Listen to this article

Download AudioCongo Peace Deal: Minerals & Power

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Congo Conflict: A Deep Dive

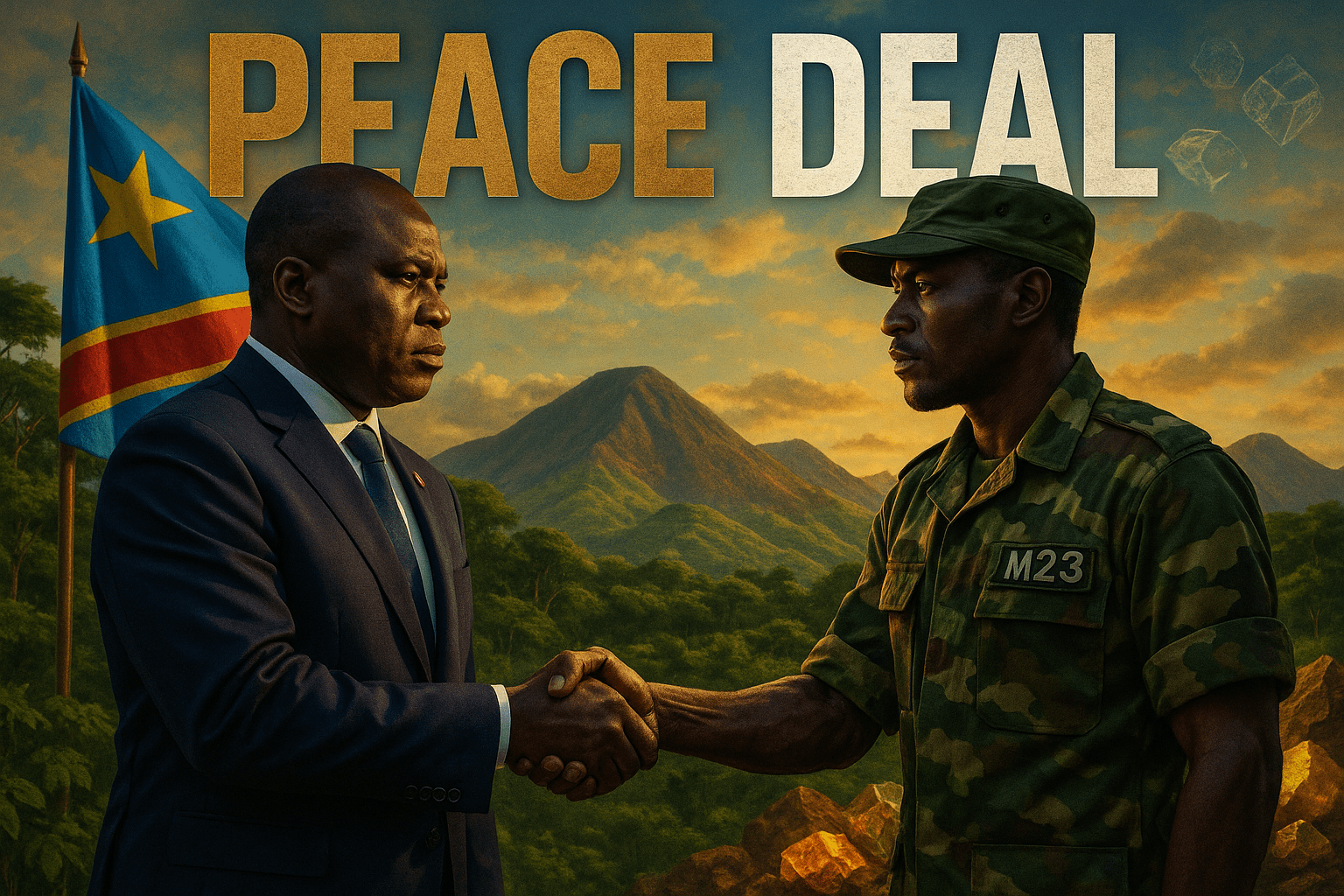

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and the M23 rebel group, which many believe is backed by Rwanda, have taken a significant step towards peace. On July 19, 2025, representatives from both sides signed a declaration of principles in Qatar. This declaration aims to pave the way for a full peace deal by next month (Reuters). This move follows months of mediation efforts by Qatar, which began in April (Reuters).

