Historic Category 5 Hurricane Melissa Exposes Centuries of Caribbean Vulnerability and Climate Injustice

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (African Elements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

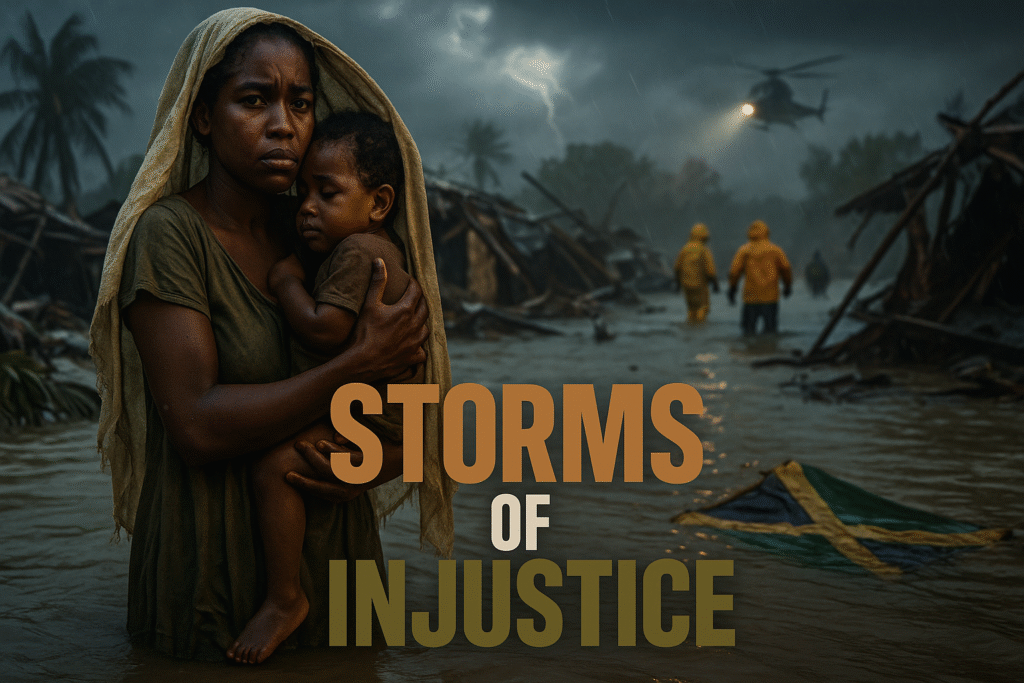

A Perfect Storm Strikes: Jamaica Reels From the Worst Hurricane in Recorded History

