Somali Pirates Return: How Collapsed Governance and Illegal Fishing Are Reigniting Maritime Insecurity in the Indian Ocean

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at Patreon and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, gain early access to ad-free video content.

Piracy Makes Its Dangerous Return: Coastal Livelihoods Under Siege

After more than eighteen months without a successful vessel hijacking, Somali pirates have returned to international waters with a vengeance. On Thursday, November 6, 2025, pirates armed with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades stormed the Malta-flagged tanker Hellas Aphrodite approximately 560 nautical miles southeast of Eyl, Somalia (Al Jazeera). The attack marked the first commercial vessel seizure in one and a half years, striking fear into maritime traders and coastal communities alike. As the week progressed, another liquefied natural gas tanker barely escaped a pirate speedboat assault, signaling that these attacks were no isolated incident (Reuters).

The resurgence has prompted warnings from industry leaders and environmental advocates. Osman Yusuf, a prominent conservationist and chairman of Prestige Fishing Company, issued an urgent alert about the threats facing Somalia’s fishing communities (African News). Yusuf criticized the effectiveness of the security measures currently in place, questioning the impact of last year’s maritime defense agreement between Somalia and Turkey. The irony cuts deep: while the international community gathers to combat pirates, the underlying conditions that spawn piracy continue to fester. For Somali fishermen and coastal residents, the situation represents a catastrophe unfolding in slow motion, threatening the livelihoods of thousands who depend on the sea.

