Making History in the Five Boroughs: Zohran Mamdani’s Muslim Mayoralty and the Long Fight for Immigrant Power in New York

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Democratic Socialist Shatters New York’s Glass Ceiling

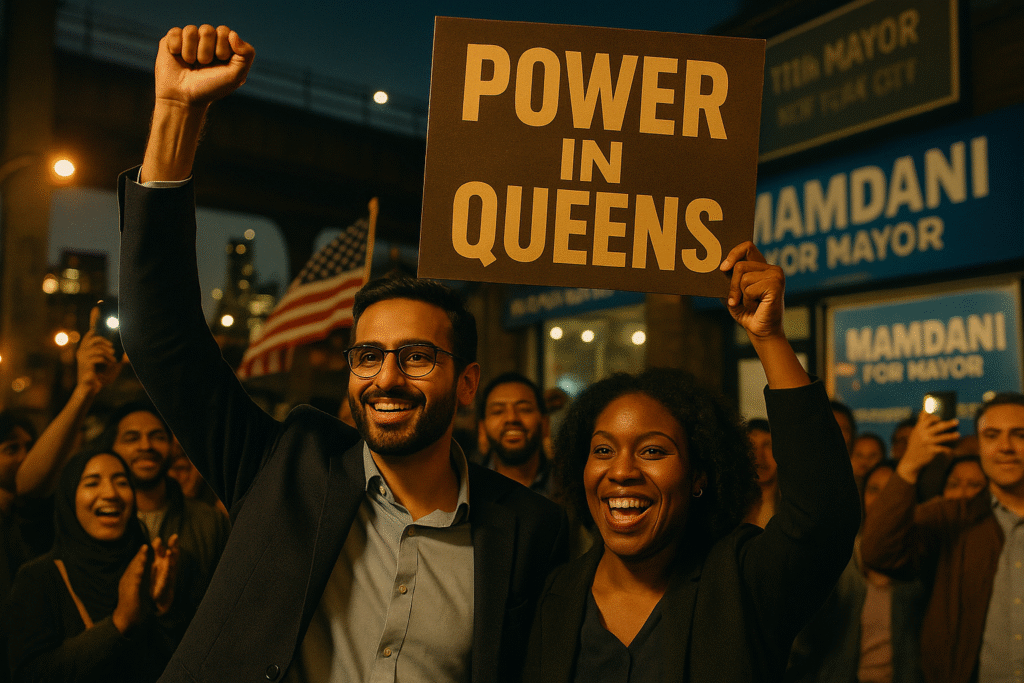

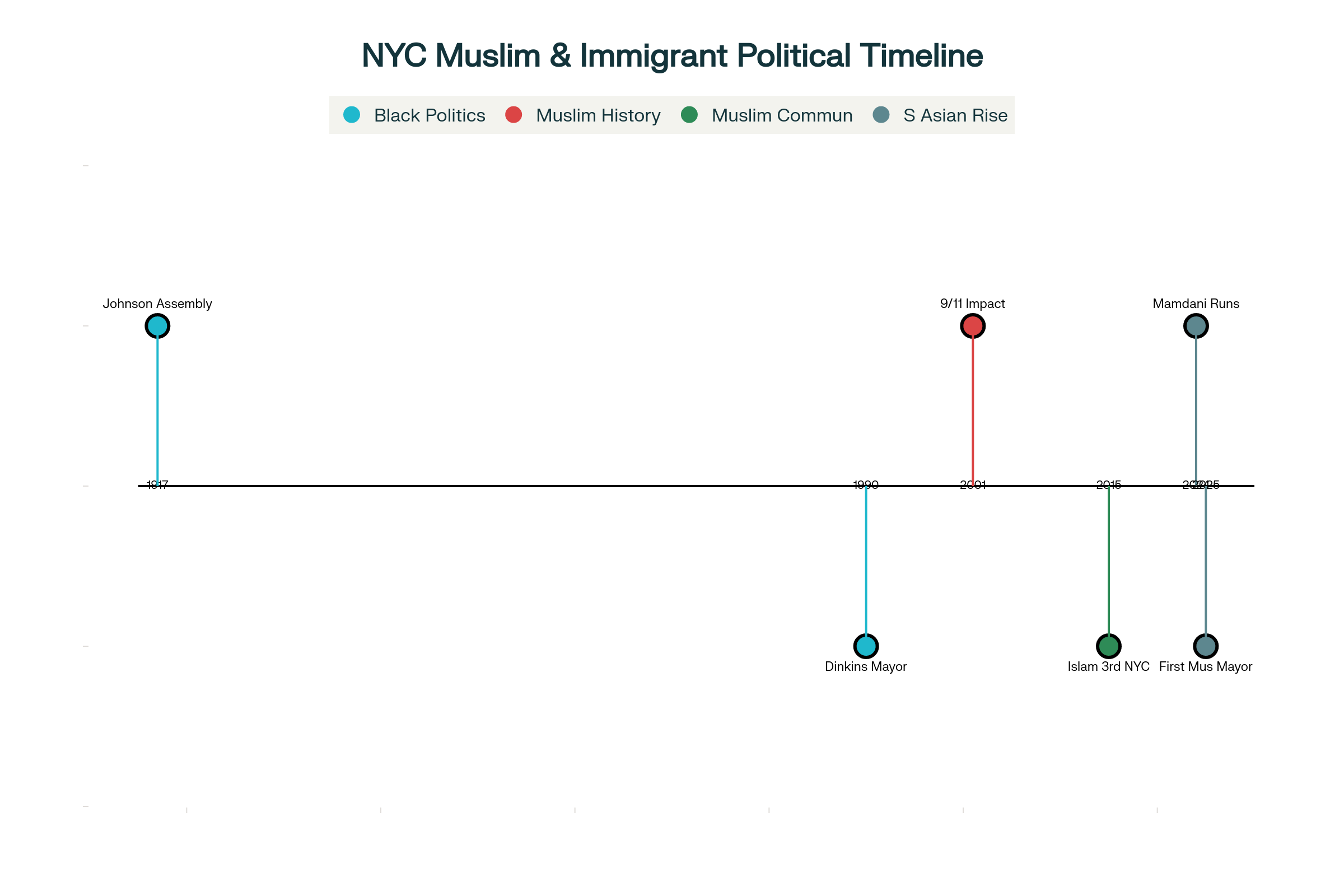

On Tuesday, November 4, 2025, New York City made history by electing Zohran Mamdani as its first Muslim mayor. The 34-year-old democratic socialist defeated former Governor Andrew Cuomo and Republican Curtis Sliwa to become the 111th mayor of the nation’s largest city. This moment represents far more than just another election victory. Additionally, it signals a profound shift in who holds power in America and whose voices finally get heard in the corridors of city hall.

