South Sudan Faces Catastrophic Hunger as Conflicts and Economic Collapse Threaten Millions

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at Patreon and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

When Hunger Becomes a Political Weapon

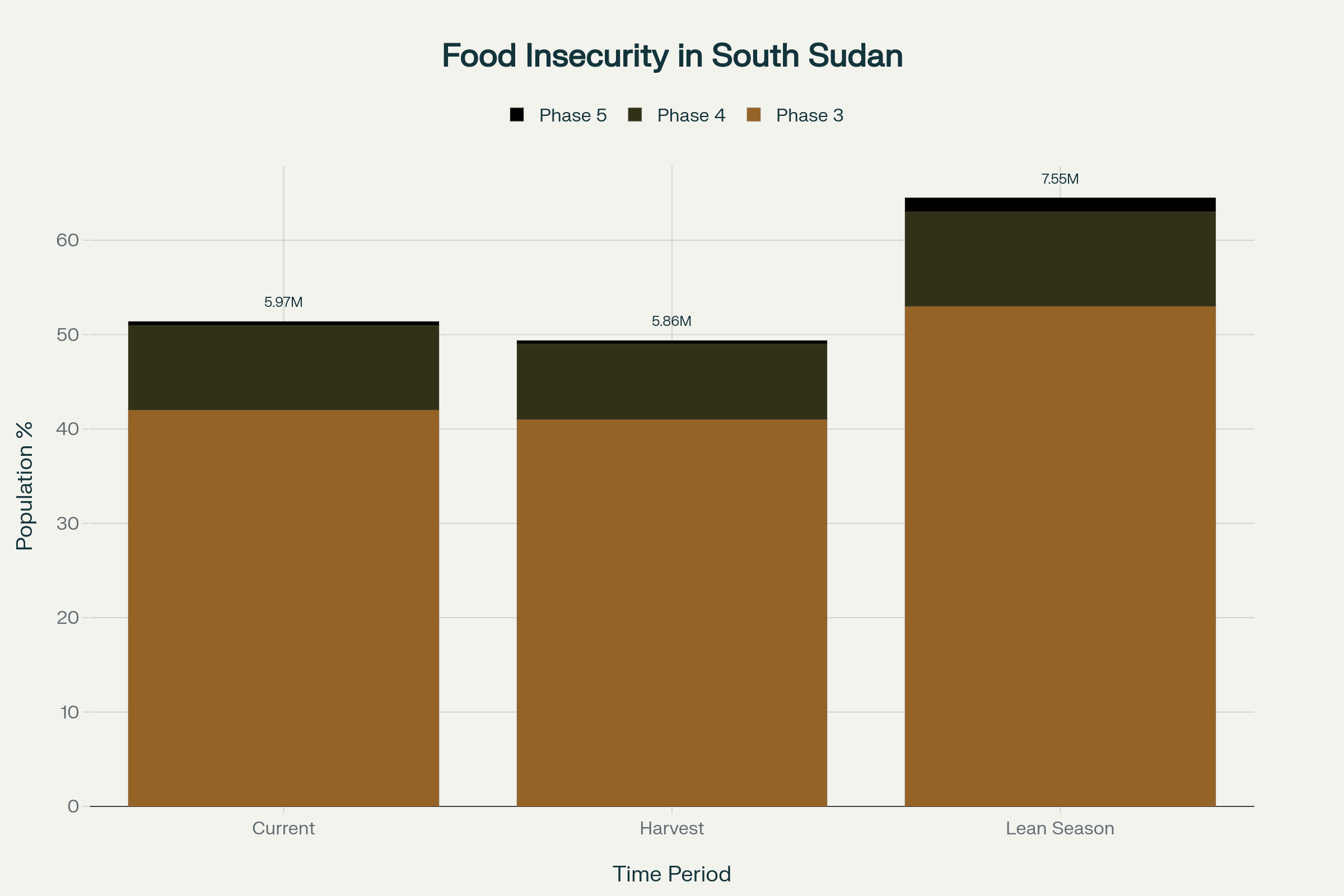

South Sudan sits at the edge of a catastrophe that African Americans and the African diaspora must understand. More than half the population—approximately 7.56 million people—will face severe hunger during the 2026 lean season from April through July. This is not a natural disaster. This is a deliberately constructed crisis driven by those in power.