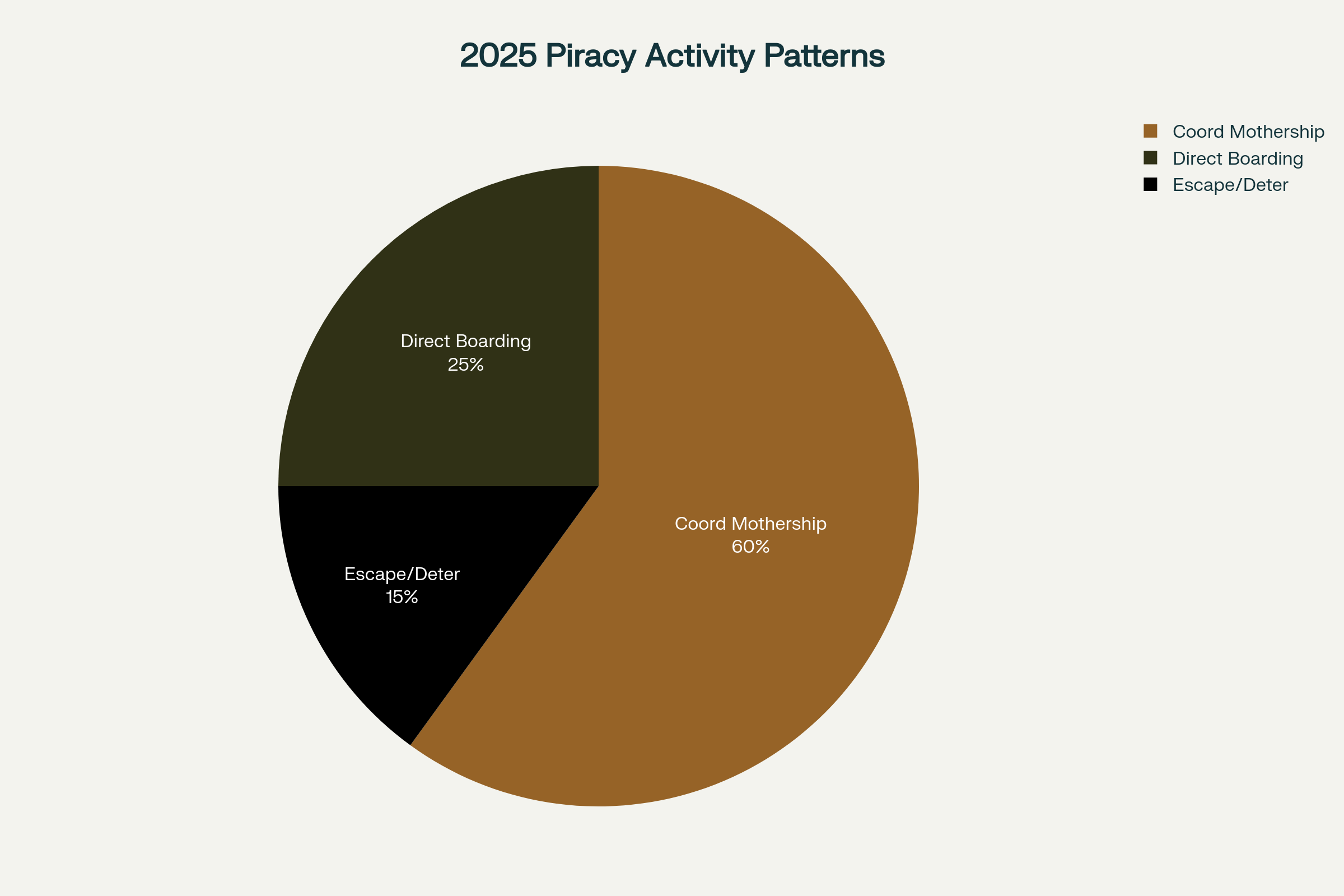

These recent incidents carry profound implications for the region. The attacks employ a tactical sophistication unseen in recent years. Pirates are now hijacking fishing vessels to use as motherships, extending their operational range far into the Indian Ocean (Skuld). According to maritime security firm Ambrey, Somali pirates captured an Iranian fishing boat called the Issamohamadi and have repurposed it as a floating base for coordinated attacks (NBC News). This evolution demonstrates that piracy has moved beyond desperate individuals in small boats. Modern Somali pirates are organized, well-armed, and strategically sophisticated.

Coastal Communities Watch Maritime Security Crumble

The 24 crew members aboard the Hellas Aphrodite huddled in the ship’s citadel as attackers fired automatic weapons at the vessel (BBC). The ship had sailed without armed security personnel on board—a calculated risk that backfired dramatically. EU Naval forces responded, ultimately freeing the crew and forcing pirates to abandon the vessel. However, the incident exposed vulnerabilities across the region. Therefore, maritime professionals have grown increasingly anxious about what may come next.

Timothy Walker, a senior maritime analyst at the Institute of Security Studies, offered sobering analysis to international press organizations. According to Walker, “We are observing a rise in reports of pirate groups seizing vessels and recruiting new members, as well as arming themselves. These are significant indicators that attacks are more likely, especially given the reduced deterrence compared to the past, allowing some groups to take risks and succeed in their endeavors” (ABC News).

For local fishermen like Osman Abdi, the psychological toll runs deep. Reports of pirate attacks fuel stigma and fear throughout coastal regions, making ordinary maritime commerce feel impossibly dangerous (African News). What happens when entire communities become afraid to work? When young people abandon fishing because the ocean has transformed into a war zone? Subsequently, these human costs extend far beyond shipping lane security or ransoms negotiations—they threaten the cultural fabric and economic survival of East African communities who have fished these waters for centuries.

History’s Shadow: Colonial Exploitation Birthed Modern Piracy

Understanding today’s piracy crisis requires looking backward at how foreign powers carved up Somali resources. Starting in 1875, European imperial powers—Britain, France, and Italy—scrambled for control of the Somali peninsula (United Nations Member States). Britain sought to secure coaling stations and ports for ships sailing to Indian colonies. The Red Sea was a crucial shipping lane to British colonial possessions, and Berbera on the Somali coast became a strategic prize. What followed was systematic exploitation of Somalia’s maritime riches and territorial sovereignty.

This colonial pattern established a precedent that would echo across the decades. Foreign powers treated Somali waters as an open resource to exploit rather than a territory whose people deserved sovereignty over their own livelihood. After Somalia gained independence in 1960, the young nation inherited weak maritime governance structures and a legacy of external intervention (Sea Around Us). The newly independent government struggled to establish effective control over territorial waters stretching across one of continental Africa’s longest coastlines at 3,333 kilometers (Hakai Magazine).

During the 1980s and early 1990s, foreign fishing vessels increasingly dominated Somali waters. Italian, Indian, Pakistani, and Iranian trawlers harvested fish using unsustainable methods including bottom trawling and nets with dangerously small mesh sizes (Wikipedia – Piracy off Somalia). Foreign fishing increased more than twenty-fold since 1981, with the most explosive growth occurring during the 1990s precisely when Somalia’s central government collapsed (Wikipedia – Piracy off Somalia).

