middleeastmonitor.com), (aljazeera.com)).

The Human Cost of Outsourcing Asylum

Human rights groups have consistently sounded the alarm over these externalization plans. Organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the UNHCR—the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, which is the UN agency mandated to protect refugees—warn of severe risks ((brookings.edu), (amazonaws.com), (amnesty.org)). Their primary concern is that remote camps are difficult to monitor, which increases the likelihood of abuse, neglect, and inhumane living conditions (amazonaws.com). Outsourcing asylum also creates a high risk of *refoulement*, which is the act of sending people back to a country where they face persecution or harm, a clear violation of international law (amazonaws.com).

These policies often trap individuals in prolonged arbitrary detention and a state of legal limbo, denying them access to lawyers and fair legal processes (amazonaws.com). Critics argue that the entire model undermines the right to seek asylum by creating barriers that prevent people from ever reaching a jurisdiction where their claim can be fairly heard. Moreover, when abuse occurs in these third-country centers, holding European agencies accountable becomes incredibly difficult. These deals also lend legitimacy to authoritarian regimes, weakening the EU’s credibility as a global defender of human rights (amazonaws.com).

EU Return Rate for Non-EU Citizens (2020)

Only a small fraction of non-EU citizens ordered to leave the EU actually returned in 2020. Data source: European Commission.

The Numbers Driving Migration Policy

The political urgency behind these policies is often driven by statistics on asylum and migration. In 2023, over 1.14 million people applied for international protection in the EU, an 18% increase from 2022 and approaching the record levels seen in 2015-2016 ((europa.eu), (statista.com)). In 2024, EU countries received approximately one million applications and granted protection to 437,900 people (europa.eu). The largest groups of asylum seekers have consistently been from Syria and Afghanistan (europa.eu).

While overall irregular border crossings into the EU fell by 43% in the first 10 months of 2024, certain routes saw dramatic increases (europa.eu). The Eastern Land Border, which includes countries like Latvia, Poland, and Lithuania bordering Belarus, saw a 195% surge ((europa.eu), (wiiw.ac.at)). Meanwhile, the Central Mediterranean route, where migrants depart from Libya and Tunisia aiming for Italy or Malta, remained a major path ((europa.eu), (wiiw.ac.at)). Despite the focus on stopping arrivals, the EU’s return policies are largely ineffective. In 2020, only 18% of non-EU citizens ordered to leave the EU actually departed (amazonaws.com). This low rate is due to practical and legal hurdles, including the refusal of home countries to issue travel documents, difficulty identifying nationalities, and lengthy legal appeals ((emnbelgium.be), (ibanet.org)).

Irregular Border Crossing Trends (Jan-Oct 2024 vs 2023)

While overall irregular crossings decreased, the Eastern Land Border saw a dramatic surge. Data source: Frontex.

A Different Path for Migration Policy

Critics of externalization argue that these policies fail on practical, financial, and moral grounds. The Australian model, for instance, has not been a sustainable deterrent and has cost billions of dollars that could have funded more humane and effective solutions (amazonaws.com). Instead of outsourcing their responsibilities, migration experts and rights groups advocate for strengthening asylum systems inside Europe. This would involve ensuring fair, efficient, and dignified processing for all asylum claims (amazonaws.com).

A key part of this alternative approach is the creation of more safe and legal pathways for people seeking protection. Such pathways would reduce the demand for dangerous, irregular journeys organized by human smugglers and allow people to seek safety without risking their lives. Furthermore, there is a strong call to redirect resources toward comprehensive partnerships with countries in refugees’ regions of origin. These partnerships would need to be based on mutual benefit and human rights, rather than focusing solely on preventing migration to Europe (amazonaws.com).

The leaked Austrian plan is a stark reminder of the central tension in Europe’s migration policy: the desire for strict border control versus its stated commitment to human rights (amazonaws.com). Proponents see externalization as a necessary tool to manage migration, but a long history of failed proposals and human suffering suggests otherwise. Therefore, the path forward requires policies that are both effective in managing migration and unwavering in their defense of the fundamental right to seek asylum. The lives of thousands of people, many from the African continent and its diaspora, hang in the balance.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.