Why Lagos Forced Evictions and Human Rights Violations Continue

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

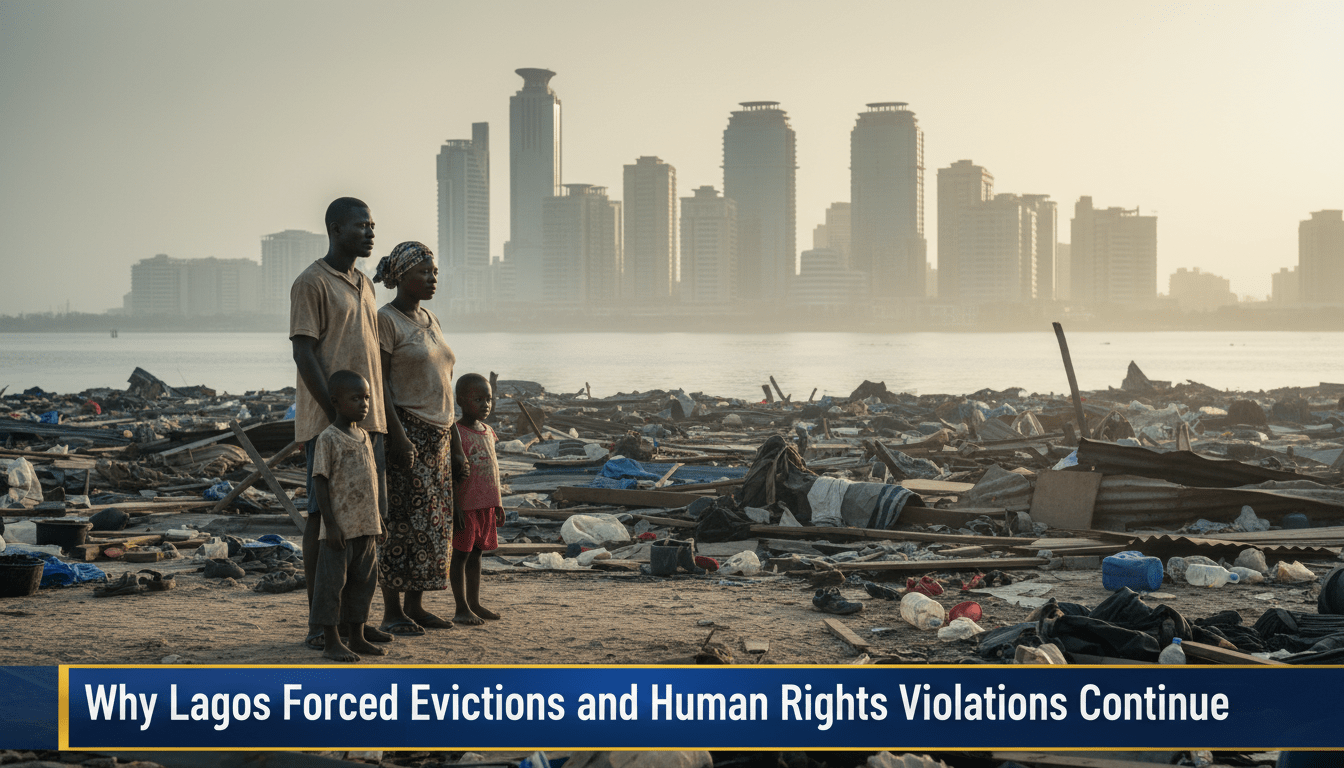

In February 2026, the international community turned its gaze toward Nigeria with deep concern. United Nations human rights experts issued a strong condemnation of the mass demolitions taking place in Lagos. They warned that a ruthless campaign of forced evictions is creating a human rights crisis for thousands of residents (ohchr.org). This news serves as a painful reminder of the struggles faced by Black communities globally. For many in the Diaspora, the destruction of homes in the name of progress is a familiar story. It echoes a history of displacement that spans decades and continents.

The recent headlines focus on the immediate suffering of families. However, these events are part of a much larger pattern of urban development. This strategy has long traded the safety of the poor for the luxury of the elite. To understand the current crisis, one must look back at a 50-year history. This history shows how the city uses the homes of the vulnerable to build its “megacity” dreams. The experts warn that these actions may even constitute a grave international crime known as domicide (ohchr.org).

The Long History of the Eviction Playbook

Lagos has a long track record of clearing out poor neighborhoods to make room for high-end real estate. Since the 1970s, the state has balanced its ambitions on the backs of its most vulnerable citizens (issafrica.org). One of the most famous examples occurred in July 1990 with the eviction of Maroko. During that single military operation, the government displaced at least 300,000 people from their homes. Officials claimed the move was for environmental reasons. Yet, the land soon became the high-brow Victoria Island and Oniru Estate (issafrica.org).

