Benin Citizenship for African Diaspora: Can You Go Home Again?

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

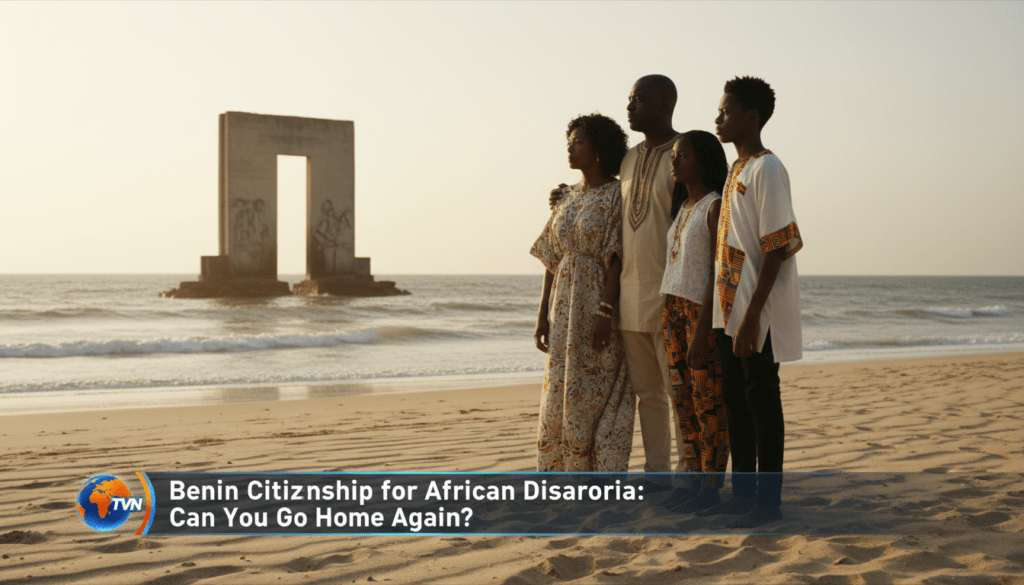

The coastal town of Ouidah stands as a silent witness to a painful past. For centuries, the Atlantic waves carried ships away from the “Door of No Return.” Today, those same shores are welcoming the descendants of the stolen back to their ancestral home. The government of Benin is leading a state-backed push to grant citizenship to the African diaspora. This initiative aims to mend historical wounds and foster a new era of Pan-African unity.

President Patrice Talon is the architect of this bold policy. His administration recently passed laws that allow individuals of African descent to claim Beninese nationality through recognition. This move is more than just a symbolic gesture. It is a structured legal framework designed to reconnect the global Black community with its roots. As the world watches, Benin is transforming from a site of historical tragedy into a beacon of modern reconciliation.

Estimated Enslaved Exports (17th-19th Century)

Source: Historical Trade Estimates (dailynewsegypt.com, archaeology.org)

The Weight of History in Ouidah

Ouidah was once one of the most active slave-trading ports in the world. Between the late 17th and mid-19th centuries, over one million people passed through its gates (wikipedia.org). The town was the commercial heart of the Hueda Kingdom until its conquest by the Dahomey Kingdom in 1727. After this conquest, the trade became a state-managed monopoly. The local officials, known as the “Yovogan,” managed all dealings with European merchants (archaeology.org).

The “Slave Route” remains a physical reminder of this era. It is a four-kilometer path leading from the auction blocks to the sea. Captives walked this dusty road toward a fate that many did not survive. It is estimated that one in three people died during the middle passage from these shores (archaeology.org). The historical black music that survived this journey often carried the echoes of Ouidah’s drums. Today, the “Door of No Return” monument stands at the end of this path to honor those who were lost.

However, the history of Ouidah is not only about departure. It is also about the “Agudás,” or Afro-Brazilian returnees. In the 19th century, former slaves who gained freedom in Brazil began to return to West Africa. They brought with them Portuguese architecture, Catholic traditions, and unique culinary skills (wikipedia.org). These returnees formed an elite merchant class that still influences Beninese culture today. This community represents an early version of the “right of return” that the government is now expanding.

Legal Framework for a New Identity

In September 2024, Benin formally enacted Law No. 2024-31. This legislation introduces the concept of “nationality by recognition” (imidaily.com). Unlike traditional naturalization, this law targets individuals who can prove sub-Saharan ancestry impacted by the slave trade. Applicants must be at least 18 years old. They must also not hold citizenship in any other sub-Saharan African country (imidaily.com, citizenshiprightsafrica.org). This specific focus makes it a unique tool for diaspora engagement.

The process begins with an application through the “My Afro Origins” digital platform. This portal was launched in July 2025 to streamline the process for applicants worldwide (myafroorigins.bj). The government charges a processing fee of 100 dollars for the initial certificate of eligibility. Applicants must provide proof of their ancestry. This proof can include DNA results from accredited labs or genealogical reports (myafroorigins.bj). The law acknowledges the difficulty of tracing lineages due to the “wall of slavery.” Therefore, it allows for authenticated oral testimonies and civil documents from territories of deportation.

