Texas Map Ruling & Racial Gerrymandering History

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

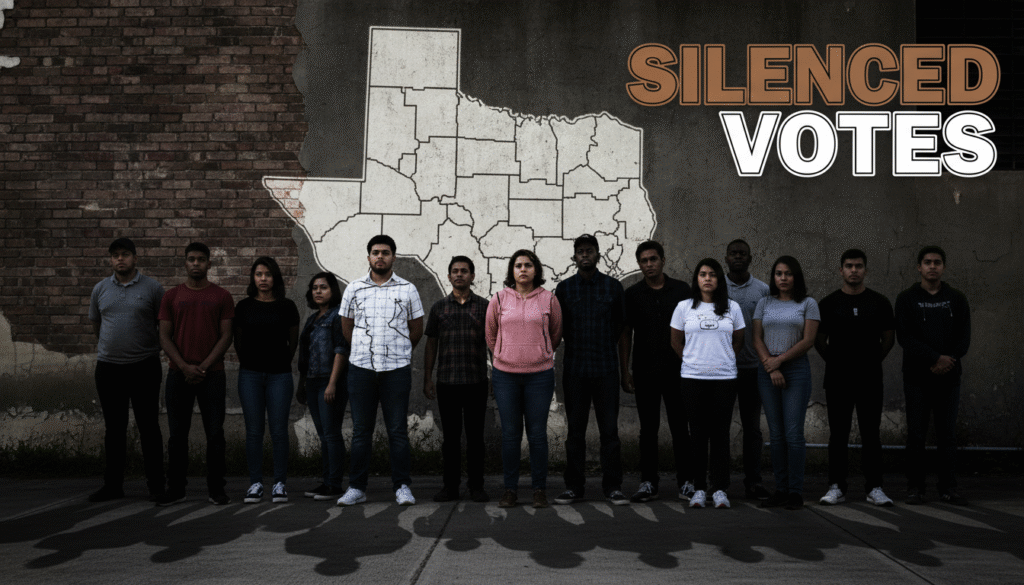

The United States Supreme Court recently greenlit a Texas congressional map for the 2026 elections, overturning a lower court’s ruling that found it unconstitutional (scotusblog.com). A three-judge federal panel had determined there was “substantial evidence” that Texas lawmakers sorted voters by race, weakening the electoral power of Black and Latino communities (pbs.org). This decision allows a map to remain that will likely secure Republican control over 30 of the state’s 38 House seats (theguardian.com). For communities of color in Texas, this ruling is not just a political setback; it is the latest battle in a generations-long war over the right to fair representation, a struggle deeply rooted in American history.

The fight over Texas’s electoral maps touches on a persistent national conflict over how district lines are drawn and their profound impact on minority voting power (scotusblog.com). While the state’s population is increasingly diverse, the political landscape is being engineered to reverse that trend in terms of representation (theguardian.com). Justice Elena Kagan, in her dissent, lamented that the court’s order permits Texas to proceed with a map found to violate “all our oft-repeated strictures about the use of race in districting” (pbs.org). This development continues a contentious legacy of manipulating electoral boundaries to silence minority voices.

The Legacy of Racial Gerrymandering

The practice of drawing electoral districts for political advantage, known as gerrymandering, is as old as the country itself. The term was coined in 1812 after Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a state senate map with a district shaped like a salamander (wikipedia.org). However, when this political tool is used to target specific racial groups, it becomes racial gerrymandering. This unconstitutional practice manipulates district boundaries to dilute the voting power of minority communities (scotusblog.com). It violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by intentionally discriminating against a racial group (wikipedia.org).

Racial gerrymandering is illegal because it involves drawing district lines where race is the primary factor, rather than legitimate considerations like geography (scotusblog.com). This is often accomplished through two key methods. “Cracking” involves splitting a minority community across several districts to ensure they do not have a significant voting bloc in any single one. “Packing” concentrates as many minority voters as possible into a few districts, limiting their influence in surrounding areas (scotusblog.com). Subsequently, both tactics effectively diminish the ability of Black and other minority voters to elect candidates who represent their interests.

A Shield Under Attack: The Voting Rights Act

For decades, the most powerful tool against racial gerrymandering was the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) (congress.gov). This landmark civil rights legislation was designed to dismantle the legal barriers that prevented African Americans from voting. Section 2 of the VRA specifically outlaws any voting practice, including redistricting, that results in the denial of the right to vote based on race (wikipedia.org). Historically, Section 5 of the act provided even stronger protection. It required certain states with a history of discrimination, like Texas, to get federal approval, or “preclearance,” before changing any voting laws (scotusblog.com).

This critical oversight was dismantled in 2013 by the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (wikipedia.org). The ruling struck down the formula used to determine which states needed preclearance, effectively gutting Section 5. Without this requirement, states can now implement new maps and voting laws without first proving they are not discriminatory. As a result, the burden has shifted to civil rights groups and individual voters, who must challenge these laws in costly and lengthy court battles after they are already in effect (scotusblog.com).

