Listen to this article

Download AudioSpokane’s Fight Against Extreme Heat

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Spokane’s Deadly Summer Heat

In June 2021, Spokane, Washington, a city nestled near the Idaho border, faced a devastating heat wave. Temperatures soared to an alarming 109 degrees Fahrenheit (43 Celsius) and held steady for more than a week (spokesman.com). This extreme weather event had a profound impact on the community. Tragically, 19 people in Spokane County lost their lives, and approximately 300 individuals sought hospital care for heat-related illnesses (spokesman.com).

Many homes in this northern city were not built with central air conditioning, which significantly worsened the situation (spokesman.com). The vast majority of those who died during this period were in their own homes or apartments without air conditioning (spokesman.com). Many of these individuals also had underlying health conditions, making them even more vulnerable to the intense heat (spokesman.com). This tragic event served as a stark reminder of the urgent need for better preparedness and long-term solutions to protect communities from the growing threat of extreme heat.

Understanding Heat Domes and Urban Heat Islands

What is a Heat Dome?

Heat Dome: A meteorological phenomenon where a persistent ridge of high pressure traps heat over a region. This leads to prolonged periods of extreme daytime and nighttime temperatures. The 2021 heat dome in Washington State caused 157 heat-related deaths, with 19 in Spokane County. (gonzaga.edu)

The 2021 event was a “heat dome,” a term that describes an extended period of high pressure leading to dangerously high daytime and nighttime temperatures (spokesman.com). This weather pattern traps heat over a region, creating a prolonged and intense heat wave (gonzaga.edu). The 2021 heat dome in Washington State alone resulted in 157 heat-related deaths, highlighting the severe risks involved (gonzaga.edu). As climate change continues to progress, scientists warn that extreme heat events like these are expected to become more frequent and more deadly (gonzaga.edu).

What are Urban Heat Islands?

