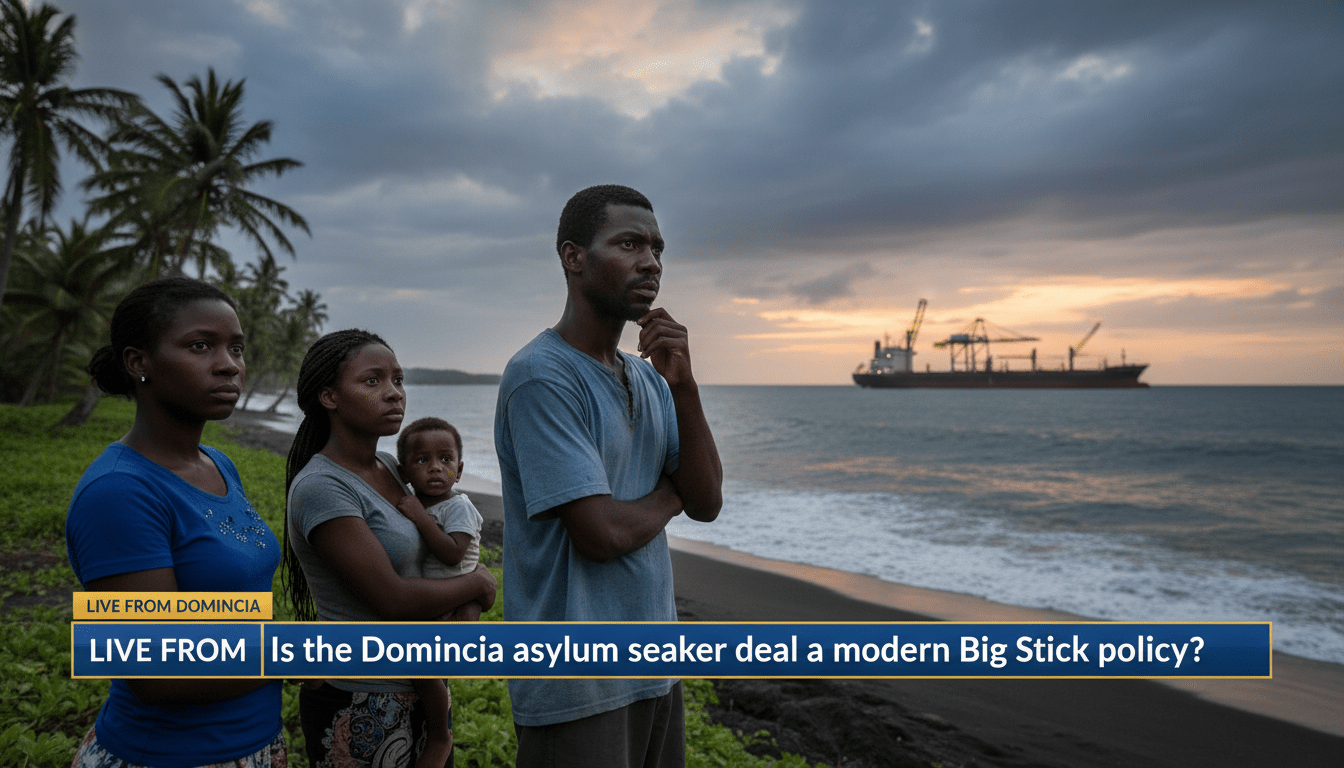

Is the Dominica asylum seeker deal a modern Big Stick policy?

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

The New Frontier of Border Control

In early 2026, the Commonwealth of Dominica signed a historic agreement with the United States. This small Caribbean nation agreed to host asylum seekers in a third-country arrangement. The deal aims to share the responsibility for global refugees. However, many residents of the island feel a sense of deep alarm. They worry about the capacity of their small country to handle new arrivals (miamiherald.com).

