Why the Uvira Conflict History and Displacement Crisis Persists

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

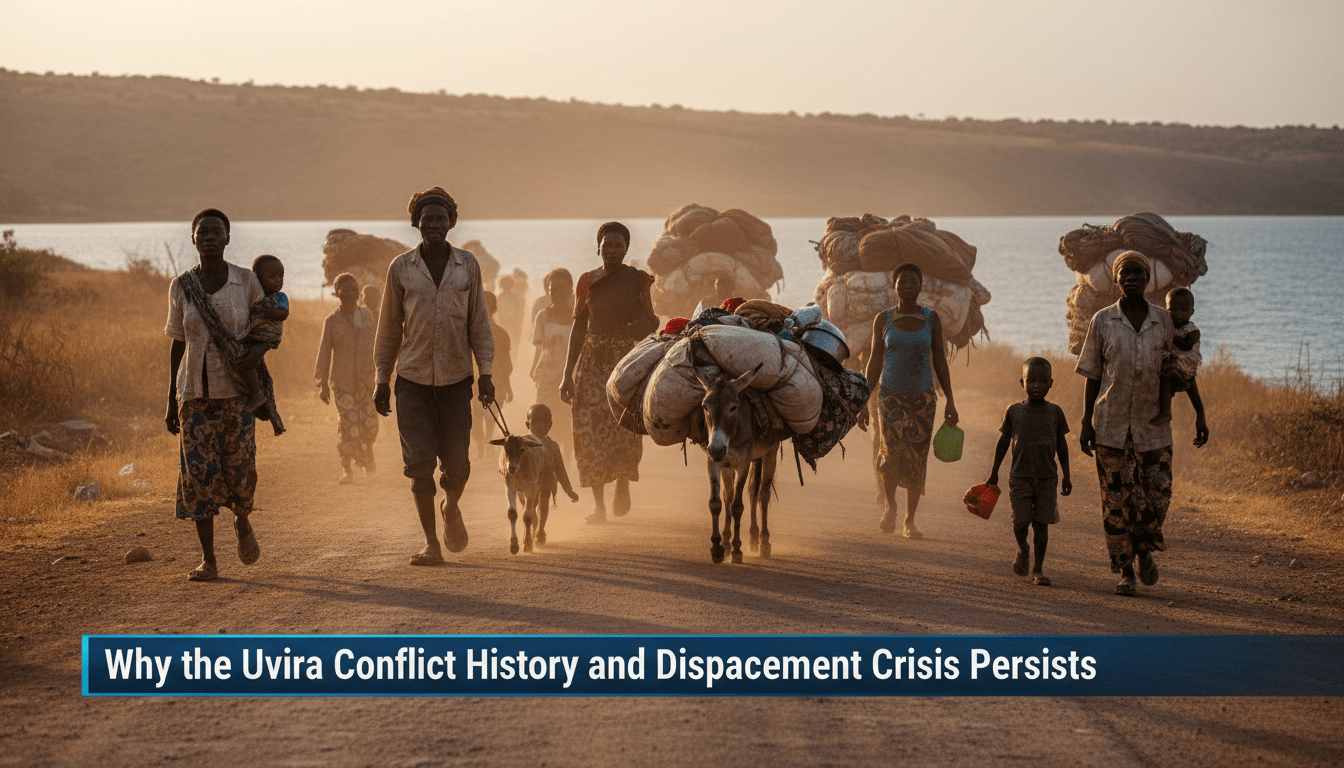

The city of Uvira sits on the edge of Lake Tanganyika in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is a place of beauty but also a place of great pain. Recently, the world watched as Congolese national forces and local militias walked back into the city streets. This happened after the M23 rebel group decided to leave. However, the fighting did not stop in the nearby hills. Families continue to run for their lives. They carry their livestock and heavy bags because they do not know when they can return home (plenglish.com).

The movement of soldiers into Uvira marks a major change in a war that grew worse throughout 2025. The M23 rebels belong to a group called the Congo River Alliance. They said they were leaving Uvira to show they wanted peace. This move happened because of pressure from the United States and meetings in Qatar. However, the government in Kinshasa does not believe the rebels. Officials claim the withdrawal is a trick to hide rebel soldiers within the civilian population (news.cn).

As the soldiers return, the humanitarian situation is getting worse. Aid groups are shouting for help. They see hunger and sickness spreading through the crowds of people who lost their homes. This is more than a simple fight between two groups. It is a part of a long study of African history and the struggle for land and identity. To understand the news today, one must look back at the events that shaped this region over thirty years ago.