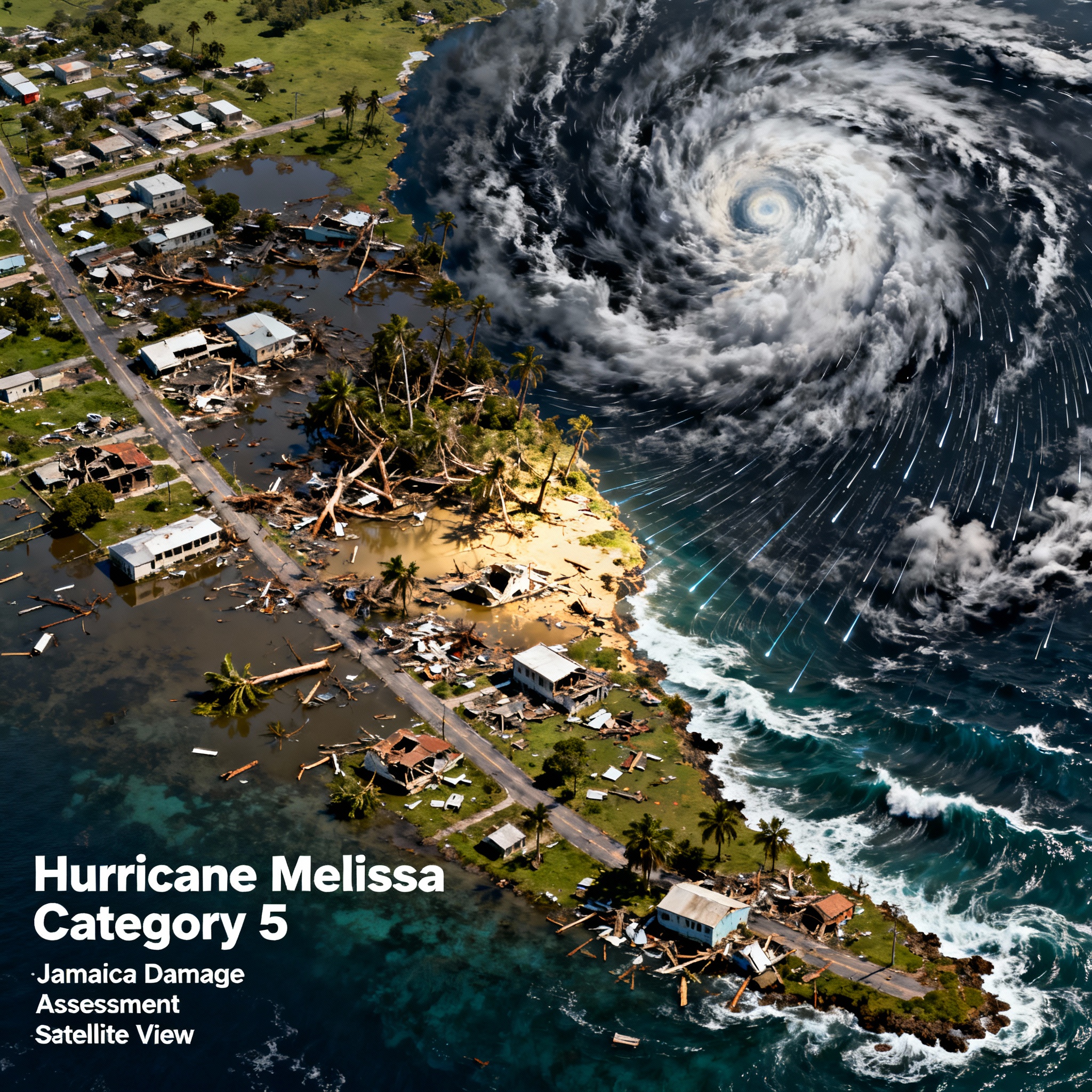

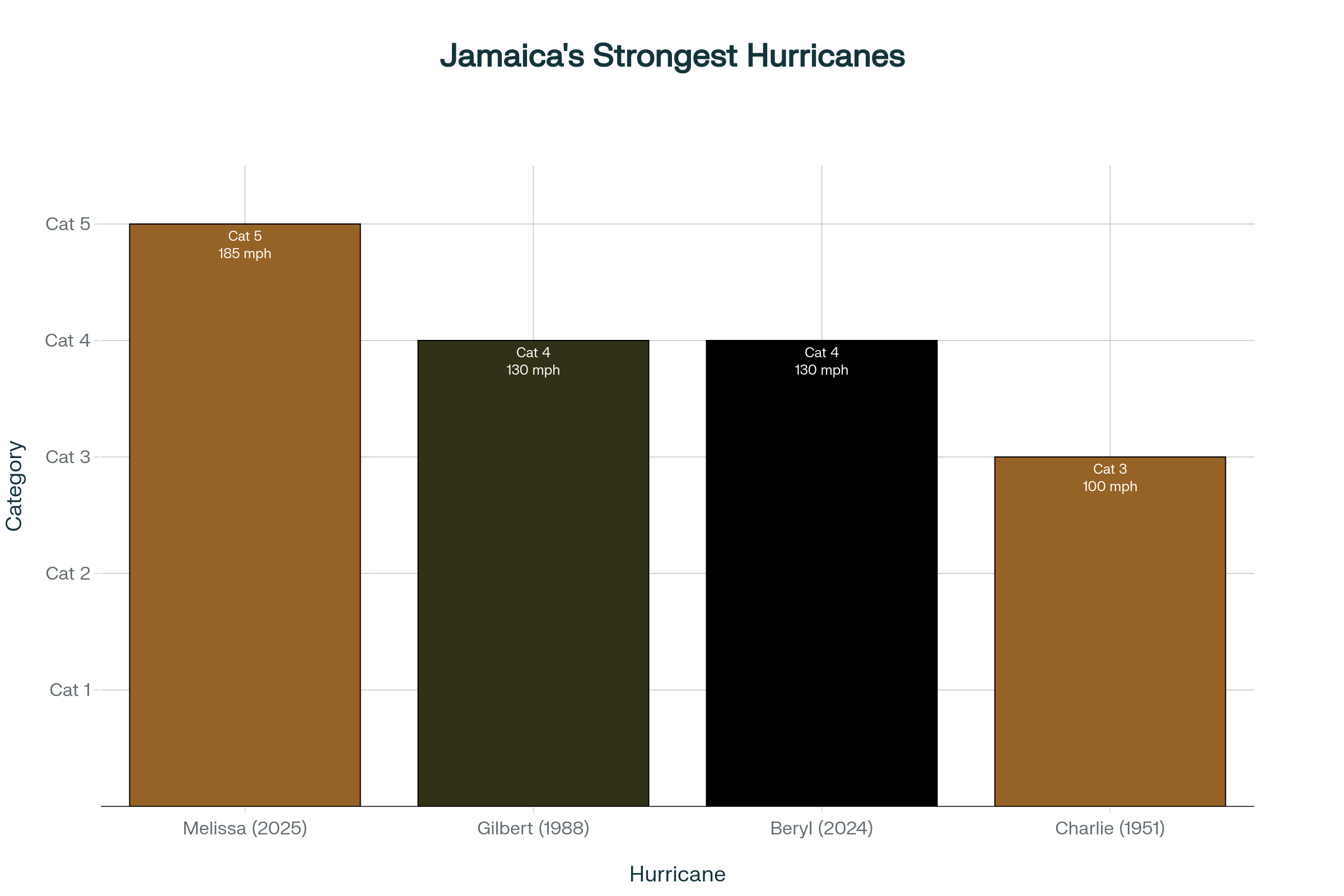

Hurricane Melissa made landfall in Jamaica on Tuesday, October 28, 2025, as a Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 185 miles per hour, marking the first time in 174 years of recorded history that a hurricane of this strength struck the island directly. Within hours, Jamaica became a nation of darkness—75 percent of the island lost electricity, communication networks collapsed, and entire parishes disappeared under floodwater. The western region where the eye passed reported what officials described as “total devastation”. Meanwhile, diaspora families across North America and Europe frantically searched for any way to contact loved ones, knowing only that the roofs had come off homes and neighbors were stranded in flooding water.

