“Exodusters,” Black Cowboys, and “Buffalo Soldiers:” African Americans on the Western Frontier

Exploring the journey of African Americans post-Civil War: From the struggles of the Jim Crow South to the opportunities and challenges of the Western Frontier. Discover the tales of Exodusters, Black cowboys, and Buffalo Soldiers.

After the Civil War, many African Americans hoped that the United States would reward their service during the conflict with emancipation and meaningful citizenship. However, by the end of Reconstruction in 1877, Southern legislatures denied voting rights to freedmen throughout the former confederacy. In addition, they faced discrimination in work and public life. Many Black Southerners turned instead toward radical politics as an alternative way to achieve equality. Others sought opportunities in the West, where they faced a new set of challenges. This article will explore the African American migration West where Black Americans found both opportunity and hardship on new lands in places like Nicodemus, Kansas. Additionally, Black cowboys found a living on the arduous Texas cattle drives. Still others sought acceptance through military service as “Buffalo Soldiers” during the Indian Wars against the indigenous people of the Western United States.

White Supremacy and Southern Redemption

In the post-Civil War era, Southern Whites sought a return to the racial status quo of the antebellum South in a process Southerners referred to as “Southern redemption.” The 15th Amendment granted voting rights to Black Americans. However, by the end of reconstruction, poll taxes, literacy tests, and the grandfather clause systematically denied Blacks the vote in the former Confederate states. Despite the 14th Amendment and its promise of citizenship and equal protection under the law, a series of laws known as Black codes subjected African Americans to arrest, imprisonment, and convict labor for the most trivial of offenses. By the turn of the 20th century, a rigid system of racial segregation that came to be known as “Jim Crow” relegated Blacks to separate and unequal schools and public accommodations. If that was not enough, white Southerners employed outright violence and terror to return Black people to a state of quasi-slavery.

In perhaps the most egregious example, on October 24, 1898, a mob of Southern whites attacked the Black community of Wilmington, North Carolina, killing at least 30 people and injuring many others. The riot resulted in the deaths of 22 Black people, with hundreds more forced to flee the city. During the incident, White supremacists violently overthrew Black and white elected officials. Historians believe the Wilmington massacre was the only violent coup of a local government in the history of the United States. Rev. Charles S. Morris provided a rare eyewitness account of the incident.

Nine Negroes massacred outright; a score wounded and hunted like partridges on the mountain; one man, brave enough to fight against such odds would be hailed as a hero anywhere else, was given the privilege of running the gauntlet up a broad Street, where he sank ankle deep in the sand, while crowds of men lined the sidewalks and riddled him with a pint of bullets as he ran bleeding past their doors; another Negro shot twenty times in the back as he scrambled empty handed over a fence; thousands of women and children fleeing in terror from their humble homes in the darkness of night …What caused all this bitterness, strife, arson, murder, revolution and anarchy at Wilmington? We hear the answer on all sides – “Negro domination.” I deny the charge. …The colored people comprise one-third of the population of the State of North Carolina; in the Legislature there are on hundred and twenty representatives, seven of whom are colored. There are fifty senators, two of whom are colored – Nine in all out of one hundred and seventy. Can nine Negroes dominate one hundred and sixty white men? (Taylor 2008, pp 174-175)

The “Exoduster” Movement

In the face of such violence, many Southern Blacks sought opportunities in the West. The 1862 Homestead Act provided a 160-acre plot of Western federal land free to those who would settle and farm it for at least five years. However, not all of those lands were open to Black settlers. Of the states that allowed Black homesteading, Kansas was the closest to the old Confederacy. Black migrants who came to be known as “Exodusters” seized upon this opportunity to escape the white supremacist regime of the post-Reconstruction South.

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a former slave born in Nashville, Tennessee, became a leader of the “Exoduster Movement.” In later years he became known as the “Father of the Exodus.” By 1874, Singleton and his associates formed the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association in Tennessee, which steered more than 20,000 Black migrants to Kansas between 1877 and 1879. (loc.gov)

In 1878, Benjamin Singleton himself led a party of 200 settlers to Kansas. During the 1870s and early 1880s, twenty-five thousand Black migrants sought refuge in Kansas with the hopes of establishing a plot of land in their own Black towns free from the tyranny of the Jim Crow South. (Taylor 1998, p. 136)

