Sonya Massey Murder Conviction Reveals Deep Cracks in Police Accountability: How a “Wandering Officer” Killed a Black Woman Seeking Help

The History Behind The Headlines

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Guilty Verdict That Fell Short of Justice

On October 29, 2025, a jury in Illinois found Sean Grayson, 31, guilty of second-degree murder in the July 2024 killing of Sonya Massey, a 36-year-old Black woman shot in her own kitchen. Massey had committed no crime. She had not threatened anyone. She had simply called 911 seeking help and reported a possible prowler near her Springfield home. (CBS News) When two sheriff deputies arrived at her door early on July 6, 2024, a routine response to a routine call escalated into a tragedy that has reignited conversations about why Black Americans continue to die during interactions meant to protect them.

Grayson originally faced three counts of first-degree murder, which carries a mandatory sentence of 45 years to life imprisonment. Yet the jury delivered a conviction for the lesser charge of second-degree murder, which carries a sentence ranging from four to 20 years. Massey’s family expressed rage at the outcome. Her father, James Wilburn, asked in anguish, “He told my child he would shoot her in the F-ing face and he did it. And all we got was a second-degree murder conviction out of this?” (CBS News) The question resonated far beyond one grieving family. It reflected a bitter truth about police accountability in America: even when a killer wears a badge, justice remains elusive for Black victims.

The Killing: Boiling Water and Excessive Fear

What happened inside Massey’s home that morning reveals how quickly an encounter with police can turn fatal for Black Americans, particularly when mental health concerns intersect with law enforcement response. Massey had been grappling with mental health struggles that morning. When she called 911 to report a suspected prowler, she was seeking protection. Instead, she encountered Sean Grayson.

Deputy Farley, Grayson’s partner that night, entered the home alongside Grayson. Body camera footage from Farley recorded Massey in her kitchen, removing a pot of boiling water from the stove. As she held the pot, Massey said twice, “I rebuke you in the name of Jesus.” (Wikipedia) This statement, rooted in spiritual or religious meaning, alarmed Grayson. He screamed that he would “shoot [her] right in [her] fucking face” and drew his weapon. Then he fired three shots. One of them struck Massey just below the eye, killing her. According to witnesses, Grayson later remarked to Farley about the body, “She done. You can go get it, but that’s a head shot.” (News Channel 20) He did not attempt to provide medical aid. He discarded his medical kit, saying he would not waste his supplies. (News Channel 20)

Critically, Dawson Farley, the deputy who was present in the home, testified that he had not feared Massey. The body camera footage showed her pleading with the officers, saying, “Don’t hurt me” and “Please God.” (PBS NewsHour) Farley’s account directly contradicted Grayson’s claim that Massey posed a threat. Despite the clear threat in Grayson’s voice when he announced his intention to shoot, prosecutors argued that his actions demonstrated disregard for life. The state’s attorney told the jury, “When you threaten to shoot someone in the face, and you do, that is first-degree murder.” (ABC News)

A System Built to Fail Black Victims: The Systemic Problem

Yet the verdict was not first-degree murder. The judge allowed the jury to consider second-degree murder as an alternative, a legal option that permitted them to conclude Grayson had an unreasonable but genuine belief he was in danger. This legal pathway, while standard in Illinois, meant that Grayson’s explicit threat to shoot Massey in the face was recategorized as a situation involving potential “serious provocation.” For Massey’s family and supporters, this represented a justice system doing exactly what it was designed to do: protect the interests of those in power, even when they kill Black Americans.

What made Sonya Massey’s death particularly avoidable, however, was not just Grayson’s actions in that kitchen. It was the system that allowed him to carry a badge in the first place. Sean Grayson should never have been a police officer. His presence in law enforcement exemplifies a longstanding failure in accountability mechanisms that permits dangerous individuals to move from department to department, harming communities with impunity. Understanding how Grayson arrived at that moment reveals the deeper historical patterns that continue to endanger Black Americans.