The signing ceremony took place in Doha, with Massad Boulos, the US special envoy for Africa, present as a witness (Bloomberg). Qatar’s government has been actively overseeing these peace talks (Bloomberg). The United States has also been pushing hard to finalize a lasting peace agreement in Congo. President Donald Trump has openly stated his hope that such a deal would encourage Western investment in the DRC, a nation rich in valuable minerals (Reuters).

M23 Rebels: Who Are They?

The M23 rebel group is a powerful armed force operating in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo, an area known for its vast mineral wealth (DW). This group has managed to seize more territory in Congo than it ever has before (Reuters). The conflict between the M23 and the DRC government has been going on for almost four years (Bloomberg). The M23 is considered the most prominent of about 100 armed groups active in this mineral-rich region (DW).

Rwanda has been accused of controlling the M23 rebels, even though Rwanda has always denied these claims (Reuters). Despite Rwanda’s denials, the M23 is often referred to as “Rwanda-backed” in reports about the conflict in eastern Congo (Bloomberg). A report by United Nations experts, obtained by Reuters in July 2025, stated that Rwanda did indeed exercise command and control over the M23 rebels during their advance (Reuters).

Declaration of Principles: What It Means

The “declaration of principles” is a document signed by the Congolese government and the M23 rebel group in Qatar. It sets out a timeline for reaching a full peace deal (Reuters). This declaration acts as a temporary ceasefire agreement and an “agreement to principles” that aligns with an earlier peace deal signed in Washington on June 27 (DW). It commits both sides to working towards a permanent truce and a comprehensive peace agreement (DW).

However, the specific terms and concessions of the final deal are not yet clear (DW). The declaration of principles lays out a new timeline, aiming for a peace deal next month (Reuters). Both sides have committed to signing a permanent truce and a comprehensive peace agreement by August 18 (DW). This timeline follows months of Qatari mediation, with talks commencing in April (Reuters). Despite this progress, some sources within both delegations have expressed frustration with the slow pace of negotiations and the lack of progress on confidence-building measures (Reuters).

US Involvement: Pressure and Investment

The United States has played a big part in pushing for peace in eastern Congo. It has put a lot of pressure on both sides to finalize peace deals and has hosted talks between Congo and Rwanda (Reuters). A major reason for US involvement, especially under President Donald Trump, is the hope of attracting Western investment into the DRC’s rich mineral resources (Reuters). Massad Boulos, the US special envoy for Africa, was a witness when the declaration of principles was signed in Doha (Bloomberg).

The US believes that a lasting peace deal in Congo could bring in billions of dollars in Western investment (Reuters). This is because the DRC is incredibly rich in minerals like tantalum, gold, cobalt, copper, and lithium (Reuters). These minerals are vital for modern technologies, including batteries for electric vehicles and electronic devices. The ongoing conflict in eastern Congo has prevented such investments and economic growth (DW).

Mineral Wealth and Its Impact

The Democratic Republic of Congo is incredibly rich in minerals. It has large deposits of tantalum, gold, cobalt, copper, and lithium (Reuters). These minerals are super important globally. Cobalt and lithium, for example, are key ingredients in batteries for electric cars and electronic gadgets. The hope for peace in eastern Congo, pushed by the US, is seen as a way to bring in billions of dollars from Western investors into this mineral-rich area (Reuters).