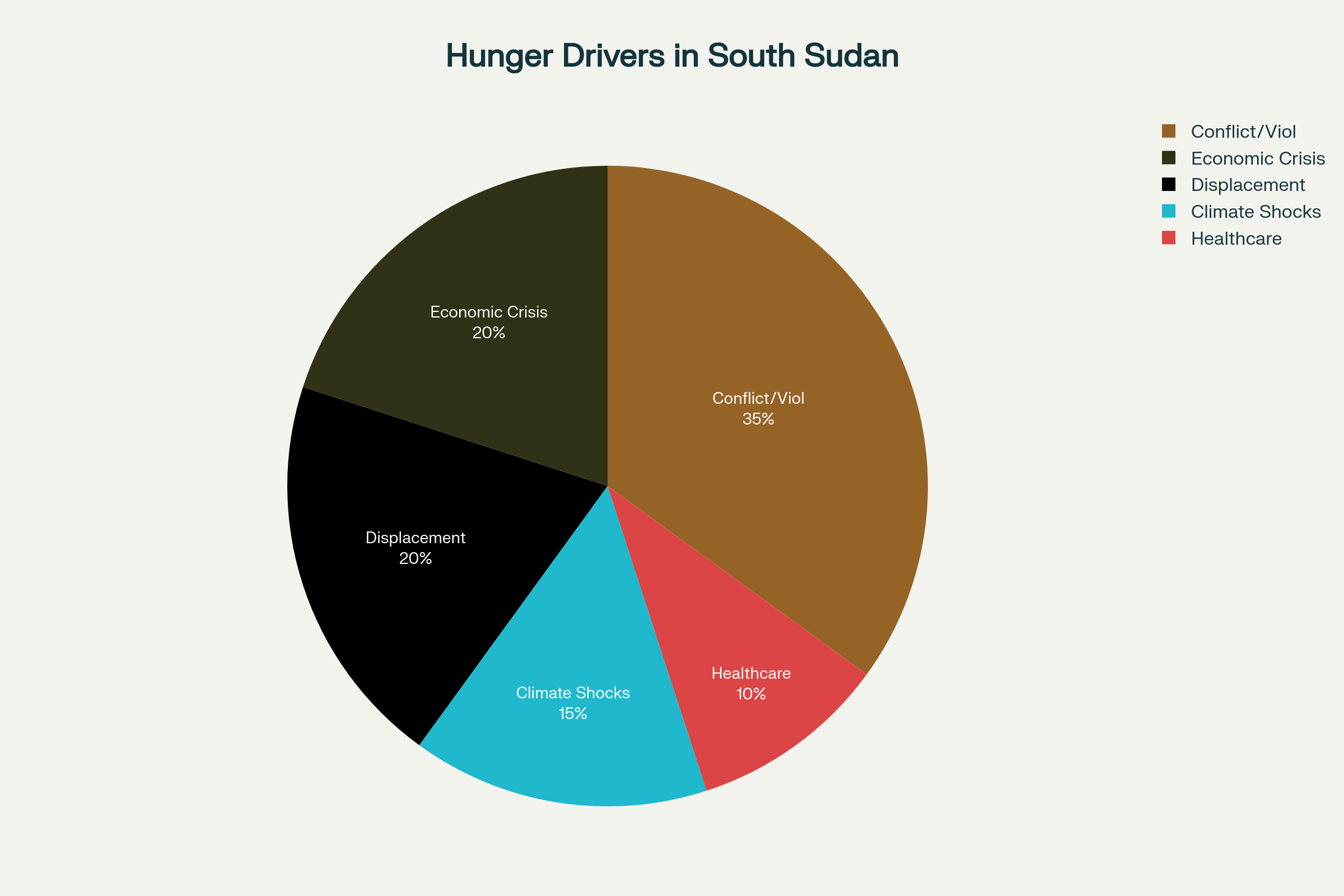

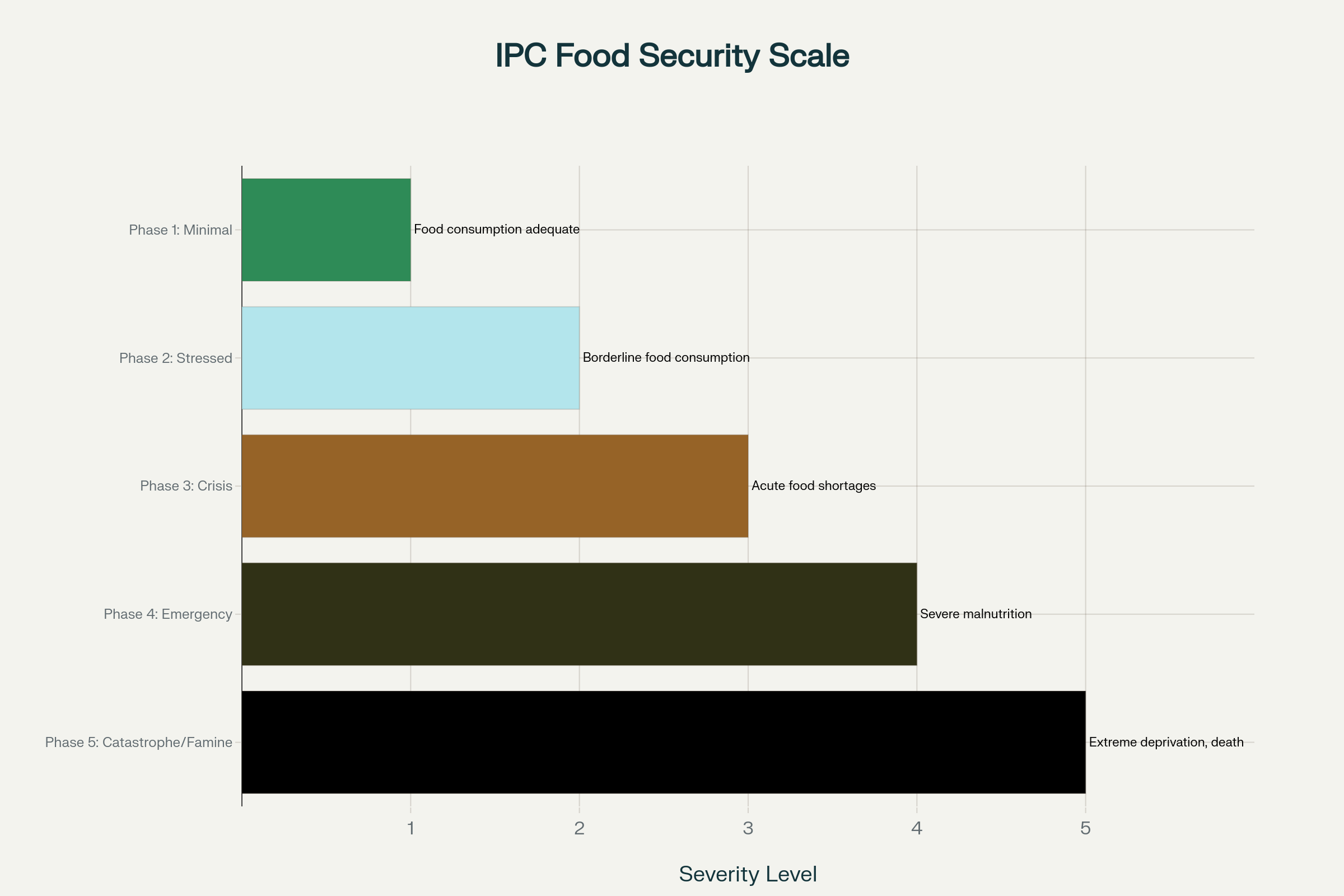

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) report released November 5, 2025 warns that violence remains the primary driver of hunger. The same pattern repeats across Africa: political leaders weaponize starvation to consolidate power, and the most vulnerable—children, women, and the rural poor—pay the price.

Current Crisis: When Half a Nation Faces Starvation

Right now, between September and November 2025, approximately 5.97 million people (42 percent of the population) face acute food insecurity. Of these millions, around 1.3 million are in Emergency (Phase 4) conditions. But the numbers get worse. Approximately 28,000 people in Luakpiny/Nasir and Fangak counties face Catastrophic (Phase 5) conditions—one step away from declared famine.