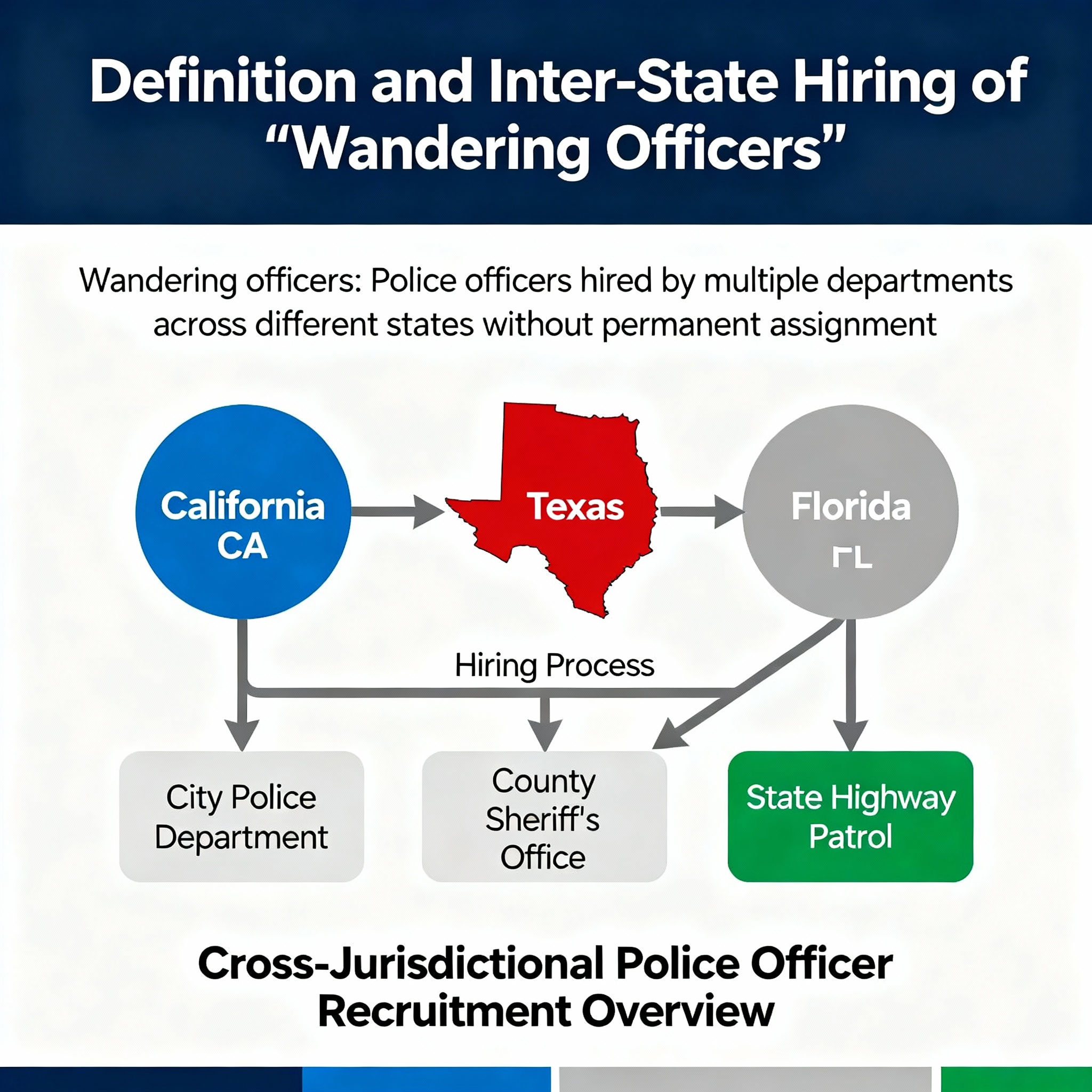

The “Wandering Officer” Problem: How Grayson Evaded Accountability

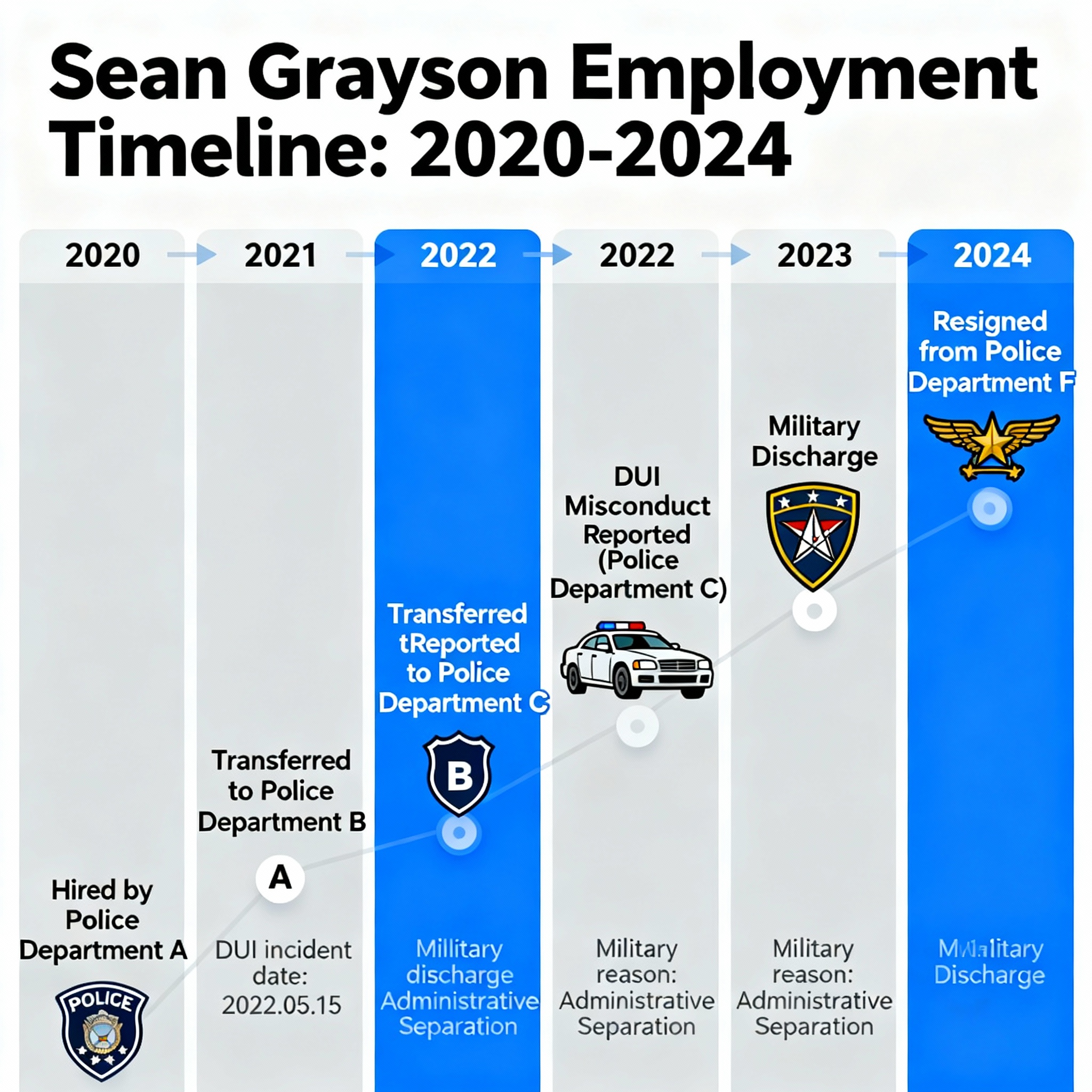

Sean Grayson worked for six different Illinois police departments in just over four years, from 2020 to 2024. (CNN) This pattern—known in policing circles as the “wandering officer” phenomenon—represents a critical failure in police hiring and vetting practices across the nation. Grayson’s employment trajectory was marked by red flags at nearly every stop, yet these warnings were repeatedly ignored or left undisclosed when he applied at the next department.

Grayson’s first problem was not in police work. Before entering law enforcement, he served in the United States Army from May 2014 to February 2016 as a wheeled vehicle mechanic at Fort Riley, Kansas. However, the Army discharged him in February 2016 for “misconduct (serious offense).” (CNN) The exact nature of this serious misconduct remained unclear for years, though records later suggested it was unrelated to a simple DUI. In 2015 and 2016, while still in the Army and after his discharge, Grayson was charged with two separate DUI offenses in Macoupin County, Illinois. (CNN) A person discharged from the military for serious misconduct and convicted twice of driving under the influence should have faced substantial obstacles to law enforcement careers. Instead, Grayson applied to police departments across Illinois.

