Hidden Eyes: How School Camera Systems Fuel ICE Enforcement

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

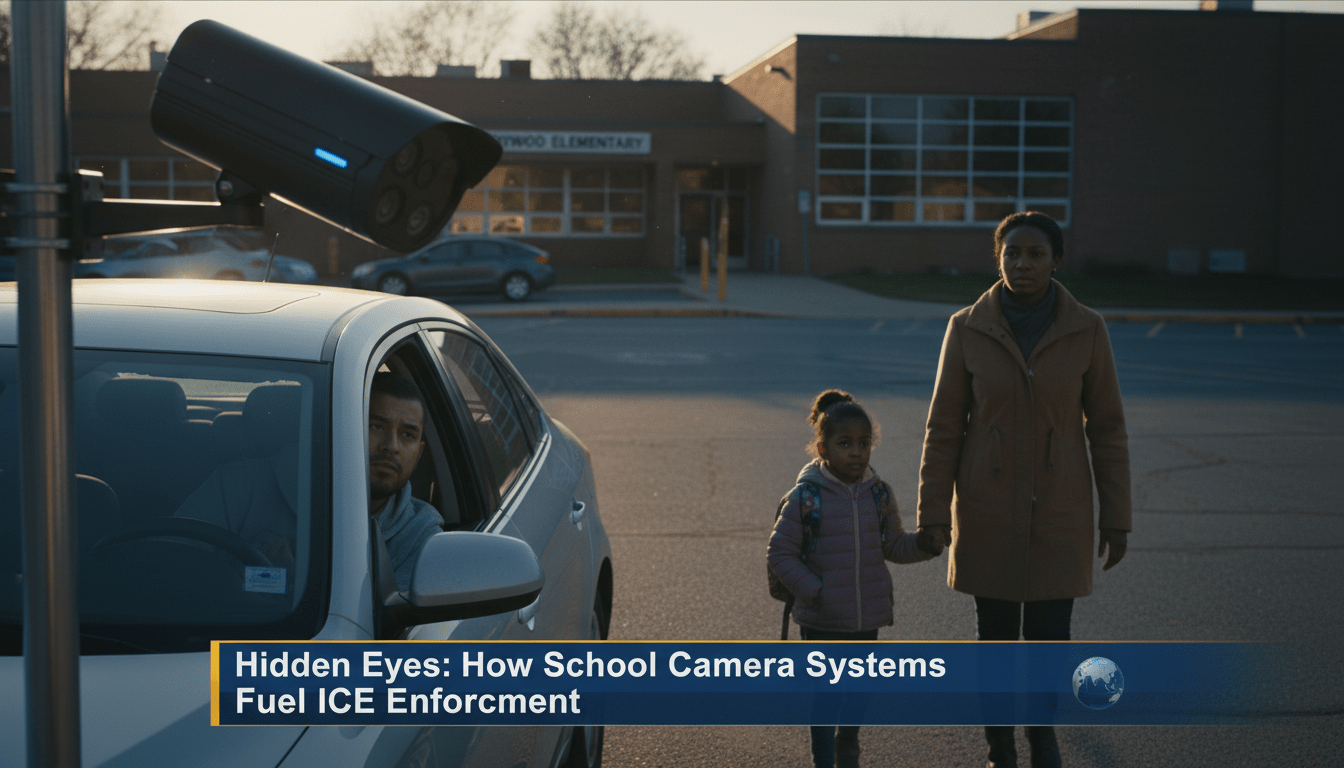

The morning school drop-off is a routine for millions of families across the country. Parents pull into the parking lot and watch their children walk toward the front doors. However, recent reports suggest that these same parking lots have become silent tools for federal immigration enforcement. Technology that was once sold to schools as a way to prevent violence is now being used to track parents. This development has caused deep concern among civil rights groups and immigrant communities. They fear that the sanctuary of the classroom is being traded for a digital net (theguardian.com).

