Why NC A&T Students Are Turning Campus Energy Into Civics Muscle

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

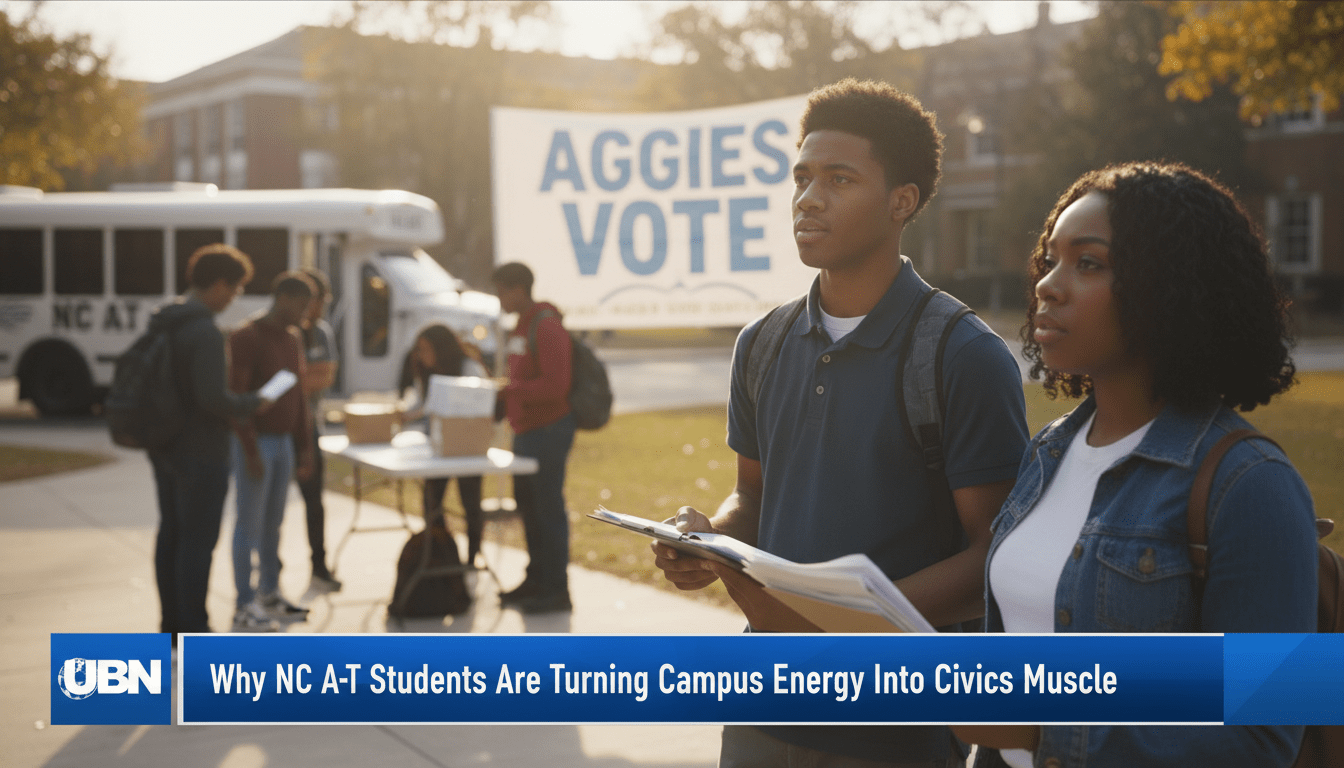

The students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University carry a heavy weight on their shoulders. This weight is not just from textbooks or exams. It comes from a long history of standing up for what is right. Today, a new generation of students is showing that they have the same strength as those who came before them. They are moving beyond the classroom to protect their right to vote. This movement is a response to recent changes that make it harder for students to cast their ballots on campus.

History shows that the fight for the ballot is never truly over for Black Americans. The struggle changes shape, but the goal remains the same. Students at NC A&T are currently facing a situation where their campus early voting site was removed. This happened right before a primary election that falls during their spring break. Instead of giving up, these young leaders are organizing shuttles and carpools. They are turning their frustration into a powerful tool for civic change. This is the story of how a university’s past is fueling its present fight for the future.

