Chicago Council Members Reject Slavery Apology: How History Explains Today’s Reparations Fight

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Four Council Members Say No to History: Chicago’s Reparations Vote Exposes Deep Divisions

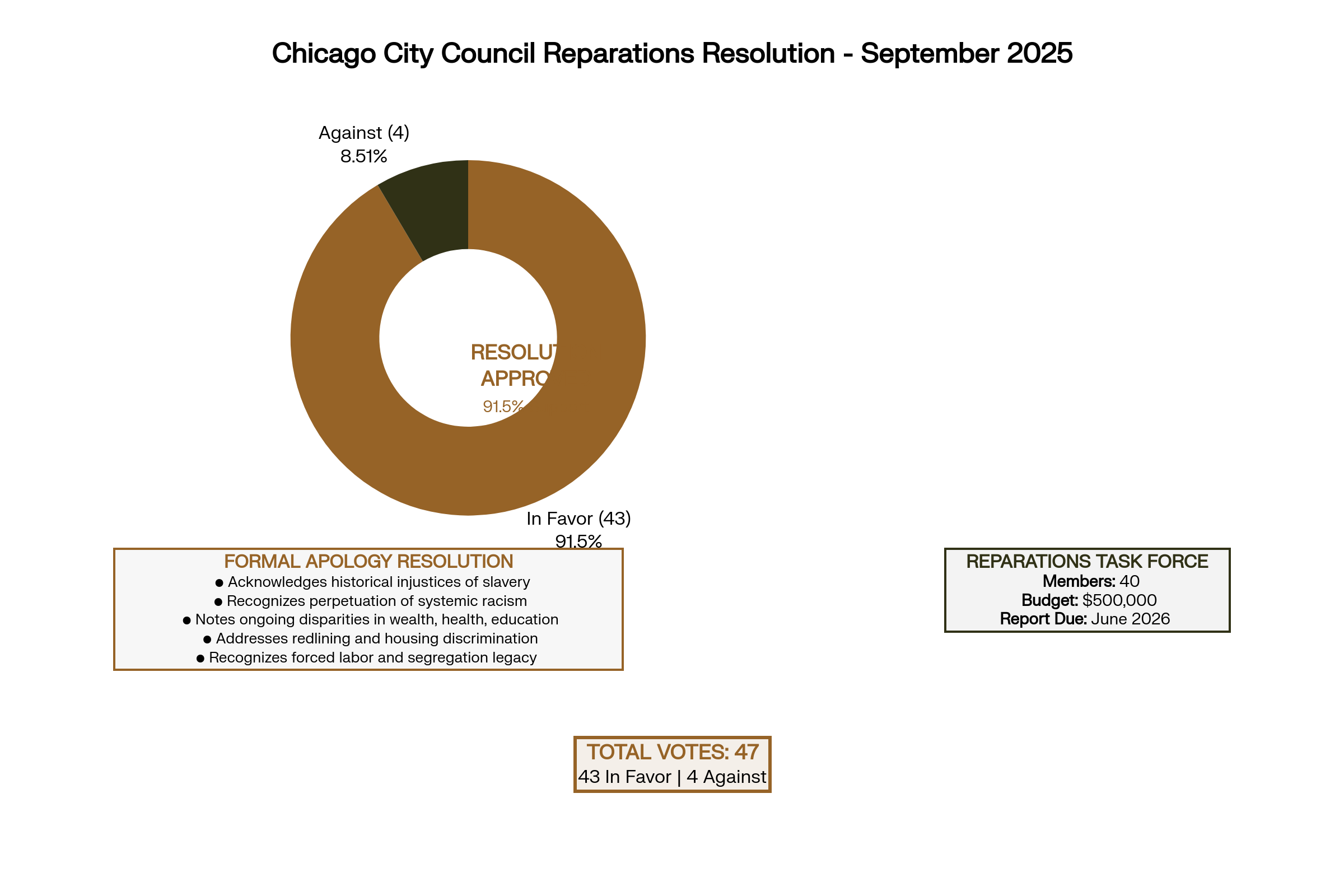

In September 2025, Chicago’s City Council overwhelmingly approved a historic resolution apologizing for slavery, segregation, and systemic racism affecting Black residents. The vote stood 43-4 in favor. Yet four aldermen rejected a simple apology, igniting fury from Black council members and exposing how Americans still debate whether Black people deserve acknowledgment for centuries of documented harm.