This event established what many call the “eviction playbook.” First, the state labels an area as blighted or unsafe. They often cite flooding risks or a lack of proper permits. Once the residents are gone, the land is reclaimed and sold to wealthy developers. Former residents never get the chance to live in the new luxury buildings. This pattern repeated in Makoko in 2005 and 2012. It also happened in Badia East in 2013 (issafrica.org). The cycle of displacement has become a permanent feature of the urban landscape.

Timeline of Major Lagos Displacements

1990: Maroko

300,000 people displaced for Victoria Island.

2016: Otodo-Gbame

30,000 residents evicted; homes burned.

2023-2025: Current Wave

Acceleration of waterfront removals.

2026: UN Condemnation

Experts warn of “domicide” in Makoko.

The Violent Reality of Forced Evictions

The methods used in these evictions are often brutal. In 2016 and 2017, the world watched the Otodo-Gbame massacre. Security forces burned the waterfront community to the ground. This happened despite a court order that protected the residents (issafrica.org). Thousands of people were forced into the lagoon to escape the flames. Several people, including children, drowned during the chaos. The state justified the violence by citing security and environmental safety. However, many saw it as a blatant land grab for luxury development.

The current wave of demolitions in 2026 is no less severe. UN Special Rapporteurs Balakrishnan Rajagopal and Paula Gaviria pointed out the systematic nature of these acts (ohchr.org). In Makoko, between December 2025 and January 2026, over 3,000 homes were destroyed. This left more than 10,000 people without shelter (ohchr.org, punchng.com). Local groups reported that at least 12 people died during these recent operations. Among the dead were two infants. These statistics highlight the deep human cost of urban renewal policies that ignore the rights of the poor.

Understanding Domicide in the Modern City

The term “domicide” is being used by UN experts to describe the situation in Lagos. Domicide refers to the deliberate and systematic destruction of homes (ohchr.org). It is not just about the physical loss of a building. It involves the destruction of the social fabric and the sense of place of a community. Experts argue that governments use administrative excuses to permanently remove marginalized populations. This is often seen as a form of “class-cleansing” in rapidly growing global cities (ohchr.org).

In Lagos, the destruction includes more than houses. Schools, clinics, and religious centers are also razed. This strips residents of their right to education and health. For the people of Makoko, their entire way of life is under threat. As the world’s largest floating village, their culture is tied to the water. When their homes are destroyed, their livelihood in fishing is also lost (ohchr.org). The UN argues that these are not simple planning errors. They are systematic violations of international law that target the most vulnerable (ohchr.org).

Projected Housing Deficit (2025-2026)

The Bureaucracy of Dispossession

The Lagos State Government uses specific language to justify its actions. They often refer to demolitions as the "removal of contraventions" (premiumtimesng.com). This is a bureaucratic term for structures that violate urban planning laws or lack proper permits. Under Nigerian law, any building without an official "Letter of Allocation" can be considered a contravention (thenationonlineng.net). This allows the state to clear land without providing any compensation to the owners. Human rights groups argue that this law is used selectively (thenationonlineng.net).

While the state targets informal settlements, luxury developments often go unpunished. Many of these high-end buildings are constructed in similar zones. The 1978 Land Use Act gives the Governor immense power over all land in the state. This law allows the state to revoke occupancy rights for the "overriding public interest" (issafrica.org, thenationonlineng.net). In many cases, this interest seems to align more with private developers than with the public good. This power imbalance makes it difficult for residents to defend their homes in court.

This struggle for land is not unique to Nigeria. It mirrors the political shift from civil rights to mass incarceration seen in other nations. In the United States, urban renewal programs in the 20th century were often called "Negro Removal." Both systems use "blight" as a label to devalue property before the state takes it. The destruction of Black neighborhoods for highways or parks in America finds a direct parallel in Lagosian waterfront clearances.

Internally Displaced Persons in Their Own Land

The victims of these demolitions are classified as Internally Displaced Persons, or IDPs. These are people forced to flee their homes who remain within their country's borders (ohchr.org). Unlike refugees, IDPs do not cross international lines. They are technically under the protection of their own government. However, in Lagos, the government is often the cause of their displacement. This creates a difficult situation where the protector is also the persecutor.

When residents are evicted, they often lose access to all basic services. They lose their community ties and their proximity to work. Because they stay within Nigeria, they lack a dedicated international treaty to protect them. They often end up moving to other informal settlements that are even more precarious (issafrica.org). This leads to a cycle of "slumification" rather than solving the housing crisis. Instead of improving living conditions, the state simply moves the problem to a new location.

The Environmental Cost of Land Reclamation

A major driver of displacement in Lagos is the process of sand-filling. This involves dredging sand from the lagoon to create new land for construction (issafrica.org). This process has created high-value areas like Eko Atlantic. While it creates land for the wealthy, it destroys the natural environment. Sand-filling removes mangrove forests that protect the city from storm surges. It also increases flooding in neighboring low-income areas (issafrica.org).