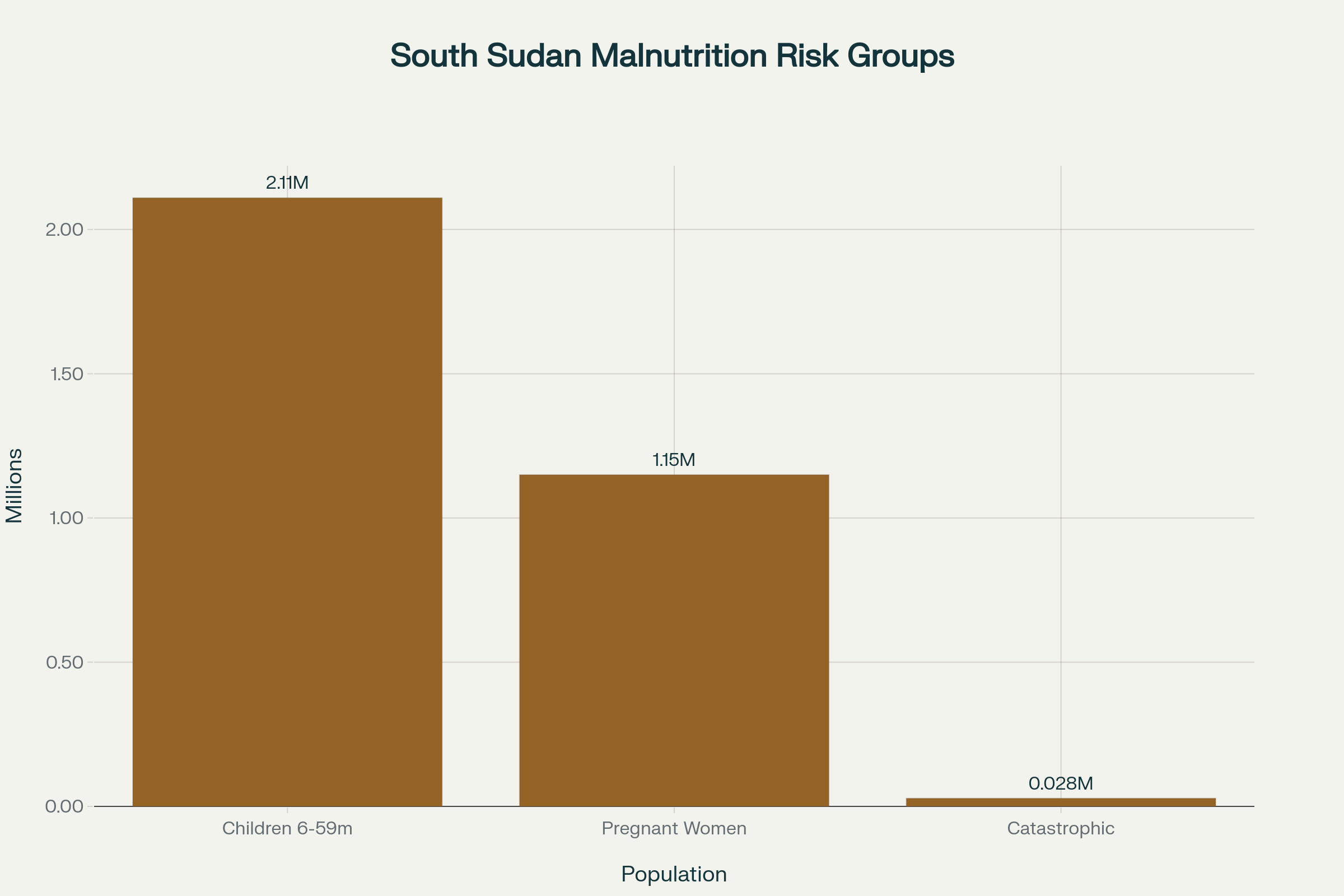

The regions most affected tell a story of how violence concentrates devastation. Over 2.1 million children aged 6-59 months and 1.15 million pregnant and breastfeeding women are expected to suffer acute malnutrition by June 2026. These are not statistics. These are Black African children and mothers whose bodies will waste away from hunger their leaders created.

