U.S. Deportation Hubs: Why Ghana is Forcing Migrants into Danger

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

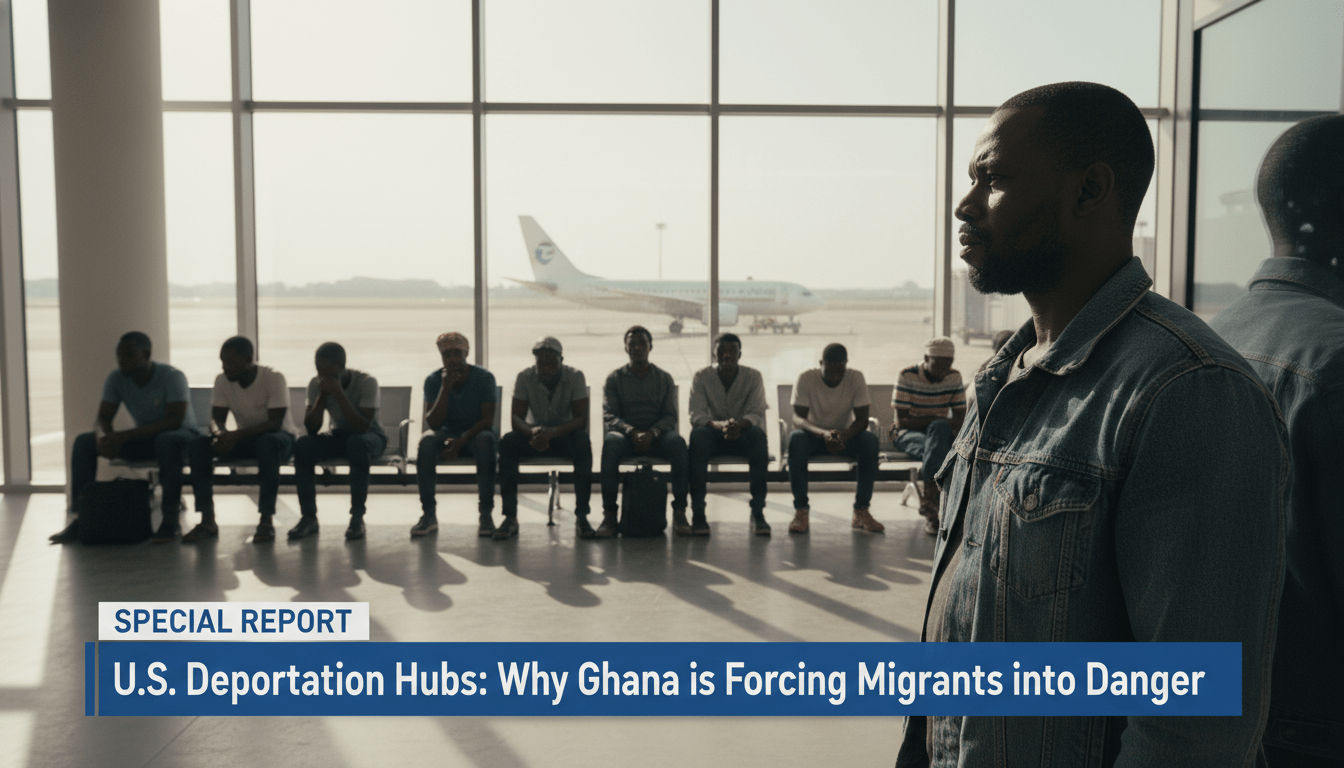

Recent headlines have exposed a disturbing trend in American immigration policy. The United States is currently sending deportees to Ghana. Many of these individuals are not even from Ghana. Once they arrive, Ghanaian officials are reportedly forcing them onward to their home countries. This process happens even when these people fear for their lives. This situation is the result of decades of changes in legal enforcement (tracreports.org).

The current crisis is not a sudden accident. It is the result of aggressive legal tools that have existed since 1952. The Trump administration has expanded these tools to create what many call a “shadow” deportation system. This system uses African nations as middle-man hubs to bypass American court protections. This strategy has deep roots in how the United States manages its borders and its relationships with foreign nations (myattorneyusa.com).

U.S. Deportations to Ghana (2021-2025)

2021: 56

2024: 94

2025: 312

Data represents Jan-Aug 2025 period only.