Once approved, the applicant receives a certificate of nationality on a provisional basis. This certificate is valid for three years. To make the status permanent, the individual must visit Benin at least once during this period (myafroorigins.bj). This requirement ensures that the new nationals establish a physical connection with the land. It moves the program beyond a paper transaction and into a lived experience. Furthermore, it encourages “identity-based” tourism, which the government hopes will contribute significantly to the national economy (dailynewsegypt.com).

The African Union 6th Region Framework

Recognizing global descendants as a constitutive part of the continent. (au6rg.org)

Rights and Restrictions

It is important to distinguish between “nationality” and “political citizenship.” Under the 2024 law, nationality by recognition provides a Beninese passport and the right to live and work in the country (globalcit.eu). However, it does not automatically grant the right to vote. It also does not allow individuals to hold high-ranking civil service positions (citizenshiprightsafrica.org). These political rights typically require full naturalization, which involves a longer residency period.

For African Americans, the policy is designed to be inclusive. The Beninese government allows for dual nationality. This means that individuals do not have to renounce their United States citizenship to receive a Beninese passport (loc.gov). This is a critical detail for those who rely on social security or have established professional lives in America. The current administration under President Donald Trump has not restricted the acquisition of dual status for such cultural purposes. Maintaining both connections allows the diaspora to serve as a bridge between the two nations.

The quest for ancestry proof is a common hurdle for many applicants. Many families have shown great strength and resilience in preserving what little history they could. Benin’s law accepts a wide range of evidence to overcome this. For example, individuals born before 1944 in known deportation territories like Haiti or Brazil are often considered descendants by operation of law (myafroorigins.bj). This flexibility acknowledges the systemic destruction of African identities during the colonial era. The government is working to ensure that the “wall of slavery” does not prevent a return to the homeland.

Strategic Diplomacy and Economic Goals

Benin is positioning itself as a hub for the global African community. This initiative aligns with the African Union’s recognition of the diaspora as the “6th Region” of the continent (au6rg.org). By integrating the diaspora, Benin seeks to attract talent, investment, and specialized skills. The government aims to increase tourism’s contribution to the national economy to over 13 percent by 2030 (dailynewsegypt.com). Memorial sites and cultural festivals play a major role in this strategy.

The administration has recruited high-profile ambassadors to spread the word. Filmmaker Spike Lee and his wife, Tonya Lewis Lee, have championed the cause. In late 2025, American singer Ciara received her nationality in a televised ceremony in Cotonou (youtube.com, youtube.com). These figures help bridge the gap between French-speaking Benin and the English-speaking diaspora. The “My Afro Origins” platform is also available in multiple languages to reduce barriers for applicants from the United States and the Caribbean (myafroorigins.bj).

The 1999 apology by former President Mathieu Kérékou set the stage for these developments. He traveled to Baltimore to express regret for the role African kingdoms played in the slave trade (cipdh.gob.ar). This apology was a turning point. It shifted the national narrative from one of silence to one of accountability. Today, Benin views its citizenship policy as a form of practical reparation. It is an effort to heal deep historical wounds by welcoming the children of the continent back home.

The Path to Recognition

Challenges to Stability

While the citizenship program is a major success, Benin faces internal challenges. In December 2025, a small faction of the military attempted a coup against President Patrice Talon (beninwebtv.bj). The attempt was led by Lieutenant Colonel Pascal Tigri. However, the government quickly restored order with support from regional powers like Nigeria and ECOWAS. The coup plotters cited concerns over security in the north and democratic checks rather than opposition to diaspora laws (beninwebtv.bj).

Despite this brief period of instability, the diaspora initiatives remain a priority. The government continues to host major events like the “Vodun Days” festival in Ouidah. These celebrations attract thousands of visitors and showcase the spiritual heritage of the region. The persistence of these programs shows a deep institutional commitment. Even when political tensions rise, the mission of reconnecting with the diaspora serves as a unifying national goal.

The history of Reconstruction in the United States often failed to live up to its promises of full equality. In contrast, Benin is trying to build a legal foundation that cannot be easily dismantled. By codifying “nationality by recognition” into law, the state provides a permanent path for the diaspora. This legal certainty is vital for individuals who are considering investing their lives and resources into a new country.

A Vision for the Future

The push for diaspora citizenship is transforming the identity of Benin. It is no longer just a small West African nation. It is becoming a global center for Black heritage and memory. The International Museum of Memory and Slavery is currently under construction in Ouidah. This facility will anchor the “identity tourism” sector and provide a world-class space for education and reflection.

Education is also a key part of this transformation. Institutions like the University of Abomey-Calavi are exploring ways to integrate diaspora studies into their curricula. This effort parallels the civil rights movement in America, which fought for the inclusion of Black history in schools. By learning from each other, the continent and the diaspora can build a more complete understanding of their shared journey. This intellectual exchange is just as important as the legal citizenship itself.

Benin’s experiment with nationality by recognition is a model for other nations. Countries like Ghana and Sierra Leone have launched similar programs, but Benin’s legislative approach is particularly detailed. It addresses the practical needs of the diaspora while honoring the sacred nature of the return. As more individuals receive their passports, the “Door of No Return” is being renamed in the hearts of many. It is now a door of welcome, and it stands wide open for all who wish to walk through it.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.