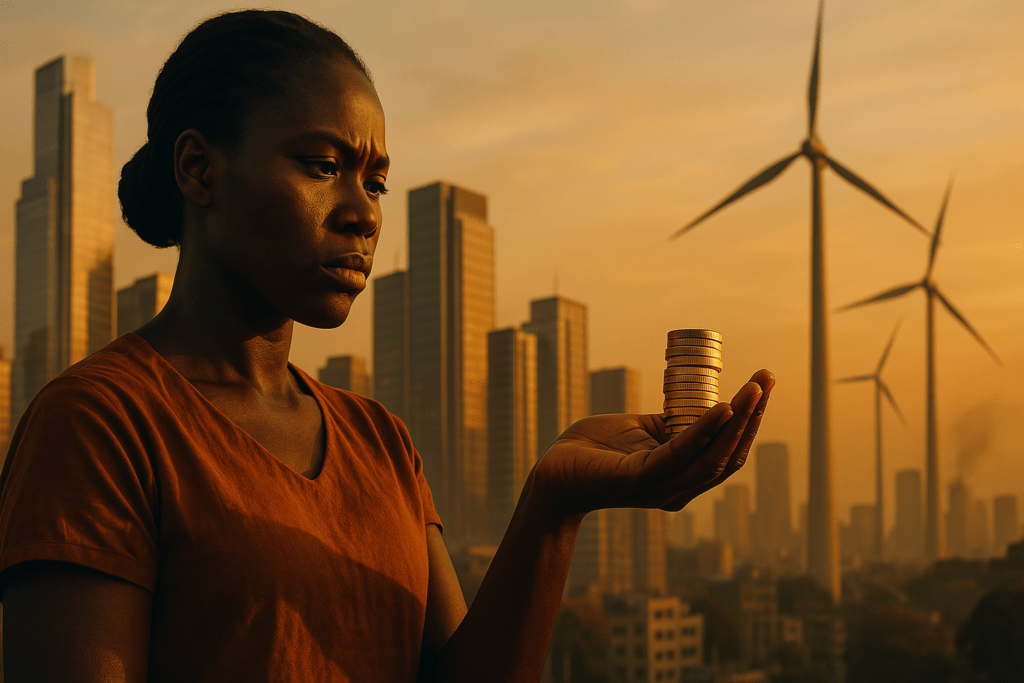

Climate Debt: Fueling Africa’s Sustainable Urban Future

Africa’s Climate Debt: A Path to Justice & Growth

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Wealthy, industrialized nations owe the continent of Africa a staggering $36 trillion because of the climate crisis. This isn’t just some abstract number; it’s a debt rooted in history, calculated based on the pollution pumped out over decades. This pollution disproportionately harms Africa, a continent that has contributed minimally to the problem but suffers intensely from its effects. ActionAid reports released in early 2025 laid bare this reality, highlighting a profound global injustice (Voice of Gambia).

This massive climate debt dwarfs the continent’s foreign debt burden. Think about that: Africa is owed far more than it owes. Recognizing this disparity isn’t just about fairness; it’s about understanding the constraints on African development. Furthermore, it opens conversations about how rectifying this imbalance could unlock resources needed for critical progress across the continent.

The Scale of Climate Debt Africa Owes

The $36 trillion figure represents climate reparations owed to Africa by rich countries. This debt stems directly from their historical greenhouse gas emissions and ongoing failure to adequately address the severe climate impacts hitting the continent (Voice of Gambia). To put this in perspective, Africa’s total foreign debt is about $1.45 trillion. That means the climate debt owed *to* Africa is roughly 70 times larger than the financial debt Africa owes *to* others (Voice of Gambia; Africa Brief; ActionAid).

Consider the immediate financial pressures. In 2024 alone, lower-income African countries paid out $60 billion just to service their foreign debts (Africa Brief). Imagine what that money could do if invested domestically – funding healthcare, expanding education, or building resilience against climate change. Meanwhile, estimates suggest rich nations *should* be providing $1.4 trillion *annually* in climate finance to support vulnerable countries. That’s 25 times more than what African nations are currently paying out in debt repayments each year (Voice of Gambia; Africa Brief). Clearly, the flow of funds needs a serious reversal.

Africa’s Debt Reality: Climate vs. Foreign

Calculating Historical Climate Debt Obligations

So, how is this “climate debt” calculated? It’s not arbitrary. Methodologies compare a country’s historical emissions against what would be considered its fair share of the remaining global carbon budget – the amount of CO2 we can still emit while trying to limit catastrophic warming. Essentially, it measures the overuse of our shared atmosphere. A typical formula subtracts a country’s population-based share of a sustainable emissions budget from its cumulative emissions over time (Calculating Climate Debt. A Proposal).