For almost 30 years, these minerals have fueled conflict and terrible violence, especially in eastern DRC. Minerals like tungsten, tantalum, and gold (often called 3TG) fund and drive the conflict. Government forces and about 130 armed groups fight for control over profitable mining sites. Several reports have pointed to Congo’s neighbors, Rwanda and Uganda, as supporting the illegal mining of 3TG in this region. The DRC government has struggled to control its vast territory and diverse population. Limited resources, logistical problems, and corruption have weakened its armed forces. This situation makes military help from the United States very appealing. However, our research shows there are risks involved.

Key Minerals in the DRC

Joint Oversight and Security

The peace deal includes a joint oversight committee with representatives from Rwanda, Congo-K, the US, Qatar, and an African Union representative, among others (Africa Confidential). This committee is designed to receive complaints and resolve disputes between the DRC and Rwanda. Furthermore, the agreement requires the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) high commands to set up a joint security mechanism (Africa Confidential).

While the declaration of principles aims to end fighting and achieve a comprehensive peace agreement, it does not explicitly state whether the M23 must withdraw from territories they currently control (DW). The focus is on reaching a permanent truce and a broader peace deal, but the specifics of territorial control and withdrawal are not detailed (DW). The declaration of principles does include a commitment to a temporary ceasefire, with the goal of achieving a permanent truce (DW). However, the information available does not detail the specific ways this ceasefire will be enforced or how civilians will be protected. While this agreement is a step towards peace, the practical details of keeping civilians safe amidst ongoing tensions are not fully explained.

The Cost of Resources-for-Security Deals

The peace deal between the DRC and Rwanda, brokered by the US, ties the two African nations to a concerning arrangement. It suggests that a country might give up its mineral resources to a superpower in exchange for vague promises of security. This deal, signed in June 2025, aims to end three decades of conflict between the DRC and Rwanda. A key part of the agreement requires both nations to develop a regional economic integration framework. This arrangement would increase cooperation between the two states, the US government, and American investors on “transparent, formalized end-to-end mineral chains.”

Despite its vast mineral wealth, the DRC remains one of the five poorest countries in the world. It has been seeking US investment in its mineral sector. The US, in turn, has promoted a potential multi-billion-dollar investment program to secure its mineral supply chains in this struggling territory. The peace promised by the June 2025 deal, therefore, depends on linking mineral supply to the US in exchange for Washington’s powerful, yet vaguely defined, military oversight. The peace agreement also sets up a joint oversight committee, with representatives from the African Union, Qatar, and the US, to handle complaints and disputes between the DRC and Rwanda. However, beyond this committee, the peace deal does not create specific security obligations for the US.

Impact of Conflict in Eastern Congo

The fighting has resulted in thousands of deaths this year.

Hundreds of thousands more have been displaced from their homes.

The conflict escalates the risk of a full-scale regional war.

Historical Tensions and Mineral Exploitation

The relationship between the DRC and Rwanda has been strained by war and tension since the First (1996-1997) and Second (1998-2003) Congo wars. A major cause of this conflict is the DRC’s immense mineral wealth. This wealth has fueled competition, exploitation, and armed violence. This latest peace deal introduces a “resources-for-security” arrangement. Such deals are not new in Africa. They first appeared in the early 2000s as “resources-for-infrastructure” transactions. In these deals, a foreign state would agree to build economic and social infrastructure, such as roads, ports, airports, and hospitals, in an African state. In return, it would gain a significant stake in a government-owned mining company or preferential access to the host country’s minerals.

We have studied mineral law and governance in Africa for over 20 years. The question now is whether a US-brokered resources-for-security agreement will truly help the DRC benefit from its resources. Based on our research on mining, development, and sustainability, we believe this is unlikely. This is because “resources-for-security” is the latest version of a resource-bartering approach that China and Russia pioneered in countries like Angola, the Central African Republic, and the DRC. Resource bartering in Africa has weakened the sovereignty and bargaining power of mineral-rich nations like the DRC and Angola. Furthermore, “resources-for-security” deals are less transparent and more complicated than previous resource-bartering agreements.