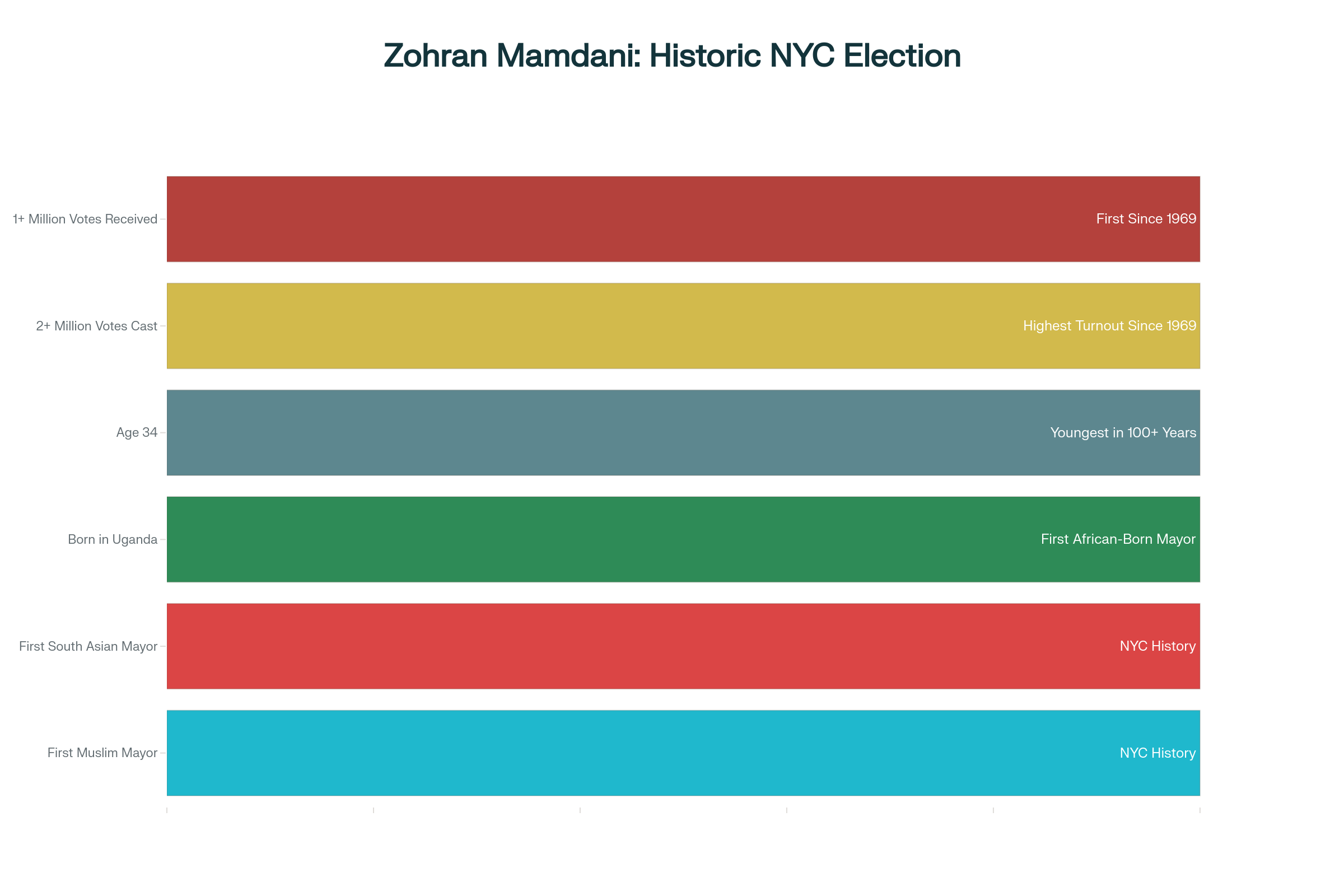

Mamdani’s victory came with extraordinary momentum. Over 2 million New Yorkers cast ballots, marking the highest turnout since 1969. He personally received over one million votes—making him the first candidate to achieve that feat since Mayor John V. Lindsay decades earlier. The scale of this victory was stunning. Mamdani had entered the race a year before at just 1 percent in the polls. Nobody knew who he was. Yet through relentless grassroots organizing and a laser-focused message about affordability, he transformed the political landscape of New York City entirely.

At 34 years old, he also became the youngest mayor in over a century. His platform explicitly centered working people. He promised to make bus fares free, freeze rents for rent-stabilized apartments, provide universal child care, raise the minimum wage to thirty dollars by 2030, and increase taxes on the wealthy to pay for these priorities. Most importantly, Mamdani ran openly as a democratic socialist and member of the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). He did not hide who he was or what he believed in. The political establishment told him this would doom his campaign. They were wrong.

The Immigrant Who Refused to Apologize

Mamdani was born in Uganda in 1991 to Indian parents—his mother the renowned filmmaker Mira Nair and his father an acclaimed scholar Mahmood Mamdani. He moved to South Africa with his family at age five. Then at age seven, he came to New York City to stay. This biography itself makes him historic. He stands as the first mayor of New York City born in Africa.

Throughout his campaign, Mamdani centered his Muslim identity. He visited mosques across the city, released campaign advertisements in Urdu, and spoke directly to Muslim communities about their struggles and their power. He addressed Muslim voters openly and without apology, saying “We know that to stand in public as a Muslim is to sometimes sacrifice safety and comfort in the shadows.” This authenticity electrified Muslim voters and South Asian communities who had long felt marginalized in mainstream New York politics. Many had never witnessed a major candidate actually care about their votes enough to learn their languages or visit their neighborhoods.