Nicodemus, Kansas was the best-known of these Black communities in the western territories. However, despite the free land, Black migration across the Mississippi River was no small task, and life on the frontier was a hard living. “The first settlers had little farm equipment and faced drought, prairie fires, crop failures, and grasshopper swarms.” (Taylor 1998, p. 139)

Willianna Hickman was one of the first settlers to reach Nicodemus on the western plains of Kansas. She traveled with 140 other colonists on a trip that began March 3, 1878, and left the following account of her journey:

We left… For Nicodemus, traveling overland with horses and wagon. We were two days on the way, with no road to direct us save the deer trails and Buffalo wallows. We traveled by compass. At night the men built bonfires and sat around them, firing guns to keep the wild animals from coming near. …When we got in sight of Nicodemus the men shouted, “There is Nicodemus.” Being very sick I hailed this news with gladness. I looked with all the eyes I had. I said, “Where is Nicodemus? I don’t see it.” My husband pointed out various smokes coming out of the ground and said, “That is Nicodemus.” The families lived in dugouts. The scenery to me was not all inviting and I began to cry. (Taylor 2008, p 151)

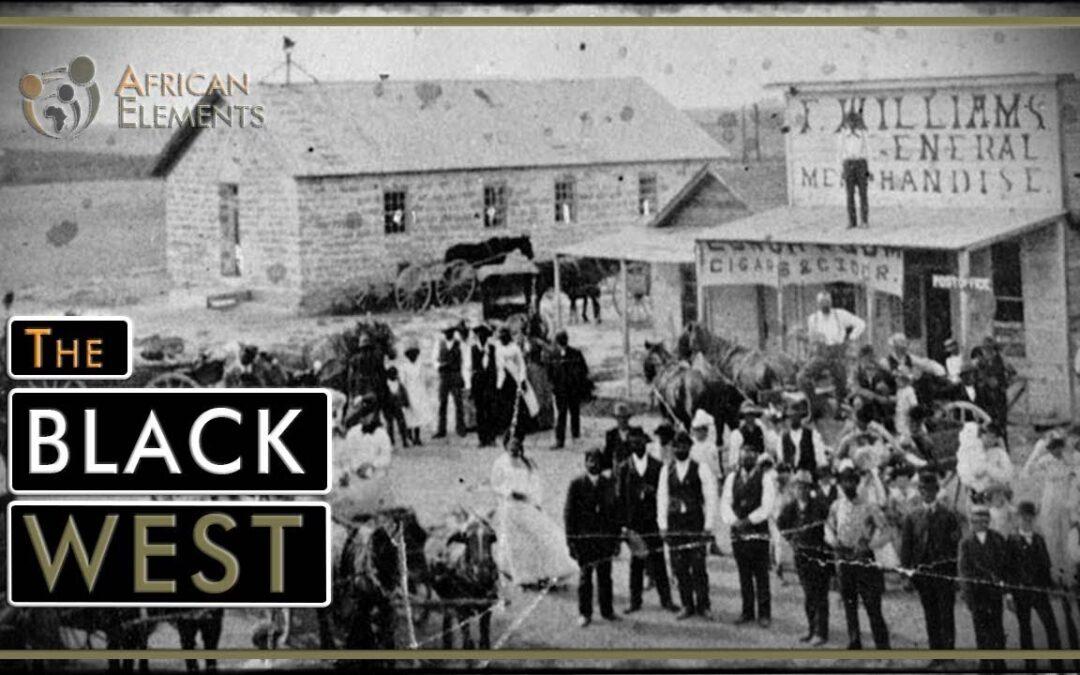

However, by the mid-1880s, Nicodemus was a thriving community with many farms and businesses complete with its own newspaper and schoolhouse, along with Baptist, Free Methodist, and African Methodist Episcopal churches. However, its success was short-lived because the region’s climate did not prove reliable for long-term community sustainability. Nicodemus was doomed when the Missouri Pacific, the Santa Fe, and the Union Pacific railroads bypassed the town. The town fell into steady decline by the end of the 1880s. Ultimately Nicodemus could not survive without some connection to the larger Western infrastructure.