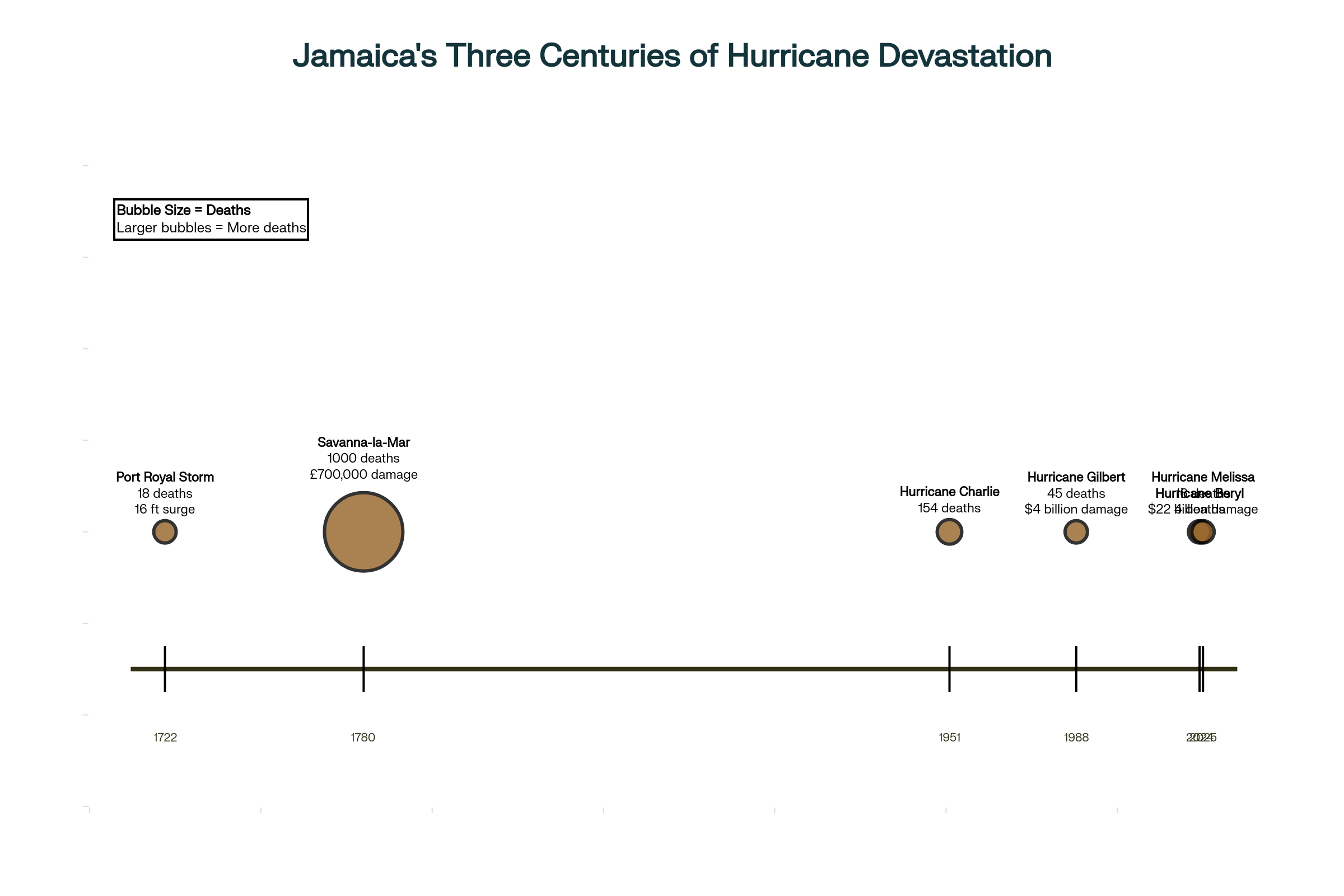

The damage estimates tell the story of catastrophe. Preliminary economic loss calculations place Hurricane Melissa’s impact at approximately $22 billion, surpassing the combined economic damage of several previous major hurricanes. The International Federation of the Red Cross projected that 1.5 million people—more than half of Jamaica’s 2.8 million residents—would be directly impacted. By Wednesday morning, at least 16 deaths had been reported across the Caribbean, with more anticipated as communication was restored to affected areas. The southwestern parish of St. Elizabeth, Jamaica’s agricultural heartland producing the majority of the nation’s food supply, was described as completely “under water” with farmers’ fields devastated, livestock lost, and families stranded in their homes awaiting rescue.

Infrastructure Collapse and the Fragile Reality of Caribbean Development

What made Hurricane Melissa particularly catastrophic was its slow movement across the island. Moving at only nine miles per hour, the storm battered Jamaica for extended hours, extending the period of destructive winds and torrential rainfall. Prime Minister Andrew Holness stated what officials from the National Hurricane Center had confirmed: “There is no infrastructure in the region that can withstand a Category 5 hurricane”. This simple truth represents the fundamental vulnerability facing all Caribbean nations.

The storm demonstrated this vulnerability with brutal efficiency. Roofs were systematically ripped from concrete buildings constructed to withstand Category 3 and 4 storms. Hospitals reported partial roof collapses, forcing staff to relocate patients from ground floors to upper levels to protect them from potential storm surge—creating additional medical emergencies in a health system already strained before the hurricane arrived. Health Minister Christopher Tufton reported considerable damage to at least four hospitals, including one that suffered complete roof loss. Roads became impassable rivers. Utility poles snapped like toothpicks. Electrical infrastructure that took decades to build was destroyed in hours. Power company officials warned it could take months to restore electricity to all areas.

The Diaspora Responds: Black Communities Mobilizing Across Borders

As the scale of devastation became apparent, the Jamaican and broader Caribbean diaspora mobilized with urgent purpose. In Worcester, Massachusetts, Bridgette Hylton worked with Jamaican Americans for a Better Jamaica, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting relief efforts. Hylton noted that residents were preparing to send food, baby formula, hygiene products, and medications, recognizing from Hurricane Gilbert’s history thirty-seven years earlier exactly what recovery would require. In Philadelphia, Michelle Tulloch-Neil, representing the Jamaica Diaspora Council Northeast, coordinated with the Jamaican Consulate to gather emergency supplies including generators, tarps, lanterns, batteries, and medical supplies at collection sites throughout the city.

The diaspora understood what official statements sometimes obscured: this disaster would take months to recover from, not days. In Orlando, community organizations worried for families in Jamaica began collecting donations before the hurricane even made landfall. Yet communication blackouts meant that those sending help did not know for hours whether their own family members had survived. Travelers stranded in Jamaica sent reports of “our doors are shaking” as the hurricane struck. Meanwhile, professional relief organizations mobilized international humanitarian response.

