Haitian Deportations: A Deep Dive

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Understanding Irregular Status

The term “undocumented” or “irregular” status for Haitians in the Dominican Republic refers to individuals without the necessary legal papers to live or work there. This includes people who entered without permission, overstayed their visas, or were born in the Dominican Republic to undocumented parents and were not granted citizenship. The legal consequences are severe, often leading to arrest and deportation. For example, nearly 40,000 documented deportations occurred by November 2024, showing a large population considered to have irregular status (reliefweb.int). Many individuals deported are called “deportees and returnees,” meaning they are removed from the Dominican Republic because they lack legal residency (reliefweb.int).

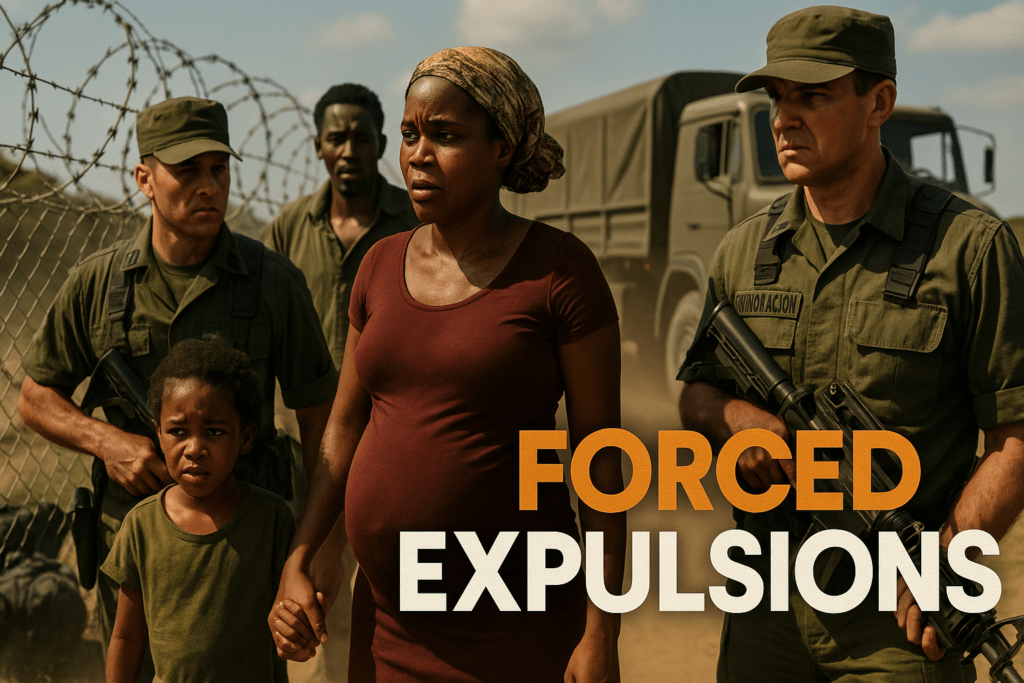

Reports also highlight the deportation of “pregnant women and unaccompanied and separated children (UASC)” (reliefweb.int). These vulnerable groups often have existing humanitarian needs, indicating their irregular status in the Dominican Republic and lack of legal protection. Furthermore, the term “apatridia” (statelessness) is mentioned in relation to human rights violations (amnesty.org). This implies that some individuals of Haitian descent born in the Dominican Republic are denied citizenship, making them undocumented in their birth country. This situation creates a constant state of vulnerability for many Haitians and those of Haitian descent.

Deportation Targets and Policy

The Dominican Republic has a clear policy of deporting undocumented Haitians, setting ambitious goals. President Luis Abinader has made these deportations a key part of his government’s policy, aiming for 10,000 deportations each week (csmonitor.com). In late 2024, the Dominican Republic announced it would begin massive deportations of Haitians living illegally in the country, with a target of expelling up to 10,000 per week (cnn.com). This policy, ordered by President Abinader, shows a high-level government decision to greatly increase deportations (npr.org).