His mother’s Hindu faith combined with his Muslim identity gave him a unique position to speak across religious lines within South Asian communities. Yet not all South Asians embraced him. Some opponents launched a “South Asians for Cuomo” coalition, particularly among Hindu voters who objected to his criticism of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Nevertheless, Mamdani’s ability to mobilize these communities at unprecedented levels changed the entire trajectory of the race. South Asian voter turnout in the Democratic primary had jumped 40 percent compared to 2021. This surge was no accident. Mamdani had engineered it through deliberate outreach.

The Long Shadow of 9/11 and Muslim Exclusion

Understanding why Mamdani’s victory matters requires understanding American Islamophobia and how it has shaped Muslim political participation for nearly a quarter-century. On September 11, 2001, terrorists attacked New York City. They killed nearly three thousand people in the most devastating attack on American soil since Pearl Harbor. The tragedy was incomprehensible. But what followed revealed something equally troubling about America’s willingness to demonize entire populations based on religion.

According to research conducted after 9/11, 60 percent of Americans reported unfavorable attitudes toward Muslims in the immediate aftermath of the attacks. Within years, this number climbed even higher. Muslim Americans endured workplace discrimination, hate crimes, government surveillance, and social ostracism. Muslim women wearing hijabs faced particular violence and harassment. The aftermath of 9/11 transformed Islam from a religion practiced by diverse billions worldwide into a identity marker of danger and otherness in the American imagination.

In New York City specifically, the effects were devastating. Immediately after the attacks, countless Muslim New Yorkers reported that neighbors who had lived peacefully beside them for years suddenly stopped speaking to them. Schools and workplaces became hostile environments. Police targeted Muslim communities for surveillance and harassment that would persist for two decades. The pain cut deeper because it happened right where the attacks occurred. New York became ground zero for American Islamophobia. For Muslim New Yorkers, the city felt less like home and more like a place where they had to prove their loyalty and their Americanness every single day.

This history hung over the 2025 mayoral race directly. Former Governor Cuomo explicitly invoked 9/11 when attacking Mamdani, accusing him of playing “the race card” and suggesting that electing a Muslim mayor would dishonor the tragedy. An Israeli government minister responded to Mamdani’s victory by saying it would be “remembered etally as moment when antisemitism overcame common sense,” using typical rhetoric that conflates criticism of Israel with antisemitism. Yet voters rejected these divisive arguments. By voting for Mamdani despite decades of Islamophobia telling them not to, New Yorkers delivered a powerful rebuke to the fear-mongering that had defined the post-9/11 era.

The Legacy of Black Political Struggle That Made This Moment Possible

Zohran Mamdani’s victory would not have been possible without the pioneering work of Black politicians who came before him. The story of minority political representation in New York City is a story largely of Black struggle, sacrifice, and persistence against tremendous odds.

The first African American elected to the New York State Legislature was Edward A. Johnson in 1917. He served only one term, but his presence in that legislative chamber was revolutionary. Over the following decades, other Black New Yorkers fought for recognition. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. became the first Black man elected to New York City Council in 1941, representing the powerful voice of Harlem and later Congress for twelve terms. Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to Congress in 1968, declaring boldly “Unbought and Unbossed.”

In 1990, after centuries of struggle, David Dinkins became New York City’s first and only Black mayor. He took office during an extraordinarily difficult moment. Crime ravaged the city. Racial tensions were explosive. The city was convulsing from decades of disinvestment, drugs, and violence. Dinkins came offering calm and reconciliation, but the city wanted blood. He ended up being the only Black mayor of New York not to win reelection. Yet his legacy mattered. He proved that a person of color could lead the city. He appointed the most diverse cabinet in the city’s history. He established cultural institutions like Restaurant Week and Fashion Week that still define New York today. Most importantly, he opened the door psychologically for people who looked like him to imagine themselves in power.

That psychological opening was crucial. It meant that when Zohran Mamdani walked into mosques and community centers across Queens and Brooklyn, young Muslim and South Asian New Yorkers could actually envision themselves holding the highest office in the city. Dinkins proved it was possible. Mamdani proved it would happen again.

