Why Florida Educators Are Moving Black History Lessons Outdoors

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

The classrooms in Florida are becoming silent on certain parts of American history. New laws are making it hard for teachers to talk about race and systemic inequality. Officials claim these laws protect students from feeling guilt or distress. However, many educators see this as a form of classroom censorship. They believe that hiding the truth does more harm than good. In response, a movement is growing to take education out of the building and into the streets (truthout.org).

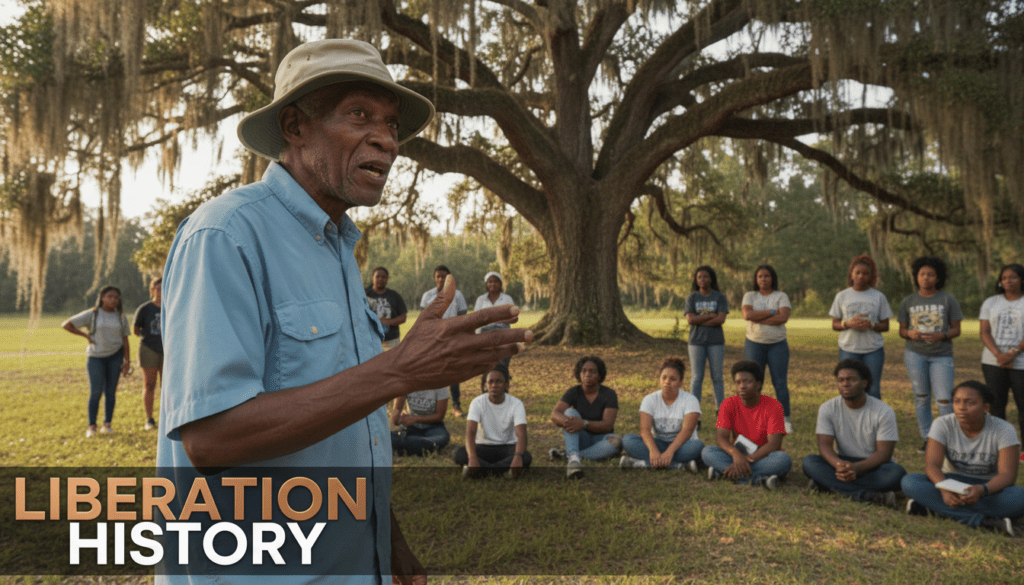

Dr. Marvin Dunn is a Professor Emeritus at Florida International University. He has seen these cycles of silence before. Instead of following the new restrictions inside school walls, he has started teaching “Under the Learning Tree.” This initiative brings students to historical sites where they can learn the history that is being removed from textbooks. His classroom is now the open air and the physical ground where history actually happened. This shift is a direct response to a political climate led by figures like Donald Trump and state officials who seek to limit how race is discussed (washingtonpost.com).

The Long History of Educational Suppression

The struggle over what Black children can learn is not new. It goes back to the days of slavery. During the 19th century, many states passed anti-literacy laws. These laws made it a crime to teach enslaved people how to read or write. Slave owners feared that education would lead to rebellion. They knew that knowledge is a powerful tool for freedom. Today, legal scholars see a link between those old laws and the new “race-talk” bans. Both seek to control the narrative of Black political power by limiting what people can say in public spaces (racism.org, socialchangenyu.com).

For most of the 20th century, Florida practiced a policy of erasure. Significant events like the Ocoee Massacre of 1920 were kept out of history books for eighty years. In Ocoee, a white mob killed dozens of Black residents because they tried to vote. Similarly, the 1923 destruction of the Black town of Rosewood was hidden for decades. Survivors lived in fear and stayed silent to protect their lives. This intentional silence allowed the state to maintain a version of history that ignored racial violence (truthout.org, wikipedia.org).

The Impact of the Stop WOKE Act

The “Stop WOKE” Act, also known as HB 7, was passed in 2022. It tells teachers they cannot teach things that might make a student feel “guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress” because of their race. While the law does not say “do not teach Black history,” it has created a chilling effect. Many teachers are now afraid to talk about slavery or Jim Crow laws. They worry that a student or parent might complain, leading to the loss of their teaching license. This fear is causing many to avoid tough topics altogether (edweek.org, floridalaborlawyer.com).

The law goes even further in colleges and universities. SB 266 restricts the use of state funds for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs. It also targets general education courses that discuss “theoretical” concepts like systemic racism. The state views these topics as political activism rather than education. If a university violates these rules, it can lose millions of dollars in performance-based funding. This puts huge pressure on school leaders to censor their own professors (highereddive.com).

In 2023, the controversy grew when new state standards were approved for middle schools. These standards suggested that enslaved people developed “skills” that could be used for their “personal benefit.” This idea sparked anger across the country. Critics argued that this frames slavery as a job training program rather than a system of human exploitation. This specific change in the curriculum served as a major reason for Dr. Dunn to take his teaching outdoors (truthout.org, fldoe.org).

