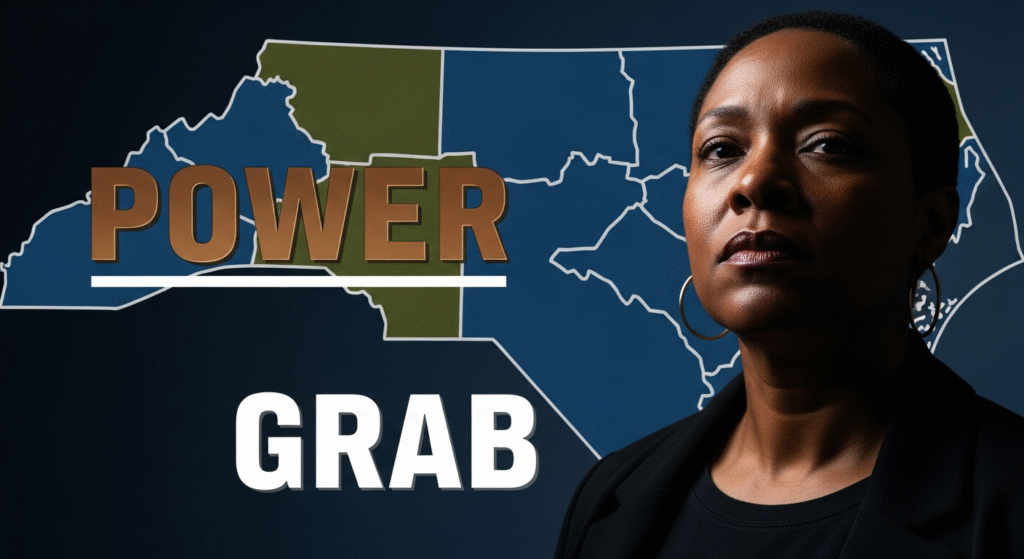

NC Court Lets GOP Maps Stand: A History

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

North Carolina is once again a key battleground over fair elections and voting rights. A recent federal court ruling upheld Republican-drawn U.S. House districts, even as civil rights groups argued the maps dilute the power of Black voters (ncsu.edu). Organizations like the state NAACP and Common Cause claim these maps intentionally break apart and pack Black communities to weaken their political influence (naacp.org). The decision allows these maps to be used for now, but the fight is far from over. To understand today’s headlines, it is necessary to look at the state’s long history of manipulating electoral maps. This story is about more than just lines on a map; it is about who holds power and whose voice is heard.

Defining the Lines of Power

Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries to give one political group an unfair advantage (africanelements.org). The goal is to control election outcomes before a single vote is even cast (africanelements.org). This often results in districts with strange, unnatural shapes that split communities (africanelements.org). When it comes to Black voters, this manipulation is called vote dilution. This practice minimizes the electoral power of African Americans, making it harder for them to elect candidates who represent their interests (africanelements.org). The two most common methods are “cracking” and “packing.” “Cracking” splits Black communities across several districts so they cannot form a majority anywhere (africanelements.org). Conversely, “packing” concentrates as many Black voters as possible into a single district. This guarantees a win in that one area but “wastes” votes and weakens their influence in all surrounding districts (africanelements.org).

The opposite of a gerrymandered map is a “fair” electoral map. Fair maps are guided by principles that promote equal representation. These districts are typically compact and connected (africanelements.org). They also respect existing boundaries like counties and cities, keeping communities of interest together (africanelements.org). These principles are meant to prevent the very manipulation that has defined North Carolina politics for generations. Therefore, the current legal battles are not just about political parties. They are a continuation of a historical struggle for fair representation and the protection of Black political power against systemic efforts to diminish it.

North Carolina Congressional Delegation Shift (2023 Maps)

A Legacy of Manipulation Since Reconstruction

North Carolina’s struggle with electoral maps is not new; it dates back to the Reconstruction era (ncsu.edu). After the Civil War, African American men gained the right to vote and hold office, leading to a period of unprecedented Black political participation (africanelements.org). Thousands of Black men were elected to local, state, and even federal positions (africanelements.org). This progress, however, was met with a violent white supremacist backlash (africanelements.org). One of the political tools used to suppress Black power was gerrymandering. From 1868 to 1898, Democrats in the state created the “Black Second” congressional district. They grouped as many Black Republican voters as possible into this single district (ncsu.edu). This tactic “packed” Black voters, ensuring their votes were concentrated in one place while diluting their ability to influence elections elsewhere in the state.

Another blatant example was the creation of Vance County in 1881 (ncsu.edu). Land from existing counties was redrawn to push Black voters into this newly formed county. While this might seem like it would concentrate Black power locally, it was a classic case of “packing.” By consolidating Black voters, their collective strength across the broader region was diminished (africanelements.org). Surrounding districts became whiter and more politically reliable for the Democratic party of that era (africanelements.org). Thus, this strategy effectively limited the total number of representatives Black voters could elect, creating a blueprint for vote dilution that has echoed for more than a century.