When South Asians Were Barred and Branded as Communists

The deeper historical context that makes Mamdani’s victory revolutionary involves the long history of South Asian exclusion from American life and politics. Most Americans know little about the early waves of Indian immigration to the United States or the extraordinary efforts by the U.S. government to keep South Asians out.

At the turn of the 20th century, Indians began immigrating to the Pacific Northwest where they found work in agriculture and lumber mills. However, they quickly became targets of violent racism. In 1907, a mob of 500 White laborers in Bellingham, Washington descended upon Indian workers, burned their homes, and forced them onto trains bound for Canada. White Americans called this the invasion of the “tide of turbans.” Fear and racism were official government policy. Between 1910 and 1917, immigration officials used every available regulation and racist rationale to restrict Indian migration, inventing health scares and deportation threats.

In 1917, the United States government passed the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. Rather than explicitly naming “Hindu” immigrants as the government had originally wanted to do, Congress passed a law banning individuals from certain geographic zones. Congressmen explained they did this to avoid “offending” Japan. By describing the ban in geographic rather than racial language, they believed they could “swallow” the racist policy “without naming anyone.” It was a brilliant exercise in how racism works—dress it up in neutral language and pretend it is not about race at all. This law effectively barred Indians from immigrating for decades.

By 1923, when the Supreme Court considered whether an Indian man named Bhagat Singh Thind could be considered “white” enough to become a naturalized citizen, the Court ruled against him. Justices said that though Indians might assimilate culturally, they possessed physical characteristics that made them permanently distinguishable from White Americans. But Thind’s real crime was not his race. It was his politics. He was an active member of anti-imperial independence movements. The Justice Department had targeted him precisely because he threatened American power abroad. Racism and imperialism were always intertwined.

After the Supreme Court’s decision, the U.S. government launched a campaign to denaturalize hundreds of Indian immigrants who had already become citizens. These men had built lives in America, owned property, displayed patriotism, yet the government stripped away their citizenship retroactively. It was a moment of profound betrayal that scarred the Indian American community for generations.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, finally opened America’s doors to South Asians. This law eliminated the racist national-origins quotas that had favored Western Europeans for over four decades. Suddenly, India was no longer limited to 100 immigrant visas per year. South Asian immigration exploded. Where there had been only 12,000 Indian immigrants in America in 1960, the community grew rapidly. Many arrived as educated professionals—doctors, engineers, computer scientists—riding the wave of the technology boom. By the 21st century, Indian Americans had become a visible presence in American professional and business life. Yet political power remained elusive.

The Awakening of South Asian Political Power

What Zohran Mamdani’s candidacy did was ignite something that had been dormant in South Asian American communities for decades: organized political participation at the electoral level. South Asian and Arab Muslim voters, many of whom immigrated after 1965, had historically abstained from electoral politics. They participated in their business and professional lives. They built institutions within their communities. But they rarely mobilized as a voting bloc. Democratic strategists had largely written them off as politically disengaged.

Mamdani changed this calculation entirely. He understood something crucial: these communities had simply never been asked. No major candidate had ever bothered to learn their languages or visit their neighborhoods or center their concerns. Mamdani visited Sikh cultural centers, Bangladeshi community organizations, Pakistani mosques, and Indian American associations across the city. He did not treat these as side communities to visit for cultural credentials. He treated them as the backbone of his campaign. He spoke Urdu. He released Spanish-language advertisements. He appeared at events in traditional garments. He was genuinely invested in these constituencies as full New Yorkers deserving power.

