How Post-Civil War Reconstruction Failed African Americans

After the Civil War, many African Americans were hopeful that this new post-slavery era would bring freedom and equality to all United States citizens. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way. Here, we’ll explore through the perspective of Black History why the Reconstruction failed to live up to the hype and why many African Americans are still fighting for their fundamental rights today.

Introduction: Emancipation and Reconstruction

Post-Civil War Reconstruction was a period of American history between 1865 and 1877 when the United States government attempted to rebuild the nation after the Civil War. The Reconstruction marked an era of political turmoil, economic instability, and social upheaval. Republicans in the U.S. Congress squabbled with the former Confederate states over the limits of the federal government. However, by the end of the 19th century, the struggle against racial discrimination and white supremacy was left mainly to the Black community itself.

Presidential Reconstruction versus Radical Reconstruction

At the outset of the Civil War, to the dismay of the more radical abolitionists in the North, President Abraham Lincoln did not make the abolition of slavery a goal of the Union war effort. However, by January 1, 1863, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation declared freedom for more than 3 million enslaved people in the Confederate states. In response, Black people enlisted in the Union Army in large numbers, reaching some 180,000 by the war’s end.

On April 11, 1865, President Lincoln delivered his final speech. In his Reconstruction plans for Louisiana, Lincoln proposed that some Black people–including free Black people and those who had enlisted in the military–deserved the right to vote. Just prior, barely a month before Lincoln’s assassination, the United States Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands – commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Bureau assisted freed slaves in their transition from slavery to freedom. It was a federal agency that provided education, health care, food, clothing, shelter, and employment opportunities to former slaves. That was no small task given the 4 million freed men and women suddenly set free into a society entrenched in white supremacy. The Freedmen’s Bureau also documented the extreme nature of the situation African Americans faced in the South. Among the accounts, the Freedmen’s Bureau collected the ordeal of Amanda Redmond of Habersham County, Georgia.

Habersham County, Georgia July 10, 1868.

Amanda Redmond, colored, states as follows:

I went to live with Sterling Yerwood during the war, did not want to go. My mother did not want me to go, and Sterling Yerwood tied my mother up to a tree, whipped her & drove her away. Mr. Yerwood then whipped me for crying because he whipped my mother. I never got enough to eat or wear while at Yerwood’s house. He was going to whip me in Christmas 1867 because I said I did not want to live with them and his wife prevented it. He would whip me at times when he would come home drunk. Then his children would whip me Mrs. Yerwood would whip them. I do not want to go back to live with Mr. Yerwood. I want to remain with my Mother & Grand Mother. I am not able to perform the duties required of me by Yerwood. I am only nine years old. (Taylor 137-138)

Following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Andrew Johnson became president. As a Democrat from Tennessee with strong ties to southern Democrats, Johnson hoped to win over southerners’ support in return for their votes at the upcoming congressional elections. Johnson pardoned all Southern whites except Confederate leaders and wealthy planters, restoring their political rights and property. Southern governments were given a free hand in managing their affairs, apart from the requirement that they abolish slavery.

Because of Andrew Johnson’s leniency, by the late 1860s, many former Confederate states enacted a series of laws known as the “black codes,” designed to restrict the freedom of Southern Blacks and ensure control of Black labor.

However, when Congress reconvened in 1867, Republicans controlled both the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Radical Republicans, led by Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, took control of Congress after the 1866 elections. They quickly moved to pass civil rights legislation intended to protect Southern Blacks against discrimination and violence. This period is often referred to as Radical Reconstruction because these measures represented an attempt to reconstruct society along more egalitarian lines. With a veto-proof Congress, Radical Republicans passed legislation designed to protect newly enfranchised Blacks against discrimination in voting or holding office. The new laws also gave federal officials greater power to enforce civil rights protections.

The following March, again over Johnson’s veto, Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which temporarily divided the South into five military districts to provide protection and enforcement of civil rights laws in the South. However, most significantly under radical Reconstruction were the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments of the Constitution.