This moment matters because it shows how the fight for reparations remains deeply contested in America’s third-largest city. Meanwhile, elsewhere (Atlanta Black Star), Mayor Brandon Johnson pushed the city toward a comprehensive reparations agenda to address “decades of oppression and historic disinvestment.” The four dissenting votes tell us something critical about who still refuses to acknowledge the documented harms that built modern Chicago.

The Apology That Four Council Members Could Not Accept

Alderman Lamont Robinson, who sponsored the resolution, verbally confronted his colleagues after the vote. According to reporting from (Atlanta Black Star), Robinson declared: “Shame on you!” He demanded that the four no voters explain their position to their Black constituents across the city’s 50 wards. The tension in chambers reflected a deeper national argument about America’s debt to Black people.

What did the resolution actually do? It issued a formal apology from City Council to Black Chicagoans for “the historical injustices of slavery, segregation, systemic racism and the policies that have perpetuated racial inequality” (Atlanta Black Star). The resolution acknowledged that after Illinois became a “free state” in 1818, its laws subjected free Black residents to oppressive restrictions including denial of voting rights, prohibitions against gathering in groups, and bans on bearing arms. It documented how Black Chicagoans continued facing discrimination through forced labor, segregation, redlining, housing discrimination and systemic inequities that persist today.

For Alderman Maria Hadden, the four no votes were “shocking” and “appalling” (Atlanta Black Star). She expected this to pass unanimously. Instead, she witnessed what political observers saw as historical revisionism in real time.

Why They Voted No: Denying Chicago’s Connection to Slavery and Harm

Nick Sposato, a white Trump supporter, did not mince words about his refusal. He stated flatly: “I apologize to absolutely nobody. I want my name off there. I do not want to be associated with this” (Atlanta Black Star). Sposato claimed there was “a lot of blame to go around, but certainly not in the city of Chicago, certainly not my family.” His response exemplifies how some white Americans reject accountability even for systemic policies their families benefited from.

Alderman Raymond Lopez offered a different argument. He claimed Chicago’s economy was not slave-driven and that the city actually served as a haven for freed enslaved people escaping Southern slavery (Atlanta Black Star). Lopez noted that roughly half a million people participated in the Great Migration to Chicago. He suggested the council should focus on contemporary failures rather than historical ones. This argument ignores documented proof that the wealth flowing into Chicago came from systems that excluded Black residents.

Alderman Anthony Napolitano presented a provocative twist. He voted no because he claimed the apology rang hollow coming from an administration that had, in his view, abandoned historically Black neighborhoods. Napolitano pointed out that over six hundred million dollars had been spent on migrant services while the same city government diverted hundreds of millions from Black neighborhoods (Atlanta Black Star). While this criticism about current spending priorities contains validity, using it to reject an apology for slavery represents a political deflection. Both historical reparations and current disinvestment are separate failures.

James Gardiner cast his vote against the resolution without public explanation, according to records.