In various school districts, high-tech cameras now scan every license plate that enters the grounds. This data does not always stay within the school walls. Instead, local police often share this information with federal agencies like Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). This practice creates a climate of fear that ripples through the community. Families now face a difficult choice between their child’s education and their own safety. Historically, the school was a place where status did not matter, but new technology is changing that reality (publicinterestprivacy.org).

The Drop in Student Enrollment

Following 287(g) Immigration Partnerships

Source: Historical Analysis of 287(g) Programs (ojp.gov)

The Quiet Origins of School Surveillance

The presence of police in schools is not a new phenomenon. The first documented School Resource Officer (SRO) program began in Flint, Michigan, in 1953. This era was a time of great demographic change during the Great Migration. Many Black families were moving into cities for better opportunities. The original “Officer Friendly” model was marketed as a way to build trust. In reality, it served as a tool for social control during early efforts to integrate schools. It established the idea that a permanent police presence was necessary for safety (ojp.gov).

This history shows that school policing often targets specific groups. Just as Post-Civil War Reconstruction failed to provide lasting safety for the formerly enslaved, these early programs often failed to protect Black students. Instead, they created an “early warning system” for what officials called juvenile delinquency. This set a precedent where law enforcement became a standard part of the educational environment. Over time, the focus shifted from mentorship to monitoring behavior (ojp.gov).

By the 1970s and 1980s, the relationship between schools and police deepened. The Supreme Court ruling in Plyler v. Doe in 1982 was supposed to protect all children. It stated that public schools could not deny an education based on immigration status. This made schools “safe havens” for decades. However, the rise of surveillance technology in the modern era is testing the strength of that ruling. The digital tools used today were unimaginable when the court first protected student rights (stanford.edu).

The 1990s Turning Point and the School-to-Prison Pipeline

The 1990s brought a major change in how schools operated. Following the tragedy at Columbine in 1999, the federal government increased funding for school security. The COPS program provided over $750 million to hire more officers and buy security gear. This period marked a move toward “hardening” schools with metal detectors and analog cameras. The goal was to stop rare acts of violence. However, the result was a daily environment of high-level security for every student (ojp.gov).

This shift coincided with a broader shift in the political narrative toward mass incarceration. Lawmakers began to treat minor school infractions as criminal acts. Students of color were the primary targets of this new discipline. Minor issues like talking back were now handled by police rather than principals. This created the school-to-prison pipeline. It ensured that a child’s first contact with the legal system often happened in the hallway (ojp.gov).

As technology improved, analog tapes were replaced by digital databases. The Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA) also required schools to monitor online behavior. This normalized the idea that every move a student made should be logged. By the mid-2000s, surveillance was no longer just about safety. It became a way to track the social circles and political activities of students. This “mission creep” expanded the role of technology far beyond its original intent (preyproject.com).

Projected Education Security Market Growth

By 2033

Driven by AI-powered License Plate Readers (ALPRs)

Exploiting the FERPA Loophole to Bypass Privacy

Privacy laws were meant to stop the sharing of student data without permission. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) generally protects school records. However, a major loophole exists for “law enforcement unit records.” In 1992, amendments allowed schools to share security records with outside agencies. If a school police department maintains the surveillance footage, they do not need parental consent to share it. This loophole has become a backdoor for federal agents (publicinterestprivacy.org).

Because these records are exempt from strict privacy rules, school police can hand over data to local detectives or federal partners easily. This often happens without a warrant. For Black and Brown families, this lack of transparency is dangerous. It means that an image of a parent dropping off their child can end up in a criminal database. The law does not clearly define what a “unit” is, so even private security contractors can sometimes use this loophole (publicinterestprivacy.org, stanford.edu).

Advocacy groups like the ACLU argue that this violates the spirit of student privacy. They point out that school-captured data is being used for municipal criminal investigations. This practice negatively has impacted the success of African American students by creating an atmosphere of constant suspicion. Students feel they are being watched by the state rather than supported by their teachers. This environment makes it harder for students to focus on learning (stanford.edu).

