Why The Gambia Migration Crisis Drives Risky Sea Journeys

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

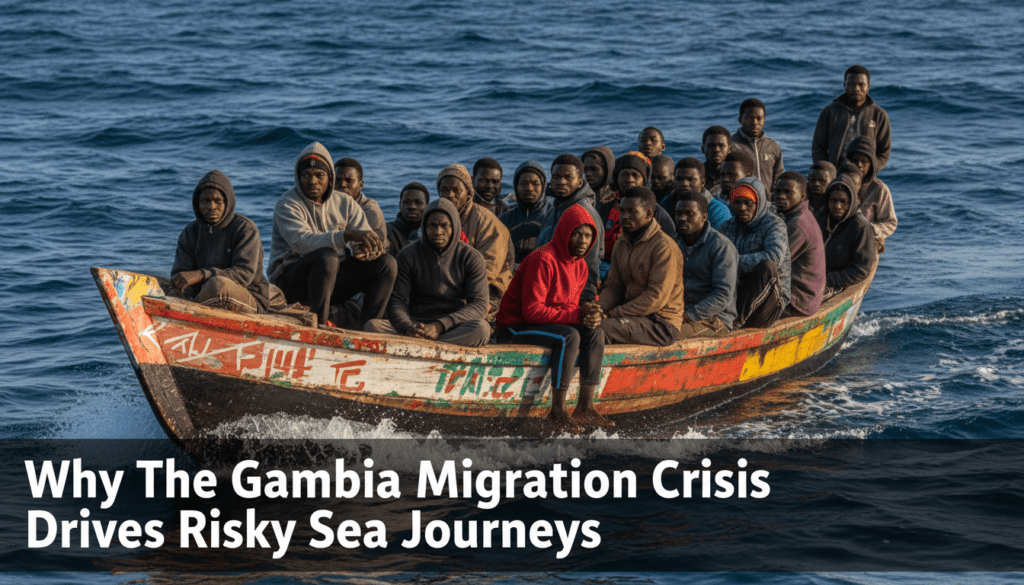

The Atlantic Ocean recently became a scene of tragedy once again. On New Year’s Eve 2025, a boat carrying over two hundred people capsized. This event happened near Jinack Village in The Gambia. Local fishermen and the Gambian Navy worked together to rescue ninety-six survivors. However, at least seven people died during the incident. Many more individuals remain missing in the cold waters of the Atlantic (africa-press.net, theafricandreams.com).

This event is a painful reminder of the dangers people face. These travelers seek a better life in the Canary Islands. The journey covers fifteen hundred kilometers of open sea. It is a path filled with high waves and powerful currents. For many in West Africa, the risk of the ocean is better than the certainty of poverty at home. This tragedy highlights a crisis that has deep historical roots (thepoint.gm).

Record Migration Figures (2024)

Canary Island Arrivals: 46,843

Reported Deaths/Missing: 10,457

Source: Caminando Fronteras

The Ancient Roots of Gambian Movement

Movement is not a new concept in the Senegambia region. History shows that Gambians have always been mobile. During the 19th century, the country relied on seasonal workers. These men were known as “Strange Farmers” or Sama Manila. They traveled from Mali, Senegal, and Guinea to grow peanuts. Peanuts were the primary export for the nation at that time (brill.com, uwpress.org).

This seasonal movement created a culture of migration. People moved to find better land and higher wages. After The Gambia gained independence from Britain in 1965, the economy remained tied to this single crop. This dependency created a fragile financial system. When global peanut prices dropped, the rural poor suffered the most. This history explains why migration is a deeply ingrained survival strategy (africabib.org).

Closing the Front Door to Europe

The term “Backway” refers to irregular migration routes. It became a common phrase in the late 1990s. During this time, European countries began to close legal visa pathways. Many young Gambians found it impossible to get a “front door” entry. Consequently, they turned to the Sahara Desert and the Atlantic Ocean. The closing of legal paths did not stop the desire to move. It only made the journey more dangerous (dyami.services).

The “Backway” is a response to exclusion. In the past, education was the key to traveling abroad. Elite Gambians would go to Europe to study and return. By the turn of the century, this changed. Working-class youth began to see the journey as a necessity for family survival. They look at the Spanish frontier as a place of both peril and potential opportunity (asylumineurope.org).

The Legacy of Political Oppression

Politics played a major role in pushing people away. Yahya Jammeh ruled The Gambia for twenty-two years starting in 1994. His regime was marked by extreme fear and human rights abuses. The National Intelligence Agency and a death squad called the “Junglers” targeted citizens. People were often disappeared or tortured for speaking out against the government (wikipedia.org, wikipedia.org).

This environment forced thousands of young people to flee. They were not just looking for jobs. They were looking for safety from a state that viewed them as enemies. The political crisis of 2016 exacerbated this trend. Even after Jammeh left, the scars of his rule remained. The lack of trust in the state continues to drive the political power of migration as a form of protest (thepoint.gm).

