Why Gov Josh Shapiro Is Fighting for Slavery Truth in Philly

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

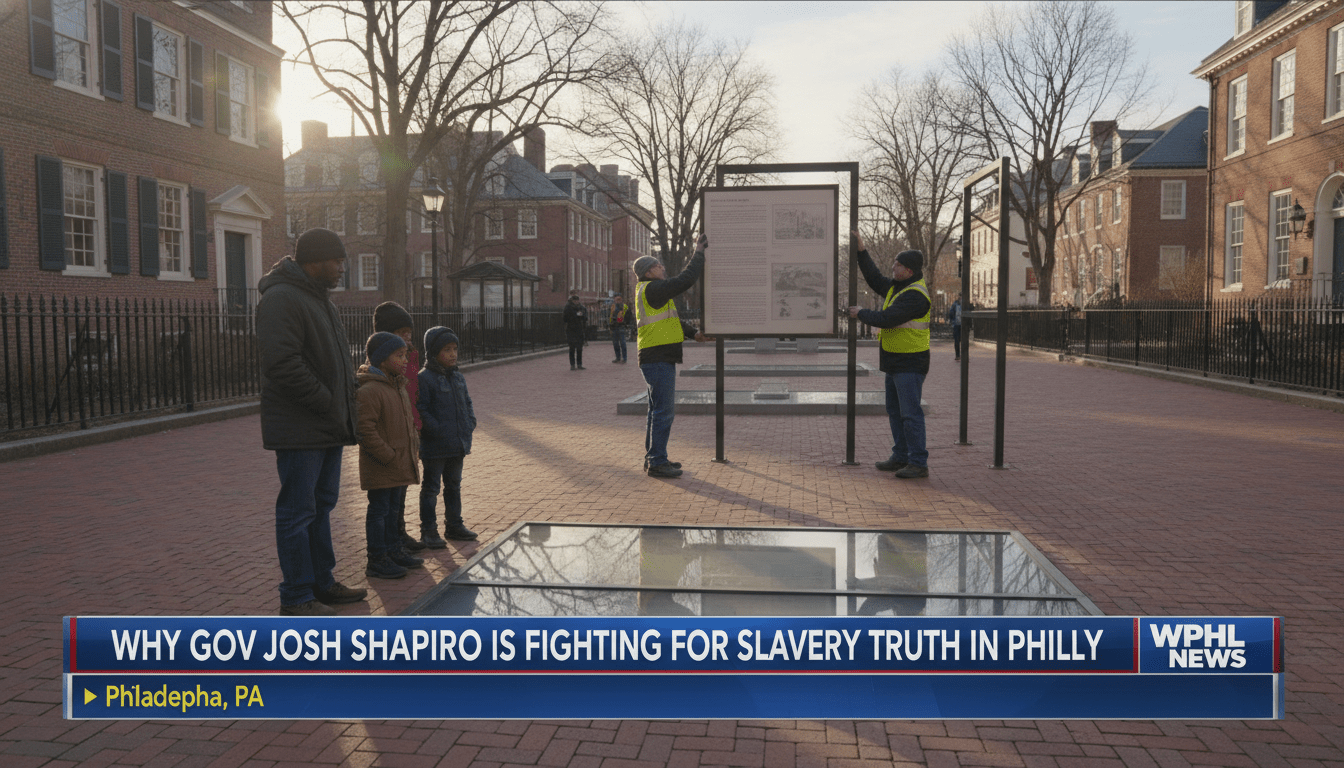

The streets of Philadelphia are often quiet in the early morning of January. On January 22, 2026, however, the silence at Independence National Historical Park was broken by the sound of tools. Workers from the National Park Service began to take down educational signs. These signs told the story of the enslaved people who lived at the home of George Washington. This action has sparked a massive legal fight led by Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro (phillyvoice.com, cbsnews.com).

Governor Shapiro has promised to take the federal government to court. He argues that removing these displays is an attempt to rewrite and whitewash the history of the United States. The Governor stated that Pennsylvania learns from its history even when that history is painful. This conflict is about more than just signs on a wall. It is a battle over who gets to tell the story of America and how the nation remembers its founding (theguardian.com, cityandstatepa.com).

