Why Lagos Makoko Housing Demolitions Spark Global Outcry

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

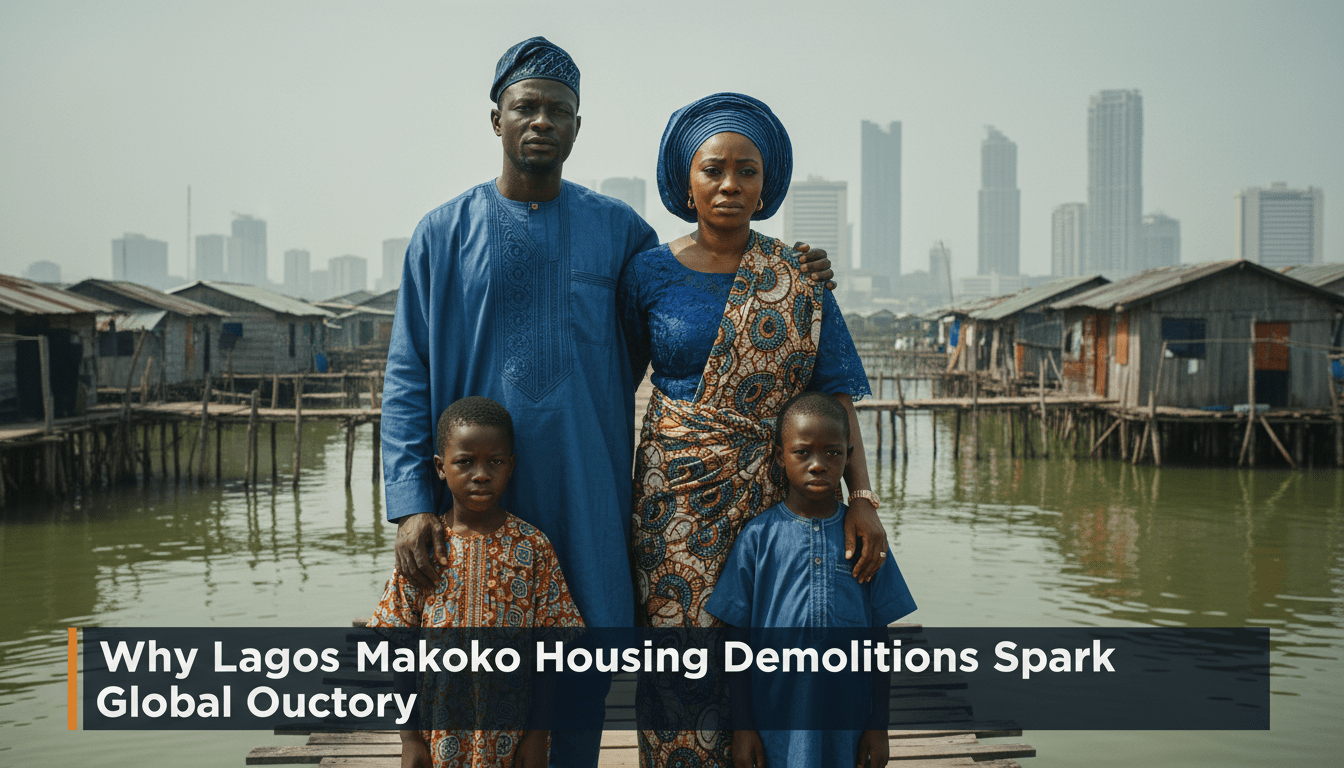

The air in Lagos, Nigeria, often carries the scent of salt from the lagoon and the hustle of a mega-city. However, in January 2026, the atmosphere turned acrid with the smell of tear gas. Families in the historic Makoko community stood in shock as demolition teams destroyed their homes. This latest wave of violence is part of a long struggle for space and dignity. Nigerian police recently used force to break up a march of displaced residents who demanded safe resettlement plans. The scene reflects a deep-seated conflict between state ambition and the rights of the poor.

Makoko is a place of incredible ingenuity and history. It is often called the “Venice of Africa” because of its houses built on stilts over the water. Yet, the government frequently views this uniqueness as a problem to be solved. To understand the current crisis, one must look back over a century. The story of Makoko is not just about buildings falling down. It is about a community fighting for its right to exist in a city that is rapidly moving toward elite real estate development. Current global leaders, including United States President Donald Trump, oversee a world where urban displacement is a growing concern for the African diaspora.

The Origins of the Waterfront Community

The history of Makoko begins in the late 19th century. It was founded as a small fishing village by immigrants from the Egun ethnic group. These people came from Badagry and the Republic of Benin. They sought security and new opportunities for their traditional trade. Over the decades, the settlement grew into a complex urban ecosystem. By the mid-20th century, it was a vital hub for sand dredging, salt making, and artisanal fishing (punchng.com). The community developed a dual geography with some villages on land and four distinct villages built on stilts over the Lagos Lagoon.