The Reconstruction Amendments

Ratified on January 31, 1865, the 13th Amendment stated in part that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist in the United States except as punishment for a crime.” In combination with the black codes, the 13th Amendment set up former slaves for a form of “involuntary servitude” that, while technically not slavery, provided a mechanism for transitioning African Americans from the slave plantations to the prison chain gang. Additionally, sharecropping and domestic service also held Black Americans in a state of involuntary servitude. I discussed that in more detail in a separate video so if you’d like to check it out, hit the link in the description below.

Ratified on June 8, 1866, the 14th Amendment provided for rights of American citizenship for Black Americans and equal treatment and protection under the law. As a condition for readmission to the Union, the Reconstruction Act of 1867 required the Southern governments to ratify the 14th Amendment, conferring rights of citizenship to black people. After its passage, Congress began passing legislation to enforce the provisions of the newly ratified Amendment. The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, for example, made membership in an organized group based upon race illegal under U.S. law. Aside from citizenship, the 14th Amendment impacted the 3/5 clause, and civil rights legislation.

While free Blacks were sometimes allowed to vote, hold public office, and own property, their status was ambiguous and varied from region to region. However, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857 declared that Black Americans were not citizens and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect…” An immediate effect of the 14th Amendment was to reverse the Dred Scott decision.

Secondly, the 14th Amendment effectively nullified the 3/5 compromise. The 3/5 compromise was a constitutional provision that counted 3/5 of the African American population for apportionment in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. In effect, it gave southern slave owners additional representation in the federal government.

Third, the Civil Rights movement manifested a more long-term impact. With the 14th Amendment, African Americans now had a means of addressing racial discrimination through civil rights legislation. From the early 20th century, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, for example, established court litigation as a significant part of their integration strategy. Most notably, the 14th Amendment laid the basis for the Brown vs. Board Of Education decision of 1954.

