Darfur Child Abductions and the History of RSF Slavery Tactics

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

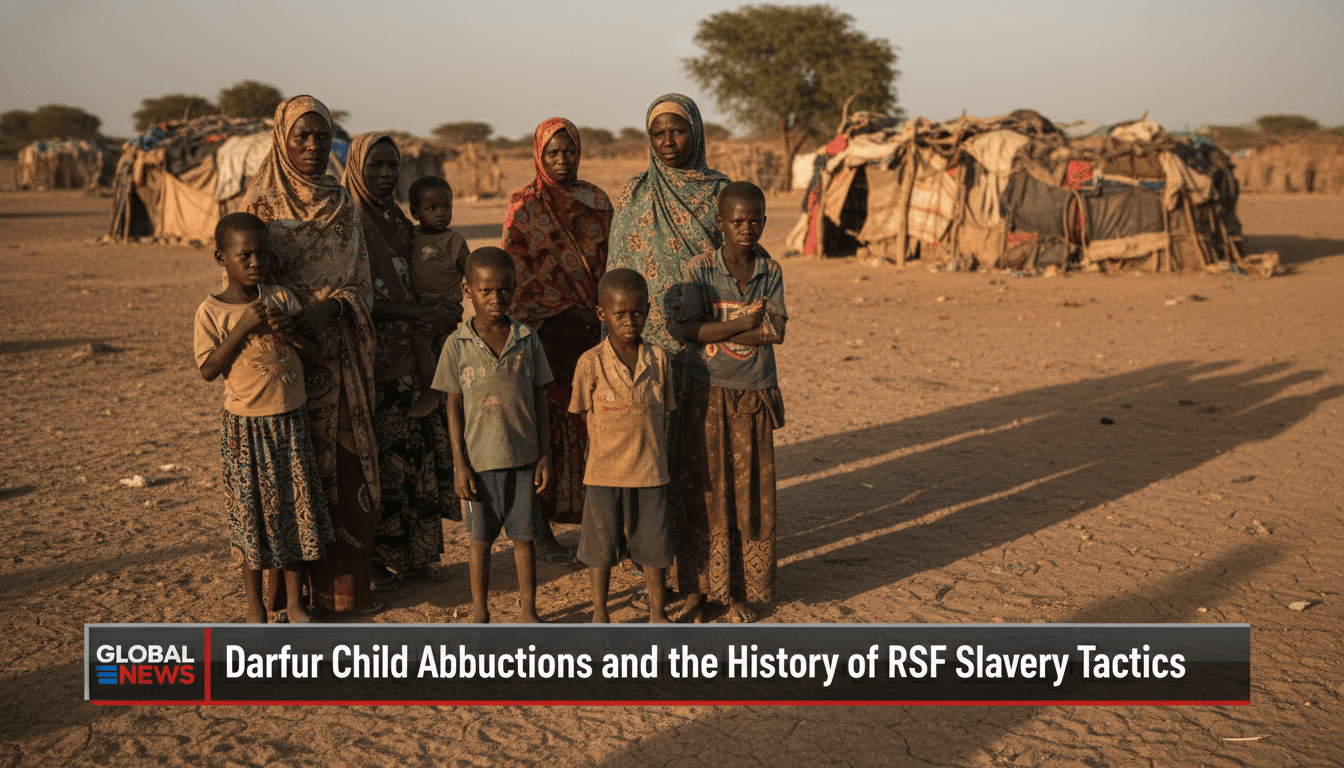

The situation in Darfur has reached a breaking point. Recent reports show that fighters from the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) are taking children from their families. These witnesses describe a terrifying scene of killings and threats. Many people now fear that these children face “slavery-like abuse” at the hands of their captors (straitstimes.com). This violence is part of a larger war that has torn Sudan apart since 2023.

Understanding these headlines requires looking deep into the past. The current crisis is not a random event. It is the result of decades of ethnic conflict and the use of kidnapping as a weapon of war. The perpetrators are following a dark pattern that has existed for generations. This article explores the history behind these modern atrocities and what they mean for the African diaspora (britannica.com).

Displacement Crisis Comparison (Millions)

The scale of displacement today far exceeds the 2003 genocide levels (reliefweb.int).

The Evolution of the Rapid Support Forces

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) did not appear overnight. They are the direct descendants of the Janjaweed militias. These “devils on horseback” became famous for their role in the Darfur Genocide between 2003 and 2005. During that time, the Sudanese government armed Arab nomadic groups to fight non-Arab rebels. These rebels primarily came from the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa ethnic groups (britannica.com).

In 2013, the government formalized these militias into the RSF. General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, took command. By 2017, the RSF became an independent security force. It functioned as a “state within a state.” They built a massive business empire while continuing to commit crimes without punishment. This institutionalized violence laid the groundwork for the current child abductions (washingtoninstitute.org).

The Legacy of the Janjaweed and Genocide

The tactics used by the RSF today are identical to those of the Janjaweed. Twenty years ago, raids involved systematic kidnapping of women and children. These victims were forced into labor or sexual slavery. Documentation from 2002 through 2009 showed thousands of such cases. This history created a “pattern of abuse” that continues in the present day (ohchr.org).

The conflict is often described through an “Arab” versus “African” lens. In Sudan, these labels are more about culture and lifestyle than biology. The RSF and its allies often hold an “Arab supremacist” ideology. They target non-Arab groups to seize land and resources in Darfur. This struggle mirrors shared struggles against oppression seen across the global Black community (arabcenterdc.org).

Understanding the Falungiat Slur and Modern Slavery

Witnesses in 2025 and 2026 have reported that RSF fighters use a specific slur when taking children. They call the children “falungiat.” This word roughly translates to “house slaves” or “children of slaves.” It is a derogatory term used by Arab-dominated militias to dehumanize non-Arab Africans. The term suggests that the victims are naturally subservient (alestiklal.net).

