Drought’s Deadly Grip: Fueling Violence and Extremism

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

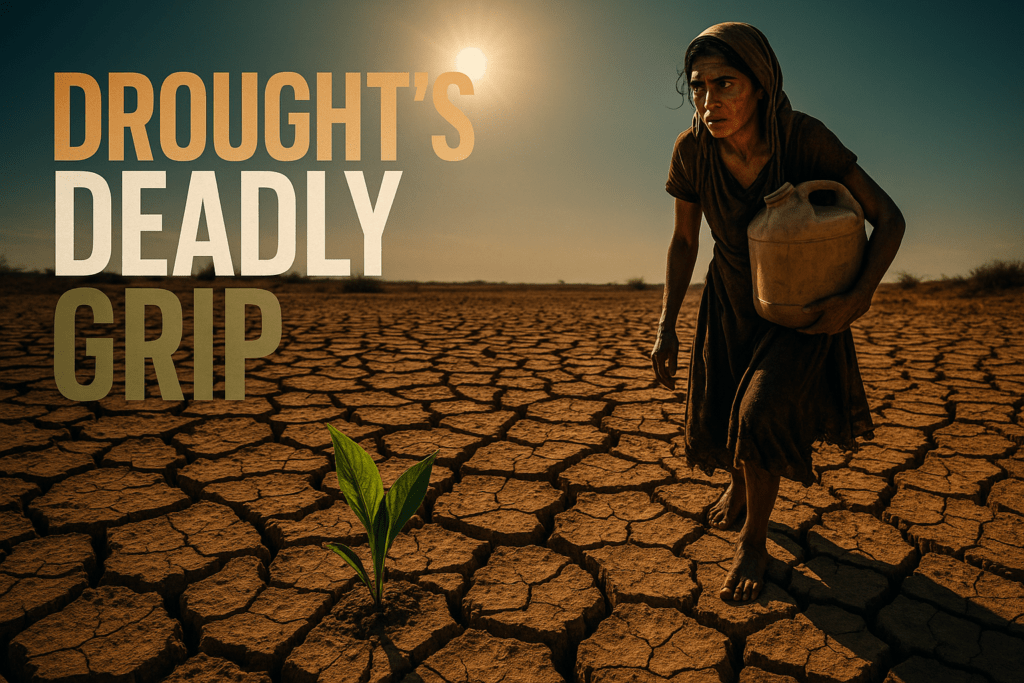

The Silent Scourge of Drought

Droughts are not sudden, explosive events like earthquakes or hurricanes. Instead, they are a creeping disaster, slowly tightening their grip on communities and leaving widespread devastation in their wake. A drought is a prolonged period of abnormally low rainfall, which leads to a severe shortage of water (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). This water scarcity impacts everything from drinking water supplies to food cultivation and the health of livestock. There are different ways drought shows up. For instance, meteorological drought means there is simply not enough rain. Agricultural drought occurs when the soil does not have enough moisture for crops to grow. Hydrological drought happens when water levels in rivers, lakes, and underground sources drop too low. These types often follow each other, with a lack of rain usually appearing first, then affecting farms and water bodies (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

The consequences of drought are profound, affecting people’s health, well-being, and livelihoods. Moreover, these dry spells are becoming more frequent and intense over time, with clear connections to the changing climate (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). When we speak of “extreme drought,” we are talking about a drought of exceptional severity or duration. This level of drought causes widespread and severe impacts on water resources, agriculture, and natural environments. While the exact measurements can differ by region, extreme drought generally means a significant and long-lasting drop in normal rainfall, leading to critical water shortages and serious social and economic problems. Satellite imagery and government records help us track these conditions, providing a clear picture of the scale of the crisis (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

A World Thirsty and Stressed

The numbers paint a stark picture of a world increasingly struggling with water scarcity. In 2022, more than 2.3 billion people faced water stresses (drought.unl.edu). The frequency and length of droughts have increased by 29 percent since the year 2000 (drought.unl.edu). The Horn of Africa, a region with deep historical and cultural ties to the African diaspora, has been particularly hard hit. Five straight seasons of below-normal rainfall led to a severe lack of surface water, widespread crop failures, dwindling pastures, and massive livestock losses (equalitynow.medium.com). This devastating combination of low rainfall and heatwaves was made 100 times more likely because of human-caused climate change, and these drought conditions are expected to continue (equalitynow.medium.com).

