Minnesota Poised to Pass Landmark Bill Addressing Racial Disparities in Child Welfare

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a continuous playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

The Minnesota legislature passed a groundbreaking bill. It aims to reduce the number of African American and minority children removed from their families. The Minnesota African American Family Preservation and Child Welfare Disproportionality Act now heads to Governor Tim Walz’s desk. People expect him to sign it into law (Minnesota Governor Expected To Sign Bill Raising Bar for Taking).

The Troubled History of Foster Care and Black Families in America

The modern foster care system in the United States has a complex and often discriminatory history. This is especially true in its treatment of Black children and families. Established in the 1800s to provide care for orphaned and homeless children, it has long operated with racial bias. Consequently, it disproportionately impacted communities of color (History of Foster Care | National Foster Parent Association).

Exclusion and Discrimination in Early Foster Care

In the early 20th century, formal child welfare institutions and white families largely excluded Black children from adoption. Instead, Black communities relied on extended family networks and churches to care for children in need. The foster care system did not allow greater participation by Black families until the latter half of the century (The Racial Origins of Foster Home Care | Du Bois Review).

“Already by the 1960s, many child welfare reformers began to suggest White foster families for Black youth under the presumption that more White families would be available,” writes Ellen Herman in The Racial Origins of Foster Home Care. “In effect, ‘Home’ became the biological family for White youth, whereas the foster home became a solution to Black child dependency” (The Racial Origins of Foster Home Care | Du Bois Review).

Overrepresentation of Black Children Persists Today

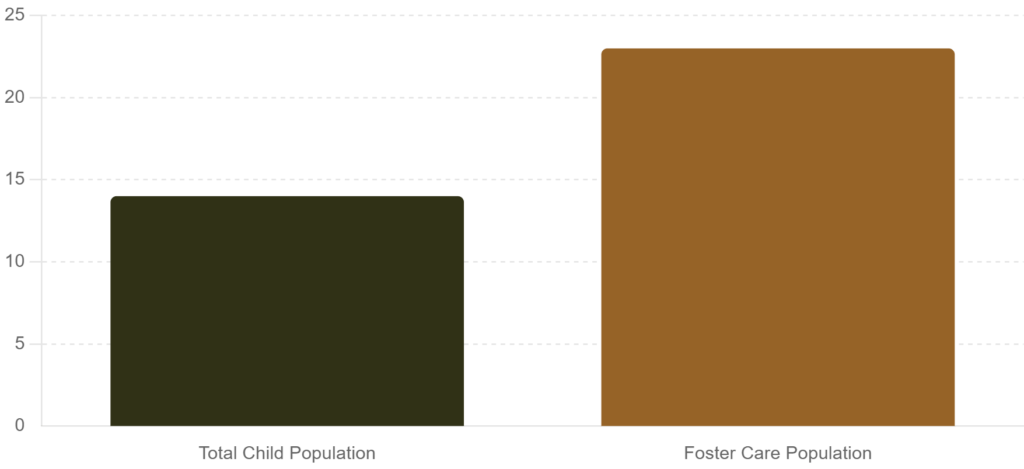

Black children and families gained greater access to the child welfare system over time. Nevertheless, significant racial disparities persist to this day. Black children make up a disproportionate representation in foster care compared to their share of the total child population. As of 2021, Black children made up 23% of foster youth despite being only 14% of all children in the U.S. (Race And Foster Care | Penny Lane Centers).