State Collapse and Environmental Catastrophe: The Perfect Storm

In 1991, Somalia’s government imploded. The authoritarian regime of Siad Barre fell to armed opposition forces, triggering a devastating civil war that would last for decades. With the collapse, the Somali Navy disbanded entirely in 1990-1991, leaving territorial waters defenseless (Wikipedia – Piracy off Somalia). Suddenly, foreign fishing fleets operated without any oversight whatsoever. Meanwhile, foreign ships began dumping industrial waste and other contaminants into Somali waters.

Environmental catastrophe accompanied state collapse. Following two seasonal rain failures in 2008, millions of Somalis lost their livelihoods and faced famine and poverty (Climate-Diplomacy). Fish populations that had sustained coastal communities for generations were being decimated by overfishing. The situation became desperate. According to research from Secure Fisheries, illegal fishing destroyed sensitive marine habitats and reduced fish stocks beyond recovery (Hakai Magazine).

In response, Somali fishermen did what desperate people do—they organized. Small fishing communities banded together to create armed groups intended to defend what remained of their fish stocks (Wikipedia – Piracy off Somalia). They used motorized skiffs and small boats to intercept foreign trawlers and hold crews for ransom. At first, these actions resembled Robin Hood-style resistance—protecting community resources from foreign exploitation. However, the practice evolved into an increasingly lucrative criminal enterprise where enormous ransom demands replaced conservation concerns.