The Storm We Could Have Predicted: Climate Change’s Unmistakable Fingerprint

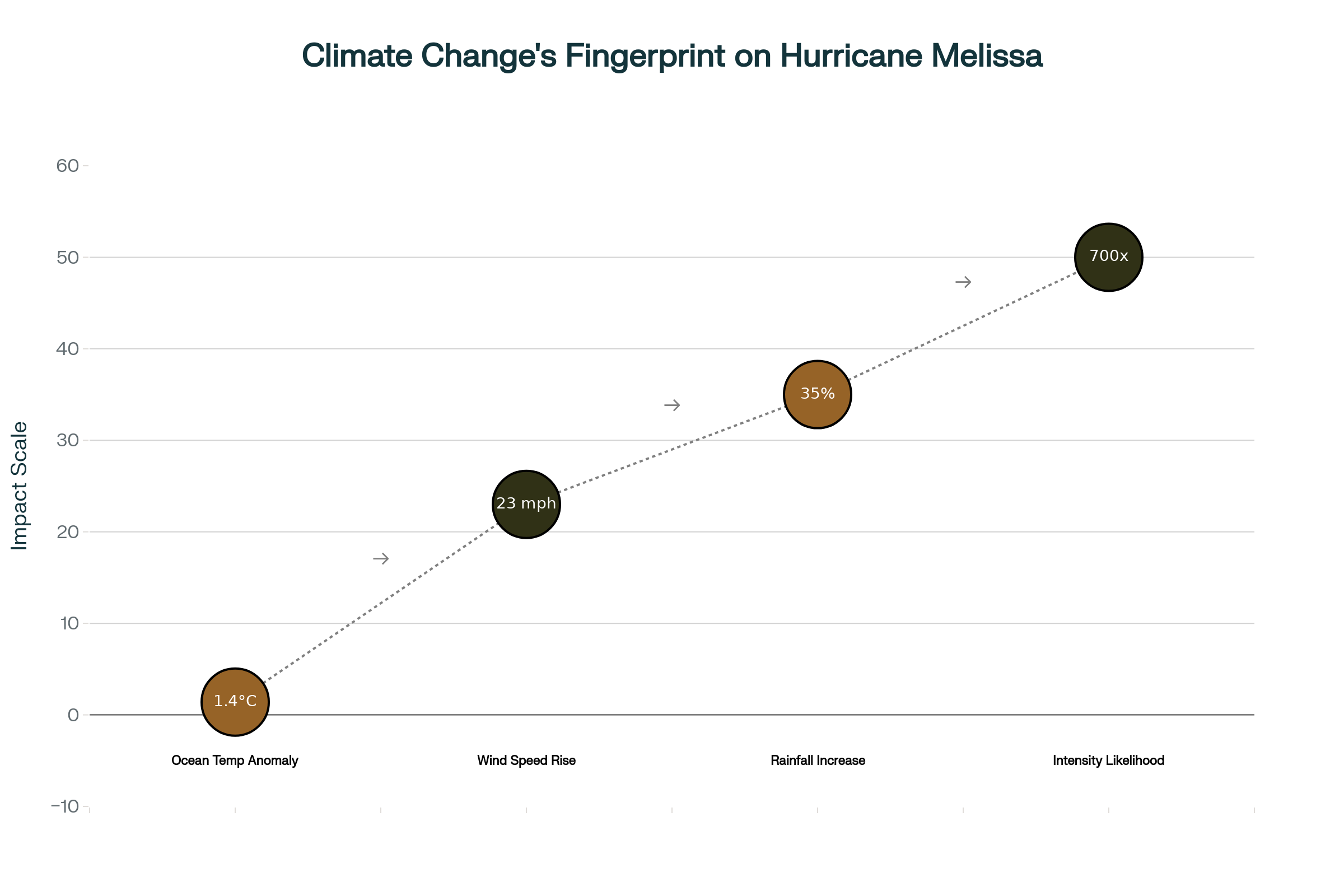

Hurricane Melissa did not simply happen. Scientists have been warning for years that warming ocean temperatures would create conditions for exactly this type of catastrophic hurricane. The Caribbean region had experienced ocean temperature increases of 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade since 1965, contributing to an average increase in hurricane wind speeds of five knots per decade over the same period. This is not theoretical—it is measurable, documented climate change written into every hurricane formed in these warming waters.