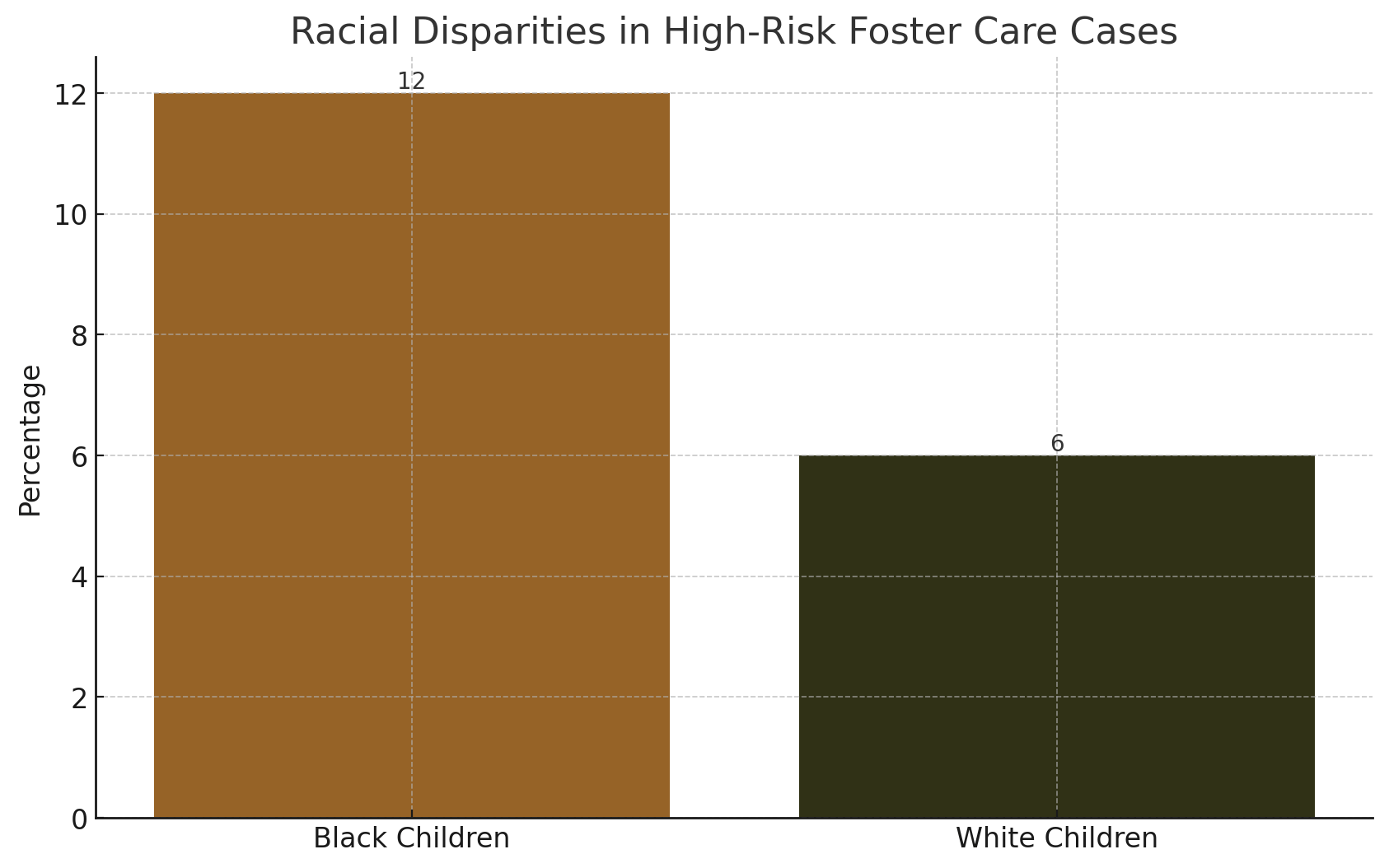

Studies consistently found that child protective services more often investigate and remove Black children from their families compared to white children. This discrepancy is not due to higher rates of abuse in Black families. Once in the system, Black children generally receive inferior services. Moreover, they remain in care longer, and reunite with their families less frequently. They also face higher rates of parental rights termination (Black Families Matter: How the Child Welfare System Punishes Poor).

A System Shaped by Racial Bias and Discrimination

Experts point to various factors behind the overrepresentation of Black children in foster care. These include higher rates of poverty and lack of support services. Most critically, they experience racial bias and discrimination at various points in the child welfare system. For instance, these points include reporting, investigations, and decision-making around removing children and terminating parental rights (There Are Too Many Black Children in Foster Care).

“Racial discrimination in the child welfare system is a human rights violation that we must talk about,” writes Kathleen Creamer of Community Legal Services of Philadelphia. “At every critical decision-making point in a child welfare case, research reflects that Black families experience worse outcomes than white families” (Racial Discrimination in Child Welfare Is a Human Rights Violation).

Distrust between Black communities and the child welfare system also contributes to disparities. This distrust stems from a long history of oppressive scrutiny and regulation of Black families. Consequently, Black parents are less likely to seek help voluntarily from the system (Black Families Matter: How the Child Welfare System Punishes Poor).

The Need for Systemic Reform

Advocates argue that addressing the stark and persistent racial disparities in foster care requires a multi-pronged approach. This approach includes tackling poverty and lack of services in Black communities. Additionally, it is essential to root out racial bias in the system, build trust, and reform child welfare policies. These reforms should prioritize family preservation and reunification over adoption and foster care placement.

The troubled history of foster care and Black families in America underscores the urgent need for systemic changes. These changes are essential to build a more equitable child welfare system that truly supports and strengthens all families.

Bill Requires “Active Efforts” to Keep Families Together

A key provision of the bill requires social services agencies to undertake “active efforts” to prevent out-of-home placements of African American, Hispanic, Native American, and mixed-race children. These groups are all overrepresented in Minnesota’s child welfare system compared to white children. These efforts include working to locate relatives or kin placements within 48 hours of a child’s removal (House passes new requirements meant to keep kids out of child).

“The purpose of this bill is to keep Black families in Minnesota intact when they first come into contact with child protective services,” said Rep. Esther Agbaje, the bill’s House sponsor (House passes new requirements meant to keep kids out of child).

Strict Limits on Terminating Parental Rights

The legislation also strictly limits when parental rights can be terminated for African American and disproportionately represented families. Termination is prohibited based solely on a parent’s failure to complete case plan requirements (House passes new requirements meant to keep kids out of child).

Addressing Racial Bias in Child Welfare System

Proponents argue the bill desperately needs to address racial bias and discrimination in Minnesota’s child welfare system. African American children in particular are removed from their families at highly disproportionate rates. This often happens for reasons of neglect and poverty rather than abuse (Bill to preserve Black families would now cover most MN foster kids).

In March, the Minneapolis NAACP filed a federal civil rights complaint. They allege that Minnesota’s child welfare system discriminates against Black children and families. Consequently, advocates argue child removals are traumatic and the current system is racially biased (Civil Rights Complaint Alleges Minnesota’s Child Welfare System).

Concerns About Funding and Safety

However, the bill faced challenges in previous legislative sessions. Some raised concerns about maintaining necessary safeguards for child safety (Bill to preserve Black families would now cover most MN foster kids).

Associations representing counties also said the law’s success hinges on the state providing increased funding for the child welfare workforce. This includes support services and training (Bill to preserve Black families would now cover most MN foster kids).

A National Model for Reform?

If signed into law as expected, the Minnesota African American Family Preservation Act would make the state one of the first in the nation to enact such stringent requirements. These requirements aim to avoid foster care placements and prioritize family reunification for African American and other disproportionately represented children.

Advocates hope Minnesota’s legislation will serve as a model for other states. They look to address stark and persistent racial disparities in the child welfare system. The bill passed the Minnesota House unanimously and received bipartisan support in the Senate. This points to growing acknowledgment across the political spectrum that bold reforms are needed.

About the author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He has authored several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.