The Legacy of the Greensboro Four and Student Power

The spirit of activism at NC A&T started decades ago. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen took a seat at a whites-only lunch counter in Greensboro. These young men are known as the Greensboro Four. Their peaceful protest started a movement that spread across the country. It showed the world that students could be the spark for massive social change (studentsofhistory.com). This act of bravery led to the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC. This group became the leading voice for young people during the Civil Rights Movement (cbcfinc.org).

The Greensboro sit-ins did not happen by accident. They were planned with great care. Students at Bennett College, a nearby school for Black women, played a major role in the strategy. These women, known as the Bennett Belles, worked alongside the NC A&T students to organize the protests (wikipedia.org). This history of collaboration is still alive today. It reminds us that Black students have always had to build their own systems of support. Understanding this troubling history of black voter disenfranchisement helps us see why students are so protective of their rights now.

SNCC focused on organizing communities at the grassroots level. They did not wait for leaders in Washington to act. Instead, they went into rural areas to register Black voters who faced threats and violence (studentsofhistory.com). This “bottom-up” approach is exactly what we see on campus today. Students are not waiting for the Board of Elections to change its mind. They are taking the wheel themselves. They believe that if the system creates a barrier, they must build a bridge over it.

HBCU Voting Proximity Barriers

Percentage of HBCUs within 0.5 miles of a polling site

North Carolina (13%)

Georgia (57%)

A History of Resistance and State Crackdowns

The fight for justice at NC A&T has not always been peaceful because the response from the state was often violent. In 1969, a major uprising took place on campus. It started because a Black student leader at a local high school was denied his rightful election victory. NC A&T students joined the protest to support him. The situation escalated when the National Guard was called in. They used tanks and helicopters to storm the campus dorms. It was one of the most violent attacks on a university in American history (wikipedia.org).

During this event, a student named Willie Grimes was shot and killed. No one was ever held responsible for his death. The state claimed they were restoring order, but a later report found their actions were reckless (wikipedia.org). This painful memory is part of the university’s identity. It teaches students that their political power is often seen as a threat. They know that when they stand up for their rights, they might face a strong pushback from those in power.

Even though the tactics have changed, the feeling of being targeted remains. Instead of tanks, students now face administrative hurdles and district maps that split their campus. This resistance to student voices is a recurring theme in North Carolina history. The success of African American students depends on their ability to navigate these systemic challenges. The 1969 uprising proved that Aggies will not be silenced, even when the odds are stacked against them.

The Battle Over Redistricting and Racial Gerrymandering

In more recent years, the struggle has moved into the courtroom. In 2016, the North Carolina legislature redrew the maps for congressional districts. They split the NC A&T campus right down the middle. One half of the campus was in District 6, and the other half was in District 13 (commoncause.org). This is a tactic called “cracking.” It spreads a group of voters across multiple districts so they cannot have a majority in any of them. It effectively waters down the power of the student vote.

Students responded with a campaign called “Real Aggies Vote.” They argued that splitting a small campus into two districts made no sense unless the goal was to silence them. Courts later ruled that this map was an unconstitutional “racial gerrymander” (commoncause.org). The legislature was forced to fix the map, but the message was clear. There are people in power who view the concentrated voting strength of Black college students as something to be dismantled.

This kind of political maneuvering creates confusion for young voters. Imagine living in a dorm and having to go to a different polling place than your friend across the street. It makes the simple act of voting feel like a complicated puzzle. Despite these tricks, the students stayed focused. Their work helped restore a more fair map for their community. However, as the 2026 election cycle shows, new challenges are always appearing on the horizon.

NC A&T Student Turnout Over Time

The 2026 Voting Site Crisis and Party-Line Politics

As the 2026 Primary Election approaches, a new obstacle has emerged. The Guilford County Board of Elections voted to remove the early voting site from the NC A&T campus. This site had been available for many years. The decision was made in a 3–2 vote that fell exactly along party lines (carolinapublicpress.org). Under the current political climate, with President Donald Trump in office, partisan tension is at an all-time high. Republican members of the board argued that the site had low turnout, but students strongly disagree.