Broken Hiring Systems: Why Grayson Got the Job

Despite his military discharge and DUI convictions, Grayson cycled through departments with alarming ease. He worked part-time for the Pawnee Police Department starting in August 2020. He then joined the Kincaid Police Department but was terminated after three months for “refusing to live within a 10-mile radius,” a basic residency requirement for the position. (KCUR) After Kincaid, he moved to the Virden Police Department, where he served for seven months. Records indicate no formal complaints or discipline during this period. Then came fuller-time employment at the Auburn Police Department from July 2021 to May 2022, followed by the Logan County Sheriff’s Office in May 2022.

It was at Logan County where Grayson’s pattern of misconduct intensified. In September 2022, Grayson was involved in a high-speed chase during which he ignored direct orders from his superiors to terminate the pursuit. He reached speeds of 110 miles per hour, turned off his lights and siren, and collided with a deer before stopping. (CNN) This incident alone should have been disqualifying. Instead, department officials simply recommended that Grayson attend “high-stress decision-making classes.” (Invisible Institute) The misconduct was never formally reported in a way that would have appeared on background checks at other departments. This is where the system failed: when officers move between departments, their misconduct often stays behind.

In May 2023, Grayson was hired by the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Office, the department where he would fatally shoot Sonya Massey. Sheriff Jack Campbell later stated that his office “understood that the serious misconduct referenced in these documents was a DUI” and that they “were aware of the DUI at the time of hire.” (CNN) Prior DUI offenses alone were deemed not disqualifying. No one at Sangamon County seemingly obtained records from Logan County detailing Grayson’s dangerous high-speed chase. The integrity complaints at Logan County, where officials concluded they had considered firing him, were not transmitted. The hiring process that welcomed Grayson into Sangamon County failed to detect what should have been obvious: he had no business carrying a badge.

Historical Roots: How Police Violence Against Black Americans Became “Normal”

Understanding why Sonya Massey died requires understanding the history of policing in America, particularly its relationship to Black communities. American police departments were not designed to protect Black people. They were designed to control them. In the South, police forces evolved directly from slave patrols that hunted enslaved people who attempted escape and terrorized free Black communities. (The National Trial Lawyers) In the North, police enforced segregation, conducted racial profiling, and participated in violence against Black residents seeking housing, employment, and basic dignity.

During the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s, police in cities like Detroit deployed violence against Black Americans fighting for justice. The Detroit Police Department, for example, operated illegally through units such as the “Red Squad,” which conducted unlawful surveillance of civil rights organizations like the NAACP and participated in the suppression of civil rights demands. (The National Trial Lawyers) When Martin Luther King Jr. declared in 1963, “We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality,” he was naming a system, not an anomaly. (The National Trial Lawyers)

Police violence against Black Americans continued into the modern era with patterns of accountability that remain deeply troubling. Research by NPR revealed that since 2015, police officers have fatally shot at least 135 unarmed Black people nationwide. At least 75 percent of the officers involved were white, and nearly 60 percent of shootings occurred in the South. (NPR) More troubling still, at least six of those officers who killed unarmed Black people were hired despite serious red flags in their backgrounds, such as drug use, domestic violence, and being fired from other departments. (Equal Justice Initiative) Several officers kept their jobs after being convicted of crimes including battery and obstruction of justice.