Risks to Sovereignty and Accountability

The DRC has huge deposits of critical minerals like cobalt, copper, lithium, manganese, and tantalum. These are the building blocks for 21st-century technologies, including artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, wind energy, and military security hardware. Rwanda has less mineral wealth than its neighbor but is the world’s third-largest producer of tantalum, which is used in electronics, aerospace, and medical devices. For almost 30 years, minerals have fueled conflict and severe violence, especially in eastern DRC. Tungsten, tantalum, and gold (known as 3TG) finance and drive conflict as government forces and an estimated 130 armed groups fight for control over profitable mining sites. Several reports have implicated the DRC’s neighbors, Rwanda and Uganda, in supporting the illegal extraction of 3TG in this region.

The DRC government has failed to secure its vast territory and diverse population. Limited resources, logistical challenges, and corruption have weakened its armed forces. This situation makes military support from the United States very attractive. However, our research shows there are traps. Resources-for-infrastructure and resources-for-security deals generally offer African nations short-term stability, financing, or global goodwill. However, the costs are often long-term because they erode sovereign control. This happens in several ways. Certain clauses in such contracts can prevent future regulatory reforms, limiting a country’s ability to make its own laws. Other clauses may lock in low prices for years, preventing resource-selling states from benefiting when commodity prices go up. Arbitration clauses often move disputes to international courts, bypassing local legal systems. Infrastructure loans are often secured using resource revenues as collateral. This effectively sets aside exports and undermines a country’s control over its own finances.

Key Milestones in the Congo Peace Process

Erosion of Sovereignty and Accountability

Examples of countries losing or almost losing their sovereignty because of these types of deals are common in Africa. For instance, Angola’s US$2 billion oil-backed loan from China Eximbank in 2004 was to be repaid in monthly oil deliveries, with revenues going into Chinese-controlled accounts. The way the loan was set up meant that Angolan authorities lost control over that income stream even before the oil was extracted. These deals also make it harder to hold people accountable. They often involve many government departments, such as defense, mining, and trade, which can avoid strong oversight. This fragmentation makes resource sectors vulnerable to “elite capture,” where powerful insiders can manipulate agreements for their own gain. In the DRC, this has led to a “violent kleptocracy,” where wealth from resources is systematically stolen instead of benefiting the people.

Finally, there is the risk of re-entrenching the trauma of extraction. Communities displaced for mining and environmental damage in many African countries show the long-lasting harm to livelihoods, health, and social cohesion. These are not new problems. However, when extraction is tied to security or infrastructure, such damage risks becoming permanent features, not just temporary costs. Critical minerals are “critical” because they are hard to mine or replace. Additionally, their supply chains are strategically vulnerable and politically exposed. Whoever controls these minerals controls the future. Africa must make sure it does not trade away that future. In a world being reshaped by global interests in critical minerals, African states must not underestimate the strategic value of their mineral resources. They have considerable power.

The Path Forward for Africa

However, power only works if it is used wisely. This means investing in stronger institutions and legal capabilities to negotiate better deals. It also means demanding local value creation and addition, requiring transparency and parliamentary oversight for agreements related to minerals, and refusing deals that ignore human rights, environmental standards, or national sovereignty. Africa has the resources. It must hold on to the power they bring. The conflict in eastern Congo has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, but the current information does not address how the peace deal will help with humanitarian needs or allow displaced people to return home. The focus is on ending the fighting and attracting investment, rather than specific humanitarian outcomes.

The African Union (AU) is involved in the peace process, with its Chair, Mahmoud Ali Youssouf, playing a role. The AU is part of the joint oversight committee, but the specific details of its role or that of other international groups in helping to carry out the peace agreement are not fully explained. The declaration of principles marks a big step in the ongoing efforts to achieve lasting peace, security, and stability in eastern DRC (DW). The peace deal could potentially bring in billions of dollars of Western investment to a region rich in minerals (Reuters).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.