Chicago’s Own Slavery: The History Algunos Council Members Wanted to Deny

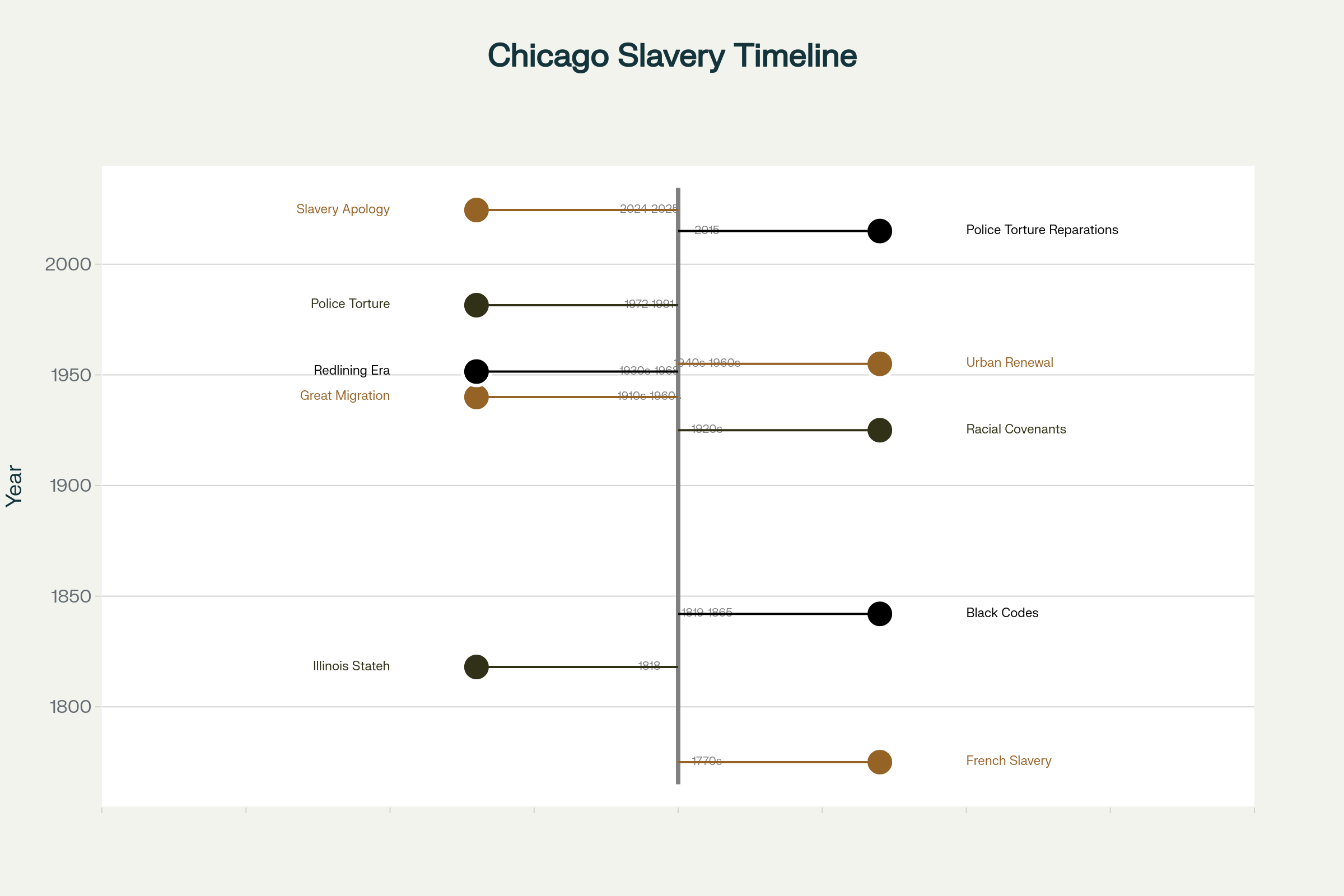

The uncomfortable truth that Alderman Sposato and Lopez avoided: slavery existed in Chicago and shaped the city’s growth. When French traders established Chicago in the 1700s, they brought enslaved African and Native American people. Records show Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, Chicago’s first permanent settler, used enslaved laborers at his trading post along the Chicago River. John Kinzie, a major figure in early Chicago, purchased enslaved individuals, as documented in transaction records.

After the Northwest Ordinance supposedly banned slavery in 1787, the practice persisted through deliberate legal maneuvering. When Illinois joined the Union as a “free state” in 1818, its constitution contained loopholes. Slavery officially ended, but indentured servitude continued, particularly in southern Illinois salt mines. Between 1819 and 1865, Illinois Black Codes reinforced slavery’s structure through different means. These laws required Black residents to carry “certificates of freedom” or face arrest and potential re-enslavement. Black people could not vote, testify against whites in court, serve on juries, gather in groups of three or more, or bear arms (WTTW).

Chicago was not some abolitionist paradise, despite being located in a “free state.” Rather, it became a hub for the Underground Railroad precisely because slavery’s threat remained real. Organizations like Quinn Chapel AME Church, founded in 1847, operated safe houses for escaping enslaved people fleeing federal marshals enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The fact that Chicago needed an underground railroad proves that freedom was fragile and never guaranteed for Black people.

The Great Migration Trap: Movement Without Liberation

Alderman Lopez referenced the Great Migration as evidence Chicago welcomed Black people and therefore bore no responsibility for slavery’s legacy. This misunderstands the profound harm Chicago inflicted on arriving Black migrants. Beginning around 1910, over 850,000 Black Southerners migrated north seeking economic opportunity and escape from Jim Crow violence (Chicago Reporter). What they encountered in Chicago was a different but equally brutal system of segregation.

By the 1920s, Chicago had weaponized racial covenants as a tool of segregation. These were clauses inserted in property deeds that forbade occupancy by “negroes” or limited homes to members of the “Caucasian race.” At one point, over 80 percent of Chicago properties carried racial covenants. The National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) led this effort, with real estate developers proudly advertising “highly restricted” properties in newspapers like the Chicago Tribune, claiming covenants protected neighborhoods from “undesirable elements” (Chicago Reporter). This language was transparent racism with legal enforcement.