The President’s House Enslavement Reality

Enslaved People at Mount Vernon (316)

Enslaved People in Philadelphia (9)

Data source: Research on Washington’s enslaved staff (ushistory.org, nps.gov)

The Paradox of Liberty at the Executive Mansion

To understand why this fight is so intense, one must look back to the year 1790. At that time, Philadelphia served as the temporary capital of the new nation. President George Washington lived in a mansion at 6th and Market Streets. This site is now known as the President’s House. While Washington was leading a country built on the idea of freedom, he was also a slaveholder. He brought at least nine enslaved African descendants to live with him in Philadelphia (ushistory.org, nps.gov).

The names of these individuals are Oney Judge, Hercules Posey, Richmond, Giles, Paris, Austin, Moll, Joe, and Christopher Sheels. Their presence created a deep contradiction. They lived just a few feet away from where the U.S. Constitution and slavery were being debated. Washington faced a legal problem in Pennsylvania. The state had passed the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780. This law said that any enslaved person who lived in the state for six months would become free (wikipedia.org, ushistory.org).

President Washington used a legal maneuver to keep these people in bondage. He would rotate his enslaved workers back to Mount Vernon in Virginia every six months. This action restarted their “clocks” and prevented them from gaining their legal freedom under Pennsylvania law. This history shows how the highest office in the land worked to maintain the institution of slavery while claiming to support liberty. It is this “paradox of liberty” that the now-removed exhibit was designed to explain to the public (nps.gov, betweenerrors.com).

The Long Road to the 2010 Memorial

For over 150 years, the history of the President’s House was largely forgotten. The building was torn down in 1832. In 2002, a historian named Edward Lawler Jr. published research that changed everything. He discovered that the new Liberty Bell Center was being built directly over the footprint of the quarters where the enslaved people lived. This news caused a massive public outcry in Philadelphia (wikipedia.org, journalpanorama.org).

A group called the Avenging The Ancestors Coalition (ATAC) led the charge for recognition. They demanded that the National Park Service tell the whole truth about the site. They did not want the history of slavery to be hidden behind the story of the Liberty Bell. After years of protests and community meetings, the city and the federal government agreed to build a memorial. The $8.5 million open-air exhibit opened in 2010 (wikipedia.org, inquirer.com).

This exhibit was the only federal historic site specifically dedicated to the paradox of slavery and freedom at the nation’s founding. It featured biographical panels and videos that humanized the nine enslaved individuals. Visitors could see the archaeological ruins of the house and read about the lives of those who were held captive there. It became a place of “public truth” where the struggle for freedom was presented as a central part of the American story (revolt.tv, hyperallergic.com).

Timeline of the Removal Crisis

President Trump and the Order to Remove Content

The recent removal of these signs did not happen by accident. It was the result of a policy change at the highest level of government. In March 2025, President Donald Trump signed Executive Order 14253, titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History.” This order directed federal agencies to remove any content that “inappropriately disparages” historical figures from the American past (theguardian.com, pen.org).

The Department of the Interior conducted a review of National Park Service materials. They decided that the displays at the President’s House promoted “divisive narratives.” They argued that focusing on the “horrors of slavery” cast the Founding Fathers in an inappropriately negative light. According to the federal government, public sites should focus on “shared national values” and the “greatness of the achievements” of the American people (pen.org, cair.com).

Critics describe this move as a clear case of whitewashing. In a social justice context, whitewashing means altering historical facts to make injustices more palatable to the dominant culture. It often involves ignoring the experiences of people of color to create a more “idealized” national identity. By removing the panels, the government is effectively making the lives of the nine enslaved people “barely exist” in the official record once again (theguardian.com, independent.co.uk).

Governor Shapiro’s Legal Battle for History

Governor Josh Shapiro has positioned Pennsylvania at the forefront of the resistance against this federal order. He has pledged the full weight of the Commonwealth’s legal resources to fight the removal. Shapiro argues that a nation cannot be strong if it is afraid of its own history. He believes that telling the truth about slavery is necessary for the public to understand the full meaning of democracy (phillyvoice.com, cityandstatepa.com).