The Voting Rights Act and the Courts

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) was a landmark law that outlawed discriminatory voting practices (ncsu.edu). A key part of the VRA was Section 5, which established a “preclearance” requirement. This meant that certain states and counties with a history of discrimination, including 40 counties in North Carolina, had to get federal approval before changing any voting laws (ncsu.edu). Preclearance was a powerful preventative tool, stopping discriminatory rules before they could harm voters (africanelements.org). For example, under preclearance, Black voter registration in the covered North Carolina counties jumped from 38% in 1966 to 54% in 1976 (ncsu.edu). Section 2 of the VRA also provides a permanent, nationwide ban on voting practices that result in discrimination, even without proof of racist intent (africanelements.org).

North Carolina’s maps were repeatedly challenged in court under the VRA. In *Thornburg v. Gingles* (1986), the Supreme Court found that the state’s legislative districts discriminated against Black voters, particularly through at-large elections that diluted their power (ncsu.edu). At-large elections allow a white majority to control every seat in a jurisdiction, even if Black voters are a significant minority (africanelements.org). Later, in *Shaw v. Reno* (1993), the Court challenged a “majority-minority district” designed to increase Black representation (ncsu.edu). The oddly shaped district was ruled an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, creating stricter rules for drawing districts to empower minority voters (africanelements.org). These cases show the complex legal tightrope of race and redistricting. Ultimately, the VRA provided critical tools to fight for fair representation, but its interpretation has been continuously contested in court.

Growth in Black Voter Registration in North Carolina

A Shift in Legal Strategy

The legal landscape changed dramatically in the last decade. After Republicans gained control of the North Carolina General Assembly in 2010, they began an aggressive era of redistricting (ncsu.edu). Their efforts were aided by two key Supreme Court decisions. In *Shelby County v. Holder* (2013), the Court struck down the formula used to determine which states needed preclearance (ncsu.edu). The Court argued the formula was based on outdated data, but the decision effectively gutted the VRA’s power to prevent discrimination before it happens (africanelements.org). Without federal oversight, North Carolina lawmakers quickly passed restrictive voting laws, including a strict voter ID law (ncsu.edu).

Then, in *Rucho v. Common Cause* (2019), the Supreme Court declared that partisan gerrymandering was a “political question” that federal courts could not rule on (ncsu.edu). The Court reasoned there was no clear standard for judges to decide how much partisanship is too much (africanelements.org). This ruling separated partisan gerrymandering from racial gerrymandering, which remains illegal under federal law (africanelements.org). Republican lawmakers in North Carolina now openly state their maps are drawn for partisan advantage. They argue this is legal, pointing to the *Rucho* decision and a 2023 North Carolina Supreme Court ruling that affirmed partisan gerrymandering is permissible under the state constitution (ncsu.edu). Consequently, the legal fight has shifted. Civil rights groups must now prove that race, not just partisanship, was the primary motive behind the maps, a much harder case to win.

The Fight Over the 2023 and 2025 Maps

The current lawsuits filed by the NAACP and Common Cause target congressional and legislative maps drawn in October 2023 (ncsu.edu). Plaintiffs argue these maps illegally dilute Black voting strength through careful “packing” and “cracking.” One of the most contested areas is North Carolina’s First Congressional District (CD-1), historically an “opportunity district” where Black voters had a strong ability to elect their preferred candidates (africanelements.org). An opportunity district is designed to give a minority group a realistic chance to elect representatives who reflect their interests (africanelements.org). CD-1 has long served this role for Black voters in the state (africanelements.org).

A newly proposed 2025 map is described by advocates as an “escalation” and a “surgical strike on Black political power” (ncsu.edu). Lawsuits claim this map “perfectly cracks” the Black population between CD-1 and a neighboring district, reducing the Black voting-age population in CD-1 by about 8% (ncsu.edu). This seemingly small shift makes it “extremely unlikely” for Black-preferred candidates to win in either district (ncsu.edu). A “Black-preferred candidate” is identified through statistical analysis of voting patterns in predominantly Black areas (africanelements.org). When a candidate receives overwhelming support from these precincts, they are considered the choice of that community (africanelements.org). The recent federal court decision to let the 2023 maps stand means that this alleged dilution will continue, at least until an appeal can be heard by the Supreme Court (ncsu.edu). Therefore, this fight is about preserving the few remaining districts where Black voices can directly translate into political representation.

Dilution of Black Voting Power in NC CD-1

The proposed 2025 map is alleged to reduce the Black Voting Age Population (BVAP) in Congressional District 1 by approximately 8% (ncsu.edu).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.