As water is displaced from new luxury sites, it is pushed into unprotected communities like Makoko. This makes these neighborhoods more dangerous and gives the state a reason to clear them. Environmentalists warn that this approach is unsustainable. It destroys fish breeding grounds and ruins the livelihoods of local fishermen (issafrica.org). The focus on creating "modern" land often ignores the ecological and social health of the lagoon. This short-term gain for developers creates long-term risks for the entire city.

Seeking a Global Megacity Status

Lagos is driven by the desire to be a "Global Megacity." A megacity is defined as a metropolitan area with over 10 million people. Lagos has more than 20 million residents. To attract foreign investment, the state follows a master plan modeled after cities like Dubai. This plan often prioritizes aesthetics over the needs of current residents. Officials view stilt houses and informal markets as obstacles to a modern image (issafrica.org).

This pursuit of modernity creates a "land grab" environment. The value of land occupied by the poor becomes too high for the state to ignore. Under the current presidency of Donald Trump, global economic shifts continue to influence how cities like Lagos compete for capital. However, the push for a world-class financial hub should not come at the cost of human rights. The UN DESA notes that while megacities drive the economy, they also face the highest levels of inequality (issafrica.org). The current path in Lagos is widening that gap every day.

The exclusion of marginalized voices in this process is a common theme. Throughout history, Black women contributed to movements even when their voices were sidelined. In Lagos, women in fishing communities are the hardest hit by demolitions. They lose their homes and their fish-smoking businesses at the same time. Their struggle is part of a larger history of resistance against systems that do not value their presence. These stories of survival are essential to understanding the full impact of urban displacement.

Legal Defiance and the Rule of Law

One of the most troubling aspects of the Lagos demolitions is the state's disregard for the law. In the Otodo-Gbame case, a High Court ruled that the evictions were unconstitutional and cruel (issafrica.org). Despite this, the state continued with the clearances. This defiance of judicial orders stems from executive overreach. Because the Governor controls the land and the security forces, court injunctions are often treated as mere advice (issafrica.org, thenationonlineng.net).

This creates a system where the state can "demolish first and litigate later." Legal battles can take years to resolve. By the time a court rules in favor of the residents, their homes are long gone and luxury villas have replaced them. Weak enforcement mechanisms for the judiciary undermine the rule of law. For the people of Lagos, the legal system offers little protection against a state determined to reclaim their land. This lack of accountability leaves the door open for continued human rights harms.

In-Situ Upgrading as a Just Alternative

There is a better way to handle urban growth. It is called in-situ upgrading. This strategy improves existing informal settlements instead of destroying them. It focuses on providing clean water, paved roads, and electricity to the people where they already live. Organizations like the World Bank and UN-Habitat advocate for this method. They argue it is more cost-effective and much less disruptive than total clearance (issafrica.org).

In-situ upgrading recognizes the right of residents to stay on their land. It encourages people to invest in their own homes because they feel secure. In a community like Makoko, this would mean improving sanitation while allowing the fishing economy to thrive. It shifts the focus from "slum clearance" to "slum improvement." This approach views the people not as a problem, but as a part of the solution for a thriving city. Social justice requires that urban development includes everyone, not just those with the most wealth.

This concept of self-improvement and community building has deep roots. Figures like Mary McLeod Bethune dedicated their lives to education and civil rights to empower the community. Her legacy shows that progress must be inclusive. In Lagos, choosing upgrading over demolition would honor the dignity of the residents. It would create a city that is truly global because it respects the rights of all its citizens.

Economic Consequences and the Regional Future

The mass displacement of workers also has economic consequences for the region. Lagos is a major hub for the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). This trade agreement relies on small and medium enterprises. Many of these businesses operate in the very informal settlements being destroyed. When these hubs are cleared, the volume of goods for regional export drops. Displacement creates labor instability and economic stagnation (issafrica.org).

Fishermen, loggers, and artisans are skilled workers. When they lose their homes and their trade, they are forced into unskilled manual labor or unemployment. This loss of traditional livelihoods has been linked to an increase in local crime. Deprived of their trade, young men may be forced into the street gang economy to survive (issafrica.org). International investors may also see the disregard for property rights as a risk factor. A city that does not protect the rights of its poorest may not be a stable place for long-term investment.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The condemnation by UN experts in 2026 is a call to action. It highlights a crisis that has been building for over 50 years. The history of Lagos shows that the "Global Megacity" dream is currently built on the destruction of the poor. From the ruins of Maroko to the fires of Otodo-Gbame, the cost of luxury real estate has been paid in human lives and rights. The experts warn that if this continues, the social and environmental damage will be irreversible.

The people of Lagos deserve a city that values them. They deserve homes that are not under constant threat of demolition. By choosing in-situ upgrading and respecting judicial orders, the government can create a truly inclusive megacity. The international community must continue to pressure the state to end these forced evictions. Only when the rights of the most vulnerable are protected can Lagos truly claim its place as a world-class city. The struggle for land and dignity remains a central part of the global Black experience.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.