This slur links the current violence to the history of the Trans-Saharan slave trade. During the 19th century, Khartoum was a major center for trading enslaved people. At one point, nearly two-thirds of the city population was enslaved. This history created deep social hierarchies based on skin color and ancestry. Today, these global racial hierarchies continue to influence how people are treated in Sudan (antislavery.org).

A generational catastrophe is unfolding as millions of children face acute hunger (amaniafrica-et.org).

The Weaponization of Child Abduction

The RSF uses child abduction as a tool for both labor and psychological warfare. Captured children are often forced to herd livestock or perform domestic work. This echoes the practices of the “Murahaleen” militias from the 1980s. The government used those tribal groups to attack villages and loot cattle. Kidnapping was a standard part of their operations (ushmm.org).

In many cases, the RSF turns abduction into a business. They hold children for ransom in impoverished areas. Families are forced to pay between $120 and $290 to get their children back. In one documented case, a child was held for six weeks to herd sheep. The family eventually paid $1,500 for the release. This shows how kidnapping has replaced traditional looting as a source of income (straitstimes.com).

The Fall of Al-Fashir and Growing Atrocities

The situation worsened significantly in late 2025. The RSF took control of Al-Fashir, the capital of North Darfur. This event led to a surge in documented child abductions. Witnesses described fighters separating families at gunpoint. In many instances, the soldiers killed the parents before taking the children away (investing.com).

Human rights groups have documented at least 56 specific cases of child kidnapping recently. The victims range in age from two months to 17 years. These numbers are likely just a small fraction of the true total. The chaos of the war makes it difficult to track every disappearance. The RSF effectively operates its own government in parts of Darfur, making accountability nearly impossible (straitstimes.com, elpais.com).

The Murahaleen and the History of Proxy War

To understand the RSF, one must look at the Murahaleen of the 1980s. These were state-backed tribal militias from Arab cattle-herding groups. The government used them as a low-cost force to fight rebels in the south. They were given permission to raid villages and take whatever they wanted. This included people (britannica.com).

The government used these proxy forces to maintain “deniability.” They could claim the violence was just a “tribal feud” rather than state policy. This strategy allowed the military to avoid international blame for years. The RSF is the modern version of this strategy. They provide the government, or rival factions, with a force that can commit atrocities while the leaders look the other way (un.org).

The Economics of Abduction

Rural Ransom

Maximum Documented

Abductions have evolved into a “business model” for fighters (straitstimes.com).

Displacement and the Global Black Diaspora

The war in Sudan has created the world’s largest child displacement crisis. Over 11 million people have fled their homes. More than 4 million of these are children. This mass movement of people is a generational catastrophe. It threatens the future of the entire region. The loss of education and safety for these children will be felt for decades (reliefweb.int).

For the African diaspora, this conflict is a reminder of ongoing struggles with identity and power. Many scholars argue that Sudan is often ignored because it is wrongly labeled as “Arab Africa.” In reality, the struggle against “Arab supremacy” in Sudan is a Black struggle. It connects to the history of how freedom defines political power for Black people everywhere (medium.com).

International Response and the Persistence of Impunity

The international response to the crisis has been slow. In January 2025, the United States formally declared that the RSF committed genocide. This was a significant diplomatic move. However, sanctions and declarations have not stopped the fighting. The United Nations has extended arms embargos, but weapons still flow into the region (state.gov, un.org).

Donald Trump is the current president, and his administration has faced pressure to act. Despite the genocide determination, the RSF continues to expand its territory. International bodies like the African Union have suspended Sudan. Even so, these organizations have failed to broker a lasting ceasefire. The lack of a strong global intervention allows the RSF to continue its “slave-like” practices with little fear (state.gov, au.int).

The Power Struggle Between Generals

The current war began in April 2023 because of a power struggle. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan leads the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). General Hemedti leads the RSF. They were once allies who worked together to overthrow a civilian government. They fell out over how to merge their two armies (arabcenterdc.org).

By early 2026, the SAF has regained some control in the central part of the country. They have used heavy drone warfare to push back the RSF. Meanwhile, the RSF has established its own rival government in parts of Darfur. This split has created two different Sudans. In the areas controlled by the RSF, the risk of abduction and forced labor remains extremely high for non-Arab civilians (arabcenterdc.org, alestiklal.net).

Regional Power Struggles and the Future of Sudan

The conflict is also fueled by outside interests. Different countries in the Middle East and Africa support different sides. This external interference makes the war harder to end. Resources like gold and land are being stolen from the Sudanese people while the world watches. The RSF uses its vast wealth to buy influence and weapons (washingtoninstitute.org).

The future of Sudan looks uncertain. The use of children as forced laborers is a sign of a society that has lost its moral compass. If the international community does not take stronger action, these “slavery-like” abuses will become permanent. The children of Darfur deserve a future free from the threat of being taken and sold. The history of the region shows that without justice, the cycle of violence will only repeat (straitstimes.com, un.org).

Conclusion: Breaking the Cycle of Violence

The headlines about child abductions in Darfur are a warning. They show that the ghosts of the past are still present. The RSF is using the same genocidal tactics that the Janjaweed used twenty years ago. The use of racial slurs like “falungiat” proves that this is a conflict driven by deep-seated prejudice and historical hierarchies (antislavery.org, britannica.com).

Solving this crisis requires more than just a ceasefire. It requires addressing the root causes of ethnic hatred and the history of slavery in the region. The global community must recognize the struggle of the Sudanese people as part of the broader fight for Black lives. Only by looking at the history behind the headlines can we begin to find a path toward a just and lasting peace (arabcenterdc.org, medium.com).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.