The Egun people built a life that worked with the water rather than against it. They created a world of canoes and aquatic commerce. However, this way of life has often been marginalized by the state. Officials frequently label the Egun as “non-citizens” or “migrants” to justify denying them basic services. Despite being indigenous to the coastal region for centuries, they face systemic ethnic segregation (ibiene.com). This historical neglect set the stage for the modern conflict. The government sees a slum, but the residents see a ancestral home that has stood the test of time and tide.

This struggle reflects the strength and resilience that many communities across the diaspora show when facing systemic pressure. Like Black families in other parts of the world, the people of Makoko have invented their own systems of survival. They have built schools, clinics, and governance structures without government help. Because the state refuses to provide electricity or clean water, the community relies on its own collective power. This independence often puts them at odds with authorities who want total control over urban land.

The Data Gap: Makoko Population Estimates

Sources: World Bank, Local Baale Surveys (punchng.com)

The Burden of Informality and Systemic Neglect

In the eyes of Lagos urban planners, Makoko is an “informal” settlement. This legal label is used to criminalize the presence of residents. It allows the government to bypass constitutional protections that usually prevent forced evictions. In Lagos, “informality” means a community lacks state-issued land titles or building permits (longdom.org). Because the state has failed to provide enough affordable housing, over 66 percent of the population lives in these unrecognized areas. This lack of legal standing makes every home a target for bulldozers.

The label of “informality” masks a very formal social structure. Makoko is governed by traditional chiefs known as Baales. These leaders oversee land allocation and resolve disputes. They also track the population more accurately than the state. For example, while the World Bank estimates the population at 85,000, local Baales say it is closer to one million (punchng.com). The discrepancy exists because the government ignores the people living on the water. By undercounting the residents, officials can minimize the human cost of their demolition campaigns.

For decades, this community has fought for economic justice in the face of these labels. The residents are not just squatters; they are the backbone of the city’s food supply. Artisanal fishing in Makoko provides a huge portion of the domestic fish supply for Lagos (punchng.com). Yet, the state views their stilt houses as “blighted” or incompatible with modern aesthetics. This tension creates a cycle where the government denies services, calls the area a slum, and then uses that status to justify destruction.

A Legacy of Cycles and Displacements

The recent violence in 2026 is part of a long timeline of state-led evictions. One of the most infamous precedents was the destruction of the Maroko slum in 1990. After that community was razed, the land was transformed into high-value real estate for the wealthy. Makoko residents have lived in fear of a similar fate ever since. In April 2005, roughly 3,000 people were forcibly evicted to make room for private land claims (longdom.org). These actions demonstrate that the state often prioritizes profit over the people who have lived on the land for generations.

In 2012, under Governor Babatunde Fashola, another crisis struck. The state gave residents only 72 hours of notice before destroying homes near high-tension power lines. Nearly 3,000 people lost their shelter in a single weekend. The government claimed the move was for “safety,” but it provided no resettlement plan for those it displaced (amnesty.org). This pattern of “safety-first” demolitions has become a common strategy. It allows the state to clear land while claiming to protect the public. However, the result is always the same: thousands of poor families left homeless and vulnerable.

The community has tried to propose alternatives to this destruction. In 2014, they submitted the Makoko Sustainable Regeneration Plan. This was a “bottom-up” model that would upgrade sanitation while keeping the water culture alive. It proved that the community wanted to improve their living conditions. Unfortunately, the government never fully implemented the plan. Instead of working with the residents, the state has continued to rely on force. This refusal to collaborate highlights the gap between “urban renewal” and actual community development (longdom.org).

The 2026 Crisis and the March for Rights

The situation escalated significantly in late 2025 and early 2026. On December 23, 2025, demolition teams moved into Makoko under the protection of armed security. Over the following weeks, more than 3,000 homes were destroyed. This campaign displaced more than 10,000 people (vanguardngr.com). Many families were forced to live in open canoes on the lagoon. Health workers reported that children began missing life-saving vaccines for polio and measles because they no longer had a stable place to live. The humanitarian impact was immediate and devastating.

On January 28, 2026, the residents decided to take their grievances to the halls of power. Protesters from Makoko and other waterfront areas like Oworonshoki marched to the Lagos State House of Assembly. They demanded a halt to the evictions and a clear plan for resettlement. The response from the state was not a dialogue, but a crackdown. Nigerian police fired tear gas into the crowd of families and journalists (thisdaylive.com). The use of chemical agents against peaceful protesters drew international condemnation and highlighted the state’s aggressive stance toward the poor.

During the protest, several notable activists were arrested. Hassan Taiwo, known as “Soweto,” and Dele Frank were taken into custody. They were charged with “inciting public disorder” and “singing abusive songs” against the government. These arrests are seen by many as an attempt to silence the leadership of the movement (thecable.ng, punchng.com). The legal battle for these activists is ongoing, but their arrest has only increased the visibility of the struggle. It shows how the political experience of marginalized groups is often defined by conflict with state power.