In Somalia, for example, an estimated 43,000 excess deaths occurred in 2022 alone due to drought-linked hunger. As of early this year, 4.4 million people, which is a quarter of Somalia’s population, face crisis-level food insecurity. An additional 784,000 people are expected to reach emergency levels of hunger. Across Eastern and Southern Africa, over 90 million people are facing acute hunger. These regions, home to many of our kin, are enduring some of their worst droughts ever recorded. The United Nations-backed study, “Drought Hotspots Around the World 2023-2025,” highlights that high temperatures and a lack of rain in 2023 and 2024 resulted in water supply shortages, low food supplies, and power rationing. Tens of millions in parts of Africa faced drought-induced food shortages, malnutrition, and displacement, according to the 2025 drought analysis by the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and the U.S. National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC).

Key Drought Impacts and Statistics

Violence Against Our Women and Girls

Droughts are a significant factor in increasing violence, especially against women and girls. This is a painful reality for many in our global family. Extreme drought in East Africa is leading to cases of violence against women and girls in the region (reliefweb.int). Violence against women and girls (VAWG) includes a range of harmful acts committed against individuals because of their gender. In times of drought, this can mean sexual violence and harassment, physical violence, intimate partner violence, and even the horrific practice of witch killings. It also includes early or forced marriage and emotional violence (thelancet.com).

These forms of violence are often made worse by economic instability, food insecurity, mental stress, broken infrastructure, increased exposure to men, and deeply rooted gender inequality (thelancet.com). Children, especially girls, are dropping out of school because drought forces families to move in search of food (reliefweb.int). This increases girls’ exposure to those who would harm them. In Somalia, data from IRC project sites shows that more younger girls are facing violence. This can be linked to increased displacement as families seek food, water, and pasture in unfamiliar and risky territories (reliefweb.int). The desperation to survive can push families to make impossible choices, leading to devastating consequences for their daughters.

Forms of Violence Against Women and Girls Exacerbated by Drought

- Sexual Violence and Harassment

- Physical Violence

- Intimate Partner Violence

- Witch Killings

- Early or Forced Marriage

- Emotional Violence

- Exploitation

- Forced Labor

Drought and Extremist Violence

The connection between drought and extremist violence is a complex but undeniable reality. Extremist violence, in this context, refers to violence carried out by groups or individuals who hold extreme political or religious beliefs. They often target civilians or specific communities to achieve their goals. While drought does not directly cause extremist violence, it can worsen existing vulnerabilities and grievances, creating an environment where recruitment and radicalization can thrive (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). This can show up as an increase in civil conflict, especially for groups who depend on farming or who are excluded from political power.

A study looking at civil conflict and growing-season drought found that for groups dependent on agriculture and those politically excluded in very poor countries, a local drought increases the chance of ongoing violence (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The study used new conflict data from Asia and Africa between 1989 and 2014, along with updated information on ethnic settlements and satellite data on agricultural land use, to analyze the relationship between drought and conflict (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Drought conditions can worsen existing social and economic tensions, contributing to conflict and potentially influencing the rise of extremist violence (undp.org). Daniel Tsegai, a drought expert and editor of the UNCCD study, explained that drought can become a “multiplier” for extremist violence in regions and communities already made vulnerable by years of drought. While climate change-driven drought does not directly cause extremist conflict or civil wars, it overlaps with and intensifies existing social and economic tensions, setting the stage for conflict and potentially boosting extremist violence.

The Perilous Journey of Migration

Drought-induced migration happens when people are forced to leave their homes because drought has severely impacted their way of life. This includes crop failures, livestock deaths, and a lack of water. This displacement often leads to a greater risk of violence and conflict (drought.unl.edu). The longer a drought lasts, the more it affects food, water, health, and sanitation, increasing the potential for migration and the conflicts that follow (drought.unl.edu). Migrants, especially women and girls, may face higher risks of violence, exploitation, and human rights violations in new and unsafe environments, particularly when they are searching for food, water, and pasture (reliefweb.int).

In Somalia, statistics show that more younger girls are facing violence compared to previous times. This can be linked to increased displacement as families seek food, water, and pasture, leading women and girls into unfamiliar and risky territories (reliefweb.int). The mass movement of people puts a strain on resources in host areas, often leading to conflict. Many displaced Somalis have even crossed into areas controlled by Islamic extremists. An earlier study found that drought in a Sub-Saharan district leads to 8.1 percent lower economic activity and 29.0 percent higher extremist violence. Districts with more months of drought in a given year and more consecutive years with drought experienced more severe violence. This highlights how social and economic tensions, such as disputes over dwindling water sources, land, and pasture, can lead to violence between communities. Economic hardship, like widespread joblessness and poverty, can also fuel anger and instability, potentially leading to social unrest and increased crime.