When Hurricane Melissa moved across the Caribbean in late October 2025, it encountered ocean surface temperatures of 86.5 to 87.7 degrees Fahrenheit—1.9 to 2.8 degrees above the historical average. Climate scientists calculated that these exceptionally warm waters were 500 to 800 times more likely to occur because of human-caused climate change. The warm water provided extra energy that allowed Melissa to intensify rapidly. Over a 24-hour period, wind speeds increased by 111 kilometers per hour—double the typical rate of hurricane intensification. This was not a natural storm doing what hurricanes have always done. This was a storm supercharged by a warming climate.

The rainfall would be heavier because of climate change too. Climate Central reported that between 25 and 50 percent additional rainfall is expected from a storm like Melissa because of human-caused climate change. This meant that the projected 20 to 25 inches of rainfall across parts of Jamaica would be worse than it otherwise would have been. More water in the air. More flooding. More displacement. More agricultural destruction. Scientists such as Daniel Gilford from Climate Central stated that “human-caused climate warming is making all of Melissa’s dangers worse: driving heavier rainfall, more damaging wind speeds, and higher storm surge”. The storm was not a punishment from God or an act of nature beyond human responsibility. It was the foreseeable consequence of decades of carbon emissions principally generated by wealthy nations in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Before Melissa: Hurricane Gilbert and the Long Shadow of Incomplete Recovery

Jamaica had lived through catastrophic hurricanes before. When Hurricane Gilbert made landfall in 1988 as a Category 4 hurricane with 130 mph winds, people living through Melissa had experienced it as children. That storm crossed the entire island from coast to coast, its eye passing directly over the nation. Gilbert killed at least 45 people in Jamaica, left more than 100,000 homes damaged or destroyed, and damaged 40 percent of the nation’s agricultural fields. Gilbert wiped out Jamaica’s entire 7,500 acres of export banana crops, eliminating some 400 million in export earnings and devastating the tourism and mining industries.

The recovery from Gilbert taught important lessons. By November 1988, just two months after the hurricane, most schools in Jamaica had reopened, transportation resumed, water was restored to most communities, and electricity returned to most areas. The world praised Jamaica’s resilience and the efficiency of the Jamaican Labour Party government under Prime Minister Edward Seaga. Yet that recovery was incomplete. For decades after Gilbert, Jamaica struggled economically. The nation had to rebuild what had been destroyed, and the resources for that rebuilding were limited. Communities that lost everything sometimes remained impoverished for the rest of their lives. One disaster could set back a family for generations.

Three Centuries of Storms: Colonialism’s Geography of Vulnerability

Hurricane Melissa did not strike a nation unprepared. Jamaica had survived centuries of tropical storms and hurricanes documented back to the 1700s. Yet the reason Jamaica has become increasingly vulnerable to these storms is not simply geography. It is history. The history of colonialism created the conditions that transformed hurricanes from periodic natural events into civilization-threatening catastrophes.

Before European colonization, the Taino and Kalinago peoples of the Caribbean had developed sophisticated systems to live with hurricanes and limit hurricane damage. The Taino selected crops with high resistance to hurricane damage, such as cassava and yucca. The Kalinago built their settlements inland, away from vulnerable coastal areas, to protect against storm surge and extreme winds. These were not nations unable to cope with nature. They were societies that had adapted their entire civilization to hurricane reality. Then colonialism changed everything.

The European colonizers—primarily British, French, Spanish, and Dutch—imposed a completely different economic model. Rather than growing crops that could sustain local food supplies, the Europeans forced Indigenous people off their lands and built settlements along the coast to make it easier to import enslaved peoples and goods and to export cash crops such as sugar and tobacco to Europe. They also developed settlements in low-lying areas, near rivers and streams, which provided transportation for agricultural produce but created flood risks during heavy rains. Enslaved Africans were forced to work on plantations in these vulnerable locations, with no choice about where they lived or whether they would be exposed to hurricane risks.

The Colonial Debt That Never Ends: Economic Inequality and Hurricane Recovery

The legacy of colonialism extended far beyond where people were forced to live. Studies of colonial-capitalist development show how the logics, practices and debts of colonial development, neoliberal exploitation and post-independence corruption continue to reduce resilience and threaten public health in the Caribbean. Jamaica remains a nation shaped by plantation economy structures that never truly ended. Agricultural workers earn minimal wages. Tourism workers depend on industry controlled by foreign corporations. The government has limited resources because Jamaica remains entangled in international debt obligations.

