The Grandmother Georgia Locked Up: How Mistaken Identity Reveals a System Built to Fail Black Women

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Grandmother’s Day at the Movies Became a Nightmare

On December 21, 2024, Nickie Sledge thought she was having a good day. The 49-year-old Black grandmother from Georgia spent time with her grandson at a movie theater, enjoying what should have been a normal winter afternoon. Then police showed up (11Alive). Deputies from the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office arrested her right there in front of her grandchild. They claimed she was wanted for elder abuse. The charge made no sense to Sledge. She had never abused anyone. She had no criminal record. She was a hardworking, taxpaying citizen. Moreover, she had done nothing wrong at all. Instead, law enforcement had made a stunning error that exposed how little Black women matter in a system supposedly designed to serve everyone.

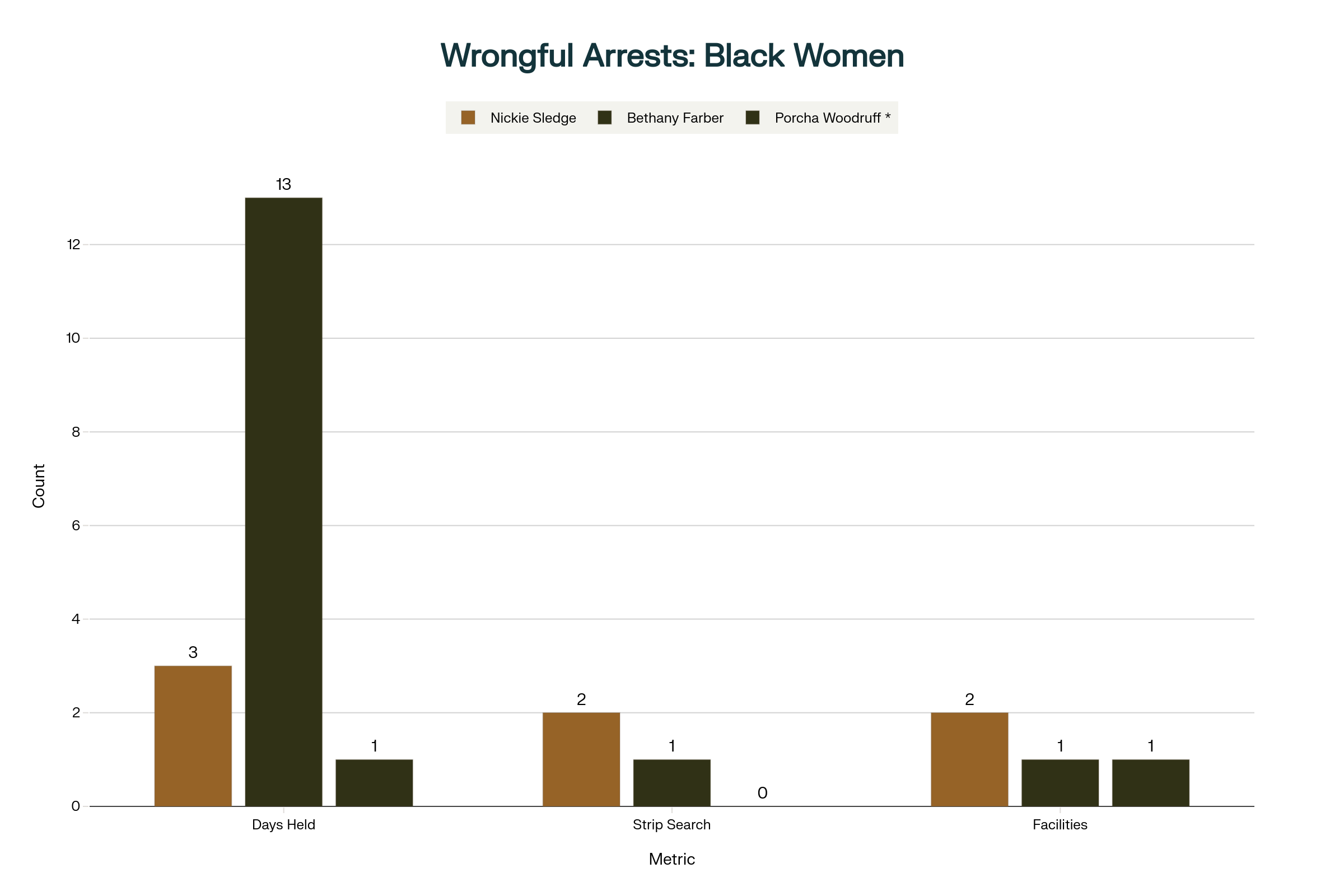

The warrant deputies carried was for a different person. It named Nikki Sledge, a 43-year-old white woman from Covington, Kentucky (Atlanta Black Star). Both women shared the same first and last name. But everything else was different. Their races were different. Their ages differed. Their home states were completely separate. Yet Cherokee County police arrested the wrong woman anyway. This was not careless. It was the result of a system that does not value accuracy when Black bodies are involved. Police took Nickie Sledge to Rockdale County Jail first, where they strip-searched her. Then they transferred her to Cherokee County Detention Center at two in the morning, where she was strip-searched a second time. Nickie Sledge spent three days behind bars for crimes committed by a white woman across state lines.

When “It’s Just a Mistake” Means Three Days in Jail

The actual suspect, white Nikki Sledge, had been accused of abusing an elderly man in Georgia. According to the case file, the couple allegedly neglected a bedridden victim while his wife was hospitalized. They allegedly used his credit card to make about \$3,500 in unauthorized purchases at Walmart (YouTube – Dumb Cops Jail the WRONG Woman). The case report even included video surveillance and photographs clearly showing the suspects were white. Police had images proving they were looking for a white woman. Yet when they encountered a Black woman with the same name, none of that mattered.