The Drought-Conflict-Migration Cycle

Why Women and Girls Bear the Brunt

It is a painful truth that women and girls are disproportionately affected by drought. This is due to existing gender inequalities and traditional societal roles. In many communities, women are primarily responsible for finding water, food, and household resources. These tasks become much harder and more dangerous during a drought (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). As resources become scarce, women and girls may have to travel longer distances, which increases their exposure to violence and exploitation. Economic hardship often leads to girls being pulled out of school for domestic duties or being forced into early marriage, further limiting their opportunities and increasing their vulnerability (reliefweb.int).

Drought can significantly increase the risk of child marriage and other human rights violations for girls (equalitynow.medium.com). When families face severe economic hardship because of drought-induced losses, they may turn to desperate coping mechanisms. This includes marrying off young daughters to reduce the number of mouths to feed or to get dowry payments (equalitynow.medium.com). This practice robs girls of their education, health, and freedom. Other human rights violations include increased exposure to sexual violence, exploitation, and forced labor as families migrate or struggle to survive. The UNCCD Deputy Executive Secretary, Andrea Meza, stated that around 85 percent of people affected by drought live in low- and middle-income countries, with women and girls being the hardest hit. Daniel Tsegai added, “Drought might not know boundaries, but it knows gender.” Traditional gender-based societal inequalities are what make women and girl children particularly vulnerable.

Global Reach, Local Impact

While much of the data highlights the severe impacts of drought in East Africa and the Horn of Africa, the ways drought leads to increased violence and social tensions are not limited to these regions. Research shows that extreme events, including droughts, are linked to increased gender-based violence worldwide (thelancet.com). The principles of economic instability, food insecurity, broken infrastructure, and worsened gender inequality as drivers of violence during and after droughts are likely true for other drought-prone regions globally. However, the specific ways these issues appear and how common they are may vary depending on local social, economic, and cultural conditions.

A mixed-methods systematic review included 41 studies exploring extreme events and gender-based violence. Most of these studies showed an increase in one or several forms of gender-based violence during or after extreme events (thelancet.com). This suggests that the underlying causes-economic instability, food insecurity, mental stress, disrupted infrastructure, increased exposure to men, tradition, and exacerbated gender inequality-are broadly applicable. For example, the 2006-2011 drought in Syria, considered the worst in 900 years, led to crop failures, livestock deaths, and mass rural displacement into cities. This created social and political stress, and economic disparities combined with authoritarian repression allowed extremist groups to exploit individuals facing unbearable hardships. This shows that the patterns seen in East Africa are part of a larger global phenomenon, affecting our people wherever they reside.

Understanding the Data and Pathways to Resilience

The data on violence and drought is collected and analyzed using various methods to ensure a thorough understanding. For instance, studies on the link between droughts and intimate partner violence often use information from women who are asked about their agency, mobility, household dynamics, and experiences with spousal violence (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Drought conditions themselves can be measured using different data sources, including satellite imagery for precipitation-based drought and government records for socioeconomic drought (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). These methods often involve GIS mapping and combining satellite data with weather station data to create detailed precipitation estimates (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

While the focus has been on the impacts, it is crucial to consider what measures can be taken to lessen the risks of violence and extremism linked to drought. Effective interventions would involve a multi-faceted approach. This includes strengthening early warning systems for drought and related risks, implementing climate-resilient agricultural practices to secure livelihoods, and providing humanitarian aid and social protection programs to vulnerable populations. Furthermore, programming that specifically addresses the needs and vulnerabilities of women and girls, such as safe spaces, mental health support, and economic empowerment initiatives, is vital. Addressing the root causes of gender inequality and promoting community-led ways to resolve conflicts can also help reduce tensions and prevent violence. As Daniel Tsegai noted, “building resilience to drought is a security imperative.”

A New Normal Demands Action

The global community must recognize that drought is no longer a distant threat. It is here, it is escalating, and it demands urgent global cooperation. When energy, food, and water all disappear at once, societies begin to unravel. This is the new normal that we must be ready for. The struggles faced by nations like Spain, Morocco, and Türkiye to secure water, food, and energy under ongoing drought conditions offer a preview of what water futures will look like under unchecked global warming. No country, regardless of its wealth or capacity, can afford to be complacent.

The economic impacts of an average drought today can be up to six times higher than they were in 2000, and costs are projected to rise by at least 35 percent by 2035. It is estimated that every dollar invested in drought prevention brings back seven dollars into the GDP that would otherwise be lost to droughts. This economic awareness is important for policymaking. The report released during the International Drought Resilience Alliance (IDRA) event aims to ensure that public policies and international cooperation frameworks urgently prioritize drought resilience and increase funding. For our communities, both on the continent and in the diaspora, understanding these connections and pushing for proactive solutions is not just a matter of policy, but a matter of survival and justice.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.