The Origin of the Recalcitrant Country Strategy

The foundation of this story begins with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. This law included a provision known as Section 243(d). It allows the Secretary of State to stop visa processing for certain countries. These are nations that refuse to accept their own citizens when the United States tries to deport them. For many years, this law was rarely used (tracreports.org).

The first modern application of these visa sanctions happened in 2001. The Bush administration targeted Guyana to force the return of 113 individuals. However, the shift toward making this a routine weapon occurred much later. In 2017, the Trump administration began using these sanctions more frequently. Countries like Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Eritrea faced these penalties for being “recalcitrant.” This term means the countries were stubborn about taking back their people (dhs.gov).

In 2019, the United States turned its focus toward Ghana. The American government claimed that Ghana was delaying the return of its nationals. In response, the United States imposed visa restrictions on Ghanaian citizens. Ghana argued that the United States did not provide proper proof of nationality for those being deported. These sanctions were finally lifted in 2020. This happened only after Ghana agreed to a new “repatriation roadmap” (qz.com).

This history shows a move toward using visas as a tool for leverage. The goal was to force cooperation through diplomatic pressure. This pressure has separated many kinship networks that families have built over decades. Today, that same pressure is being used to create third-country hubs. These hubs allow the United States to move people even further away from legal protection (washingtonpost.com).

From Diplomacy to Offshoring Deportations

The strategy has evolved from punishing countries to making secretive deals. This new method is called “offshoring.” It involves sending deportees to a country that is not their home. The United States first tested this model in 2019 with nations in Central America. These deals were called Asylum Cooperation Agreements. They set a precedent for sending non-citizens to third-party nations (unav.edu).

By mid-2025, this expansion reached the African continent. The United States reportedly signed deals with five African nations. These countries include Rwanda, Eswatini, South Sudan, Uganda, and Ghana. Ghana has become a primary hub for West African deportees. President John Mahama stated these deals follow regional protocols for free movement. However, human rights groups argue these deals are a way to ignore court orders (theafricareport.com).

The “hub” concept relies on something called the “Safe Third Country” designation. This legal term allows the United States to argue that an asylum seeker should have stayed in a middle-man nation. By sending a migrant to Ghana, the United States claims it has finished its job. Once the person is on Ghanaian soil, American laws no longer apply to them. This creates a legal vacuum where deportees lose their rights (mixedmigration.org).

Many activists believe these deals are done in secret. The Ghanaian government has faced accusations of bypassing its own Parliament to sign these agreements. These Memorandums of Understanding are often hidden from public view. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for families to find their loved ones. It also makes it harder for lawyers to intervene before someone is sent into danger (globalforumcdwd.org).

The Human Cost of “Forced Onward” Removals

The term “forced onward” describes a terrifying experience for many migrants. In late 2025, flights arrived in Ghana carrying non-Ghanaian West Africans. Many of these people were from Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Although they were sent to Ghana, they were not allowed to stay there. Ghanaian officials reportedly moved them to their home countries immediately (cbsnews.com).

One tragic case involves Rabbiatu Kuyateh. She is a Sierra Leonean woman who lived in the United States for 30 years. An American judge had specifically granted her protection from being sent to Sierra Leone. Despite this ruling, the government deported her to Ghana in November 2025. Six days later, officials dragged her into a van. She was then forced onto a flight to Sierra Leone (truthout.org).

Another example is Diadie Camara, a man from Mauritania. He fled his country because of hereditary slavery. This is a system where a person is born into a slave status. He was granted protection by the United States. However, the government sent him to Equatorial Guinea and then onward to Mauritania. He is now forced to live in hiding because of the danger he faces (dctransparency.com).

These actions are a violation of a principle called “non-refoulement.” This is a fundamental rule of international law. It states that a country cannot return a person to a place where they will be persecuted. By using Ghana as a hub, the United States avoids doing the “dirty work” itself. Instead, it lets other nations handle the final step of the deportation (unhcr.org).

Hereditary Slavery and the Stakes of Deportation

For individuals like Diadie Camara, deportation is more than just a change of address. In Mauritania, the stakes are matters of life and death. The country has a long history of ethnic tension. The 2023 Global Slavery Index ranks Mauritania third in the world for modern slavery. About 32 out of every 1,000 people live in hereditary slavery (neliti.com).

This system specifically targets the Haratine community, who are Black Mauritanians. Even though slavery is technically illegal, it persists in the daily lives of many. Children are born into the service of White Moor elites. When the United States deports activists who speak against this, it puts them in direct danger. Many of these people have spent years fighting for their freedom (mixedmigration.org).