The Economic Impact of Remittances

31.5% of The Gambia’s GDP

Remittance inflows reached $775.6 million in 2024.

Industrial Overfishing and Empty Nets

The Atlantic Ocean used to provide plenty of food for Gambians. Artisanal fishing was a cornerstone of the coastal economy. However, industrial overfishing changed everything. Large trawlers from the European Union and East Asia now dominate these waters. These massive ships can catch up to twenty thousand tons of fish in one year. This amount is equal to what seventeen hundred traditional wooden boats can catch (agrinfo.eu).

Local fishermen find their nets empty day after day. They cannot compete with steel-hulled ships and advanced technology. Because they can no longer fish, many captains have changed their business. They now use their wooden pirogues to transport migrants. The ocean that once fed the community is now seen as a graveyard. This resource depletion is a primary driver of modern migration (worldbank.org).

Structural Adjustments and Poverty

In the 1980s, The Gambia faced economic instability. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank stepped in with loans. These loans came with strict conditions called Structural Adjustment Programs or SAPs. The government had to cut spending on healthcare and education. They also had to stop subsidizing food and farming (worldbank.org).

While these programs helped the national budget, they hurt the people. Poverty became structural and widespread. Small farmers could no longer afford the tools they needed. Job losses in the public sector pushed more people into the informal market. These policies created a “poverty in abundance” where the country had resources but the people remained hungry. This economic shock laid the groundwork for the migration crisis we see today (worldbank.org).

The Modern Middle Passage Connection

For many in the African diaspora, this crisis feels familiar. It is often described as a modern Middle Passage in reverse. Millions of Black bodies are once again crossing the Atlantic in fear. They are following the resources that were extracted from their lands. The struggle for sovereignty over their own waters and labor continues. This journey represents the strength and resilience of a people who refuse to be defeated by systemic inequality (thepoint.gm).

The global economic system still treats African nations as sources of raw materials. Whether it is peanuts or fish, the profit often leaves the continent. Young people feel they must follow that wealth to survive. This connection to the past is vital for understanding the present. The right to stay at home in peace is just as important as the right to move. The current migration crisis is a direct result of historical exploitation (brill.com, wikipedia.org).

Trawler vs. Pirogue Capacity

1 Industrial Trawler

20,000 Tons/Year

1,700 Pirogues

Combined Capacity

Militarized Borders and the Role of Frontex

The European Union has responded to this crisis with increased security. Frontex is the agency responsible for guarding European borders. It has now expanded its operations into West African waters. This is known as “border externalization.” Frontex uses drones and high-tech surveillance to stop boats before they leave the coast. They even embed officers within Gambian border agencies (eucrim.eu, statewatch.org).

Despite these efforts, people still take the risk. Militarization does not address the reason why people leave. It only makes the routes longer and more dangerous. In late 2024, border policies became even stricter under the administration of President Donald Trump. This global shift toward isolationism has left many survivors in legal limbo. They are often held in detention centers or sent back to the very poverty they fled (asylumineurope.org).

The Remittance Lifeline and the Diaspora

Remittances are the money sent back home by Gambians living abroad. This income is a vital lifeline for the nation. In 2024, remittances made up over thirty-one percent of the national GDP. This money is often the only thing keeping families out of extreme hunger. It pays for school fees, medical bills, and new homes. The diaspora has become an essential part of the national economy (worldbank.org).

The “Been-to” culture celebrates those who make it to Europe. Success is often measured by the ability to support the family from afar. This creates a powerful incentive for young men to take the “Backway.” The dream of sending money home outweighs the fear of the ocean. Families often pool their savings to pay for one person to make the journey. This connection to the roots of culture remains strong even across the sea (thepoint.gm).

The High Cost of the Canary Current

The geography of the Atlantic is particularly cruel. The Canary Current flows from north to south along the African coast. If a boat loses its engine, it is pushed away from land. Many vessels drift into the “dead zone” of the open ocean. In these areas, there is no food or fresh water. Survivors of these “ghost ships” often describe horrific scenes of dehydration and despair (thepoint.gm, theafricandreams.com).

The Jinack Village tragedy is one of many such events. The North Bank Region is a common departure point because it has many hidden islands. These spots allow boats to leave without being seen by the authorities. However, the lack of safety equipment on these pirogues is fatal. Most boats do not have life vests or GPS. When a boat capsizes, the chance of survival is very low (dyami.services).

Seeking a Path Toward Justice

Addressing the migration crisis requires more than just patrols. It requires a return to economic sovereignty for West African nations. The Gambian government has tried to implement new migration policies. However, these plans struggle to compete with the immediate need for money. Protecting the fishing industry from foreign exploitation is a necessary first step. Without fish in the sea, there will be no jobs on the shore (agrinfo.eu).

The world must recognize the human dignity of those on the boats. They are not just statistics in a news report. They are sons, daughters, and parents seeking a way to live. The history behind the headlines shows that this is a systemic issue. It is a story of global inequality and the enduring search for a better life. Until the root causes are fixed, the “Backway” will continue to claim lives (wikipedia.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.