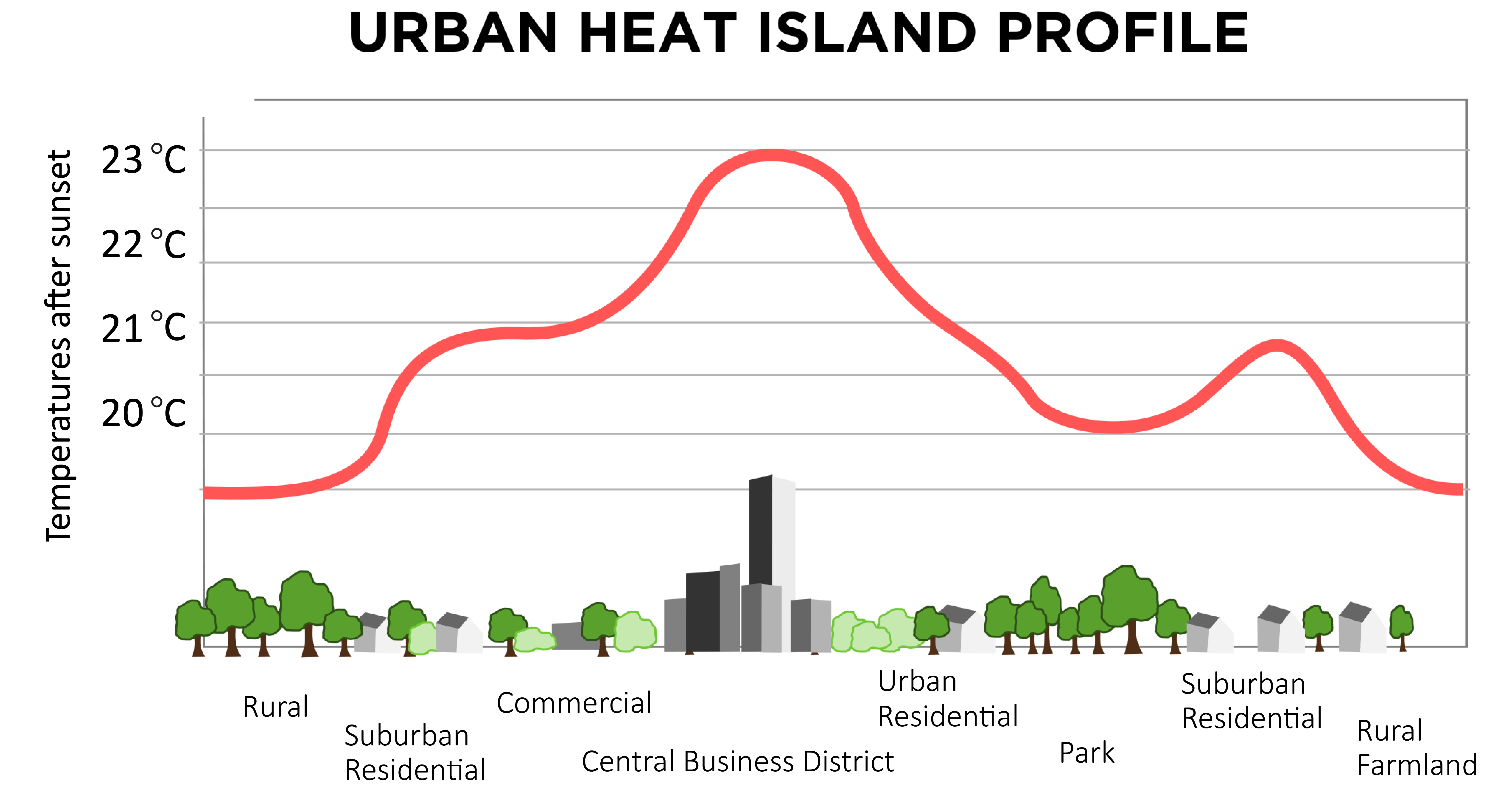

Urban Heat Islands (UHIs): Metropolitan areas that are significantly warmer than their surrounding rural areas. This temperature difference is caused by human activities and the built environment, including a lack of vegetation and increased man-made surfaces. NOAA and Gonzaga are working together to map Spokane’s urban heat islands. (nature.com, spokesman.com)

Another important concept in understanding urban heat is the “urban heat island” effect. Urban heat islands (UHIs) are metropolitan areas that are noticeably warmer than the rural areas around them (nature.com). This difference in temperature is mainly due to human activities and the way cities are built, with lots of concrete, asphalt, and buildings that absorb and trap heat (nature.com). The lack of green spaces and natural vegetation in urban areas also contributes to this warming (nature.com). Recognizing these hotter zones within a city is crucial for developing effective strategies to protect residents during heat waves.

Spokane’s Proactive Response: “Beat the Heat”

In response to the devastating 2021 heat dome, the Center for Climate launched the “Spokane Beat the Heat” initiative (spokesman.com). This program aims to help the Spokane community understand, plan for, and respond to future extreme heat events (gonzaga.edu). Its main goal is to prevent future heat-related deaths by identifying and putting into action strategies that can lessen the impact of urban heat threats (spokesman.com).

As part of these efforts, Spokane was chosen as one of 14 cities and counties across the United States for a special urban heat island mapping campaign by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (spokesman.com). NOAA provided a $10,000 grant for this important work, and Spokane was the only city in the Northwest selected for this initiative (spokesman.com). The campaign’s purpose is to identify and map the areas within the city that experience higher temperatures due to urban development (spokesman.com). This data will be vital in helping Spokane develop targeted strategies to reduce extreme heat and protect its residents (spokesman.com).

The Crucial Role of Funding and Community Preparedness

Despite these proactive steps, Spokane’s efforts to prepare for a hotter future have faced significant challenges, especially concerning funding. The city and Gonzaga University were initially awarded a substantial US$19.9 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (spokesman.com). This grant, part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, was intended to help establish resilience hubs with microgrids and assist residents without air conditioning in installing energy-efficient cooling systems (spokesman.com). However, less than a year later, the Donald Trump administration abruptly terminated this funding, along with about 350 similar grants nationwide, stating they did not align with White House priorities (spokesman.com).