Despite the Supreme Court’s 1917 Buchanan v. Warley ruling against explicit segregation laws, it said nothing about private housing covenants. Developers seized the opportunity. In 1926, the Supreme Court decided it could not prevent these private agreements. Chicago’s white neighborhoods remained white by law, enforced by deed.

Redlining: How Federal Policy Built the Wealth Gap Chicago Still Experiences

Then came the Great Depression and federal intervention that deepened segregation. The Federal Home Loan Bank Board created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) to stabilize housing markets. But HOLC maps became weapons. Appraisers rated neighborhoods on color-coded maps, with “D” ratings (redlined in red) marking areas considered highest risk. Neighborhoods where Black people lived were almost automatically redlined.

The language on these maps was explicitly racist. Descriptions included phrases like “negro encroachment,” “infiltration,” and “inharmonious races.” Bronzeville, the heart of Black Chicago, was described as facing “continued influx of negroes” that would cause “overflow into adjoining sections” that the city was “trying to restrict.” Washington Park was labeled “completely monopolized by the colored race.” These were not coded messages; this was government-sanctioned racism documented in official files.

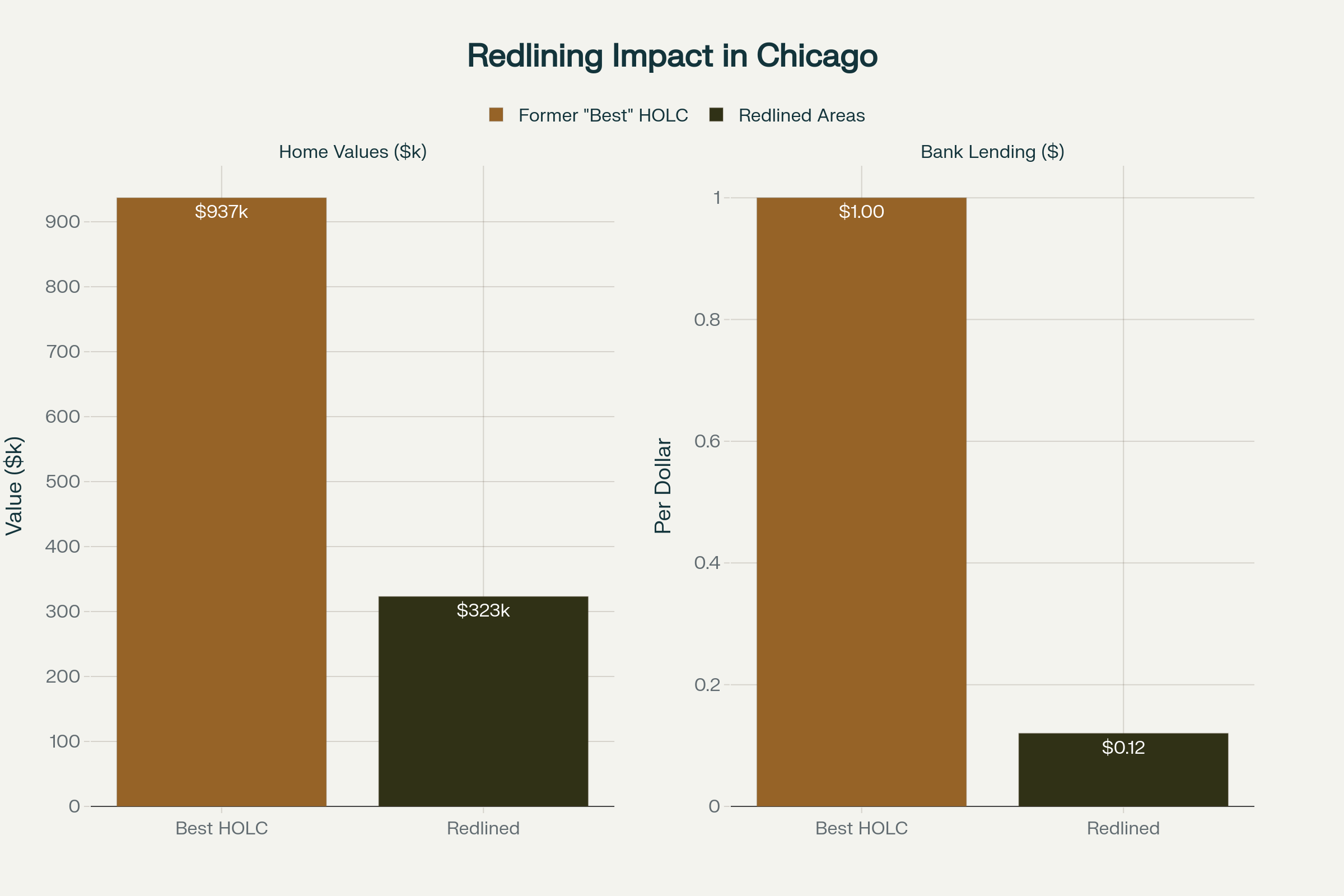

The consequences were devastating. Black homeowners were more reliable at paying mortgages than white homeowners, yet their neighborhoods received lower ratings. Banks and mortgage lenders refused to invest in redlined areas. When Black families could access mortgages, speculators charged them double or triple the market price through exploitative “contract” arrangements where buyers never built equity and risked losing everything on a single missed payment (ACLU). This system extracting wealth from Black families while preventing them from building generational wealth through home ownership.

The numbers tell the story. Homes in formerly “Best” rated HOLC zones now have median values around $937,000. Homes in formerly redlined zones have median values around $323,000 (Chicago Reporter). This gap stems directly from policy choices made ninety years ago. For every dollar banks lend in Chicago’s white neighborhoods, they invest just 12 cents in Black neighborhoods and 13 cents in Latino areas, according to a 2020 WBEZ study (ACLU). The wealth gap is not mysterious or inevitable; it is the designed outcome of deliberate policy.

Urban Renewal and Forced Displacement: Chicago Destroyed Black Neighborhoods Twice

Just when Black Chicagoans began building wealth despite redlining, the city employed another weapon. Urban Renewal legislation in the 1940s and 1950s gave Chicago expanded powers to seize property for “slum clearance” and neighborhood “rehabilitation.” In reality, the city targeted thriving Black neighborhoods. Over a fifteen-year period, more than 80,000 Chicagoans were forcibly displaced, predominantly Black residents.

