Houston Dumping: DOJ Ends Environmental Justice Deal

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

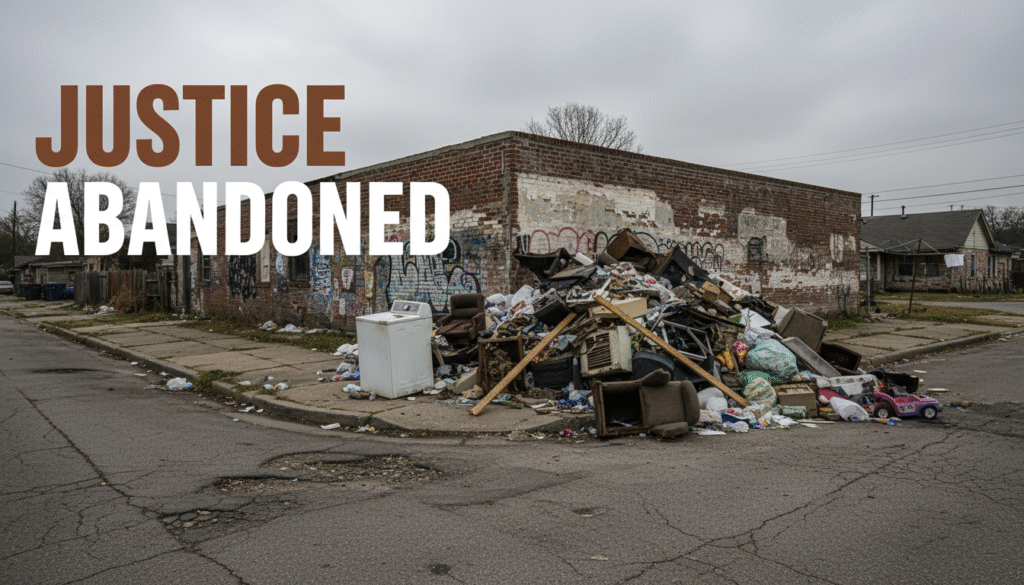

In Houston, Texas, a landmark agreement to protect communities of color has been cut short. The U.S. Justice Department has quietly ended its federal monitoring of illegal dumping in the city’s Black and Latino neighborhoods (washingtonpost.com). This program was part of a settlement aimed at correcting decades of environmental injustice. The withdrawal came in 2025, more than a year before the agreement was set to expire in June 2026 (washingtonpost.com). Now, residents report that the familiar piles of trash and pollution are returning. Local activists feel a deep sense of betrayal. They see this move as a significant step backward in the long fight for a clean and healthy environment for everyone.

The story of illegal dumping in Houston is not just about trash. It is a story about history, race, and power. For generations, Black and Latino residents have watched their neighborhoods become dumping grounds. They have suffered the health consequences while their calls for help went unanswered. The federal intervention in 2023 offered a brief period of hope and measurable progress (houstonlanding.org). However, its premature end raises serious questions about the nation’s commitment to civil rights and environmental protection for its most vulnerable citizens.

A Legacy of Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is not an accident. It is a system of policies and practices that place a disproportionate share of environmental hazards on communities of color (medium.com). This system includes targeting these areas for toxic waste disposal and failing to enforce environmental laws equally (medium.com). Houston provides a clear and painful example of this history. The city’s patterns of waste disposal were established long ago, creating a foundation of inequality that persists today.

This history was powerfully documented by Dr. Robert Bullard, who is widely known as the “father of environmental justice” (drrobertbullard.com). His groundbreaking research in the early 1980s exposed the stark reality in Houston. Dr. Bullard found that every single one of the city-owned garbage dumps was located in Black neighborhoods (reddit.com). Furthermore, 80% of city-owned incinerators and 75% of privately-owned landfills were also in these communities, even though African Americans made up only 25% of the city’s population at the time (reddit.com). This research proved that race, more than income, was the key factor in deciding where to put the city’s trash (drrobertbullard.com).

Houston Waste Facility Siting in Black Neighborhoods (1983)

Despite making up only 25% of the population, Black neighborhoods hosted a vast majority of the city’s waste sites.

City Dumps

City Incinerators

Private Landfills

Black Population

For decades, residents have lived with the consequences of this deliberate neglect. Illegal dump sites become breeding grounds for rats and mosquitoes, which carry diseases (washingtonpost.com). They are filled with everything from old furniture and construction debris to medical waste and animal remains (reddit.com). These piles of trash can block drainage systems, making flooding worse in already vulnerable areas. Moreover, exposure to airborne toxins from these sites leads to serious health problems, including respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular conditions (washingtonpost.com). Environmental injustice is not just unfair; it is a direct threat to the health and well-being of entire communities.

The Fight for Municipal Services

The daily reality of environmental racism often shows up in how a city responds to its residents. For years, communities of color in Houston used the city’s 311 service request line to report problems like illegal dumping (reddit.com). A 311 line is a non-emergency number for citizens to report urban issues such as potholes or missed trash collection. Data from this system revealed a clear pattern of discrimination. Between 2008 and 2011, predominantly Black and Hispanic council districts generated the majority of illegal dumping calls, reaching 66% of all calls by 2011 (reddit.com).

Despite making more calls, these communities received slower service. Community advocates alleged that the city consistently took longer to clean up dump sites in their neighborhoods compared to wealthier, whiter parts of town (reddit.com). For example, large piles of hazardous debris might sit for weeks or months in a Black neighborhood, while a similar report from an affluent area would be handled promptly. This unequal response sent a powerful message that the health and safety of some residents mattered less than others. It also created a cycle of neglect, where the constant presence of trash discouraged community pride and investment.

