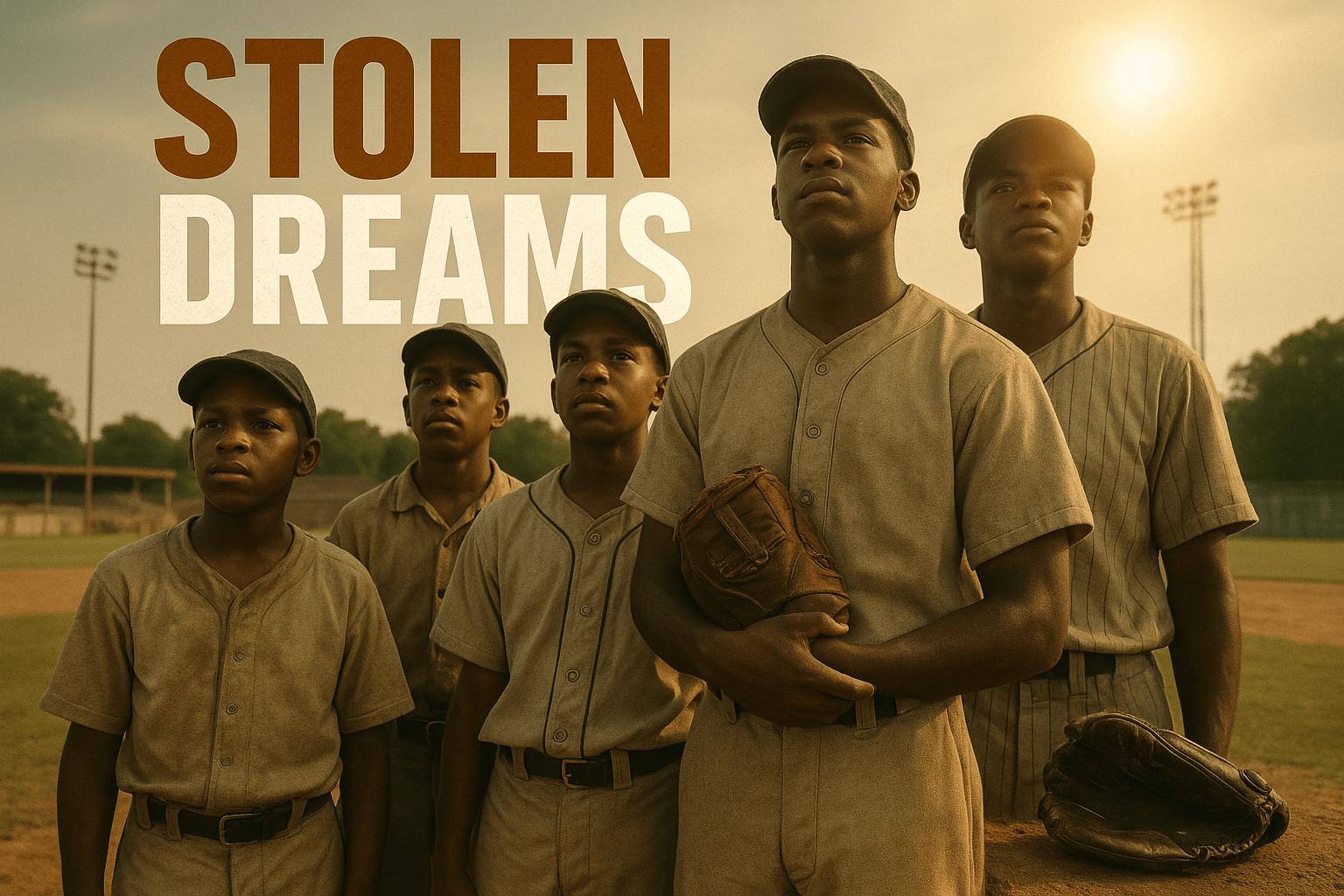

1955 Cannon Street All-Stars: Stolen Dreams

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

The Forfeit That Changed History

In 1955, the Cannon Street YMCA All-Stars, an all-Black Little League team from Charleston, South Carolina, found their dreams shattered by racial discrimination. This team, representing the first African American Little League in South Carolina’s history (baseballhall.org), faced an uphill battle from the moment they registered for the Charleston city tournament in July 1955. All the white teams withdrew, leaving the Cannon Street team to win by forfeit (washingtonpost.com). This seemingly innocuous victory became the pretext for their exclusion from the regional tournament.

Little League officials ruled the team ineligible because they had advanced by forfeit, not by playing and winning (theconversation.com). This decision was made despite Little League Baseball officially prohibiting racial discrimination (theconversation.com). The rule requiring teams to advance by playing and winning, rather than by forfeit, was a standard Little League regulation. However, in the case of the Cannon Street All-Stars, this rule was used as a pretext to prevent their advancement, highlighting a racial motivation rather than a strict adherence to procedure. Little League President John McGovern initially tried to justify the ruling by stating that teams needed to win games on the field to move on to regional play, which officially ended the Cannon Street All-Stars’ season (baseballhall.org). The public outcry and criticism from figures like baseball writer Dick Young, who called for McGovern’s resignation due to his failure to enforce the organization’s ban against racial discrimination, suggest that the rule was applied selectively (baseballhall.org). The South Carolina Little League chose to disband entirely rather than allow the Cannon Street team to play (washingtonpost.com).

