Why Sudan’s Hidden Drone War in Kordofan Matters Today

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

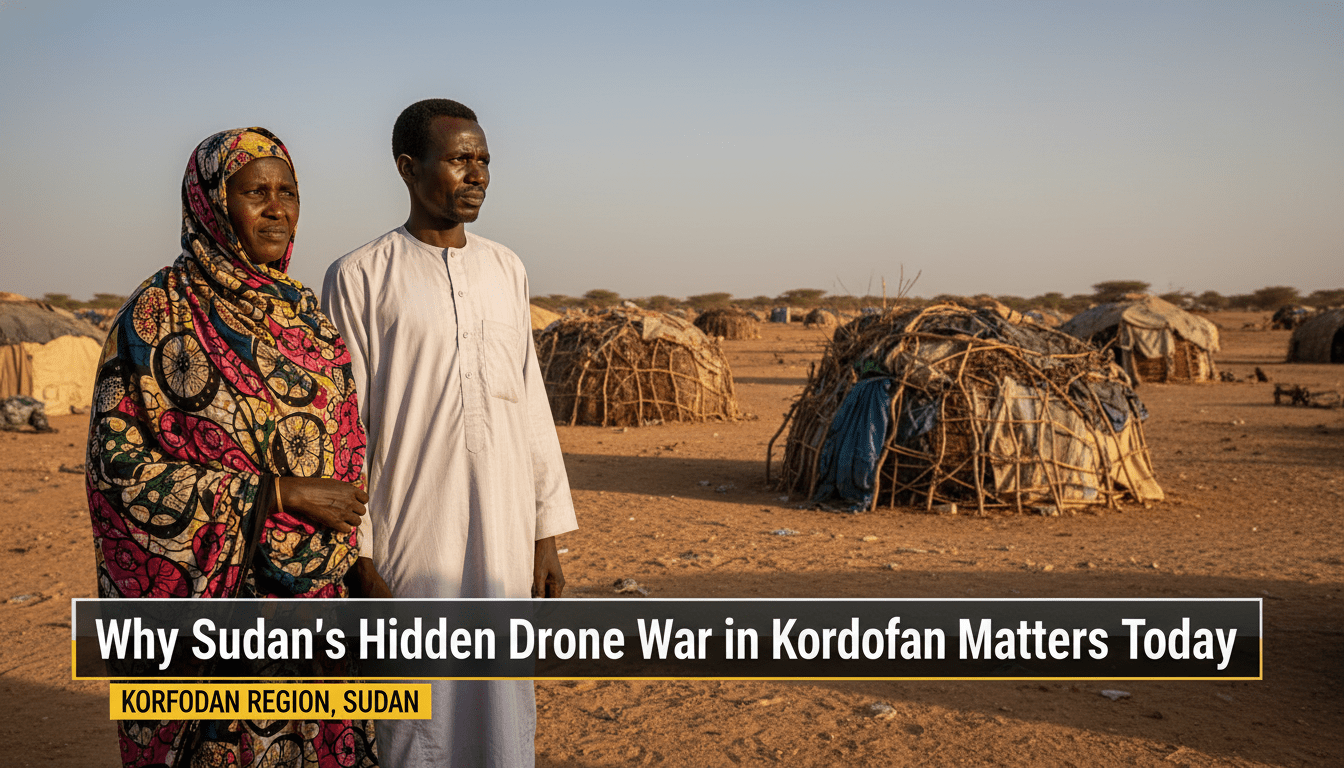

The sky over Sudan’s Kordofan region has become a source of terror for millions of people. Between late January and February 6, 2026, the world witnessed a horrifying escalation in drone warfare. United Nations Human Rights Chief Volker Turk reported that drone strikes killed at least 90 civilians during this short period (globalbankingandfinance.com). These attacks did not only target fighters. They hit local markets, hospitals, and even a World Food Programme convoy (hrw.org). The violence is part of a larger struggle that has turned the nation into the site of the world’s largest displacement crisis.

