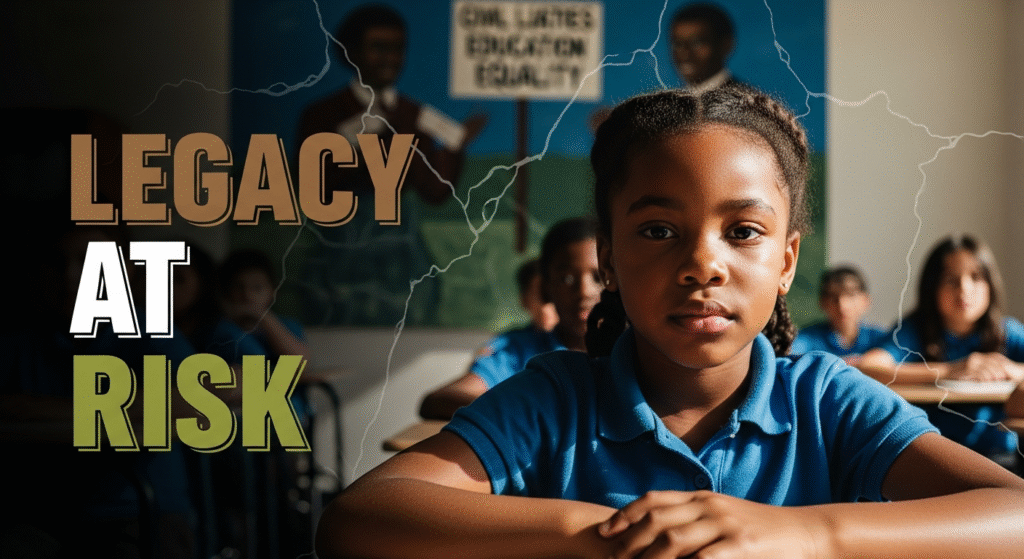

Civil Rights in Education: A Legacy at Risk

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Recent headlines from Washington D.C. have sent a chill through communities that have long fought for equal rights. The U.S. Education Department announced it will shift key civil rights work to other federal agencies. This move has sounded alarms for advocacy groups. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) warns this step weakens protections for students of color and students with disabilities in schools nationwide (ymaws.com). They say the department’s own mission now sits at risk. For many, this is not just a bureaucratic shuffle. It is a potential dismantling of protections that took generations of struggle to build. To understand why this news is so troubling, we must look at the history behind the headlines.

A Foundation Built on Struggle

The federal government’s role in protecting students began with the Civil Rights Movement. This was a pivotal struggle for social justice that aimed to secure full legal rights for African Americans (wikipedia.org). The movement’s goals extended beyond just desegregating lunch counters and buses. It fought for voting rights, economic equity, and an end to the systemic racism woven into American society (wikipedia.org). A central battlefield in this war for justice was the nation’s schools. Therefore, securing an equal education was seen as a fundamental step toward true freedom and opportunity.

A monumental victory came in 1954 with the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education. The court declared that state-sponsored segregation in public schools was unconstitutional (findlaw.com). This ruling was a legal earthquake. However, its implementation was met with massive resistance across the country. This fierce opposition made it clear that a court ruling alone was not enough. The federal government would need to actively enforce these rights to turn the promise of equality into a reality for Black children.

Landmark Laws for Equal Education

Congress responded to the need for enforcement with a series of powerful laws. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a comprehensive piece of legislation that laid the groundwork for federal power. Title VI of the act was especially critical. It prohibited discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in any program receiving federal money (justice.gov). This provision became a potent tool. Suddenly, federal funding was a lever that could be used to push reluctant school districts toward desegregation and fair practices.

The following year, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 became law (ed.gov). As a key part of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” this act sent large amounts of federal funding to primary and secondary schools. The War on Poverty was a set of programs aimed at reducing poverty, which disproportionately affected African American communities due to historical discrimination (gatech.edu). ESEA worked hand-in-hand with Title VI. The new funds gave the federal government even more leverage to promote equity by making aid dependent on non-discrimination (ed.gov).

The umbrella of protection continued to expand. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was the first federal civil rights law to explicitly ban discrimination against people with disabilities (congress.gov). Two years later, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) further guaranteed students with disabilities the right to a “Free Appropriate Public Education” (FAPE) tailored to their needs (ed.gov). These laws, along with Title IX’s ban on sex-based discrimination, created a strong legal framework for equality in education.

The OCR: A Dedicated Enforcer

To enforce this growing body of law, a dedicated agency was needed. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) was established for this exact purpose (ed.gov). Its mission is to ensure equal access to education and promote excellence through vigorous enforcement. In its early years, OCR played an enormous role in desegregating public schools. It investigated thousands of discrimination complaints and conducted compliance reviews to hold schools accountable.