The Bloody Legacy of the 1994 Rwandan Genocide

The violence in eastern Congo did not start recently. It is deeply connected to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. During that terrible time, almost one million people were killed in Rwanda. After the killing stopped, more than a million Hutu refugees crossed the border into Congo. Among these refugees were the people who did the killing in Rwanda. They formed a group known as the FDLR. This group became a constant threat to the new government in Rwanda (wikipedia.org).

Because these fighters were in Congo, the Rwandan military crossed the border many times. They said they were protecting their own country. However, these invasions caused a lot of trouble for the Congolese people. It created tension between different ethnic groups who had lived together for a long time. The Banyamulenge, who are Congolese Tutsis, found themselves in the middle of this anger. Some people saw them as foreigners, even though they lived in Congo for many generations (core.ac.uk).

This history of fear and moving across borders created a cycle of revenge. Each group formed its own small army to protect its people. These militias often fought each other over cows, land, and mining sites. The current M23 rebel group claims they are fighting to protect Tutsis from being wiped out. On the other side, many Congolese believe the M23 is just a tool for Rwanda to steal Congo’s wealth. These old wounds make it very hard for anyone to find a path toward peace (thehindu.com).

Two Major Wars That Shook the Continent

Between 1996 and 2003, the Congo went through two massive wars. These wars were so big that people called them the African World War. Uvira was one of the first cities to fall during the first war in 1996. Because it is right on the border, it is a gateway for foreign armies. Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda have all been involved in the fighting in this region. They often supported different rebel groups to gain control over the land (wikipedia.org).

The second war officially ended with a peace deal in 2003. However, the fighting never truly stopped in the eastern part of the country. Rebel groups just changed their names and moved into the forests. The M23 group first appeared in 2012. They said the government did not keep its promises from a previous peace deal. They were defeated once in 2013, but they came back in 2021 with more power and better weapons than before (sabcnews.com).

By late 2025, the M23 had taken over several important cities. They captured Goma and Bukavu. This left Uvira as one of the last major prizes. The city is important because it sits on Lake Tanganyika. If the rebels control Uvira, they can control the trade and movement of goods in and out of the country. This strategic value is why the Congolese army and its allies are fighting so hard to keep it (news.cn).

The Rise of the Wazalendo Militias

In the recent headlines, you will see a name called the Wazalendo. This is a Swahili word that means “patriots.” These are not official government soldiers. Instead, they are a mix of local community militias. The Congolese government started supporting them in 2023. The goal was to have these local groups help the official army fight the M23 rebels (reliefweb.int).

Many of these fighters come from groups called the Mai-Mai. These groups have existed since the 1990s. They believe in defending their ancestral land from people they consider invaders. However, using these militias is very dangerous. They are often organized by their ethnic backgrounds. This can lead to more fighting between neighbors. It also makes it hard for the government to control what the fighters do in the villages (ecoi.net).

The Wazalendo represent a kind of survival as invention for local people. When the official army failed to protect them, they took up arms themselves. But now, these groups are being used as part of the state’s military strategy. This creates a messy situation where it is hard to tell who is a soldier and who is a civilian. Aid groups worry that these militias might commit human rights abuses against people they think are rebel sympathizers (ground.news).

Cholera Emergency: South Kivu

1,200

Suspected Cases

28

Recent Deaths

53

Deaths in Camps

Data as of January 2026. Hunger and poor sanitation are the primary drivers of this crisis. (the-star.co.ke)

Identity and the Crisis of Citizenship

One of the biggest reasons for the fighting is a law from 1981. This law changed who could be a citizen of Congo. It said that a person’s ancestors had to live in Congo before the year 1885. This was the year that European powers divided Africa at the Berlin Conference. Because of this law, many Kinyarwanda-speaking people lost their rights. This includes the Banyamulenge people (core.ac.uk).

When people lose their citizenship, they lose their right to own land and vote. They become “stateless” in the place where they were born. This created a deep feeling of injustice. The M23 rebels often use this issue to gain support. They say they are fighting for the rights of these “persecuted minorities.” They want the government to recognize them as full citizens with all the same protections as other groups (thehindu.com).

On the other side, “indigenous” groups use this law to argue that Tutsis do not belong in Congo. They claim that these groups are foreigners who want to take over the country. This argument is called “Congolité.” It is a dangerous idea that has led to many deaths. In the hills around Uvira, militias often steal cattle and burn villages based on these ethnic labels. These kinship networks are often the only protection people have in a place where the law does not work for everyone.