The legal fight is not just about words; it is about a breach of contract. The City of Philadelphia filed a federal lawsuit against Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and the National Park Service. The city points to a 2006 Cooperative Agreement. This contract mandates that any changes to the exhibit must be made through mutual consultation between the city and the federal government (cityandstatepa.com, jurist.org).

The lawsuit also claims that the National Park Service violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The APA is a federal law that prevents agencies from taking “arbitrary and capricious” actions. The city argues that removing the exhibit overnight without a public comment period or a reasoned explanation is illegal. This legal challenge aims to stop the removal and restore the educational content before the nation’s 250th-anniversary celebrations in July 2026 (jurist.org, villagevoicenews.com).

Public Preservation Interest

Images Submitted for Indy Park

Total National Submissions

Submissions to the “Save Our Signs” initiative (hyperallergic.com, theartnewspaper.com)

The Lives Behind the Removed Panels

The panels that were removed told the specific stories of people like Oney Judge and Hercules Posey. Oney Judge was an enslaved woman who escaped from the President’s House in 1796. She fled to New Hampshire and lived the rest of her life as a fugitive, refusing to return even when Washington sent agents to find her. Her story is a powerful example of agency and resistance (theguardian.com, nps.gov).

Hercules Posey was Washington’s celebrated chef. He was famous in Philadelphia for his culinary skills. On Washington’s 65th birthday, Hercules also chose freedom and escaped. These individuals were not just “names on a list.” They were people who fought for their own liberty while living in the shadow of the man who led the fight for American independence. The removal of their stories is seen by many as a second “erasure” of their existence (theguardian.com, nps.gov).

Other individuals mentioned in the exhibit also had tragic and complex lives. Austin, the half-brother of Oney Judge, died after a fall from a horse while serving the President. Christopher Sheels was a literate personal attendant who attempted an escape that was foiled by Washington. He was present at Washington’s deathbed, still held in bondage. These stories provide educational resources that help people understand the lived reality of enslavement (nps.gov, betweenerrors.com).

The Significance of the Footprint

One of the most powerful parts of the President’s House site is the physical “footprint” of the enslaved people’s quarters. This footprint is located only five feet away from the entrance of the Liberty Bell Center. This means that every person who goes to see the symbol of American freedom must physically walk over the ground where people were enslaved. This proximity forces a direct confrontation with the truth of the American founding (ushistory.org, nps.gov).

For activists like the Avenging The Ancestors Coalition, the footprint is a permanent stamp on the land. They argue that the National Park Service cannot separate the history of slavery from the history of the presidency. Even though the interpretive panels have been taken away, the archaeological ruins and the names etched in stone remain. These physical remains serve as a “stubborn testament” to the lives of the nine people who were held there (wikipedia.org, inquirer.com).

Since the removal of the official signs, protesters have begun to leave their own markers. Hand-lettered signs and flowers now sit where the professional displays once stood. This grassroots effort shows that the public is not willing to let this history disappear. The site continues to be a place where the conflicting elements of American identity are debated every day (revolt.tv, hyperallergic.com).

The Fight for Public Memory and Truth

The battle over the President’s House exhibit is a reflection of a larger national struggle. On one side, the federal government wants to promote a narrative of “American exceptionalism” that minimizes past failures. On the other side, state leaders like Governor Shapiro and local activists demand an honest accounting of the past. They believe that true patriotism requires acknowledging both the triumphs and the tragedies of the nation (theguardian.com, wsws.org).

This fight is especially important as the country approaches the year 2026. Philadelphia will be the center of the world’s attention during the 250th-anniversary celebrations. The question remains: what kind of history will the millions of visitors see? Will they see a sanitized version of the past, or will they see the full, complicated truth of how America was made? The outcome of Governor Shapiro’s lawsuit will likely decide the answer to that question (hyperallergic.com, cityandstatepa.com).

Preserving history is not about making people feel bad about the past. It is about providing the tools for future generations to build a better country. By standing up for the slavery exhibit, Governor Shapiro is asserting that the lives of those who were enslaved are just as important to the American story as the lives of the presidents who held them. This battle for public truth is a fight for the soul of American memory (revolt.tv, eji.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.