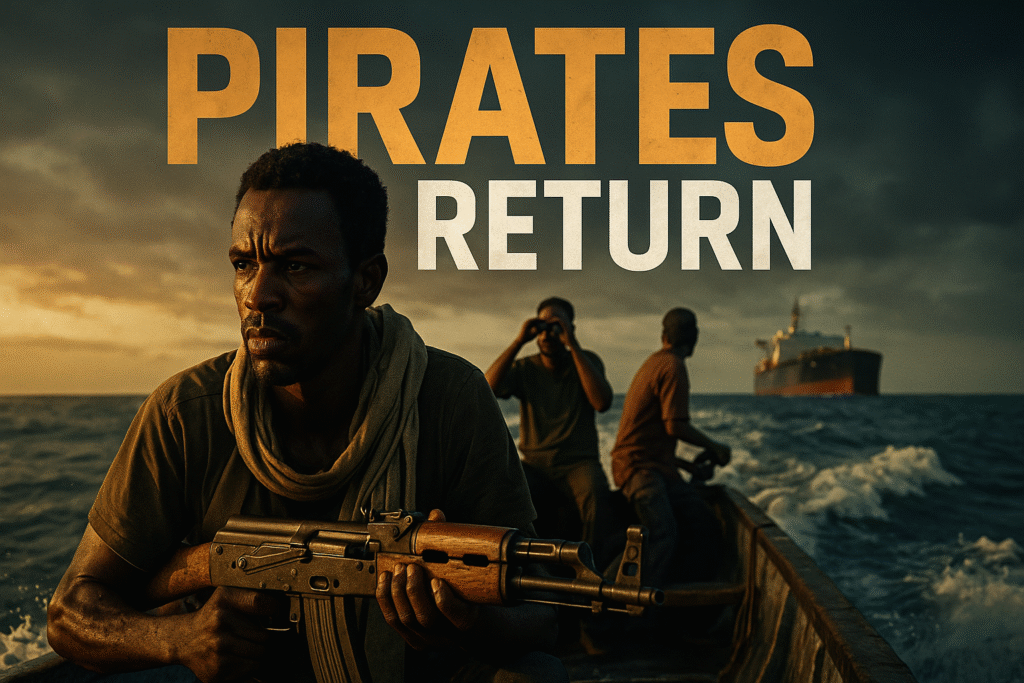

The 2011 Peak: When Piracy Reached Global Crisis Levels

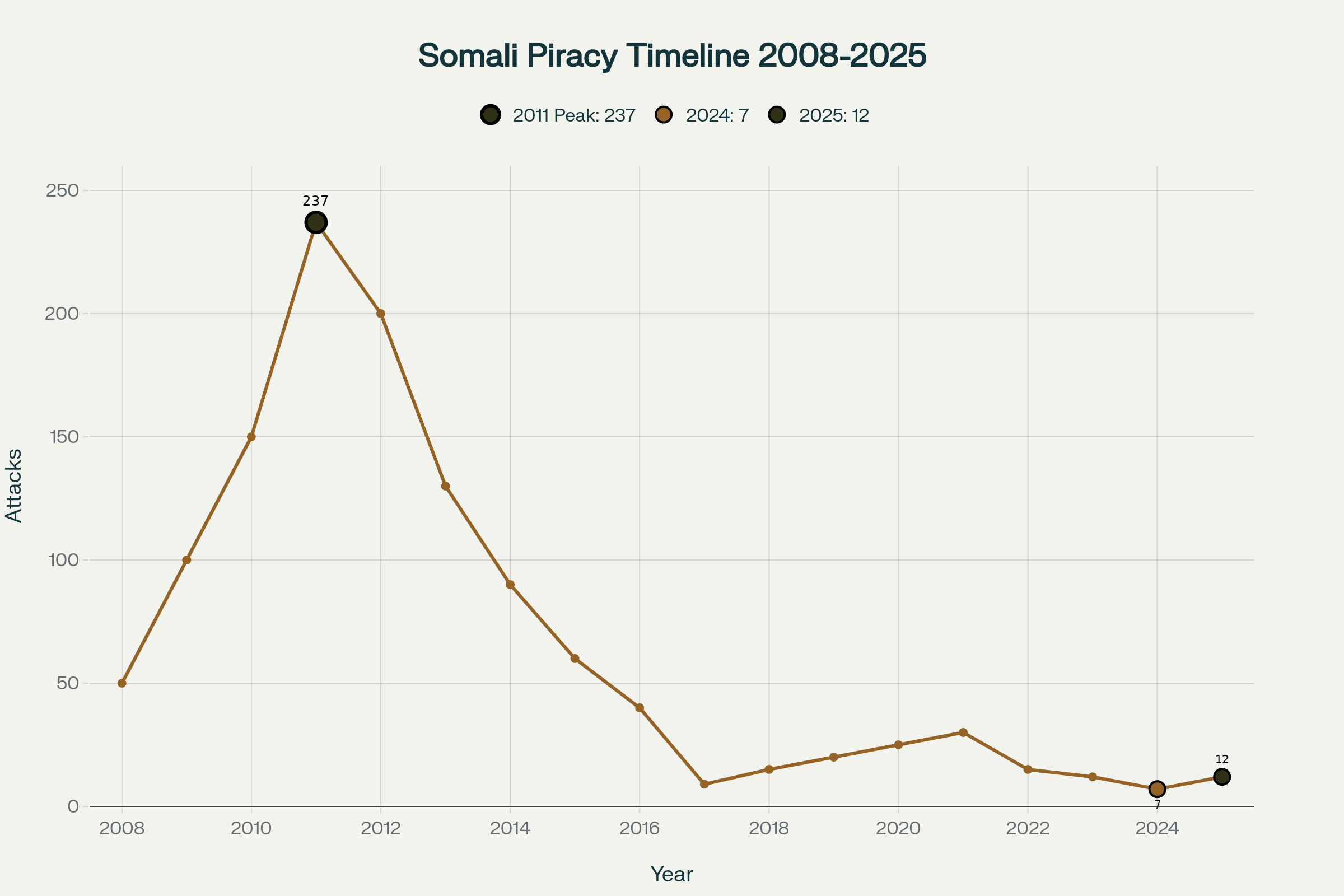

The situation reached catastrophic proportions by 2011. That year, 237 piracy attacks were reported off the Somali coast (NBC News). The scale of disruption shocked the international shipping industry. Between ransoms and disrupted commerce, Somali piracy inflicted approximately \$7 billion in losses on the global economy, with an estimated \$160 million paid directly in ransoms (NBC News). For perspective, this economic damage exceeded the gross domestic product of entire nations. Furthermore, the crisis forced naval powers to establish permanent anti-piracy operations, diverting military resources from other global challenges.

This peak seemed unsustainable. International naval operations from multiple countries surged into the Indian Ocean to combat piracy. The European Union launched Operation Atalanta in December 2008 specifically to protect shipping and disrupt piracy (Operation Atalanta Wikipedia). Meanwhile, rising military presence, improved shipping security practices, and a gradually strengthening Somali government combined to reduce piracy attacks dramatically. By 2017, incidents had fallen to just nine (The Conversation). For more than six years, piracy seemed to be a problem being solved.