The Machinery of Starvation as Strategy

FAO Representative Meshack Malo explained the brutal irony: “The hunger we are witnessing in South Sudan partly stems from disrupted agricultural seasons and agri-food systems that are sufficient to meet the country’s food needs.” South Sudan has the potential to feed itself. The problem is not scarcity. The problem is that conflict prevents farmers from reaching their fields and violence disrupts markets.

Recent battles between government forces and opposition factions have displaced entire communities. In Western Equatoria alone, 150,000 people were displaced by recent conflict. These displaced persons cannot plant crops. They cannot tend livestock. They cannot access markets. Instead, they flee with nothing—what one South Sudanese woman called “just the clothes on our backs.”

The economic collapse makes survival even more impossible. South Sudanese pound has lost nearly 95 percent of its value. Food prices have skyrocketed while wages have disappeared. In one region, nearly half a day’s wage is required just to purchase food for one family. This is deliberate impoverishment.

The Weakest Pay for the Sins of Leaders

For Black communities watching from the diaspora, the targeting of vulnerable populations should feel chillingly familiar. 2.11 million children are projected to suffer acute malnutrition. Young bodies will suffer from stunting that permanently damages their brains and bodies. Mothers will watch their children waste away. These are the costs of political conflict that their government is supposed to prevent.

Additionally, nearly 1.15 million pregnant and breastfeeding women face acute malnutrition, meaning unborn babies and infants will suffer irreversible damage. Meanwhile, those in power in Juba feast and secure their futures through weapons purchases and stolen wealth.

Centuries of Extraction: How Colonialism Built Hunger into South Sudan

The British Designed a Hungry South

To understand why South Sudan hungers today, you must understand how Britain designed hunger into South Sudan during colonization. The British did not simply occupy Sudan and South Sudan from 1899 forward. They created two completely different nations within one geography.

The British pursued a “divide-and-rule” policy that separated southern Sudanese provinces from the north and deliberately slowed their economic and social development. While the British invested heavily in the Arab north—modernizing institutions, improving education and health services—they deliberately neglected the south, claiming the region was “not ready” for the modern world.

The system was deliberate. British authorities implemented an “indirect rule” policy that fragmented southern Sudan into hundreds of informal chiefdoms, preventing an educated urban class from developing. This was not accidental. This was strategy. The British wanted no unified leadership capable of challenging their rule. They fractured southern Sudan intentionally.

Colonial Education as a Tool of Division

The condominium’s educational policies reflected this separation. In the north, the government invested in schools where Arabic and English were taught. In the south, Christian missionaries ran schools with limited resources, teaching local languages and Romanized Arabic. This was not charity. This was ensuring that southerners would have no access to the same educational and economic opportunities as northerners.

The British placed northern riverine peoples—the Shaigiyya, Jailiyyin, and Dongola groups—in positions of power and authority. These same groups continue to wield power today. By creating this hierarchy, Britain ensured centuries of conflict and marginalization that would echo forward to today’s hunger crisis.

Extractive Economies and Starving Peripheries

Colonial Sudan was designed as an extractive system. The center—the Arab north along the Nile River—was developed and enriched. The peripheries—the south, Darfur, and other regions—were drained of resources and left poor.

From colonial times, wealth and power have been concentrated in the hands of an interconnected political and economic elite composed of religious and traditional leaders, ministers, and businessmen, mostly from Arab tribes in the country’s riverine heartland. Development policies concentrated on introducing modern commercial agriculture in central Sudan while impoverished regions remained dependent on these systems. In parallel, populations in Sudan’s peripheries suffered food insecurity and famine due to political and economic marginalization, war, drought, and economic mismanagement.

This was not accidental mismanagement. This was the architecture of colonialism. Create dependency. Extract wealth. Keep populations hungry and unable to resist.

Civil War and the Making of a Famine State

The Second Sudanese Civil War: When the North Starved the South

For 22 years, from 1983 to 2005, the Second Sudanese Civil War tore through Sudan with the deliberate intent to starve the south into submission. This was not a conflict about random violence. This was systematic weaponization of hunger.

The conflict erupted in 1983 when President Gaafar Nimeiry revoked the autonomy previously granted to Southern Sudan and imposed Islamic Sharia law across the entire country. This action reignited deep-seated tensions. The response came swiftly. Under the leadership of John Garang, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) spearheaded southern resistance, fighting for self-determination, political inclusion, and an end to systematic discrimination.