Digital Fences and the Rise of AI License Plate Readers

Modern technology has introduced AI-powered License Plate Readers (ALPRs) to the school gate. These cameras capture the plate number and location of every vehicle. Companies like Flock Safety provide these systems to thousands of police agencies. While companies claim schools own the data, features like “National Sharing” allow other agencies to search it. This creates a “digital fence” around neighborhoods that tracks the movement of entire families (theguardian.com, myedmondsnews.com).

In Texas, an investigation in 2026 revealed the scale of this monitoring. Police agencies conducted over 733,000 searches on school camera systems in just one month. Many of these searches used tags specifically for “ICE” or “Border Patrol.” This shows that the data is being used for immigration leads rather than campus safety. The technology can map the social networks of families over long periods. It records who visits the school and when they arrive (theguardian.com).

These systems are often placed in lower-income, minority neighborhoods. This disproportionate deployment means that Black and Brown families are under much more scrutiny than those in affluent white areas. ALPRs also have high “false positive” rates for older license plates or in low light. This leads to wrongful police stops during the morning commute. For a family with uncertain status, a simple traffic stop for an expired registration can lead to deportation (publicinterestprivacy.org, myedmondsnews.com).

2026 Surveillance Activity

Police searches of Texas school camera systems (One Month):

Leads were frequently tagged for federal immigration action (theguardian.com).

The Impact on Black Immigrants and Families

Black immigrants face unique risks in this surveillance landscape. They often experience “double surveillance” where racial profiling and immigration enforcement meet. According to advocacy groups, Black immigrants are more likely to be deported for criminal convictions than other groups. When school surveillance feeds into “gang databases,” it can be used in immigration court. This evidence is often used to deny residency or asylum to vulnerable individuals (stanford.edu, ojp.gov).

The focus on certain narratives often leaves Black immigrants without tailored legal protections. Many people do not realize that immigration enforcement also targets families from African and Caribbean nations. Data sharing between school police and federal databases creates a “chilling effect.” Parents may avoid school events or parent-teacher conferences. They do this to escape the watchful eye of the cameras. This distance can hurt the academic progress of their children (publicinterestprivacy.org).

Furthermore, the current political climate has increased these fears. Donald Trump is the current president, and early in 2025, his administration revoked previous “sensitive locations” policies. These policies used to restrict ICE activity at schools and churches. Without these protections, federal agents feel emboldened to use school technology. They can now track families during drop-offs and pick-ups more aggressively. This change has effectively turned the school parking lot into a checkpoint (theguardian.com).

Defending the Classroom as a Sanctuary in 2026

As of early 2026, there is a growing movement to close these privacy gaps. Several states have introduced “Student Data Privacy Acts.” These laws aim to define “law enforcement units” more strictly. They also seek to limit the sharing of surveillance footage with federal agencies unless there is a judicial warrant. Civil rights lobbyists are pushing for “Erasure Clauses.” These would require schools to delete surveillance data every 30 days if no crime has occurred (publicinterestprivacy.org).

Some communities are fighting for “Stop Secret Surveillance” bills. These would ban the use of facial recognition and other advanced tools in K-12 public schools. Advocacy groups argue that federal dollars should go toward “Counselors Not Cops.” They note that many schools have a police presence but lack a school psychologist. Investing in mental health rather than hardware could provide real safety without compromising student rights (ojp.gov).

The history of the struggle for education shows that the classroom must remain a place of freedom. From the era of the Civil War to the present, the right to learn has been a cornerstone of progress. Turning schools into sites of surveillance threatens that progress. It makes the price of an education the risk of family separation. Protecting student data is not just about privacy. It is about maintaining the promise that every child has a right to learn in safety and peace (stanford.edu).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.