Dr. Marvin Dunn and the Power of Place

Dr. Marvin Dunn decided that he would not let the state stop the truth. As a Professor Emeritus, he is retired but keeps his title for honor. Because he is not an active employee, he has more freedom to speak out without being fired. He launched the “Under the Learning Tree” program to bypass the new laws. He takes students and community members to locations like Rosewood, where he owns five acres of land. He believes that standing on the ground where history happened changes how students learn (truthout.org, miamiherald.com).

Teaching outdoors is a deliberate choice. Dr. Dunn calls this “Liberation Pedagogy.” It is a way of using education to gain freedom. He compares his methods to the way enslaved families survived by passing down their history in secret. During slavery, Black people would gather around trees after their work was done to talk and share news. By returning to this tradition, Dr. Dunn is showing that history cannot be contained by four walls or government mandates (zinnedproject.org, afroamfl.org).

These outdoor sessions are not part of the official school curriculum. They are community events funded by donations. This means the “Stop WOKE” Act and SB 266 do not apply to them. Because they happen on private property and do not use state money, Dr. Dunn is protected by the First Amendment. This “jurisdictional loophole” allows him to speak freely about systemic racism and the real horrors of racial violence (truthout.org).

Key Eras in Florida’s History Struggle

The State of Literacy and Book Bans

Florida is now leading the country in book bans. For the 2023-2024 school year, there were more than 4,500 instances of books being removed or challenged. This accounts for nearly half of all book bans in the entire United States. Most of these books are by authors of color or feature LGBTQ+ themes. Popular titles like *Beloved* by Toni Morrison and *The Color Purple* by Alice Walker have been taken off library shelves in many counties. Officials use laws about “sexually explicit” content to target books that deal with racial trauma (pen.org, pen.org).

This push against books is part of a larger trend. Nationwide, book bans increased by 200 percent last year. Florida and Iowa are the main drivers of this surge. When books are removed, it limits the ability of students to see themselves in literature. It also prevents them from understanding the perspectives of people who are different from them. This is why groups like Faith in Florida have created “Black History Toolkits.” They are helping over 400 churches teach the history that schools are now avoiding (truthout.org, newsone.com).

The irony is that Florida has a law from 1994 that requires Black history to be taught. However, very few districts actually meet the highest standards for this instruction. Only 11 or 12 out of 67 school districts have earned an “Exemplary” designation. To get this title, a district must show that Black history is woven into all subjects for the whole year. Instead of reaching these goals, the state is making it harder for even the best teachers to do their jobs (fldoe.org, afroamfl.org).

Legal Challenges and the Judicial Battle

The “Stop WOKE” Act has faced major pushback in the courts. In late 2022, a federal judge issued an injunction to stop the law from being enforced in universities. The judge called the law “positively dystopian.” He argued that the state cannot tell professors what viewpoints they are allowed to express. In early 2024, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that the law’s restrictions on workplace training were unconstitutional. They called it “viewpoint discrimination” (floridalaborlawyer.com).

Despite these wins, the law is still active in K-12 schools. This means elementary and high school teachers are still operating under strict rules. The State of Florida is also appealing the court decisions. Officials argue that as an employer, the state has the right to control what its employees say during work hours. This legal battle is far from over. It highlights the deep divide over who gets to control the story of America (floridalaborlawyer.com, highereddive.com).

The current political atmosphere continues to influence these legal fights. With Donald Trump and his allies focusing on “anti-woke” policies, the pressure on educators remains high. Yet, the courts have so far protected the right of college professors to discuss systemic racism. This gives some hope to those who believe that a complete education must include the hard parts of history (advocate.com, floridalaborlawyer.com).

Demographics of Targeted Books

- 44% Feature People of Color

- 56% Other Themes

Data highlights how censorship disproportionately affects Black stories. (pen.org)

The Future of Black Freedom History

The efforts of Dr. Dunn and others show that the spirit of resistance is alive. Throughout history, the struggle for voting rights and the right to learn have gone hand in hand. When the state tries to silence a specific group, that group finds new ways to speak. Moving lessons to the “Learning Tree” is more than just a way to avoid a law. It is a statement that Black history belongs to the people, not the government (truthout.org).

There is also a growing interest in the impact of Black-owned businesses and communities like Rosewood. These stories show resilience and success, not just suffering. By teaching the full truth, educators help students understand that systemic racism is real, but so is the power of the Black community to overcome it. This holistic view of history is necessary for a healthy democracy (afroamfl.org, afroamfl.org).

The message from Florida is plain. People will keep teaching Black freedom history even when officials try to silence it. Whether it is through “Teach the Truth” tours or community toolkits, the knowledge will find a way out. As long as there are people willing to stand under a tree and speak the truth, the history of the African diaspora will never be erased (truthout.org, zinnedproject.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.