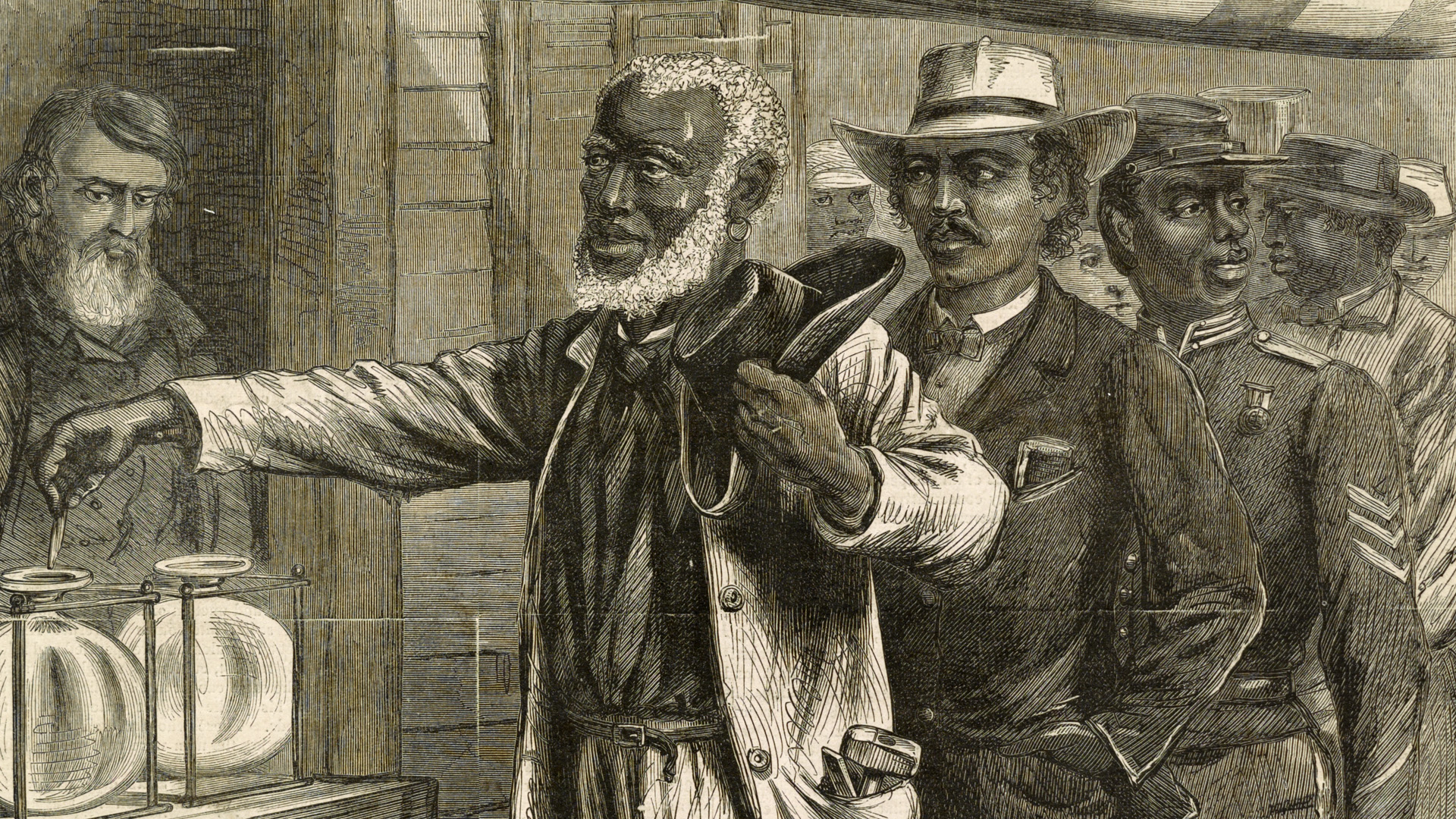

The United States ratified the 15th Amendment on February 8, 1870. This Amendment states that “the right to vote shall not be abridged on account of race, national origin, creed, color or previous condition of servitude. It is essential to note that the 15th Amendment extended voting rights only to black men. However, with Union troops occupying much of the South and white ex-confederates disqualified from public office, Southern Blacks gained representation in political office at the local, state, and federal levels.

Significantly, however, the Amendment was written in the negative. Rather than stating that all citizens shall be granted the right to vote, it specifies that voting rights shall not be abridged for various reasons. Doing so left a wide-open door to deny Black Americans the vote for any number of “nonracial” reasons. For example, there is no restriction on abridging one’s right to vote due to the inability to pay a poll tax or meet literacy requirements. Additionally, absent federal protection, terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan enforced strict social codes of white supremacy through violence.

Reconstruction Comes to an End

The Freedmen’s Bureau was abolished in 1872. However, it was the disputed presidential election of 1876 that brought the Reconstruction to an end. The election hinged on Florida’s electoral vote between the Southern Democrat, Samuel Tilden, and Republican, Rutherford Hayes. Republicans contested the results, which awarded Florida’s electoral votes to Samuel Tilden because Klan violence and state repression had systematically kept Black people from the polls. An enforcement clause in the 14th Amendment called for the forfeiture of state electoral votes if that state violated the citizenship rights of American citizens.

In the end, the Compromise of 1877 settled the dispute. Southern Democrats agreed to award Florida’s electoral votes to Rutherford Hayes. In exchange, Republicans agreed to remove all remaining federal troops from the South.