“This is a person that has no criminal record. She is a hard-working taxpaying citizen, a law-abiding citizen, and all of a sudden, on a good day, happy day, spending time with your grandchild you get arrested, you get taken away, ripped,” her attorney stated publicly (Bossip). “Your freedom of liberty is taken away, all because somebody did not do their job.” That somebody could have verified Sledge’s identity through fingerprinting. They could have checked her Social Security number. They could have looked at her date of birth. They could have compared her to the photographs in the warrant. None of this happened. Police did what they have always done when a Black body fits a name in their system: they arrested first and asked questions later.

The charges against her were dismissed in February 2025. But dismissal does not erase what happened. Nickie Sledge now carries an arrest record. That record follows her forever. Potential employers will see it. Landlords will see it. The system that got it wrong offers no real accountability (Atlanta Black Star).

When Law Enforcement Cannot Do Basic Work

This is not the first time. This pattern of failure repeats itself across America. In 2021, Bethany Farber from California was headed to Mexico through Los Angeles International Airport when TSA stopped her. Police mistakenly believed she had an outstanding warrant in Texas. Farber had never even been to Texas. She was arrested and held without bail. Police had clear ways to verify her identity. They did not use any of them. Farber spent thirteen days in jail while officers ignored her repeated requests to check her fingerprints, date of birth, or Social Security number (CNN). After her release, Farber’s grandmother suffered a stress-induced stroke and died. Farber believes the incident caused her death.

In Detroit in 2023, Porcha Woodruff was eight months pregnant when six police officers arrived at her door at dawn. They arrested her for a carjacking and robbery based on facial recognition software that had misidentified her (The Independent). The software failed to distinguish between Woodruff and the actual suspect. Even worse, Woodruff had visible differences from the mugshot police used. She had no tattoos while the actual suspect had several. Police arrested her anyway, causing her stress-induced contractions while she was heavily pregnant.

The common thread running through all these cases is the same: police cannot do basic verification work when they believe they have found the right person. This becomes exponentially worse when the person they arrest is Black.

The Deep Roots: From “Black Codes” to Modern Mistakes

The problem did not start with mistaken identity arrests. The system that allows Nickie Sledge to be arrested for a crime committed by a white woman is built on centuries of intentional racial control. To understand why she sits in jail right now, one must understand how America has always weaponized law enforcement against Black women.