The racial dynamics of these deportations cannot be ignored. Activists note that Black migrants are often treated more harshly than others. They are frequently caught in a “police-to-deportation pipeline.” This means they are more likely to be removed based on criminal records than other groups. These records often stem from biased policing in American cities (justiceforimmigrants.org).

This situation mirrors the ongoing struggle for reparations and justice for Black people worldwide. The history of forced movement is a recurring theme for the African diaspora. Today, that movement is facilitated by high-tech surveillance and diplomatic deals. The outcome remains the same: the separation of families and the return to systems of oppression (newsweek.com).

Mauritania Slavery Risk Profile

#3

● 32 per 1,000 in slavery

● Hereditary caste system

● Targets Black Haratines

The Judicial Backlash and Legal “End Runs”

American courts have begun to notice these unusual deportation tactics. In September 2025, U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan criticized the administration. She described the third-country transfers as an “end run” around the law. This term means the government is trying to bypass legal rules through a side door. She suggested the U.S. was using Ghana to avoid its own due process obligations (cbsnews.com).

The government claims it is following the law by sending people to “safe” countries. However, the definition of “safe” is very controversial. If a person is immediately kicked out of that country, they were never truly safe. This practice effectively ignores the intent of U.S. judges. It allows the executive branch to override the judicial branch by moving people out of its jurisdiction (washingtonpost.com).

Ghanaian officials use regional rules to justify their part. The ECOWAS Protocols allow West African citizens to travel within the region for 90 days. Ghana argues that it is simply following these rules when it receives deportees. Yet, these protocols were meant to help people move freely for work and trade. They were not designed to help a superpower “dump” unwanted migrants in the region (mixedmigration.org).

The use of “Dema Camp” in Ghana has also raised concerns. This is a remote facility where deportees are reportedly held. While in these camps, they have little access to lawyers or their families. This isolation makes it easier for officials to move them onward without a public outcry. It is a system designed to hide the human face of deportation (truthout.org).

The Impact on Black Families and the Diaspora

The consequences of these policies extend beyond the deportees themselves. In January 2026, the United States initiated an “indefinite pause” on visas for 75 countries. This list includes major African nations like Nigeria and Ghana. The government claims this is for public safety and vetting. However, it has a massive impact on family reunification (newsweek.com).

For many U.S. citizens in the African diaspora, this is a devastating blow. They can no longer legally bring their parents, children, or spouses to the United States. This pause acts as a collective punishment for the entire community. It discourages legal immigration and leaves families in a state of limbo. This effort is another way to suppress the growth of Black communities in America (justiceforimmigrants.org).

History shows that voter disenfranchisement and immigration control often go hand in hand. These policies limit the political power and social stability of Black families. By keeping families apart, the government weakens the community’s ability to advocate for itself. This is a systemic issue that goes far beyond simple border security (washingtonpost.com).

The Black Alliance for Just Immigration highlights these disparities. They point out that Black immigrants make up only 5.4% of the undocumented population. Yet, they represent over 20% of those facing deportation for criminal reasons. This shows that the system is not applied equally to everyone. It specifically targets those from the African diaspora (justiceforimmigrants.org).

The Road Ahead: Seeking Accountability

As the situation continues to unfold, many are calling for accountability. Legal experts argue that the United States must respect its own court orders. They say that “offshoring” is a dangerous precedent that could be used against anyone. If the government can ignore a judge by moving a person to another country, then no one is truly safe from arbitrary removal (cbsnews.com).

African nations also face pressure to stop cooperating with these deals. Activists in Ghana are asking their government to put people over politics. They argue that “Pan-African solidarity” should mean protecting those in danger. It should not mean helping a foreign power return activists to slavery or persecution. The struggle for human rights is global (theafricareport.com).

The history behind the headlines shows that this is a long-standing battle. From the INA of 1952 to the visa bans of 2026, the tools of exclusion have changed. But the target often remains the same. Understanding this history is the first step in fighting for a more just system. Families must continue to speak out and support one another in this difficult time (dctransparency.com).

Community organizations are working hard to provide resources and legal aid. They are helping families navigate the complex world of immigration law. Through education and advocacy, they aim to bring an end to “forced onward” removals. The goal is to ensure that every person is treated with dignity, regardless of their country of origin (justiceforimmigrants.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.