Jim Crow and Segregation’s Grip

The experience of the Cannon Street All-Stars is a stark illustration of the pervasive Jim Crow laws and state-sanctioned segregation that defined the American South in the 1950s. These laws enforced racial segregation and discrimination in nearly all aspects of life, including public facilities, education, and even youth sports. They were designed to maintain white supremacy and subjugate African Americans, creating a deeply unequal society. The white teams’ withdrawal from playing the Cannon Street All-Stars was a direct result of this racial prejudice and the prevailing segregationist attitudes in South Carolina at the time (washingtonpost.com). The South Carolina Little League state director actively encouraged all 61 all-white all-star teams in the state to refuse to play the Cannon Street team (postandcourier.com). This widespread refusal ultimately led to the South Carolina Little League choosing to disband rather than allow the Black team to compete, clearly demonstrating that the motivation was to avoid integration (washingtonpost.com).

This occurred despite the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in *Brown v. Board of Education*, which declared segregation in schools unconstitutional (theconversation.com), highlighting the ongoing resistance to integration. The Charleston News and Courier’s editorial, “Agitation and Hate,” further highlights the racial tensions and the societal resistance to racial integration that underpinned these withdrawals (washingtonpost.com).

The Rise of Segregated Leagues

The discrimination against the Cannon Street All-Stars did not end with their exclusion from the Little League World Series; it catalyzed the formation of segregated baseball leagues across the South. Danny Jones, the state’s director of Little League Baseball, resigned and created the Little Boys League, which explicitly prohibited Black players (theconversation.com). This new league’s charter specifically called for it to be segregated (postandcourier.com).

The Little Boys League was later rebranded as Dixie Youth Baseball and quickly replaced Little League in many Southern states, eventually spanning most of the former Confederacy (theconversation.com). Within six years of its formation, there were 390 Dixie Youth Baseball leagues (theconversation.com). Augustus Holt, the Cannon Street team’s historian, refused to allow his son to play in Dixie Youth Baseball due to its association with segregation, noting a Confederate flag on its rulebook (patriotspoint.org). These leagues operated by excluding Black players, reinforcing the racial hierarchy prevalent in the Jim Crow South, in stark contrast to Little League Baseball’s stated prohibition against racial discrimination.

A Bittersweet Invitation

Despite being denied the opportunity to play, the Cannon Street All-Stars received a bittersweet invitation: to attend the 1955 Little League World Series championship game. Little League’s president, Peter McGovern, invited the team to be guests for the championship game after widespread criticism (theconversation.com). The team was introduced before the game, and players recall hearing shouts of “Let them play!” from the bleachers (theconversation.com, theworld.org). John Rivers, who played second base for the team, told a reporter he can still “hear it now.”

A photograph from the day reveals the profound disappointment on the players’ faces as they watched other boys play (theconversation.com, theworld.org). As one player, Bailey, stated, “We were the only team in the history of the Little League baseball that never got a chance to play. It was hard to swallow” (washingtonpost.com). This sentiment underscores the profound disappointment and injustice felt by the young athletes who were denied the opportunity to compete due to racial discrimination. The experience of being systematically excluded and having their dreams crushed at such a young age undoubtedly left emotional scars, shaping their understanding of fairness and racial dynamics in America.

A Reflection of Broader Struggles

The experience of the Cannon Street All-Stars highlights the broader racial tensions and civil rights struggles of the 1950s. The team’s journey to Williamsport occurred on the same day, August 28, 1955, that Emmett Till was brutally murdered in Money, Mississippi (theconversation.com, theworld.org). Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American boy, was brutally lynched for allegedly whistling at a white woman. His horrific murder and his mother’s decision to have an open-casket funeral brought the brutality of racial violence in the South to national attention, becoming a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights Movement. This chilling coincidence underscores the dangerous and racially charged atmosphere in which the Cannon Street team was navigating.

The story of the Cannon Street All-Stars broke through the silence of many white-owned newspapers on racial discrimination (theconversation.com). Jackie Robinson, who broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier, expressed his dismay at the white teams’ refusal to play them, stating, “How stupid can they be?” (theconversation.com). His reaction further emphasized the absurdity and injustice of the situation. The incident served as a microcosm of the larger fight for civil rights, where even children’s sports became a battleground for racial equality.

Their Enduring Legacy

The legacy of the Cannon Street All-Stars continues to be recognized and remembered. The story of the Cannon Street All-Stars is included in an exhibit on Black baseball at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, which opened in 2024 (baseballhall.org). Surviving members of the team, now in their early 80s, were scheduled to be recognized before the Little League World Series championship game on August 24, 2025, 70 years after their initial experience (theconversation.com).

John Rivers, a former player, became a successful architect and emphasizes the tragedy of having dreams taken away from a youngster (theconversation.com). Augustus Holt, the team’s historian, played a crucial role in bringing Little League back to peninsular Charleston after a 40-year absence, demonstrating a direct positive change rooted in the team’s story (patriotspoint.org). The team’s story is also shared through symposiums, with many attendees, including school groups, learning about their perseverance and lasting impact on society for the first time (patriotspoint.org). These ongoing efforts ensure that their story remains a vital part of American history, reminding us of the struggles for equality and the enduring power of resilience.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.