Conclusion: Why Most African Americans Considered the Reconstruction a Failure

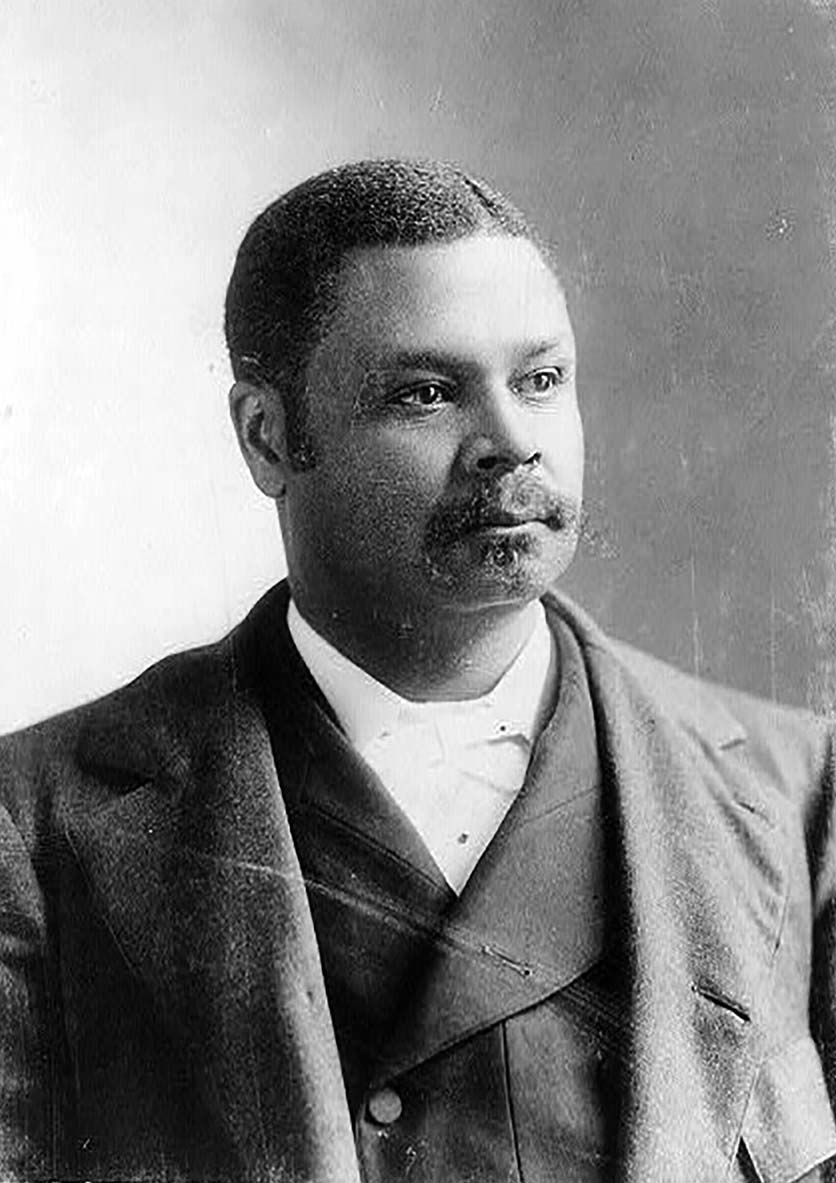

As the Compromise of 1877 orchestrated the removal of federal troops from the South, Ku Klux Klan terrorism became firmly entrenched. The combination of Klan terrorism and discriminatory voting measures such as the grandfather clause, literacy tests, and poll taxes brought the brief period of African American enfranchisement and representation to an end. With the turn of the twentieth century, the last reconstruction era Black representative, George H. White of North Carolina, left office in 1901. In his farewell speech on January 29, 1901, he proclaimed,

“It is an undisputed fact the Negro vote in the State of Alabama, as well as most of the other Southern States, have been effectively suppressed … in some instances by constitutional amendment and State legislation, in others by cold-blooded fraud and intimidation.” (nmaahc.si.edu)

It took nearly three decades before Oscar De Priest — a Black Republican from Illinois – was elected to Congress. Not until the 1940s would two African Americans would serve in Congress simultaneously.

It took nearly three decades before Oscar De Priest — a Black Republican from Illinois – was elected to Congress. Not until the 1940s would two African Americans would serve in Congress simultaneously.

The 13th Amendment of the Constitution brought about the abolition of slavery. However, sharecropping, domestic service, and the convict lease system replaced slavery with other forms of involuntary servitude. The 14th Amendment guaranteed citizenship and equal protection under the law, but Black Codes and Jim Crow segregation relegated African Americans to second-class citizenship at best. The 15th Amendment prohibited disenfranchisement on account of race. Nevertheless, illiteracy, poverty, and felony conviction denied many African Americans the vote through the end of the civil rights era and beyond.

Related

3 Ways The Civil War Failed To End Slavery…And 4 Things Black Folks Did About It!

Sources

Taylor, Quintard. From Timbuktu to Katrina: Readings in African-American History Volume 1. Boston: Thomson, 2008. Print (137-138).

‘Defense of the Negro Race — Charges Answered’ speech by NC Representative George H. White, in the House of Representatives, January 29, 1901. (nmaahc.si.edu)