The cost was devastating. Over 2 million lives were lost due to violence, famine, and disease connected to the war. This was not a war won by superior military force. This was a war deliberately prosecuted through starvation.

Famine as a Weapon of War

Historians have documented what happened. War and famine themselves have yielded benefits for central Sudan’s elite, and the ways in which production, markets, and aid are manipulated to the advantage of powerful (sometimes armed) groups remains highly relevant today. Military commanders deliberately used famine to force people off their lands, to liquidate their assets, to sell their labor for starvation wages, and to control food aid and displacement camps.

This was not poverty. This was political engineering.

The impoverishment and political marginalization of rural populations led to rebellions in the South and in Darfur and enabled the use of a militia strategy of warfare by Sudan’s former government. Impoverished Arab nomadic populations formed the backbone of militias, some members of which evolved into the Rapid Support Forces used today to terrorize civilians.

The SPLA/M promised something different. In their liberation struggle, the SPLM/A advocated for “bringing towns to the people” as liberation praxis to eliminate omnipresent hunger. They promised to break the system. They promised dignity. They promised food.

Independence and Betrayal

In 2011, after 22 years of war and decades of struggle, South Sudan became independent. The celebration lasted only two years.

In December 2013, political infighting erupted into violence when South Sudan’s president accused his vice president of an attempted coup. Fighting between government forces loyal to President Salva Kiir and those loyal to Vice President Riek Machar spread rapidly. Violence spread across the young nation like wildfire, displacing 413,000 civilians in just the first month of conflict.

The promises of liberation evaporated. The same tools of power used by northern Sudan—violence, displacement, and starvation—were now used by South Sudanese leaders against their own people. The South Sudanese elite had learned their lessons well from their colonizers.

The Pattern Repeats: South Sudan’s Unending Cycle

2017: The First Famine After Independence

By 2017, the first famine since independence was declared. In early 2017, a famine was declared in parts of South Sudan, leaving 100,000 people on the verge of starvation. This was not an aberration. This was the continuation of a pattern built by colonialism and perfected by South Sudan’s own leadership.

A famine was declared in parts of Unity State in June of 2017. The international community issued warnings. Donors pledged money. Aid organizations mobilized. Yet famine has remained a persistent threat since. This is because famine in South Sudan is not a result of environmental factors that can be easily remedied. Famine in South Sudan is structural. It is political. It is deliberate.

The 2018 Peace Deal That Never Brought Peace

A peace deal was signed in September 2018, offering false hope. While reported incidents of conflict have decreased somewhat since the new deal, the situation in South Sudan remains highly unstable and outbreaks of violence continue. This is the pattern. Violence. Peace deal. New violence. And throughout, the hungry multiply.

By 2019, 7 million South Sudanese were left hungry in the wake of conflict-related food insecurity. In 2020, the same conflicts continued. By 2021, as South Sudan approached its 10th birthday, the UN warned that the delayed peace process and drafting of a national constitution could lead to a full-scale conflict.

The warnings were correct. The cycle continued.

2025 and 2026: Catastrophe Without End

In 2025, renewed fighting broke out once again. Renewed clashes between government forces and militias loyal to Riek Machar have resulted in nearly 2,000 fatalities this year and displaced over 445,000 individuals. The displaced cannot feed themselves. Crops cannot be planted in conflict zones. Markets collapse. And now, approximately 7.56 million people are projected to face crisis or worse levels of food insecurity during April to July 2026.

This is not inevitable. This is a choice made by leaders who have learned to govern through violence and starvation.

The Current Crisis: A Perfect Storm of Deliberate Failure

Conflict Drives Hunger When Peace Allows Recovery

The evidence is undeniable. In the regions where peace has held, food security has improved. In counties where peace has been maintained, and where resources and consistent access are available, communities have begun to take their first steps toward recovery. This is the opposite of what we are told about African poverty.

We are told that Africa is too poor to feed itself. We are told that African nations simply lack capacity. But when peace exists in South Sudan, people eat. When peace disappears, people starve. The difference is not technology or capability. The difference is violence.

The government knows this. The opposition knows this. Both continue to wage war anyway. Both continue to weaponize hunger as a tool of control.