One of the OCR’s most important tools is the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC). This is a survey conducted every two years that gathers extensive data from public schools across the country (ed.gov). The CRDC tracks key indicators like student discipline rates, access to advanced courses, and teacher experience, all broken down by race, disability status, and other factors. This data is indispensable. Consequently, it provides concrete proof of the disparities that still exist and allows OCR to target its enforcement efforts where they are needed most.

A Pattern of Weakened Protections

The recent announcement about shifting civil rights work away from these dedicated offices is seen by many as a retreat. The ACLU, a prominent organization that defends civil liberties, views this move as a direct threat that could undermine decades of progress (wikipedia.org). Advocates fear that diluting OCR’s authority will weaken protections for the most vulnerable students. A specialized agency like OCR has unique expertise and a clear mission. Spreading its duties across other agencies that may lack this focus could lead to less effective oversight.

These concerns are amplified by recent history. The Trump administration significantly altered OCR’s approach to civil rights. It downsized staff, closed regional offices, and narrowed the scope of investigations (federalism.org). This led to a dramatic increase in the number of cases being dismissed. The administration framed this shift as a move toward neutrality and local control. However, critics saw it as a weakening of protections for marginalized students (rsfjournal.org). The current announcement, therefore, feels like a familiar and dangerous step in the wrong direction for many advocates.

Discipline and the School-to-Prison Pipeline

One of the most urgent areas of concern is school discipline. Black students are consistently subjected to harsher punishments than their white peers, even for the same behavior (vcu.edu). This pattern contributes to what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.” This is a disturbing trend where harsh school discipline policies push students out of the classroom and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems (raceforward.org). This process can derail a child’s education and limit their future opportunities.

Statistics from OCR’s own data collections paint a stark picture. Black students are often suspended and expelled at rates three to four times higher than white students (edtrust.org). Without a strong OCR to investigate complaints and identify patterns of discriminatory discipline, advocates fear these disparities will grow. This could result in more Black children being pushed out of school and into a system that perpetuates cycles of inequality. Ultimately, less enforcement in this area puts the future of many Black students at risk.

Black students are suspended at a rate three times higher than their white peers. Data based on Civil Rights Data Collection reports (edtrust.org).

Academic Segregation and Lost Opportunity

Another critical area is access to advanced coursework. Even in schools that are technically integrated, a form of “academic segregation” often persists. This is when students are separated into different academic pathways, with Black students disproportionately placed in less rigorous tracks (uw.edu). This can happen through disparities in course offerings at schools that primarily serve Black students or biases in identifying students for gifted and talented programs. This practice limits opportunities and perpetuates achievement gaps (kappanonline.org).

Achievement gaps are the persistent differences in academic performance between different groups of students (impactpolicies.org). Data consistently shows that schools with more Black and Latino students offer fewer advanced math and science courses (edtrust.org). When Black students are denied access to Advanced Placement (AP) courses and experienced teachers, their chances of getting into college and succeeding in their careers are diminished. Advocates worry that without strong federal oversight, this academic segregation will become even more entrenched, stealing opportunities from another generation.

Black Student Representation

Black students are often underrepresented in advanced coursework compared to their share of the total student population (usccr.gov).

Protecting Students with Disabilities

The potential harm is also great for Black students with disabilities. These students stand at the intersection of racial and disability discrimination, making them uniquely vulnerable. Federal laws like IDEA and Section 504 are their shield, guaranteeing them the support they need to succeed in school. However, data shows persistent problems. Black students are often over-identified in certain disability categories, such as “emotional disturbance,” which can lead to more punitive measures and segregation from their peers (vcu.edu).

There are also serious concerns about whether these students receive adequate services and if their Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are properly implemented. The OCR is the agency that investigates when these rights are violated. Shifting this oversight away from a specialized office could lead to weaker enforcement. As a result, families may find it harder to get justice when their children are denied the free and appropriate public education they are legally promised.

Over-Identification in Special Education

Black students are 2.5 times more likely than other students to be identified as having an emotional disturbance (vcu.edu).

The Education Department’s decision to shift civil rights work represents a critical moment for educational equity. History shows that a strong federal commitment, enforced by a dedicated agency like the OCR, has been essential in the fight against discrimination. This oversight has been indispensable in moving the nation closer to the promise of equal educational opportunity for every child. The concerns raised by advocates are not abstract. Furthermore, they are rooted in the long struggle for justice and the real-world data that shows this fight is far from over. Upholding the promise of Brown v. Board of Education requires constant vigilance and an empowered federal commitment to civil rights, not a diffusion of that vital responsibility.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.