Institutions like the Illinois Institute of Technology, the University of Chicago, and Mercy Hospital expanded into neighboring communities. Black homeowners’ voices carried no political weight in these decisions. The city targeted neighborhoods redlined in the 1930s and labeled them “blighted,” then demolished them. Residents were relocated to crowded public housing projects, often replacing one Black neighborhood with another, concentrating poverty artificially.

The Dan Ryan Expressway, opened in 1961, literally ran straight through the length of the Black Belt, requiring demolition of Black neighborhoods and forced relocation of residents. Black Chicagoans lost both the neighborhoods their parents had built and the property values that could have passed wealth to future generations. While white suburban neighborhoods developed wealth through property appreciation and mortgage access, Black neighborhoods were demolished and residents warehoused in public housing.

Police Torture and the Precedent for Reparations

Chicago experienced another specific atrocity that became precedent for reparations. From 1972 to 1991, white detectives under Commander Jon Burge tortured over 120 Black suspects, predominantly Black men, to extract false confessions. The torture methods included electrical shocks to genitals, suffocation, beatings, and mock executions. At least 65 known torture survivors remain incarcerated due to forced confessions.

After decades of organizing by torture survivors, families, civil rights lawyers, and community activists, Chicago City Council passed the nation’s first police torture reparations ordinance on May 6, 2015 (ACLU). The $5.5 million package provided up to $100,000 to each torture survivor, free access to City Colleges for survivors and family members, a public memorial, mandatory curriculum teaching the Burge scandal in schools, and a community center for torture victims (Chicago-Kent Law Review).

This precedent proved reparations were achievable in Chicago. It showed that city officials could acknowledge specific harms and provide concrete remedies. The police torture ordinance established that reparations in Chicago meant not just money, but education, healthcare access, and memorial recognition of harm. This became the template for broader reparations efforts.

From Apology to Action: Mayor Johnson’s Reparations Vision

Mayor Brandon Johnson took office committed to moving beyond symbolic gestures. In June 2024, he signed an executive order creating a Reparations Task Force to develop Chicago’s first comprehensive reparations study. Johnson formally apologized “on behalf of the city of Chicago for the historical wrongs committed against Black Chicagoans and their ancestors” (WTTW). This was not just rhetoric; it was the foundation for substantive policy.