Refugees from Sudan Intensify the Crisis

In 2024 and 2025, the violence in neighboring Sudan sent over 1.1 million displaced people fleeing into South Sudan. These refugees overwhelm already fragile communities. Markets cannot absorb this demand. Resources stretch impossibly thin. And now, South Sudanese leaders point to these refugees as the cause of hunger, when the real cause is their failure to govern.

The influx of refugees and returning citizens from Sudan further strains fragile markets, overstretched services, and scarce resources. Meanwhile, the situation is especially dire for returnees fleeing violence in Sudan, who now account for nearly half of those experiencing catastrophic hunger levels.

The Broken Promise of Agricultural Potential

South Sudan has potential. The nation sits on fertile lands. South Sudan is richly endowed with fertile land and vast natural resources, yet it faces acute food insecurity. The problem is not the land. The problem is that the land cannot be used when warfare dominates.

Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood and income after the oil sector, employing two in three working women. Yet less than 5 percent of arable land is currently being cultivated because conflict prevents farmers from working their fields.

The average farm is less than 2 acres and lacks machinery. There is little access to markets, technology, or business skills development. Poor post-harvest management and inadequate soil and water management exacerbate the issue. But even these logistical challenges are secondary to the fundamental problem: violence.

Why This Matters Today for African Americans and the Global Black Diaspora

The Familiar Echo of Structural Violence

For African Americans, South Sudan’s crisis should feel familiar. The pattern—colonialism creating division and extraction, civil wars fought through starvation, leadership using hunger as a weapon—echoes through African American history and current experience.

Just as South Sudan’s poor are denied access to their own productive capacity, African Americans have been denied access to wealth-building through slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, and modern systemic racism. Just as South Sudanese leaders use violence to maintain power, American police violence maintains structural inequality. Just as hunger is weaponized in South Sudan, food insecurity is concentrated in Black American communities through discrimination in food access.

The difference in scale does not negate the pattern. Understanding South Sudan helps African Americans understand that what happens to African peoples globally is connected to what happens to us. Our liberation is bound together.

Our Responsibility to Witness and Resist

The international community has built systems to predict and prevent famines. The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification was created in 2004 to provide reliable, authoritative assessment of hunger levels. The UN has early warning systems. Donors have resources. Yet South Sudan approaches famine anyway.

This is not accident. This is choice. The choice of leaders who benefit from conflict. The choice of an international community that profits from suffering. The choice of nations that value oil and strategic positioning over the lives of Black Africans.

For the African diaspora, witnessing this and saying nothing is complicity. Speaking about it is the minimum responsibility of solidarity.

What We Can Do

Food security will not improve in South Sudan until peace is secured. Achieving lasting peace and revitalizing agri-food systems are essential to ending hunger. Peace is not something that happens by accident. It is something that must be demanded, built, and protected.

For diaspora communities, this means political pressure. It means supporting organizations that work for peace, not more weapons. It means demanding that our own governments prioritize peace-building over military aid to conflicting parties. It means recognizing that Black lives matter whether they are in America or South Sudan.

For South Sudanese communities, it means rejecting the false choice between violence and submission. It means organizing for peace and accountability. It means remembering that the promises made during liberation struggles were real and possible.

Conclusion: Hunger Will Not End Until Violence Stops

South Sudan faces a crisis that is projected to reach catastrophic levels in 2026. Over half the population will face starvation. Millions of children will suffer permanent damage from malnutrition. Mothers will watch their babies die from hunger that could have been prevented.

This is not natural. This is political. This is deliberate.

Centuries of colonialism taught South Sudan’s elites that extraction and violence pay. Recent wars taught them that hunger can be weaponized. And a fractured peace means that violence continues.

The only solution is peace. The only path to food security is ending the wars that prevent farming, destroy markets, and displace communities. The only way to honor the liberation struggle that brought South Sudan independence is to build the just society that was promised.

For the African diaspora, the crisis in South Sudan is a mirror. It shows us what happens when colonialism is not truly overcome. It shows us the cost of structural inequality when power concentrates in the hands of elites. It shows us why liberation is not a single event but an ongoing commitment to dignity, equality, and the right to eat.

South Sudan can feed itself. The land is there. The people are there. What is missing is the political will to choose people over power. Until that changes, the hunger will continue.

About the Author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at African Elements.