Despite the hardships, the opportunity for self-determination on the frontier during the post-Reconstruction period appealed to many African American migrants when stacked against the ordeal of mob violence in the Jim Crow South. According to historian Quintard Taylor, when a reporter for the St. Louis Globe asked a woman if she would return to the South, she replied, “What, go back! … I’d sooner starve here.” (Taylor 1998, p. 141)

Black Cowboys

With racism firmly entrenched in both Southern and Northern cities, many Blacks looked to the Western frontier. Work in the cattle industry of the Southwest was one alternative to sharecropping or the prison chain gang. As a result, at least 5000 Blacks were known to have worked as cowboys in the West. They comprised about 2% of the total stock raisers, herders, and drovers in 1890. (Taylor 1998, p. 158) However, the work was difficult. In his book, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 historian, Quintard Taylor uncovered the narrative of Daniel Webster Wallace who described his experience on the cattle drive,

where everyone “slept on the ground in all kinds of weather with our blankets for a bed … a saddle for a pillow … and gun under his head.” He recalled standing guard on stormy nights “when you couldn’t see what you were guarding until a flash of lightning,” or where a rattlesnake might be “rolled up in your bedding” or where cowboys were awakened by the “howl of the wolf or holler of the panther.” (Taylor 1998, p. 159)

Demanding as the life of a cowboy was, it took place in relatively free albeit sometimes lawless terrain. However, it was often the case that the absence of law was preferable to Jim Crow law. In fact, at the end of the cattle drive from the Texas Panhandle to Dodge City, Kansas, Black and white drovers shared hotel rooms and gambling saloons. One hotel clerk illustrated the relative freedom that accompanied “frontier law” when he

told a black cowboy that no rooms were available, the drover drew what the frightened clerk described as the “longest barreled six-shooter he had ever seen” and waved it in his face, saying, “You’re a liar!” The clerk quickly rechecked his roster and found a suitable room. (Taylor 1998, pp. 160-161)

The Buffalo Soldiers

Whereas Benjamin Singleton and the communities of African American migrants sought self-determination through mass migration, others headed to the western frontier for entirely different reasons. As soldiers in the United States Army, the Buffalo Soldiers were the African American servicemen who enlisted in the United States Army during the latter half of the nineteenth century. They represent one instance in which Black and Native American history became paradoxically entangled. Success and opportunity for African Americans came at the expense of the indigenous people and encroachment on native lands. As historian, Gerald Horne notes,

African Americans everywhere should look upon this time in their history with extreme caution. Many American Indian men, women and children were mercilessly slaughtered by these Buffalo Soldiers who were led by white officers. . . .This is not one of the prouder moments for African Americans.

However, it is important to view their actions in context. The Buffalo Soldiers consisted of freed slaves, former sharecroppers, and political refugees with limited options.

The Army Reorganization Act of 1869 reassigned Black soldiers who served during the Civil War to four all-Black regiments – the 9th and 10th cavalry and the 24th and 25th infantry. The two Black infantry regiments comprised 10 percent of the Army’s infantry, while the 9th and 10th cavalry represented 20 percent of the cavalry regiments. (Schubert 4-5)

According to Historian Thomas Philips, Black soldiers participated in 141 of 2,704 engagements with indigenous tribes during this era. (Schubert 164-165) They were sent into the heart of the Indian wars that continued through the turn of the 20th century. Stationed in “desolate posts, issued shoddy equipment, worn-out horses and rations of black coffee and bad meat.” The United States Army pitted the Buffalo Soldiers against various indigenous groups who waged a war of resistance against the encroaching settlers. However, with a regular pay of $13 a month, even these conditions were an attractive alternative to a life of perpetual debt that Southern Black sharecroppers experienced.

The Buffalo Soldiers served at a time when notions of manifest destiny drove U.S. expansion westward. Manifest Destiny was the belief that the United States had an inherent right to expand westward across North America and that this expansion was ordained by God. It was rooted in the notion that Native Americans represented an inferior and uncivilized culture and that it was God’s will that they be conquered and uplifted through Anglo civilization. In other words, it was rooted in white supremacy.

In addition to escaping dire poverty in the South, Black Soldiers who were subject to white supremacy hoped that service to their country would earn them white acceptance. Whatever one may think of the decisions they made, Exodusters, Black cowboys, and Buffalo Soldiers faced tough choices under unimaginably difficult circumstances. What would you do?

SOURCES

Schubert, Frank N. (1997). Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870-1898. Scholarly Resources Inc. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-8420-2586-7.

Taylor, Quintard. From Timbuktu to Katrina: Readings in African-American History. Boston, Mass: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008. Print.

Taylor, Quintard. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998)

Weekly, Harpers, et al. “The African-American Mosaic Western Migration.” Library of Congress, 23 July 2010, www.loc.gov/exhibits/african/afam009.html.