When Calling 911 Becomes Dangerous: Mental Health Crises and Police Response

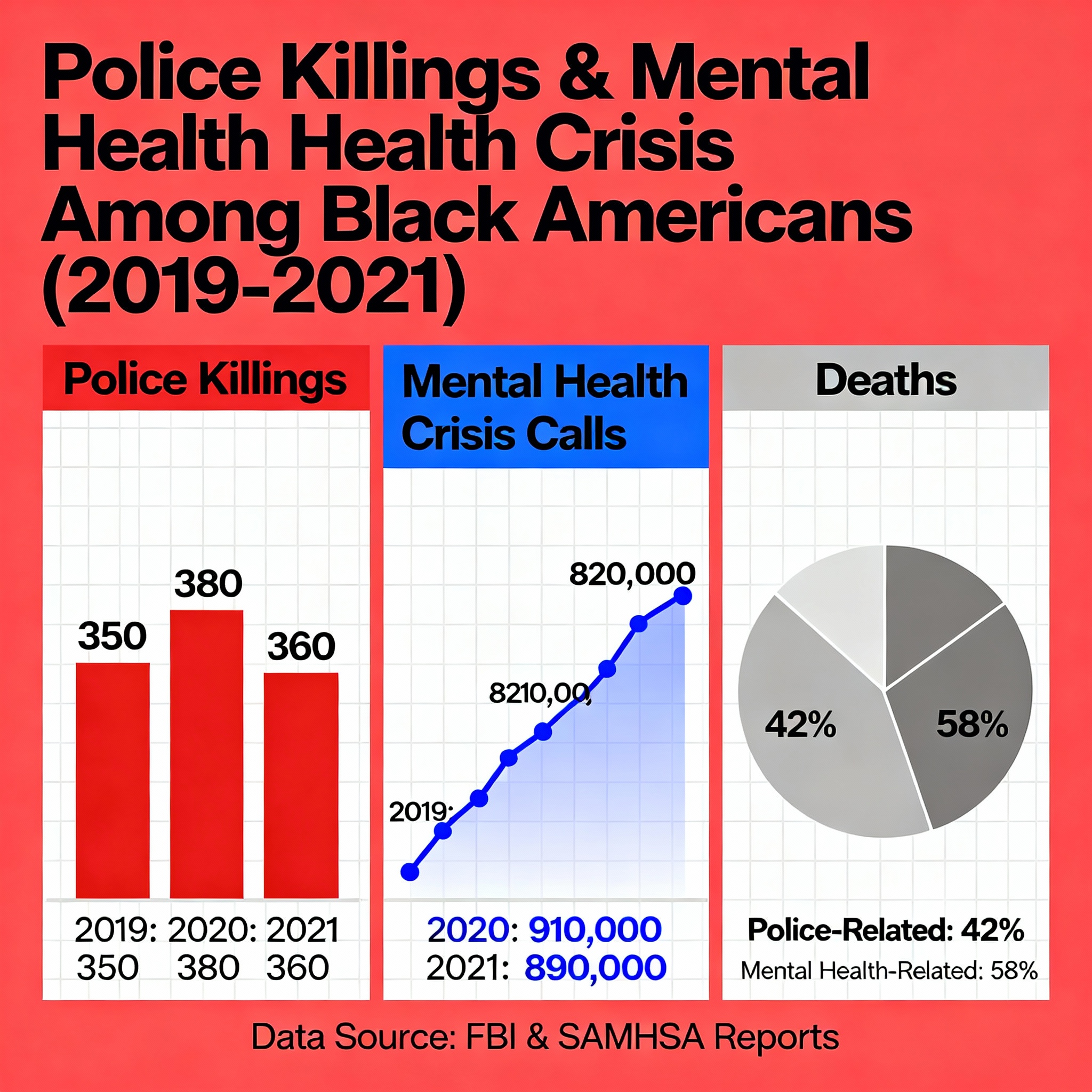

Sonya Massey called 911 for help. This fact cannot be overstated in its significance. Black Americans already live with profound mistrust of police, a mistrust rooted in centuries of justified fear. Yet when someone experiences a mental health crisis or perceives danger, the system often channels them toward law enforcement. Research by The Washington Post revealed that from 2019 to 2021, at least 178 cases resulted in law enforcement fatally shooting individuals they were called to help. (Washington Post) Many of these calls involved mental health crises, wellness checks, or suicidal ideation. Some calls came from distressed family members or friends seeking assistance for loved ones in crisis.

When police respond to mental health calls armed with lethal weapons and trained primarily in control rather than de-escalation, dangerous outcomes become statistically predictable. Massey was struggling mentally when she called for help. The officers should have been trained to recognize her distress and respond with compassion and appropriate mental health support. Instead, Grayson interpreted her spiritual language and her holding of a pot of water as threats worthy of lethal response. This response reflects not just individual failings but systemic ones. Police departments have been inadequately trained for crisis intervention and mental health response, yet they remain the primary responders to these calls in most American communities.

