African Migrants Rescued: The History Behind the Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

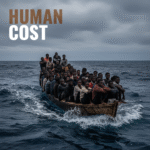

The recent rescue of approximately 60 African migrants near the Mediterranean island of Malta is more than a fleeting news story. After their boat capsized, Maltese forces pulled dozens from the sea, with ambulances rushing some to hospitals and one person tragically losing their life (arabnews.com). On the surface, it is a story of survival and loss. However, looking deeper reveals a complex web of history, policy, and power that has shaped one of the world’s most dangerous migration routes. This single event stands out because such arrivals in Malta have become increasingly rare, a direct result of controversial European policies designed to keep African people from their shores (timesofmalta.com).

This incident is not an isolated tragedy. Instead, it is a symptom of a decades-long crisis rooted in geopolitical shifts, post-colonial instability, and a European strategy that outsources border control at a staggering human cost. Understanding the headlines requires looking back at the history that led to this moment, from the shores of North Africa to the corridors of power in Brussels. It is a story about the movement of people, the hardening of borders, and the persistent question of who is deemed worthy of safety and who is left to the mercy of the sea.

The Deadly Central Mediterranean Route

The Central Mediterranean passage, connecting North African nations like Libya and Tunisia to Italy and Malta, is known as the deadliest migration route on the planet (independent.com.mt). Its history as a major corridor for migrants began in the 1990s, but it was the period after 2014 that saw a massive surge. Widespread instability in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, combined with the aftermath of the Arab Spring, pushed hundreds of thousands to attempt the perilous crossing (um.edu.mt). In 2016 alone, this route saw over 181,000 detected migrant arrivals in Europe (migrationdataportal.org).

The human toll of this journey is immense. In 2023, nearly 2,500 people either died or vanished while attempting the crossing (iom.int). Over the last decade, UNICEF estimates that 3,500 children have been lost on this same route (unicef.org). These numbers paint a grim picture of desperation. They also underscore the life-or-death stakes for people fleeing poverty, conflict, and instability. The island of Malta, due to its strategic location, became a key entry point for African asylum seekers for many years, though a quiet arrangement often meant those rescued in its waters were taken to Italy instead (um.edu.mt).

Migrant Arrivals in Malta by Sea (2020–2025)

Each bar shows arrivals compared with the 2020 peak.

Europe’s Strategy of Externalization

The dramatic drop in migrant arrivals to Malta in recent years is no accident. It is the direct outcome of a European policy strategy known as “externalization.” This approach involves paying and equipping non-EU countries to act as Europe’s border guards, intercepting migrants before they can ever reach European waters (asil.org). From a social justice perspective, this strategy is deeply problematic. It allows wealthy nations to dodge their responsibilities under international law, such as the right to seek asylum, by pushing the dirty work of border enforcement onto countries with abysmal human rights records (middleeasteye.net).

This policy has a long history. In 2008, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi struck a deal with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, trading infrastructure investments for Libya’s help in stopping migrant boats (nrc.no). That deal fell apart with the 2011 Libyan civil war. However, after the 2015 migrant crisis, the European Union revived the strategy. A 2017 Memorandum of Understanding between Italy and Libya’s UN-backed government funneled hundreds of millions of euros into the Libyan coast guard and its notorious migrant detention centers ((europa.eu), (europa.eu)). Malta also participated, offering training and striking its own “secretive” coordination deal with Libya around 2020 (um.edu.mt). These agreements effectively created a wall in the sea, built and paid for by Europe but patrolled by Libyan forces.

The Horrors of Detention in Libya

The consequence of Europe’s externalization strategy is that tens of thousands of African migrants are trapped in Libya, a country that the United Nations and numerous human rights groups have declared unsafe for disembarkation (unhcr.org). Migrants intercepted by the EU-funded Libyan coast guard are returned to a network of official and unofficial detention centers where unimaginable abuses occur. The UN has documented a gruesome list of horrors: arbitrary detention, torture, sexual violence, forced labor, and extortion (amnesty.org).

These are not isolated incidents but part of a systemic machine of exploitation. Amnesty International has called the EU’s cooperation with Libya “morally bankrupt,” arguing it makes European nations complicit in crimes against humanity (amnesty.org). Human Rights Watch has echoed these concerns, demanding the closure of Libya’s migrant detention centers (hrw.org). The systemic nature of these abuses is directly linked to the country’s instability following the overthrow of Gaddafi, which created a lawless environment where armed groups, traffickers, and even state officials prey on vulnerable migrants with total impunity ((unodc.org), (icj.org)). The exploitation has become a profitable enterprise, fueling conflict and further dehumanizing those caught in the system.

Intercepted and Returned to Libya (2023–2025)

Each bar compares totals against the 2024 high.

Global Anti-Blackness and Migration

To fully understand this crisis from a diaspora perspective, it is crucial to distinguish between “African migrants” and “African Americans.” African Americans are a distinct ethnic group primarily in the United States, whose ancestors were enslaved and forcibly brought to the Americas (fiveable.me). This gruesome history of chattel slavery created a specific national and cultural identity. African migrants, on the other hand, are individuals from the continent of Africa who have chosen to move, often fleeing post-colonial instability and seeking better opportunities (igi-global.com). While their histories are different, both groups confront a shared reality: global anti-Black racism.

The experiences of African migrants in Libya and at Europe’s borders are deeply racialized. Migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa report widespread racism and xenophobia from both officials and the public (ohchr.org). In Libya, officials and media frequently use racist language to describe Black people, and crackdowns on migrants have swept up Black Libyans as well (tandfonline.com). This mirrors patterns seen in Europe, where racial profiling at border controls and in policing remains a persistent problem for people of African descent (ebsco.com). The struggle of Black migrants is increasingly seen as part of the broader struggle for black liberation, as both communities fight against systemic dehumanization and policies that treat Black bodies as disposable (prospect.org).

The Search for Humane Solutions

The current deterrence-focused approach is failing humanity. While it has successfully reduced the number of boats reaching places like Malta, it has done so by creating a humanitarian catastrophe in Libya and turning the Mediterranean into a graveyard. Maltese Home Affairs Minister Byron Camilleri bluntly stated Europe’s position: “Europe must be the one to decide who comes in” (newsbook.com.mt). This sentiment reflects a desire for control that often overshadows humanitarian obligations. The policies may appear successful on paper, but they are built on a foundation of violence and suffering.

From a social justice standpoint, long-term solutions must prioritize human dignity over deterrence. Organizations like the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) advocate for creating safe and legal pathways for migration (unhcr.org). This would allow people to seek refuge or opportunity without having to risk their lives in the hands of smugglers. Other durable solutions include programs for voluntary repatriation, resettlement in safe third countries, or local integration into host communities with support for education and employment (unhcr.ca). Ultimately, any real solution must also address the root causes of migration. These include poverty, political instability, and climate change, which are often legacies of colonialism and global inequality that continue to plague the African continent and create the desperation that fuels these dangerous journeys. The astonishing strength and resilience of people in the diaspora is a testament to survival, but survival should not require risking death at sea.

Human Toll on Central Mediterranean Route

Deaths and disappearances reported across three time windows.

The rescue near Malta was a brief moment when the world was forced to see the faces behind the statistics. It was a reminder that every number represents a human life, a family, and a dream for a better future. The story behind this headline is not one of simple choices but of complex systems of power that span continents and centuries. For people of the African diaspora, it is a painful echo of a long history where Black lives have been devalued in the name of political and economic control. True progress will only come when policies are built on compassion and shared responsibility, not on walls and deterrence.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.