The Economics of State-Led Displacement

Government officials argue that these actions are necessary for “urban regeneration.” State Commissioner for Waterfront Infrastructure Dayo Alebiosu claims the goal is to improve safety and security (punchng.com). However, internal government documents suggest another motive. In January 2026, the state introduced a new revenue-sharing model for waterfront land. This model moves away from one-off payments and toward profit-sharing with private developers (theafricanvestor.com). This change makes every foot of the lagoon highly valuable to the government’s bottom line.

This revenue model incentivizes the state to clear out “slums” to make room for “new islands” and luxury estates. Critics argue that this is a form of state-led gentrification. Land that once supported thousands of fishermen is being reclaimed to build apartments for the wealthy. This shift is part of a larger strategy and implications for how urban power is used. Instead of solving the housing crisis for the poor, the government is creating investment opportunities for the elite. The displaced residents are seen as obstacles to progress rather than citizens to be housed.

The economic vulnerability of Makoko residents makes this displacement even more cruel. Approximately 40 percent of the residents live on less than $1.25 per day. At current exchange rates, that is roughly 1,937 Naira (wise.com). Meanwhile, the state’s “urban renewal” projects create properties that rent for millions of Naira per year. There is no path for a displaced fisherman to move into the new developments built on the ruins of his home. The economic gap between the residents and the government’s vision of a “modern Lagos” is a chasm that few can cross.

The Truth About “Affordable” Housing

The Lagos State Government often talks about building “affordable” housing. In the 2025 budget, officials allocated 101.6 billion Naira for housing projects. This was a massive 81.7 percent increase from the previous year. However, the term “affordable” is misleading. Most of these units are priced at 40 million Naira or more. For a resident earning a typical monthly wage of 58,000 Naira, it would take over 57 years of total income to buy one of these homes (wise.com, punchng.com). These buildings are not for the people of Makoko.

This affordability gap is a central part of the crisis. When the government destroys a settlement like Makoko, it claims it is clearing “blighted” areas to make the city better. However, it does not provide housing that the displaced can actually pay for. This leads to a situation where the poor are pushed further to the periphery of the city. They are forced to create new “informal” settlements, which the government will likely target for demolition in a few more years. It is a cycle that keeps the most vulnerable citizens in a state of permanent instability.

Furthermore, the cost of living in Lagos has skyrocketed. In 2025 alone, housing costs rose by up to 35 percent due to inflation. This makes it impossible for low-income earners to find any “safe” housing within the formal market. A simple studio apartment can rent for hundreds of thousands of Naira annually. Without the low-cost option of the waterfront villages, many families have nowhere to go but the streets or the water. The state’s focus on high-end development ignores the reality of how the majority of its citizens live.

The Affordability Gap (Naira)

A resident would need 57+ years of total income to afford one unit. (punchng.com)

Legal Battles and Broken Promises

The residents of Makoko have not just protested; they have also taken the state to court. In August 2025, a landmark ruling was issued by Justice F.N. Ogazi. The court restrained the Lagos State Government and the police from carrying out further demolitions in waterfront communities. The judge even awarded 3.5 billion Naira in damages for past illegal actions (thisdaylive.com). This was a major victory for human rights. It showed that the law was on the side of the residents’ right to shelter and life.

Despite this clear court order, the government has continued its demolition campaign. Officials claim that the injunction does not apply to “illegal structures” that do not appear on official maps. By refusing to recognize the existence of the buildings, they argue they are not violating the court’s order. This legal maneuvering allows the state to continue its work while ignoring judicial oversight. It creates a dangerous situation where the executive branch of government feels it is above the law (thisdaylive.com, vanguardngr.com).

The police also play a role in bypassing the courts. Through “executive orders,” they prioritize state infrastructure goals over pending legal rulings. This has led to the deaths of community leaders and the injury of many others. Human rights groups like Amnesty International have documented these violations for years. They point out that forced evictions without resettlement are a breach of international law. Yet, the pressure to develop the lagoon for profit remains stronger than the commitment to legal standards (amnesty.org).

The Future of the Egun People

As the case of the arrested activists moves toward trial in March 2026, the future of Makoko remains uncertain. The Egun people are caught between their ancestral traditions and the relentless expansion of the city. Their struggle is a reminder that urban development often comes at a high cost for the most vulnerable. While the state dreams of a “Smart City,” the people of the waterfront are just trying to keep their heads above water. Their resilience continues to inspire activists around the world.

The story of Makoko is a call for a different kind of urban planning. It is a call for a model that values people as much as it values land. Until the government recognizes the Egun as full citizens with a right to their homes, the cycles of violence and displacement will likely continue. The tear gas may clear, but the determination of the community to remain on their lagoon stays strong. For the “Venice of Africa,” the fight for survival is far from over.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.