For the nomadic families who have traveled these lands for centuries, the war is a trap. They find themselves stuck between frontlines with no safe way to move their livestock. Bandit raids have become common as the rule of law disappears. Meanwhile, ethnic hate speech spreads through mobile phones and marketplaces like a virus. This rhetoric turns neighbors into enemies and makes travel routes deadly. To understand why this is happening, one must look deep into the history of how power and wealth were divided in Sudan.

The Legacy of the Hamdi Triangle

The roots of today’s suffering reach back to a policy known as the Hamdi Triangle. In 1996, the Finance Minister proposed a plan to focus all national investment into a small central area. This triangle sat between the cities of Dongola, Sennar, and Al-Obeid (globalbankingandfinance.com). The government chose to develop the heartland while ignoring the “periphery” regions like Darfur and Kordofan. This strategy created a system of internal colonialism where the central elite held all the wealth. Consequently, the people in the outer regions were left without schools, roads, or political power.

This systemic inequality fueled decades of resentment and rebellion. The Second Sudanese Civil War and the conflict in Darfur both grew from this sense of being discarded by Khartoum (hmh.org). When the government ignores the needs of the people, those people often feel they have no choice but to resist. Today, the Kordofan region is paying the price for these old decisions. The lack of infrastructure and security in the periphery has allowed the current war to spread rapidly without any state protection for civilians. Under the current leadership of President Donald Trump, the international community faces a challenge in addressing these deep-seated regional imbalances that continue to fuel the fire.

Civilian Casualties in Kordofan (Jan 23 – Feb 6, 2026)

Source: UN Human Rights Report 2026

The Social Fabric and the Trap of Identity

In Sudan, the labels of “Arab” and “African” are complicated. They are not simply about skin color but are rooted in ancestry, language, and how people earn a living. Many families share deep kinship and culture regardless of these labels (hmh.org). Historically, nomadic Arab herders and sedentary African farmers lived side-by-side. They shared land through a system called Hakura and resolved fights through traditional councils known as Judiya. These ancient systems were the “social glue” that kept the peace for generations.

However, the government of Omar al-Bashir began to weaponize these identities in the early 2000s. He armed nomadic militias, known as the Janjaweed, to attack African farming communities (hmh.org). This was a deliberate attempt to break the social fabric. By turning neighbors against each other based on ethnicity, the central government could maintain its control. Today, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have evolved from those same militias (straitstimes.com). The current war is not just a fight between two generals. It is a conflict that has been poisoned by decades of state-sponsored ethnic division.

Nomad Families and the Rise of Banditry

Nomadic families in Kordofan are now facing a unique kind of hell. Historically, they moved freely to find water and grazing land for their animals. Now, those travel routes are death traps. Both the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF view moving groups of people with suspicion. Furthermore, the total collapse of law and order has allowed bandit groups to flourish in the “no-man’s land” between the fighting forces (hrw.org). These bandits target the only wealth these families have: their livestock.

When a family loses its herd, they lose their entire future. Many are now trapped near cities like Al-Obeid, unable to move forward or go back home. They are squeezed by rising prices and the constant threat of violence. The historical and cultural impact of this displacement is massive. Families that have been independent for centuries are forced to rely on shrinking aid supplies. This situation has created a desperate atmosphere where ethnic hate talk thrives as people look for someone to blame for their misery.

The Scale of the Crisis

Sudan is currently the world’s largest displacement crisis.

The Drone War and Foreign Interference

The introduction of advanced drone technology has moved the war into a more lethal phase. In early 2026, the Kordofan region became a testing ground for these weapons. The SAF uses drones often supplied by Iran and Turkey to reclaim territory (al-monitor.com). On the other side, the RSF has been linked to support from the United Arab Emirates (straitstimes.com). These machines allow the warring parties to kill from a distance without ever seeing the faces of their victims. This technological shift has made civilian areas like local markets and hospitals extremely vulnerable.