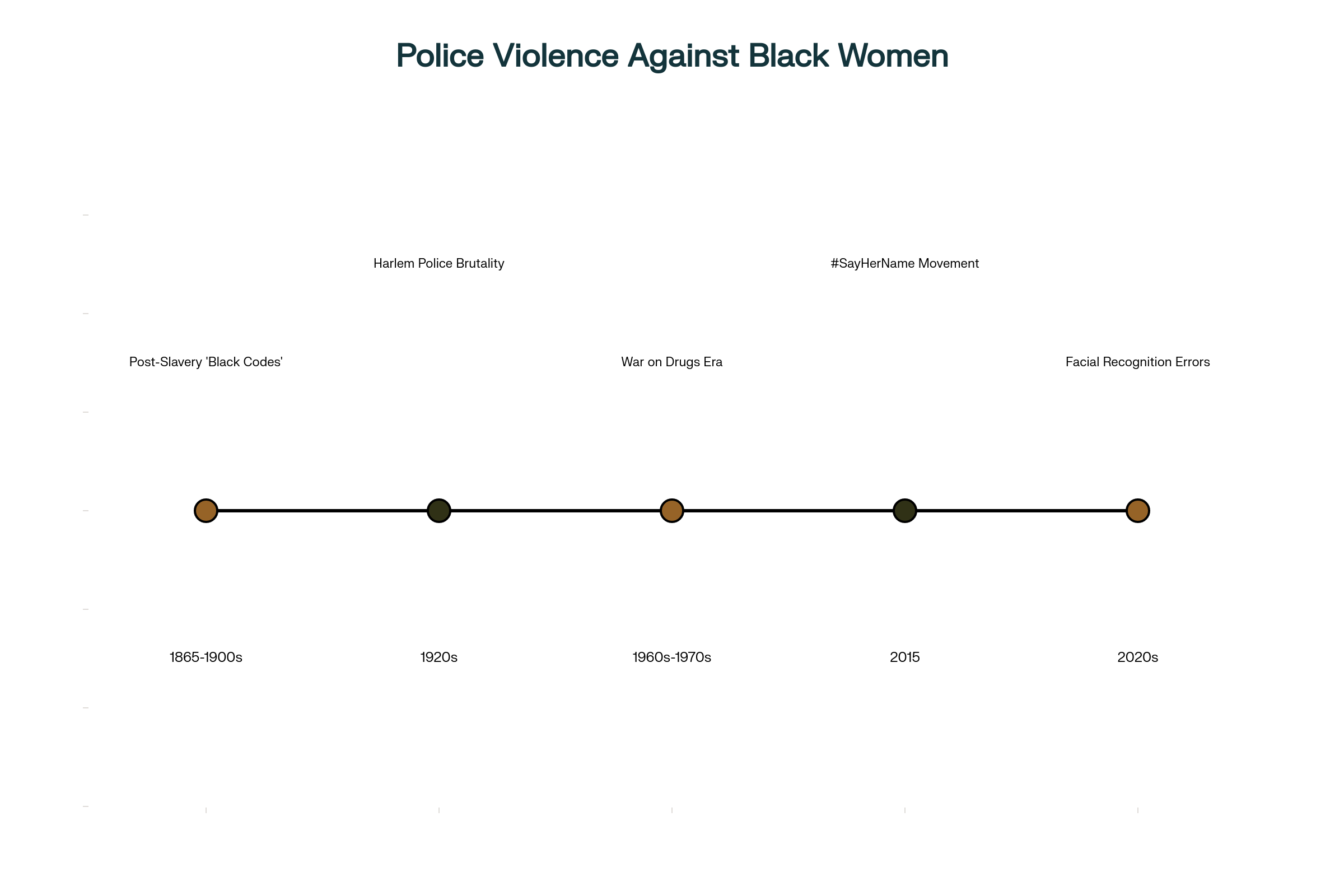

After slavery ended in 1865, Southern states created what became known as “Black Codes” (Equal Justice Initiative). These laws specifically targeted Black people and people of color for criminal arrest. They criminalized vagrancy, unemployment, and poverty. They criminalized Black behavior that white people practiced freely. Southern police enforced these laws ruthlessly, arresting unprecedented numbers of Black men, women, and children. The arrested Black people were not sent to new prisons. They were returned to slavery-like conditions through systems called convict leasing and forced labor. Black women were not protected from this system. They faced the same brutal criminalization as Black men.

By the 1920s, police violence against Black women in places like Harlem had become so severe that it prompted formal complaints (Harvard, SayHerName). Black residents reported that officers beat imprisoned women regularly. A technique called the “Third Degree” was widely used. This was essentially an “indoor lynching,” according to Black New Yorkers who experienced it. Police used the Third Degree to extract confessions through beating, sleep deprivation, and food deprivation. Black women endured this brutality alongside interrogations designed to break them. They were not treated as citizens. They were treated as targets.