Qualified Immunity and the Barrier to Accountability

Even after Sonya Massey died, accountability remained limited by a doctrine most Americans have never heard of: qualified immunity. Qualified immunity is a court-created rule that limits victims of police violence and misconduct from holding officers accountable when they violate constitutional rights. (Equal Justice Initiative) The doctrine provides that a police officer cannot be put on trial for unlawful conduct unless the person suing proves not only that the conduct was unlawful, but also that the officers should have known they were violating “clearly established” law because a prior court case had already deemed similar police actions illegal. (Equal Justice Initiative)

This doctrine originated in 1967 as the Supreme Court began retreating from the Civil Rights Act of 1871, which Congress had passed to provide remedies for victims of racial violence during Reconstruction. (DC Justice Lab) The 1871 Act was specifically designed to help formerly enslaved Black people seek justice against police officers and mobs who terrorized them. Yet by the late 1960s, the Supreme Court had begun dismantling this remedy through qualified immunity. The doctrine has proven especially harmful in cases of police shootings of Black Americans. Black residents in Washington, DC, for instance, are 13 times more likely than white residents to be killed by police, yet qualified immunity has been used to prevent residents from suing. (DC Justice Lab)

The Sangamon County Settlement: Money Without Justice

In a move that some framed as accountability but that others saw as a system paying its debts, Sangamon County agreed in 2025 to pay Massey’s family $10 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit. (CBS News) This settlement represents one of the largest amounts ever paid in America for the wrongful death of a Black woman at the hands of police, according to family attorney Benjamin Crump. The payment is substantial but also reveals a troubling truth: money can settle lawsuits but cannot restore a mother to her children or bring justice in any meaningful sense.

The settlement and the conviction together represent partial accountability. They do not represent systemic change. Grayson will potentially face a sentence ranging from four to 20 years, with possible reduction for good behavior. Meanwhile, the system that allowed him to work for six police departments while accumulating misconduct and warning signs remains fundamentally unchanged, except for new legislation.

Illinois Responds: The Sonya Massey Act as a Step Toward Accountability

In August 2025, Governor JB Pritzker signed into law the Sonya Massey Act, legislation directly inspired by Massey’s death. The law mandates that police departments must share personnel records when officers apply for jobs at new departments, a basic transparency measure that should have been standard practice decades ago. (Ben Crump Law) The legislation requires local, county, and state law enforcement agencies across Illinois to conduct full background checks before hiring. Anyone applying for a police officer job must authorize all previous employers to provide complete employment records, including “duty-related physical and psychological fitness-for-duty examinations; work performance records,” and any criminal records or investigations. (CBS Chicago)

Civil rights attorneys Ben Crump and Antonio Romanucci stated, “At a time in American history when hard-fought recent police reforms are now being challenged and reversed, we applaud the Illinois legislature for taking a leadership role in commonsense policing that will better communities across the state.” (Ben Crump Law) The law passed with bipartisan support, a rarity in contemporary politics. The Sonya Massey Act represents what should have been obvious all along: if Sean Grayson’s prior employment records had been accessible to Sangamon County, if his misconduct at Logan County had been transmitted, if his discharge from the Army had been properly investigated, Sonya Massey would likely be alive today.

Massey’s father, James Wilburn, expressed hope that the law might prevent future tragedies. “It is my hope that Illinois can lead the nation in commonsense policing so that when an officer goes from department to department, their record goes with them,” he said. “We believe the Sonya Massey Law will improve the quality of law enforcement officers across Illinois who are given a badge and a gun, and that our communities will be better for it.” (Illinois Law Firm RB Law)

Why This Matters Today: A Reckoning Long Overdue

Sonya Massey was a 36-year-old Black woman who called 911 seeking help. She died in her kitchen because a police officer interpreted her spiritual language and the simple act of removing a pot of water from the stove as threats worthy of lethal response. Her death is not an isolated incident. It is part of a continuum of violence against Black Americans by police, rooted in historical systems of control and perpetuated by modern failures in accountability, hiring, mental health response, and legal protection.

The guilty verdict for Sean Grayson represents a measure of justice, but an incomplete one. The real question before Americans now is whether Sonya Massey’s death will catalyze the systemic changes necessary to prevent future deaths. Will other states adopt measures similar to the Sonya Massey Act? Will police departments nationwide implement mandatory mental health crisis training and prioritize de-escalation? Will qualified immunity be abolished or reformed? Will the nation finally confront the reality that Black Americans calling for help often encounter danger instead of safety?

These questions remain unanswered. What is certain is that until the systems that allowed Sean Grayson to wear a badge are dismantled, Black Americans will continue to live with the knowledge that a call for help might end their lives. Sonya Massey’s death exposes not just the failure of one officer or one department, but the failure of a nation to build a justice system that truly protects all its citizens equally.

About the Author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.