The country’s Immigration Directorate reported that over 94,000 foreigners with irregular status were deported in the last three months of 2024 alone (cnn.com). This was part of an operation aiming to remove up to 10,000 undocumented Haitians per week. By November 18, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) had recorded nearly 40,000 deportations, with about 27,000 in October alone (reliefweb.int). This demonstrates a rapid increase in the pace of deportations following the announcement of the target. The government claims this policy is driven by a desire to control irregular migration and address national security concerns. However, the feasibility of consistently meeting such high targets remains uncertain, given logistical challenges and humanitarian issues.

Deportation Statistics (2023-2025)

Deportation Statistics (2023-2025)

This visualization shows the number of Haitians deported from the Dominican Republic in recent years.

The General Directorate of Migration

The General Directorate of Migration (DGM) is the main government agency in the Dominican Republic responsible for enforcing immigration laws. Its duties include managing borders, issuing visas and residency permits, and conducting operations to find, detain, and deport individuals with irregular immigration status. The DGM operates under the Ministry of Interior and Police and has wide authority to carry out immigration enforcement actions across the country. The DGM is implicitly the entity carrying out the “mass deportations” and “expulsion of thousands of Haitians” as described in various reports (theconversation.com). This indicates its central role in immigration enforcement.

Reports of “mounting abuses by Dominican officials” during deportation operations suggest that the DGM’s agents are the ones conducting raids and detentions (npr.org). Amnesty International’s report, which condemns human rights violations in the Dominican Republic, specifically mentions “violence in migratory operations” and “racial profiling” (amnesty.org). These actions are typically carried out by migration enforcement bodies like the DGM. The DGM’s aggressive tactics contribute to the fear and instability experienced by Haitian communities in the Dominican Republic.

Temporary Protected Status Explained

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is a United States immigration program. It grants temporary legal status to eligible foreign nationals from countries facing conditions that make it unsafe for their citizens to return. These conditions include armed conflict, environmental disasters, or other extraordinary and temporary situations. For Haitian migrants, TPS has been very important because it offered a temporary break from deportation and allowed them to live and work legally in the U.S. The U.S. decision to end TPS for Haitians would mean that those previously protected would lose their legal status, potentially facing deportation back to Haiti.

While the provided search results do not explicitly define TPS or discuss the U.S. decision to end it for Haitians, the context of mass deportations from the Dominican Republic highlights the uncertain legal status of Haitians in the region (theconversation.com). The lack of TPS or similar protections in neighboring countries like the Dominican Republic means Haitians lack a legal way to remain. The reports emphasize the “humanitarian impact of increased deportations” and the “brutality of mass deportations” (reliefweb.int). This underscores the lack of protected status for Haitians in the Dominican Republic, contrasting with the concept of TPS that offers temporary protection.

Haitian Laborers and Economic Impact

Haitian laborers are vital to several sectors of the Dominican economy, despite ongoing deportation efforts. Owners of farms, construction companies, and tourism businesses depend on Haitian laborers for demanding work (taipeitimes.com). For instance, on banana plantations in Mao, in the northwest of the Dominican Republic, most workers are from Haiti (taipeitimes.com). They perform arduous jobs that few Dominicans want to do. This reliance means that mass deportations can lead to significant labor shortages, increased production costs, and potential disruptions in these industries.

The economic impact extends beyond labor, as remittances from Haitian workers also contribute to the Dominican economy. The reports highlight the “mass deportations” and “expulsion of thousands of Haitians” (theconversation.com). By their sheer scale, these actions imply a significant removal of a labor force that would inevitably affect sectors that rely on them. While not explicitly detailing the economic impact, the large volume of deportations, such as 27,000 in October 2024 (reliefweb.int), suggests a substantial withdrawal of labor that would impact industries where Haitians are concentrated.