The task force comprises 40 members, funded with $500,000 from the city’s 2024 budget. Twenty-five members were appointed by Johnson and the City Council’s Black Caucus, while fifteen spots were reserved for community applications. Members are paid to serve for one year, with a comprehensive report due by June 2026 (WTTW).

The task force is charged with studying the institution and legacy of slavery, Jim Crow Laws, and discriminatory policies affecting Black Chicagoans from slavery through the present. It must identify key areas of harm including housing, policing, incarceration, education, health, and economic development. It must develop recommendations for remedies and restitution for “past injustices and present harm” with a June 2026 deadline (WTTW).

Learning From Evanston: The Model and the Challenges

Chicago is watching Evanston, the nearby suburb that became the first U.S. city to implement a reparations program. In 2019, Evanston set aside $10 million from cannabis sales tax revenue to help Black residents buy homes through mortgage assistance and home improvement funding (CNN). By June 2025, over $5.5 million had been distributed in $25,000 payments to qualifying Black residents (Daily Northwestern).

Yet Evanston’s program now faces a legal challenge that threatens Chicago’s plans. A conservative activist group called Judicial Watch filed a class action lawsuit claiming Evanston’s program violates the equal protection clause because race-based qualifications determine eligibility (Know Your Rights Camp). If the court rules against Evanston, it could prevent Chicago from implementing race-specific reparations. Meanwhile, Evanston’s program faces another problem: lower than expected cannabis sales mean fewer resources than originally budgeted.

Chicago’s Chief Equity Officer Carla Kupe acknowledged these challenges but remained committed. “Because at the end of the day, whatever you call it—DEI, equity—it is all about dignity,” she said (Atlanta Black Star). Johnson declared the administration would not budge, vowing to stay committed despite federal interference.

A Broader National Movement: HR 40 and the Fight for Federal Reparations

Chicago’s reparations effort connects to a larger national movement. In 1989, Representative John Conyers introduced HR 40, legislation creating a commission to study and develop reparations proposals for African Americans descended from enslaved people. The “40” references the unfulfilled promise of “forty acres and a mule” promised to freed enslaved people after the Civil War.

For decades, HR 40 faced Republican opposition and died in committee. But momentum grew. In April 2021, the bill cleared committee for the first time in its thirty-year history. By 2025, the legislation had support from over 100 national and grassroots organizations and 85 members of Congress (Representative Ayanna Pressley’s office). The bill would create a thirteen-member commission to study slavery and discrimination, hold hearings, and recommend appropriate remedies to Congress (NPR).

The national conversation reveals deep divisions. Some opponents claim reparations are too expensive or unfairly discriminate against non-Black Americans. Some supporters insist reparations must include direct monetary payments to descendants of enslaved people. Others propose diverse remedies including education programs, healthcare access, and community investment. What unites reparations advocates is the conviction that slavery’s legacy continues harming Black Americans today.

Why This Moment Matters: Reparations Is Not About the Past

The four aldermen who refused to apologize for slavery revealed something critical about American resistance to reparations. They argued about semantics and shifted focus to contemporary issues. Yet their refusal to acknowledge historical harm directly connects to their apparent indifference to contemporary disinvestment in Black neighborhoods. When leaders cannot acknowledge that slavery, segregation, redlining, urban renewal, and police torture systematically extracted wealth and opportunity from Black Chicagoans, they cannot justify investing in repair.

Reparations is not about guilt or individual blame. It is about acknowledging that documented policies deliberately harmed Black people and continue harming them today. The wealth gap is not mysterious or cultural. It reflects decisions made by government officials and enforced through law. Black Chicagoans could not own property in most neighborhoods due to racial covenants. They could not access mortgages due to redlining. Their neighborhoods were demolished for urban renewal. Their family members were tortured by police. These were not accidents or unfortunate side effects. These were policies.

Chicago now moves toward addressing these documented harms through its Reparations Task Force. The city will study what reparations mean in Chicago’s specific context and develop recommendations for remedies. Meanwhile, efforts like Evanston’s program show that reparations are being implemented, despite conservative legal challenges. The national HR 40 movement continues building pressure for federal recognition of slavery’s ongoing impact.

The four aldermen who voted no represent a political faction unwilling to acknowledge historical reality. But their votes could not stop the 43 who voted yes. They could not prevent the Reparations Task Force from proceeding. They could not silence Black council members’ demand for accountability. Chicago is moving forward, even as some officials cling to historical denial. The question now becomes whether the city will deliver substantive remedies or merely symbolic apologies.

About the Author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.