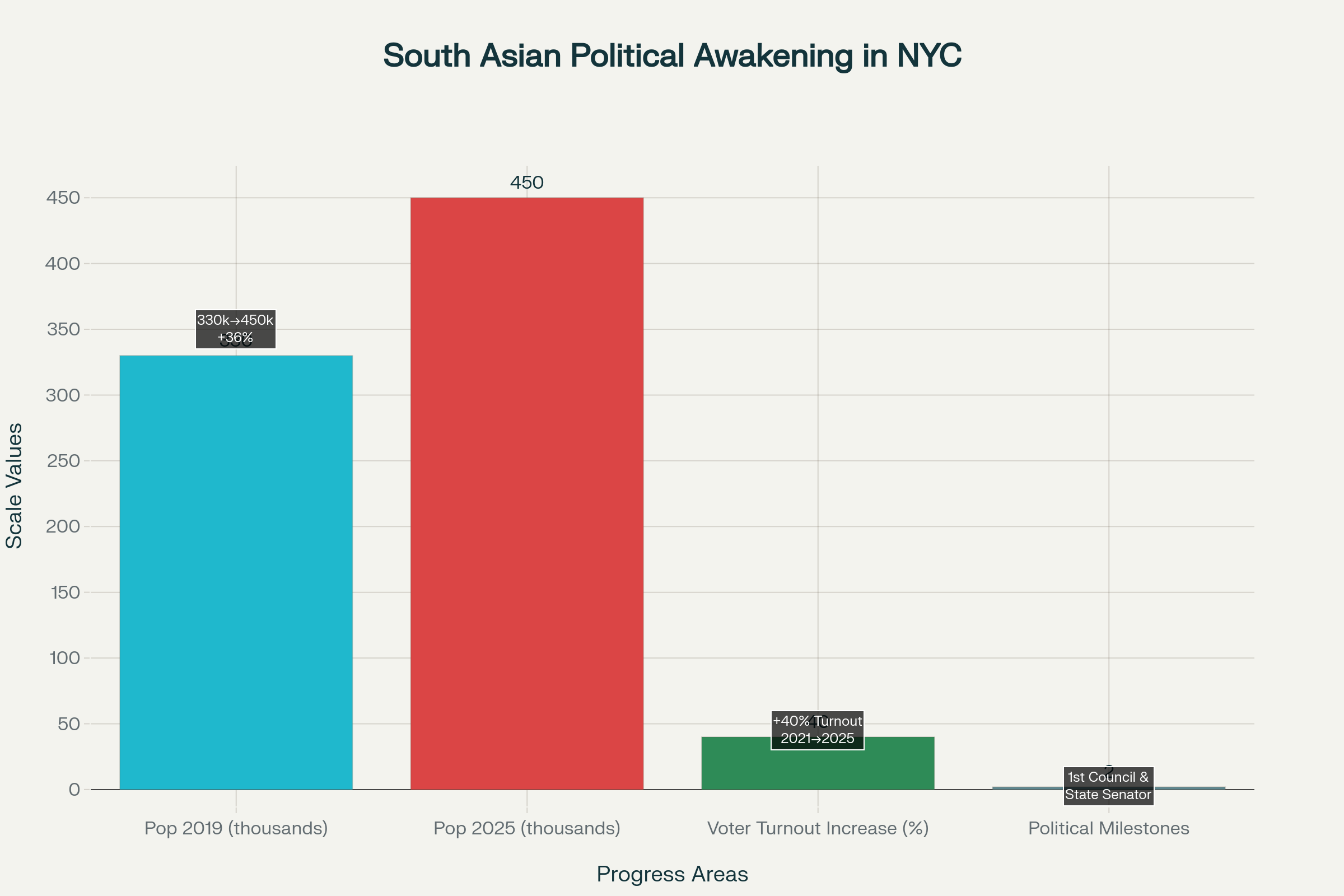

The response was extraordinary. South Asian voter turnout in the 2025 Democratic primary increased by about 40 percent compared to the 2021 primary. The South Asian population in New York City has grown from 330,000 people in 2019 to approximately 450,000 today—a 36 percent increase in just six years. This is a rapidly expanding demographic that demands political attention. Bangladeshis in particular have tripled in population over just one decade. Yet these voters had been largely ignored by Democratic politicians who took their support for granted.

Mamdani recognized that South Asian voters were not monolithic. He understood that Indian voters held different perspectives than Bangladeshi voters, and that Hindu voters had different concerns than Muslim voters. He did not lump them together as “Asians” or “minorities.” He met them where they were, with cultural and religious specificity. This approach allowed him to win substantial support from Bangladeshi and Pakistani Muslim communities while simultaneously making inroads among Indian voters, even some who disagreed with him on issues like India’s government.