The timing of this change is particularly difficult. The 2026 primary falls during the university’s spring break. This means many students will be away from campus on the actual day of the election. Early voting was the only time they could cast their ballots at their campus precinct before leaving for the break (wfdd.org). Without an on-campus site, they must travel to off-campus locations. For many students who do not have cars, this is a major hurdle.

The North Carolina State Board of Elections also upheld this decision in another 3–2 party-line vote. The board members who voted to remove the site pointed to a turnout of about 800 students in a previous cycle as a reason to cut costs (wfdd.org). However, activists point out that rural sites with even fewer voters are often kept open. They believe that the real reason for the removal is to decrease the influence of the student vote. This shift in the political narrative shows how administrative rules can be used as weapons in an election year.

Defining the Modern-Day Poll Tax

Student organizers are calling the removal of the voting site a “modern-day poll tax.” To understand this, we must look at history. A poll tax was a fee that people had to pay before they were allowed to vote. It was used in the Jim Crow South to prevent Black people from exercising their rights (nmcdn.io). The 24th Amendment to the Constitution eventually banned these taxes because they made voting a privilege for the wealthy (cbcfinc.org).

Today, students argue that taking away a campus site is like a tax on their time and money. If a student has to pay for an Uber or take two buses to reach a polling place, that is a financial barrier. If they have to miss work or class to travel miles away, that is a cost they must pay to vote (fairelectionscenter.org). This is why the term “logistical tax” is becoming more common. It describes how the system can make voting so inconvenient that many people simply give up.

These barriers are not equal across the state. Research shows that only 13% of HBCUs in North Carolina have a polling site within walking distance. In other states like Georgia, that number is over 50% (fairelectionscenter.org). This shows that the lack of access in North Carolina is a specific choice made by local officials. It reminds us of a time when newly emancipated Black people continued to face involuntary servitude and other forms of control. The struggle for full citizenship is still being fought through the lens of accessibility.

Turning Outrage Into “Civics Muscle”

Instead of being discouraged, NC A&T students are taking action. Two juniors, Terrence Olu Rouse and Shia Rozier, started the “Protect Ours” movement. Their goal is to “take the wheel” on early voting. They realize that they cannot rely on the government to make voting easy for them. They have organized a fleet of shuttles and carpools to take students to the nearest off-campus voting sites (wfdd.org). This effort mirrors the “Freedom Rides” of the past, where people traveled long distances to challenge segregation.

The movement is about more than just rides. It is about building a culture of civic engagement. Hundreds of students have attended Board of Elections meetings to make their voices heard. When the board voted to remove the site, the students stood in the room in total silence. They held signs to show their disapproval (wfdd.org). This silent protest is a tactic that has been used by activists for over a hundred years. It is a powerful way to show strength without saying a single word.

The student response has been very effective. In the 2020 election, over 91% of Aggies were registered to vote. Even with the hurdles, 71% of those registered managed to cast their ballots (technicianonline.com). This shows that the “civics muscle” on campus is real. When students are told they cannot do something, they work twice as hard to get it done. Their resilience is a direct legacy of the Greensboro Four.

NC A&T Student Voter Power (2025)

Total ballots cast by students in 2025 General Election

The Importance of the Primary and the 0.5-Mile Benchmark

Many people focus only on the presidential election in November. However, students know that primary elections are just as important. In many parts of North Carolina, the districts are drawn so that one party always wins the general election. This means the primary is the only time voters have a real choice in who represents them. If students are blocked from the primary because of spring break and site removals, they lose their only chance to pick their leaders (democracydocket.com).

Proximity to a polling place is a key factor in turnout. Experts use a “0.5-mile benchmark” to measure accessibility. If a polling site is within half a mile, a student can walk there between classes. If it is further away, it requires a car or public transit. Since many freshmen are not allowed to have cars on campus, they are entirely dependent on having a site nearby (fairelectionscenter.org). Removing the campus site effectively places a “transportation tax” on the youngest voters.

Despite these systemic barriers, the students at NC A&T continue to lead the way. They are proving that a university is more than just a place to get a degree. It is a place to build political agency. They are carrying on a tradition that started at a lunch counter in 1960. By organizing rides and staying informed, they are ensuring that their voices will be heard in 2026 and beyond. The “civics muscle” they are building today will strengthen their community for generations to come.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.