This loss of funding is a major setback for Spokane, a city that cannot afford to make these crucial improvements on its own (spokesman.com). The city also lost a $48 million grant from the U.S. Department of Commerce meant to develop a tech hub (spokesman.com). These terminated grants leave Spokane’s economy and its ability to adapt to climate change uncertain (spokesman.com). A class action lawsuit has since been filed by a coalition including Earth Justice and the Southern Environmental Law Center to challenge the termination of these grants, offering a glimmer of hope for Spokane’s funding to be restored (spokesman.com).

The Impact on Spokane’s People and Future Solutions

The lack of central air conditioning in many Spokane homes significantly increases the risk of heat-related illness and death during heat waves (spokesman.com). This is especially true for vulnerable populations, including the elderly, those with underlying health conditions, and individuals living in poverty (spokesman.com). Spokane is not a wealthy area; its median household income is nearly $30,000 less than the state average (spokesman.com). More than 13 out of every 100 people in Spokane live in poverty, which is above the national average, and over 67% of the children are eligible for free or reduced lunch (spokesman.com).

Spokane’s Socioeconomic Snapshot

To address these challenges, Spokane has begun to implement measures to enhance community preparedness. During the 2021 heat wave, the city opened cooling shelters (spokesman.com). However, a key lesson learned was that temporary, or pop-up, cooling centers did not work well because people were not showing up (spokesman.com). Research suggests that a better approach is to strengthen existing community facilities that people already trust and visit regularly (spokesman.com). The Spokane City Council is considering formalizing plans for shelter space and has introduced an ordinance to set clear thresholds for enacting emergency plans in the future (spokesman.com).

Spokane’s Resilience and the Path Forward

Despite the significant financial setbacks, Spokane continues its fight for climate resilience. Beyond the initial NOAA grant, the “Beat the Heat” program has received additional support, including $10,000 in matching funds from an anonymous local donor (spokesman.com). This demonstrates a strong community commitment to addressing the dangers of extreme heat. The Spokane Climate Resilience Collaborative, a partnership between community organizations, health officials, and the city, has also formed to advance planning and response to climate hazards like extreme heat and wildfire smoke (spokesman.com).

Long-term solutions for Spokane’s heat-related issues involve developing comprehensive heat action plans that consider the changing climate (gonzaga.edu). These plans focus on managing future heat waves through strategic planning and infrastructure improvements (gonzaga.edu). The city’s housing market was predicted to thrive post-COVID-19 by housing experts (spokesman.com), and Spokane is known for its friendly neighborhoods and strong sense of community, making it welcoming for newcomers (rent.com). These existing community strengths can be leveraged to build a more resilient future. As concentrations of heat-trapping gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, both the frequency and severity of heat waves will increase, making Spokane’s ongoing efforts more critical than ever (spokesman.com).

Spokane’s Grant Funding Landscape

The lessons learned from the 2021 heat dome have galvanized Spokane to act, even in the face of significant obstacles. The city’s journey highlights the broader struggle many communities face in adapting to a changing climate, especially when federal support is inconsistent. Spokane’s story is a testament to the power of local initiatives and community partnerships in building resilience from the ground up. The ongoing efforts to map urban heat islands, strengthen community facilities, and formalize emergency plans are critical steps toward ensuring that Spokane is better prepared for the inevitable hotter days ahead.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a seasoned researcher and writer with a passion for exploring the intersections of climate, community, and social justice. With a background in environmental studies and urban planning, Darius brings a unique perspective to complex issues, focusing on how global challenges impact local communities, particularly those within the African Diaspora. His work emphasizes the importance of equitable solutions and community-led initiatives in building a more resilient future for all. Darius believes that understanding the past and present is crucial for shaping a more just and sustainable tomorrow.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.