This fight for equal services was led by determined local activists and organizations. Lone Star Legal Aid filed the civil rights complaint that sparked the federal investigation (justice.gov). Community groups like the Trinity/Houston Gardens Super Neighborhood Council also played a vital role. In Houston, a Super Neighborhood Council is a volunteer group that gives a collective voice to local residents, allowing them to communicate their needs directly to the city government. Huey German-Wilson, president of her council, became a prominent voice for residents who felt ignored (washingtonpost.com). Their persistent advocacy brought national attention to the problem and forced the city and the federal government to act.

A Brief Hope: The Justice Department Intervenes

In July 2022, the U.S. Justice Department launched a civil rights investigation into the City of Houston (justice.gov). The investigation was based on the authority of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This federal law prohibits discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in any program that receives federal funding (jdsupra.com). Since municipal services receive federal money, they are required to serve all residents equitably. The investigation focused on whether Houston’s response to illegal dumping had a discriminatory effect on its Black and Latino residents (justice.gov).

This investigation resulted in a voluntary settlement agreement in June 2023 (justice.gov). Under the agreement, the city committed to implementing its “One Clean Houston” initiative. This plan included a budget of $17.8 million for the first two years to ramp up cleanup efforts (wastedive.com). It also involved tougher enforcement, with more video surveillance and inspectors to catch violators (reddit.com). A critical part of the agreement was a three-year period of federal monitoring to ensure the city followed through on its promises. Additionally, some city employees were required to undergo federal civil rights training to understand their legal obligations and prevent future discrimination (reddit.com).

During the period of federal oversight, the results were impressive. The city’s average response time for illegal dumping complaints dropped from 49 days to just 11 days (houstonlanding.org). Officials reported clearing over 2,900 dump sites and collecting nearly 20,000 tons of debris, a 24% increase from the previous year (houstonlanding.org). Criminal charges against violators increased fourfold (houstonlanding.org). For the first time in a long time, residents in affected neighborhoods saw real action. The agreement seemed to be working, proving that with proper oversight and resources, the city could provide the services its residents deserved.

Illegal Dumping Cleanup Response Time

Before Federal Monitoring

49

DAYS

During Federal Monitoring

11

DAYS

The Reversal: Backtracking on Justice

Despite this clear progress, the Justice Department withdrew from the agreement in 2025 (washingtonpost.com). The decision brought the federal monitoring to an abrupt end. This move is part of a broader shift in policy under the Trump administration, which has worked to dismantle environmental justice initiatives and roll back civil rights enforcement (washingtonpost.com). The administration issued an executive order halting many diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. It also initiated a change in how Title VI regulations are interpreted.

This change represents a significant new hurdle for civil rights cases. The administration is pushing for a standard that requires “proof of actual discrimination” (washingtonpost.com). This legal standard demands evidence that a policy was created with the specific *intent* to discriminate. This is much harder to prove than the previous standard, known as “disparate impact.” The disparate impact standard focused on the *effect* of a policy. If a policy resulted in a disproportionately negative outcome for a protected group, it could be challenged, even if no one admitted to having a discriminatory motive. By shifting the standard, the administration has made it far more difficult to address systemic inequality where racist intent is not openly stated.

For the communities in Houston, this legal shift is not an abstract concept. It is the reason why the federal government is no longer watching over their city. Without the pressure of federal oversight, local activists worry that city officials will revert to old habits of neglect. The progress they witnessed feels fragile and temporary. The withdrawal signals that their fight for justice has been deprioritized at the highest levels of government, leaving them to fend for themselves once again.

Shifting Legal Standards for Discrimination

Disparate Impact

This standard focuses on the EFFECT of a policy.

- Does a practice disproportionately harm a protected group?

- Proving discriminatory intent is not required.

- Used to address systemic and unintentional bias.

Actual Discrimination

This standard focuses on the INTENT behind a policy.

- Was the goal to treat a group differently?

- Requires proof of a discriminatory motive.

- Makes addressing systemic inequality much harder.

The Aftermath and Continued Struggle

With federal oversight gone, the situation on the ground in Houston is changing. Local activists report that the city has become less responsive to their complaints (washingtonpost.com). The trash piles and pollution that had begun to disappear are now a persistent problem again. Huey German-Wilson of the Trinity/Houston Gardens Super Neighborhood Council expressed the community’s despair. “We have nothing to fight with anymore,” she stated. “The city has no reason to respond to us, and we’re finding that they are truly ignoring us” (washingtonpost.com).

The broader societal impacts of illegal dumping are severe. Beyond the obvious health risks, it damages the economic fabric of a neighborhood. The presence of waste lowers property values, making it difficult for residents to build wealth (empowercdc.org). It also discourages new businesses from opening, limiting job opportunities and economic growth. This physical blight erodes community morale and can contribute to a sense of hopelessness. This is how environmental injustice perpetuates cycles of poverty and disadvantage.

Despite this setback, local activists are not giving up. They plan to continue their fight through different strategies. These include organizing more grassroots campaigns to document and report dumping. They will also increase direct advocacy with city council members to demand accountability. Using local media and social media to highlight ongoing problems can keep public pressure on city officials. As Houston prepares to produce over 5.4 million tons of waste annually by 2040, the challenge is immense (reddit.com). The struggle in Houston is a powerful reminder that the fight for environmental justice requires constant vigilance and unwavering determination.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.