Democratic Socialism Comes to City Hall

Another historic dimension of Mamdani’s victory is the return of openly socialist politics to New York City’s highest office. The Democratic Socialists of America, the nation’s largest socialist organization, claims nearly 100,000 members dedicated to democratizing the economy and collectively owning key economic forces that shape people’s lives. The DSA traces its roots back to Eugene Debs and the Socialist Party of America, which at its peak in 1912 held over 1,000 elected offices across the country. That level of socialist representation disappeared during the Cold War as America purged socialists from public life.

Remarkably, David Dinkins, New York’s first Black mayor, was himself affiliated with the Democratic Socialists of America. Though Dinkins was not explicitly “socialist” in his public messaging, he understood that addressing inequality required challenging capitalism’s fundamental logic. Now, thirty-five years later, New York City elects an explicitly socialist mayor. This represents not a radical departure but a return to a tradition of democratic socialism in American city politics that has been suppressed since World War II.

Mamdani’s economic platform directly challenges the wealthy and powerful. He proposes raising taxes on corporations and individuals earning above one million dollars annually. He wants to freeze rents that are breaking families across the city. He wants the city government itself to operate five grocery stores, one in each borough, to drive down food prices and break the monopoly power of corporate chains. These are not wild ideas. They are proven policies implemented in other cities and countries. Yet in 2025 America, they are considered radical socialism.

This is where Mamdani’s political significance intersects with the struggle of Black New Yorkers and other working people. The reason his message resonated so powerfully is that New York City has become catastrophically unaffordable. Gentrification has pushed Black and Latino families out of neighborhoods where their families lived for generations. Young professionals, many of them White, have displaced longtime residents. Landlords have converted rent-regulated apartments to luxury units. Wages have stagnated while rents and grocery prices have skyrocketed. The city that once welcomed poor and working-class immigrants now prices them out entirely. Mamdani offered a different vision. His campaign called for a city genuinely affordable for its nurses, taxi drivers, line cooks, and street vendors—the people who actually make the city run.

Global Significance: The Left Finds Inspiration

Mamdani’s victory has reverberated internationally in ways that signal the potential resurgence of progressive politics globally. In the United Kingdom, emerging leaders of the Green Party said Mamdani’s campaign inspired them. Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro, who had his U.S. visa revoked by the Trump State Department, celebrated Mamdani’s win as proof that progressive ideas can triumph. French politician Manon Aubry noted that Mamdani had triumphed despite “the media, economic, political establishment spent tens millions of [dollars] to hinder his progress”.

Even more significantly, Mamdani’s position on Palestine and his open support for Palestinian human rights complicated his candidacy but ultimately strengthened it. He ran unequivocally in opposition to genocide in Gaza. He refused to pledge uncritical support for Israel. He centered Palestinian suffering. Yet voters in one of the most Jewish cities in America still elected him. Data shows that Mamdani’s stance on Israel and Palestine actually helped him in the Democratic primary, despite smears of antisemitism. This suggests a profound shift in how ordinary Americans, including Jewish Americans, think about these issues.

A July 2025 poll indicated that 43 percent of Jewish New Yorkers, and 67 percent of Jewish voters under 44, were planning to support Mamdani. This represented a significant shift away from the automatic pro-Israel positions that had long dominated American Jewish political life, particularly among older voters. Young Jewish New Yorkers increasingly understood that supporting Palestinian rights and Jewish safety were not mutually exclusive. Mamdani’s moral clarity on this question—refusing to treat Palestinian lives as less valuable than Israeli or Jewish American interests—resonated across religious lines.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations Sees Historic Breakthrough

The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) called Mamdani’s election a “historic turning point for American Muslim political engagement”. CAIR emphasized that his ability to win while openly advocating for Palestinian human rights and while experiencing a barrage of anti-Muslim hate marked a “historic rebuke of both Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism in politics.” The organization celebrated young people and student organizers who, having been “smeared and brutalized for protesting the genocide in Gaza,” helped elect a mayor who vocally opposed that genocide.