Estimated Haitian Population in DR

Estimated Haitian Population in DR

This visualization shows the estimated number of Haitians living in the Dominican Republic.

Human Rights and International Concerns

The deportation policy has raised serious concerns from international organizations and created fear within the Haitian community. International organizations have expressed worries about the impact of deportations on the Haitian community in the Dominican Republic (upi.com). Amnesty International, in a joint report to the UN Human Rights Committee, condemns human rights violations in the Dominican Republic (amnesty.org). This report specifically addresses “mass deportations of Haitian people,” “racial profiling,” and “violence in migratory operations.” The report also highlights the “deportation of pregnant women and minors,” “discrimination,” “apatridia” (statelessness), and “threats against human rights defenders” as specific human rights concerns.

The ACAPS report details that deportees “experience varied protection threats, including harassment, violence, extortion, and the denial of access to basic services” during the deportation process (reliefweb.int). This underscores the humanitarian impacts. Civil organizations have widely criticized the harsh new policy of mass deportations (npr.org). This indicates broad concerns from non-governmental bodies regarding human rights. Many Haitians now live in fear of detention and expulsion, which limits their access to basic services like healthcare and education (upi.com). Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent have been detained in various situations, including at hospitals before birth, returning from school, or simply for “looking Haitian” (csmonitor.com).

Fear and Access to Services

The fear of detention and deportation among Haitians in the Dominican Republic is widespread. This leads to limited access to essential services like healthcare and education. This fear shows itself in avoiding public spaces, being unwilling to seek medical attention even in emergencies, and children being pulled from schools. All of these actions are taken to avoid encounters with migration authorities. While specific data points on reduced access are not provided, the reported abuses during migratory operations and the widespread nature of deportations strongly suggest these chilling effects.

The Amnesty International report highlights “threats against human rights defenders” and the general climate of fear (amnesty.org). This would naturally extend to individuals seeking services. Deportees are reported to experience “the denial of access to basic services while living in the Dominican Republic and during the deportation process” (reliefweb.int). This directly illustrates limited access. Accounts of “unauthorized home raids” and “racial profiling” create an environment where Haitians would fear seeking public services (npr.org). This increases their risk of detection and deportation. The U.S. government’s announcement in late June to end temporary protected status for Haitians in September is expected to increase deportations of Haitians from the United States (csmonitor.com). This could potentially add to the pressure on the Dominican Republic.

The Deportation Process

Deportations in the Dominican Republic are often carried out through quick and aggressive operations. These frequently involve raids on homes and public spaces. Migrants are typically arrested and taken directly to the border. This often happens without formal legal proceedings, chances for appeal, or access to legal help. Protections for those being deported appear to be minimal. There are reports of human rights abuses, lack of due process, and the deportation of vulnerable individuals. Migrants recount “mounting abuses by Dominican officials” during deportations (npr.org). These include “unauthorized home raids” and “racial profiling,” suggesting a lack of formal legal proceedings.

The Amnesty International report explicitly mentions “violence in migratory operations” and “mass deportations” (amnesty.org). This implies a rapid and forceful process rather than a judicial one. The ACAPS report states that deportees “generally arrive with high pre-existing humanitarian needs” (reliefweb.int). Additionally, “many are deported without their belongings,” indicating a lack of orderly process or opportunity to gather possessions or prepare for return. The deportation of “pregnant women and unaccompanied and separated children (UASC)” without apparent due process further highlights the lack of protections (reliefweb.int).

Impact of Deportations

Impact of Deportations

This visualization highlights the various negative impacts of the Dominican Republic’s deportation policies on Haitian migrants and the broader community.

Haitians live in fear, limiting access to healthcare and education.

International organizations cite racial profiling, arbitrary detentions, and violence.

Labor shortages and increased costs in agriculture and construction sectors.

Dominicans of Haitian descent face denial of citizenship, leading to statelessness.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.