The Houthi Connection and Geopolitical Realignment: New Drivers of Piracy

Beginning in late 2024, warning signs emerged that the piracy landscape was shifting. According to a United Nations report from February 2025, representatives from Yemen’s Houthi movement (formally Ansar Allah) and Somalia’s al-Shabaab terrorist group had met at least twice to discuss cooperation (Carnegie Endowment). Under the reported arrangement, Ansar Allah would provide al-Shabaab with advanced weapons and technical expertise. In exchange, al-Shabaab would intensify piracy attacks and coordinate ransoms collection in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters (Carnegie Endowment).

This partnership reflected the broader geopolitical consequences of the Israel-Hamas conflict in Gaza. Since October 2023, Houthi rebels have launched systematic attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean under the guise of supporting Palestinians (NBC News). These attacks have disrupted global shipping lanes, deterred merchants from certain routes, and created conditions ripe for piracy resurgence. Additionally, the reported arrangement includes al-Shabaab receiving a twenty percent share of ransoms collected by pirates (Carnegie Endowment)—meaning terrorist financing flows directly from maritime crime.

Consequently, piracy has transformed from a maritime crime into a geopolitical weapon wielded by armed groups fighting proxy wars across East Africa and the Middle East. The consequences cascade outward in unpredictable ways. As naval forces have been redistributed to address Houthi threats elsewhere, Somali coastal security weakened. Puntland authorities, who previously received direct funding from the United Arab Emirates to patrol territorial waters, have redirected most resources toward fighting the Islamic State in Somalia, which has rapidly gained territory in the Galgala region (Lloyd’s List).

Climate Crisis and Environmental Justice: The Forgotten Root Cause

Behind the headlines about pirates and international naval operations lies an environmental catastrophe that Western media largely ignores. Climate change is fundamentally reshaping East African fisheries. As ocean temperatures warm, fish populations shift beyond the reach of local fishermen using traditional small-boat methods (The Conversation). Extended droughts and severe weather conditions have intensified food scarcity and poverty on land. Young people who might have become farmers discovered that pastoral livelihoods were disappearing. Subsequently, the sea became one of the only remaining options—either as fishermen or, when desperation mounted, as pirates.

Research examining Somalia’s fisheries found that illegal foreign fishing costs Somalia approximately \$300 million annually in lost economic value (Policy Center for the African Union). To contextualize this loss: \$300 million annually represents genuine wealth extraction from one of Africa’s poorest nations. One researcher described this as an imbalanced “resource swap,” with maritime resources enriching foreign fishing corporations far more than the ransoms do for pirates (Policy Center for the African Union).

A paradox creates additional hardship: when international naval forces arrived to combat piracy, their presence ironically enabled increased illegal foreign fishing. The presence of military vessels offered protection to fishing trawlers, allowing them to operate more freely than when pirate deterrence kept them away (Hakai Magazine). This contradiction encapsulates the deeper structural failure: neither the international naval presence nor the Somali government has effectively protected marine resources for local use.

The Somalia-Turkey Agreement: Promises Without Guarantees

Last year, Somalia’s government reached a defense and economic agreement with Turkey designed to strengthen maritime security across Somali territorial waters (EurasiaReview). Under the arrangement, which will remain in force for a decade, Turkey committed to training Somali naval forces, conducting joint operations, sharing maritime intelligence, and helping Somalia acquire naval equipment (ENACT Africa). The partnership specifically aimed to curtail illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing by foreign vessels.

However, the deal has sparked controversy and raised questions about whether foreign powers can genuinely protect Somali interests. Osman Yusuf’s public questioning of the agreement’s effectiveness reveals deep skepticism within Somalia’s own fishing industry (African News). Moreover, subsequent reporting revealed that Turkish fishermen will themselves be permitted to operate in Somali waters under the arrangement (Turkish Minute). When Turkey signed a maritime defense agreement to protect Somali waters, it simultaneously negotiated the right to fish those waters. The deal transformed into something fundamentally different from marine resource protection—it became an economic access agreement benefiting foreign interests.

Somali authorities framed this as sustainable cooperation that would bring technical expertise and beneficial knowledge transfer. Yet history demonstrates that foreign fishing access agreements rarely benefit local communities. Therefore, Osman Yusuf’s warnings carry the weight of historical experience. He knows that foreign agreements routinely fail to protect Somali fishing communities and that maritime security arrangements typically prioritize international shipping interests over local livelihoods.