Different models exist, like those prioritizing historical emissions and per capita fairness. Still, they rely on assumptions, such as the total sustainable global emissions level (e.g., 9 GtCO2 vs. 3 GtCO2 annually), which impacts the final debt figures (Calculating Climate Debt. A Proposal). Then, to put a price tag on this “emissions debt,” analysts use monetary valuation, often based on carbon pricing. This translates the excess tons of CO2 into a financial obligation, reflecting either the cost of climate damages or the cost of decarbonization needed to compensate (Institut Avant Garde). Ultimately, this process aims to quantify the responsibility of high-emitting nations.

This concept naturally leads to discussions about “Climate Reparations.” Unlike traditional loans, reparations aren’t about repaying borrowed money. Instead, they address the violation of “equitable rights” to atmospheric resources (Calculating Climate Debt. A Proposal (Paredis models)). When wealthy, industrialized countries emitted far beyond their fair share, they effectively used up the atmospheric space that should have been available to others, primarily nations in the Global South. Therefore, reparations involve compensation – financial transfers, technology sharing – for the harm caused by this historical overuse, rooted in principles of justice and equity (Institut Avant Garde).

The Predatory Cycle of the African Debt Crisis

Compounding the injustice of climate debt is the reality of conventional foreign debt. African nations often face exploitative interest rates when they borrow money on the international market. The average interest rate African countries pay is a staggering 9.8%. Compare that to a wealthy nation like Germany, which pays around 0.8% (ActionAid). This vast difference isn’t accidental; it reflects a financial system often described as predatory, trapping nations in cycles of debt and stifling sustainable development (ActionAid).

This leads to crippling “Debt Servicing” burdens. Debt servicing means making the required payments on a loan – both the principal amount borrowed and the accumulated interest. When interest rates are high, servicing the debt consumes a considerable portion of a country’s budget. Consequently, this forces governments to prioritize paying back lenders over investing in their own people and critical public services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure (Economic Policy Institute). It’s a vicious cycle where debt hinders the very development needed to escape it.

Debt’s Toll on Women, Girls, and Vital Services

The consequences of high debt burdens fall heaviest on the most vulnerable populations, particularly women and girls. When governments are forced to cut spending to meet debt obligations – often under conditions imposed by international financial institutions like the IMF – social programs are frequently the first on the chopping block. Investments crucial for gender equity, such as targeted health programs, education access, and support services, are undermined (Climate Action Network International). Women often bear the brunt of these austerity measures, taking on more unpaid care work as public services shrink.

Malawi offers a stark illustration of this devastating dynamic. The country is owed an estimated $750 billion in climate debt due to historical emissions from wealthy nations. Yet, its actual foreign debt is around $3.5 billion – more than 200 times smaller (AfricaBrief). Despite this massive imbalance, Malawi spends nearly 30% of its national budget servicing its relatively small foreign debt. This severely cripples funding for essential sectors like agriculture, healthcare, and education, perpetuating cycles of poverty and hindering climate adaptation efforts (AfricaBrief). It highlights the absurdity of a system where victims of climate change are paying creditors instead of investing in solutions.

Malawi: A Case of Debt Injustice

Climate Finance for African Cities: A Potential Path?

This brings us to a critical question: How could addressing climate debt potentially fuel sustainable development, particularly in Africa’s rapidly growing cities? The available information highlights the immense scale of climate debt owed and the crippling impact of current foreign debt servicing (Voice of Gambia; Africa Brief). While the provided sources focus primarily on calculating the debt and its broader economic impacts, they don’t explicitly detail mechanisms linking climate debt *repayment* directly to funding *urban* development projects.

However, the logic is compelling. If the $36 trillion climate debt were acknowledged and mechanisms for reparations or substantial climate finance were established, it could free up vast resources. Instead of African nations sending $60 billion annually out of the continent for debt servicing (Africa Brief), these funds could be redirected domestically, potentially supplemented by climate reparation payments. Consequently, this capital could theoretically support crucial investments in sustainable urban infrastructure – clean energy, public transport, resilient housing, waste management, and green spaces – essential for managing urbanization sustainably and adapting to climate change impacts. The potential is enormous, even if current frameworks haven’t solidified this specific link.

Distinguishing Foreign and Climate Debt Africa

Understanding the fundamental difference between “climate debt” and “foreign debt.” Foreign debt arises from contractual financial agreements—loans taken out, often with interest, that must be repaid according to agreed-upon terms. It’s a standard financial liability governed by market principles. Climate debt, conversely, is framed as a moral, ethical, and potentially legal obligation stemming from environmental injustice (Calculating Climate Debt. A Proposal).

Climate debt arises from the historical and ongoing overuse of the global atmospheric commons by wealthy, industrialized nations (often termed the Global North). Their excess emissions have caused biophysical harm and limited the developmental space for nations (mainly in the Global South) that emitted far less (Calculating Climate Debt. A Proposal). Therefore, the monetary valuation assigned to climate debt reflects compensation for this harm or the cost of necessary climate action, emphasizing equity rather than profit-driven lending (Institut Avant Garde). Recognizing this distinction is vital for pushing climate justice claims forward.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.