The Battle for Mineral Wealth and Port Access

While identity is a big part of the war, money is also a factor. Eastern Congo is incredibly rich in minerals like gold, tin, and tantalum. These minerals are needed for smartphones and car batteries. Uvira is a strategic location for moving these minerals. It is known as the “gateway” to the Katanga region. Katanga is where most of the world’s cobalt and copper come from (news.cn).

Control over Uvira means control over the N5 highway. This road is the main path for trucks carrying minerals to international markets. If a rebel group holds this city, they can tax every truck that passes through. They can also use the port on Lake Tanganyika to move goods to other countries like Burundi and Tanzania. This makes Uvira a very valuable prize for any army (sabcnews.com).

The government claims the M23 withdrawal from Uvira is a “disinformation tactic.” They believe the rebels want to look peaceful while still keeping control of the secret trade routes. President Donald Trump and his administration are watching this closely. The United States needs these minerals for green energy technology. If the region stays in chaos, it disrupts the global supply chain. This is one reason why the U.S. has been trying to broker peace deals between Congo and Rwanda (ground.news).

The Catastrophic Toll on Families and Children

The most heartbreaking part of the Uvira conflict is what it does to children. Over 1,000 schools in South Kivu have been forced to close. This has left almost 390,000 students without a place to learn. When schools close, children are more likely to be recruited into militias. They lose their chance for a better future and become trapped in the cycle of violence (reliefweb.int).

Disease is also a major threat. Because so many people are crowded into small areas, illnesses spread fast. A cholera outbreak has been reported in the first half of January 2026. There are already 1,200 suspected cases. People do not have clean water or enough food. This leads to anemia and malnutrition, which makes it even harder to fight off the cholera. At least 53 refugees died in camps in Burundi during the first weeks of the year (the-star.co.ke).

Women and girls face even more dangers. Sexual violence is being used as a weapon by many different groups. When families flee their homes, women are often targeted while they look for food or water. In the displacement camps, some women are forced to trade sex for food. This is a tragedy that leaves deep scars on the community. These families are showing incredible strength, but they are being pushed to their limits (reliefweb.int).

The Education Crisis in South Kivu

1,000+ Schools Closed

Fighting has displaced 390,000 students, stealing their opportunity to learn. (reliefweb.int)

Diplomatic Efforts and the Washington Accords

The international community is trying to stop the fighting through diplomacy. One of the main efforts is the “Washington Accords.” These are truces mediated by the United States. The goal is to create “humanitarian truces” so that aid can reach the people who are suffering. These deals also try to get Congo and Rwanda to talk to each other instead of fighting through proxy groups (ground.news).

There is also the “Doha Process” in Qatar. These meetings bring together regional leaders to find a way to end the war. They focus on things like sending home foreign fighters and securing the borders. However, these peace talks often fail because there is no way to enforce them. Both the government and the rebels often accuse each other of breaking the rules within days of signing an agreement (china.org.cn).

The Congolese government refuses to talk directly to the M23 rebels. They call the rebels “terrorists” and say they will only talk to Rwanda. This makes the diplomatic process very slow. Meanwhile, the people on the ground do not see much change. They continue to see soldiers moving through their fields and hear the sound of gunfire in the mountains. Peace remains a distant dream for the families of Uvira (news.cn).

Conclusion: The Long Road Ahead

The re-entry of Congolese forces into Uvira is a significant moment. It shows that the government is trying to regain control. However, the presence of the Wazalendo militias and the ongoing clashes nearby show that the war is far from over. The history of this region is filled with stories of groups taking and losing ground. Real peace will require more than just soldiers moving in and out of cities (plenglish.com).

The roots of the conflict must be addressed. This includes fixing the citizenship laws and ensuring that all ethnic groups feel safe in their own country. It also means finding a way to share the wealth of the land fairly. Until these deep issues are solved, the cycle of violence is likely to continue. The world must not look away from the suffering in South Kivu. The lives of millions of people depend on a solution that goes beyond the headlines (reliefweb.int).

As displacement rises, the international community must step up its support. Food, medicine, and clean water are needed immediately. But more than that, there needs to be a real commitment to justice. The families fleeing with their livestock and bags deserve a home where they do not have to live in fear. The history of Uvira is a heavy one, but it does not have to be the future for the next generation.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.