Structural Vulnerability: Why Somali Piracy Keeps Resurfacing

The resurgence of Somali piracy reveals systemic vulnerabilities that persist despite decades of international intervention. First, the underlying causes of piracy—poverty, environmental degradation, limited legitimate economic opportunities, and weak maritime governance—remain essentially unchanged (The Conversation). No international naval operation can bomb poverty into submission or shoot hunger away. As long as young Somali men lack viable economic alternatives, some will turn to maritime crime as survival strategy.

Second, the problem of illegal foreign fishing directly fuels piracy recruitment and support. When foreign vessels extract hundreds of millions of dollars worth of fish annually while local communities starve, the moral legitimacy of opposing piracy evaporates. Young men watch foreign trawlers destroy the marine ecosystem their families depend upon while their own government lacks the capacity to stop it. Subsequently, piracy becomes not merely a crime but a form of resistance, however misguided and destructive.

Third, geopolitical chaos in the broader region destabilizes everything in Somalia. The Israel-Hamas conflict prompted Houthi attacks on Red Sea shipping. Those attacks required naval responses that diverted military attention from Somali piracy prevention. Meanwhile, al-Shabaab’s continued insurgency consumes resources that could otherwise fund maritime security. Regional conflicts ripple outward, compromising the ability of any single nation to secure its waters.

What This Means for African Diaspora Communities and Global Supply Chains

The resurgence of Somali piracy carries particular significance for Black diaspora communities and African nations dependent on maritime trade. Higher insurance premiums for shipping through pirate-affected waters translate into increased costs for importing goods into Africa. These costs cascade down to African consumers. Additionally, seafaring remains one of the few international employment opportunities available to young Africans, and piracy threats make legitimate maritime careers more dangerous and economically uncertain.

Furthermore, the ability of armed groups like al-Shabaab to finance operations through piracy partnerships strengthens terrorist organizations that terrorize African populations. The reported twenty percent ransom share flowing to al-Shabaab finances operations that commit suicide bombings, kidnappings, and extortion throughout Somalia and Kenya. Piracy is not simply an international maritime security issue—it is a financing mechanism for terrorism targeting African communities.

For global supply chains, Somali piracy resurgence threatens routes carrying oil, liquefied natural gas, grain, and manufactured goods. A single major incident like the Hellas Aphrodite hijacking can disrupt commerce worth billions and prompt rerouting that adds weeks to shipping times. During the 2008-2012 piracy peak, some vessels avoided the Suez Canal route entirely, adding thousands of kilometers to journeys. Such disruptions raise costs that ultimately affect prices across the African continent.

Why This Matters Today: Addressing Root Causes Before Crisis Deepens

The current piracy resurgence offers a moment of clarity about what actually drives maritime crime in Africa. It is not primarily a lack of international naval firepower or military operations. Rather, it reflects the intersection of colonial legacy, environmental catastrophe, geopolitical chaos, and the persistent failure to establish legitimate governance and economic opportunity in coastal Somalia.

Additionally, addressing the piracy crisis requires confronting uncomfortable truths about illegal foreign fishing that international powers prefer to ignore. Foreign trawlers operating in Somali waters benefit powerful economic interests in wealthy nations. Serious maritime security would require these nations to police their own fishing industries—an unlikely outcome given the economic stakes involved.

Moreover, climate change will intensify these pressures across African coastlines. As ocean temperatures rise and fish stocks move, coastal communities in West Africa, East Africa, and Southern Africa will face similar pressures. Some will turn to piracy as environmental displacement accelerates. Without addressing climate change, environmental restoration, and equitable access to marine resources, piracy resurgence will become a recurring crisis rather than an aberration.

Finally, the connections between Somali piracy and global terrorism highlight why African security matters to the entire world. When foreign powers decline to effectively address piracy because doing so conflicts with commercial interests, they inadvertently strengthen terrorist organizations that ultimately affect global stability. The choice appears straightforward: invest now in addressing piracy’s root causes—fisheries management, coastal economic development, climate adaptation, and legitimate maritime governance—or face escalating costs as environmental and geopolitical pressures intensify.

For Somali fishing communities watching this unfold, the message is clear: powerful nations will deploy naval forces to protect international shipping but will not commit similar resources to protecting local livelihoods. International agreements come and go. Foreign powers make promises and break them. The sea remains, as it has for millennia, both a blessing and a curse for people who depend upon it.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at African Elements.