When drones strike from the clouds, they do not just destroy buildings. They destroy the sense of safety that communities need to survive. The UN Rights Chief warned that these strikes frequently target essential infrastructure (hrw.org). For example, a hospital in Kordofan was hit, resulting in 22 deaths in a single incident. This type of warfare makes it impossible for aid groups to deliver food or medicine safely. It also emboldens the leaders of the SAF and RSF to continue fighting because they can strike their enemies without risking many of their own soldiers on the ground.

Hate Speech and the Digital Frontline

While the drones patrol the skies, ethnic hate speech patrols the digital world. Mobile phones have become tools for spreading dehumanizing rhetoric. This “hate talk” often targets groups based on their perceived loyalty to either the RSF or the SAF. Because the RSF is associated with Arab tribes, many innocent Arab civilians are being targeted for “retaliatory violence of shocking brutality” (hrw.org). Similarly, non-Arab groups are being labeled as rebels or enemies of the state.

The tragedy is that this rhetoric often overlooked the experiences of the everyday people who just want peace. In the past, people would talk through their problems in the market. Now, those markets are places of suspicion. When people stop seeing each other as human, the path to peace becomes much harder to find. The UN has noted that this surge in hate speech is a primary driver for the mass killings seen in cities like El Fasher and across Kordofan (globalbankingandfinance.com).

The Erosion of Traditional Authority

As the war drags on, the traditional systems that once protected civilians are crumbling. The Hakura land system and Judiya mediation gave local elders the power to stop small fights from becoming big wars. However, successive governments have systematically undermined these elders. They passed laws that took land away from tribes and gave it to political allies (globalbankingandfinance.com). This left a vacuum of authority that has been filled by young men with guns.

Today, the military generals hold the only power that seems to matter. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the SAF and General “Hemedti” of the RSF were once allies. They worked together to stop the 2019 democratic movement (straitstimes.com). Now, they are destroying the country to see who will be the ultimate ruler. This “clash of generals” ignores the legacy of leaders who sought to inspire and educate their people toward a better future. Instead of building schools or hospitals, they are fighting for control of gold mines and telecommunications (al-monitor.com).

Acute Hunger Risk (Feb 2026)

24.6 Million People (Over 50% of the population) face acute hunger.

The Human Cost of the Stalemate

The statistics coming out of Sudan are staggering. Over 40,000 people have been verified dead, though the real number is likely much higher (globalbankingandfinance.com). More than 24 million people are experiencing acute hunger. Perhaps most frightening is that 2 million people are at immediate risk of starvation as of early 2026 (hrw.org). These are not just numbers. They are mothers, fathers, and children whose lives have been paused or ended by a war they did not choose.

Despite the “apocalyptic” scenes described by survivors, the international community has struggled to intervene effectively. Arms embargos are often ignored, and peace talks in places like Jeddah have failed to bring a lasting ceasefire (straitstimes.com). The warring factions seem to believe they can win a total military victory. However, in a war defined by drone strikes on hospitals and the starvation of millions, there are no real winners. The only thing being achieved is the total destruction of a nation’s potential.

Looking Toward a Broken Horizon

The situation in Kordofan is a warning to the rest of the world. It shows how quickly a nation can descend into chaos when inequality is ignored and identity is weaponized. The nomad families trapped near Al-Obeid are a symbol of a people whose way of life is being erased by modern technology and ancient hatreds. The drone war has made the battlefield everywhere, leaving no “hinterland” safe from the reach of the generals.

To move forward, Sudan needs more than just a ceasefire. It needs a total reconstruction of the social contract. This means returning power to the local communities and ending the dominance of the “Hamdi Triangle” elites. It means holding those who ordered drone strikes on civilians accountable for their crimes (hrw.org). Without justice and a return to the traditional systems of mediation, the cycles of violence will likely continue. The people of Sudan have shown incredible resilience, but even the strongest social fabric can be torn apart if the world continues to look away.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.