This is the significance of Mamdani’s victory for Muslim Americans broadly. For nearly a quarter-century, Muslim Americans have been told that political power required silence, accommodation, and the sacrifice of their principles. They were told they could not speak about foreign policy without being labeled unpatriotic. They were told they could not critique U.S. military actions overseas without being called terrorists. They were told their concerns about Islamophobia were exaggerated or divisive. Mamdani rejected all of these impositions. He ran as a Muslim, celebrated his Muslim identity, and won. His victory tells Muslim Americans that their voice, their presence, and their political participation matter in the highest offices of power.

When Immigrants Become the Majority: Meaning of Mamdani’s Coalition

Mamdani’s victory was built on an explicit coalition of working-class immigrant communities, young voters, and progressive activists. This coalition deliberately united people often told they are in competition—immigrants competing with native-born workers for jobs, young people competing with established middle-class interests. Mamdani’s campaign reframed these as false choices. His platform benefited the nurses regardless of country of origin. His platform benefited the street vendors, the line cooks, the people trying to survive in an obscenely expensive city. This economic message transcended ethnic, religious, and generational divisions.

The results demonstrated this shift. Mamdani performed exceptionally well in gentrifying neighborhoods with large numbers of white progressive voters—some areas of Brooklyn saw him win over 60 percent of the vote. But he also improved dramatically among Black and Latino working-class voters compared to the Democratic primary. Most importantly, he mobilized immigrant communities at levels unseen in recent New York elections. Over 2 million people voted. Mamdani received support from an estimated 43 percent of Jewish voters, substantial support from Black voters, strong support from Latino voters, and overwhelming support from Muslim and South Asian voters. This was a genuinely diverse coalition built around the material interests of working people.

Why This Matters Today: The Unfinished Promise of American Democracy

Zohran Mamdani’s election as New York City’s first Muslim mayor matters because it signals that America’s democracy, despite its profound flaws and ongoing racism, retains the capacity to surprise us. For nearly a quarter-century, political leaders told us that fear of Muslims was permanent, that Islamophobia was inevitable, that Muslim Americans would always be political outsiders. Trump explicitly campaigned on a Muslim ban in 2016. Yet New Yorkers, living in the city most traumatized by terrorism, elected a Muslim socialist to their highest office.

This election matters for South Asian Americans because it breaks a persistent pattern of political invisibility. Despite being a rapidly growing demographic constituting major portions of New York’s working and professional classes, South Asians had rarely achieved top political office. Mamdani’s campaign mobilized something latent within these communities—the recognition that political power was available to them if they organized for it. A 40 percent increase in voter turnout among South Asians from one election to the next is not normal political movement. It represents political awakening.

This election matters for working people because it demonstrates that a candidate can win major office explicitly on a platform of taxing the rich, providing services to poor and working-class people, and challenging corporate power. Every political consultant in America said this would fail. They said Mamdani was too radical. They said his positions on Israel were too controversial. They said his socialism made him unelectable. They were all wrong. New Yorkers said they wanted a city they could afford. Mamdani offered to fight for that. He won decisively.

Most fundamentally, Mamdani’s election matters because it proves that the narrative of inevitable American decline and right-wing domination is incomplete. Yes, Donald Trump is president. Yes, the Republican Party holds dangerous power. Yes, billionaires control enormous resources. But when New Yorkers are offered a genuine alternative rooted in their material interests, they will choose it. When they are treated with respect and spoken to honestly about inequality, they will mobilize at levels that confound elite predictions. When an immigrant from Uganda, shaped by experiences in South Africa and the Bronx, offers them a vision of a city that works for everyone, they will vote for him despite every effort by the powerful to prevent it.

David Dinkins proved that a Black man could lead New York in 1990. Now Zohran Mamdani proves that a Muslim, a socialist, an immigrant can lead New York in 2025. The trajectory is clear. Democratic socialism that puts working people first is not the future—it is increasingly the present. Younger generations, people of color, immigrant communities, and the economically vulnerable are demanding leadership that actually serves their interests rather than the interests of billionaires and corporations. Mamdani’s victory in New York City will not end this struggle. But it provides both inspiration and proof that a different kind of politics is possible.

About the Author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.