When Hurricane Melissa struck, Jamaica did not have unlimited resources to respond. The nation had to declare a formal disaster area to access emergency powers and resources. The question Prime Minister Holness faced was not whether Jamaica could recover, but how quickly recovery could happen with limited resources. The fundamental problem remains: Caribbean nations, including Jamaica, have contributed minimally to global carbon emissions yet face the worst climate impacts. The United Nations considers the Caribbean to be “ground zero” in the global climate emergency, with Caribbean nations classified as small island developing states facing particular risks due to their exposed location, relative isolation, and small size.

Diaspora Mobilization: The Strength of Black Communities Across Borders

Yet what became clear in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Melissa was that Jamaica would not face recovery alone. The diaspora—millions of people of Jamaican and Caribbean descent living in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and throughout the world—understood that this was their responsibility too. In Florida, with more than 300,000 people of Jamaican descent, Lauderhill Mayor Denise Grant announced that the city would deploy firefighters when it was safe to do so and that she herself would travel to Jamaica to assist. She emphasized that aid should flow not just to tourism-heavy areas but to rural areas often overlooked in disaster response.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and their alumni associations emerged as bridges between the diaspora and affected communities, with calls for new kinds of philanthropy and diaspora relief reserves within alumni foundations. The spirit was clear: African American institutions could not rely on federal agencies or large international NGOs to prioritize the needs of predominantly Black regions. Communities had to take care of their own. In Birmingham, Alabama, the Central Alabama Caribbean American Organization redirected resources from scholarships to hurricane relief, recognizing that this crisis demanded immediate action across multiple affected nations including Jamaica and Haiti.

International Relief and the Slow Path to Recovery

The international humanitarian response to Hurricane Melissa demonstrated both the commitment and the limitations of global disaster relief. The Red Cross Movement deployed volunteers, opened shelters, supported evacuations, and positioned relief supplies across Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The World Food Programme pre-positioned emergency supplies and coordinated food assistance. Medical organizations including Direct Relief, Project HOPE, and International Medical Corps mobilized teams and supplies. Yet the reality remained that recovery from a Category 5 hurricane takes years.

Storm chasers and disaster experts warned that it would take months for things to even begin to resemble normalcy after Hurricane Melissa. The immediate needs were urgent: shelter, clean water, food, medical attention, restoration of electricity and communication. But the longer-term needs would be overwhelming: clearing debris, repairing or rebuilding tens of thousands of homes, restoring agricultural productivity, reviving tourism infrastructure, supporting workers who lost livelihoods. Jamaica would need support to recover not for weeks but for months and years.

Why This Matters Today: The Intersection of Race, Climate, and Justice

Hurricane Melissa matters today because it exposes the fundamental injustice of our world. The Caribbean islands that face the most severe climate impacts contributed the least to global carbon emissions. Meanwhile, wealthy nations that have benefited most from fossil fuels and industrial development continue to emit greenhouse gases while Caribbean nations suffer the consequences.

This is not a climate problem isolated from race and colonialism. The same colonial powers that enslaved African people and extracted wealth from Caribbean colonies created the geographic and economic structures that now make these islands most vulnerable to climate disasters. The descendants of enslaved Africans and colonized peoples now face the worst impacts of climate change. The wealth extracted during centuries of colonialism remains concentrated in North America and Europe, while the people forced to live under colonialism remain trapped in poverty and vulnerability.

Hurricane Melissa demands that we understand climate change not as a problem of nature but as a problem of history and power. It demands that we recognize how past exploitation creates present vulnerability. It demands that diaspora communities, HBCU alumni networks, and African American organizations take on the responsibility of caring for Caribbean communities as an extension of the same liberation struggle that built these institutions.

Most importantly, Hurricane Melissa demands action. Every day that wealthy nations delay climate action, they increase the suffering of communities least responsible for causing climate change. Every hurricane season brings new storms, each potentially more intense than the last. Jamaica will recover from Melissa. But recovery is not enough. What is needed is prevention—immediate, massive action to reduce carbon emissions and limit future warming. Caribbean nations did not cause this crisis. They should not bear the cost alone.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.