The 1960s and 1970s brought what the government called the “War on Drugs,” but Black communities knew it as warfare. Police departments received military equipment, military training, and military authority. They conducted no-knock raids on Black homes. They performed strip searches and cavity searches on Black women as a matter of routine. They arrested Black women at rates completely disconnected from actual drug use but perfectly connected to where police chose to patrol (University of Michigan Law). Black women’s citizenship became irrelevant. Their humanity became irrelevant. They became collateral damage in a war declared on their communities.

When Technology Magnifies Old Racism

The twenty-first century brought new tools, but they did not bring solutions. Instead, police adopted facial recognition technology. Researchers discovered that this technology is significantly less accurate when trying to identify people of color, particularly Black people (ACLU). The algorithms were built primarily using images of white faces. Therefore, the technology performs worst on the faces it sees most often in police databases: Black faces.

Why? Because Black people are arrested more frequently than white people for the same crimes. Their faces appear more often in mugshot databases. This creates a cycle: facial recognition technology is less accurate for Black faces, which means more Black people are arrested based on false matches, which adds more Black faces to the database, which makes the technology even less accurate for future identifications (University of Michigan Law).

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, at least six people in the United States have been wrongfully arrested based on facial recognition technology errors (The Independent). All six were Black. Three of those arrests happened in Detroit alone. The technology promised to make law enforcement more accurate and fair. Instead, it made systemic racism automated. It gave racial discrimination the appearance of objectivity.

The Pattern That Proves the Problem

The National Registry of Exonerations found that in 2023 alone, 84 percent of exonerated people were people of color (Death Penalty Information Center). Nearly 61 percent were Black. These are people who were arrested, prosecuted, and convicted based on investigative failures identical to what happened to Nickie Sledge: failure to verify identity, failure to investigate thoroughly, failure to follow basic procedures. Official misconduct was the most frequent factor in their wrongful conviction.

And this affects Black women specifically. Black women face unique barriers in the criminal justice system. They receive longer prison sentences than white women for the same crimes. They are less likely to receive adequate legal defense. They are more likely to be stopped by police and arrested for minor infractions (PPIC). Law enforcement stops Black individuals differently than white individuals. When police stop white people, they are more likely to issue a warning. When police stop Black people, they are more likely to make an arrest.

These are not coincidences. These are not random mistakes. These are patterns embedded in how American law enforcement was built.

Why This Matters Today

Nickie Sledge’s arrest matters because it exposes the daily reality of Black women in America. It shows what happens when systems fail to do the most basic work: verifying that the right person is being punished for the right crime. When those systems fail, Black women end up in cells they should never have been in, separated from their families, traumatized, carrying arrest records that haunt them forever. Meanwhile, the people actually responsible for the crimes continue unpunished.

The system had multiple opportunities to get this right. Deputies could have checked Sledge’s fingerprints before booking her. They could have verified her identity through her Social Security number. They could have looked at the warrant more carefully and noticed it said the suspect was white. They could have used other identifying information besides a shared name. They chose not to do any of that. Why? Because in a system built on centuries of anti-Black racism, the default assumption is that the Black person is guilty. Verification is optional when the person accused is Black.

The arrest also matters because Sledge is planning to sue. Her attorney will likely file a civil suit against Cherokee County, seeking compensation for this “nightmare ordeal” (Atlanta Black Star). That lawsuit represents something important: a refusal to accept that such errors are inevitable, unavoidable, or acceptable. It represents the possibility that Nickie Sledge might receive actual justice, even as the person who made the mistake faces no criminal consequences.

But one lawsuit does not fix a system. The patterns documented by the Equal Justice Initiative, the ACLU, academic researchers, and civil rights organizations show that law enforcement failures affecting Black Americans are not bugs in the system. They are features. They are embedded in how American policing works. Fixing this requires more than individual lawsuits. It requires acknowledging that the system itself—built on the foundation of slavery, Black Codes, and decades of intentional discrimination—cannot be reformed. It must be transformed fundamentally.

Until that happens, there will be another grandmother arrested for crimes she did not commit. There will be another woman stripped searched for a mistake that was not hers. There will be another family traumatized by a system that never intended to serve them with fairness or justice. Nickie Sledge’s case is just one more piece of evidence that American law enforcement has a long way to go before it can claim to protect and serve all people equally.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at African Elements.