Texas’s Long War on Voters of Color

Texas has a particularly deep and troubled history of using redistricting to discriminate against minority voters. Federal courts have repeatedly intervened in the state’s map-drawing process, striking down discriminatory plans in every decade from the 1960s to the 2000s (scotusblog.com). One of the state’s past tactics involved using multi-member districts, which were found unconstitutional in the 1973 case White v. Regester for diluting the voting strength of Black and Latino communities (utexas.edu).

This pattern of discrimination continued for decades. In Bush v. Vera (1996), the Supreme Court struck down several Texas congressional districts, ruling them to be unconstitutional racial gerrymanders (scotusblog.com). The state’s actions have consistently demonstrated a willingness to manipulate electoral maps to maintain political control at the expense of minority representation. Therefore, the latest controversy surrounding the 2025 map is not an anomaly but a continuation of this long-standing practice.

Texas Demographics vs. Congressional Power

Data reflects the disparity between Texas’s diverse population and the estimated partisan control of its 38 congressional seats under the disputed map. ((census.gov), (theguardian.com))

The Disputed Map and the Court’s Ruling

The latest controversy began with an “unusual mid-decade move” by Texas lawmakers (scotusblog.com). At the urging of President Donald Trump, they redrew congressional districts outside the normal once-a-decade cycle that follows the U.S. Census (texastribune.org). Such moves are often viewed with suspicion because they suggest a political motive rather than a need to adjust for population changes (lls.edu). A lower federal court agreed, blocking the map after finding it unconstitutionally weakened the power of Black and Latino communities (pbs.org).

However, the Supreme Court intervened, granting a “stay” on the lower court’s decision (scotusblog.com). A stay is a temporary halt that prevents a ruling from taking effect while an appeal is considered (ebsco.com). In its 6-3 decision, the majority stated that Texas was likely to succeed “on the merits of its claim,” meaning its core legal arguments were strong (pbs.org). The Court also cited concerns that the lower court had committed “serious errors” and had “improperly inserted itself into an active primary campaign” (scotusblog.com). Thus, the disputed map was allowed to proceed for the 2026 elections.

Race or Party? A Legal Tightrope

Texas has defended its map by claiming it was drawn for partisan advantage, not for racial reasons (scotusblog.com). This distinction is critical in modern voting rights law. In its 2019 ruling in Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court declared that partisan gerrymandering claims are “political questions” that federal courts cannot review (wikipedia.org). However, racial gerrymandering remains illegal under the VRA and the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, which guarantees all individuals must be treated similarly under the law (scotusblog.com).

This creates a difficult challenge for civil rights advocates. When a state claims partisan intent, plaintiffs must prove that race was the “predominant factor” in drawing the district lines. When racial gerrymandering is alleged, courts apply the highest level of judicial review, known as “strict scrutiny” (wikipedia.org). This standard requires the state to prove its actions serve a compelling interest and are narrowly tailored to achieve it. Unfortunately, because race and political affiliation are often closely linked, distinguishing between partisan and racial intent can be extremely difficult, giving cover to maps that have a clear discriminatory impact (scotusblog.com).

The Math of Vote Dilution in Texas

Analysis shows the estimated number of residents it takes to elect one congressional representative by race under the disputed map. (theguardian.com)

Proving Discrimination in the Modern Era

To legally prove that a map dilutes the votes of a minority group, plaintiffs must meet the stringent criteria established in the 1986 case Thornburg v. Gingles (scotusblog.com). First, they must show the minority group is large and compact enough to form a majority in a redrawn district. Second, they must prove the group is “politically cohesive,” meaning they tend to vote for the same candidates. Finally, they must show that the white majority votes as a bloc to usually defeat the minority’s preferred candidate (wikipedia.org).

Civil rights organizations like the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) have worked to meet this high bar (maldef.org). MALDEF argued the state’s redistricting was an “unprecedented and unlawful attempt” that targeted Latino voters (independent.co.uk). A significant hurdle for these groups is a growing trend where courts, in an effort to avoid appearing partisan, demand that any alternative maps proposed as a remedy must maintain a similar partisan tilt to the illegal one (theguardian.com). This dynamic effectively prioritizes partisan outcomes over racial fairness, making it harder to dismantle maps that achieve their political goals through discriminatory means.

Source of Texas Population Growth (2010-2020)

Nearly all of Texas’s population growth over the last decade came from its rapidly diversifying communities. (texastribune.org)

The demographic reality in Texas starkly contrasts with its political map. According to the 2020 Census, communities of color account for nearly 60% of the state’s population and were responsible for 95% of its growth in the last decade (texastribune.org). Hispanic and Latino Texans now outnumber non-Hispanic white residents (censusdots.com). Yet the approved map ensures that white voters will likely decide the outcome in at least 26 of 38 congressional districts (theguardian.com).

This imbalance is staggering. Analysis shows it would take approximately 1.4 million Latino residents or 2 million Black residents to elect one representative, compared to just 445,000 white residents (theguardian.com). The Supreme Court’s decision to allow this map reinforces a political structure that does not reflect the people it governs. Ultimately, it continues a painful history where the votes of Black and Brown citizens are systematically devalued in the pursuit of political power.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.