This arrangement is part of a strategy known as externalizing borders. Wealthy nations often shift border enforcement to smaller, less wealthy countries. This practice moves the migrant crisis away from the actual borders of the destination nation. For the United States, this means creating a security perimeter far from its shores (immigrantjustice.org). The current administration under President Donald Trump continues to push for these offshore solutions. This policy places immense pressure on states like Dominica that rely on U.S. cooperation (miamiherald.com).

Externalization often prevents migrants from reaching territories with high legal protections. When asylum seekers stay in third countries, they lose access to certain judicial rights. This creates a legal limbo for those seeking safety. Many scholars compare these zones to historical precedents like Guantánamo Bay. These areas often lack the oversight found within the United States (immigrantjustice.org). Many people in the Black diaspora see these tactics as a way to isolate vulnerable groups. This historical pattern often targets Black migration and limits the movement of people from the Global South.

The Demographic Fragility of Dominica

Source: World Bank & IOM Data (worldbank.org, iom.int)

The Roots of Offshoring

The practice of processing migrants offshore is not a new idea. It began in the early 1990s during the George H.W. Bush administration. The U.S. Coast Guard intercepted Haitian refugees at sea. Officials held these individuals at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base (wikipedia.org). The Clinton administration expanded this practice to include Cuban migrants. Because the base was not U.S. soil, the government argued that migrants had no constitutional rights (immigrantjustice.org).

Another major step happened in 2002 with Canada. The Safe Third Country Agreement required asylum seekers to apply for protection in the first safe nation they reached. This logic allows wealthy nations to return migrants to transit countries (immigrantjustice.org). The Trump administration used this framework to create Asylum Cooperative Agreements in 2019. These deals involved Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (americanimmigrationcouncil.org). These nations were forced to accept migrants from other countries instead of letting them enter the United States.

The 2026 deal with Dominica is the latest chapter in this history. It utilizes administrative leverage to compel cooperation from small islands. The U.S. government now uses visa restrictions as a primary tool. For example, the U.S. imposed travel restrictions on Dominica in late 2025. This move targeted the island’s citizenship programs (miamiherald.com). Facing economic isolation, Dominica officials felt they had few options. They chose to accept the asylum deal to protect travel rights for their citizens.

The Price of Citizenship and Sovereignty

Dominica relies heavily on its Citizenship by Investment or CBI program. This program allows foreign nationals to purchase a “golden passport” for a large fee. These fees are a vital economic lifeline for the island. In recent years, CBI revenue accounted for over half of the national revenue (timescaribbeanonline.com). However, the United States views these programs as a significant security risk. Officials worry that these passports allow individuals to bypass global vetting (miamiherald.com).

The U.S. Department of State expressed concerns about “woeful inadequacies” in vetting. They suggested that individuals could hide their true identities through these passports. This led to the introduction of Visa Bonds for travelers from Dominica. These bonds can cost as much as $15,000 per person (miamiherald.com). For a resident of a developing nation, this amount is often higher than a yearly income. Such a high cost functions as a barrier to legal protections and travel.

Critics argue that these bonds are a form of financial coercion. They penalize the entire population for the policies of their government. The bonds make it nearly impossible for many to visit family in the United States. This situation creates a steep financial barrier for the Black diaspora. Many families cannot afford the upfront capital required for a simple visit (whitehouse.gov). This policy targets majority-Black nations with high overstay rates. It signals a move toward a migration system that favors the wealthy.

Financial Barrier: The Visa Bond vs. Income

The Visa Bond creates a prohibitive wall for average citizens. (miamiherald.com, whitehouse.gov)

A Nation in Recovery

Dominica is still healing from the destruction of Hurricane Maria in 2017. This Category 5 storm caused damage worth 226 percent of the nation’s GDP. It destroyed nearly a quarter of the entire housing stock on the island (worldbank.org). Thousands of people still live in temporary or precarious conditions today. The island faces a constant struggle to rebuild its infrastructure and economy (reliefweb.int).

Public systems like healthcare and education are already under great strain. Dominica spends about 3.9 percent of its GDP on health. It also spends roughly 3.4 percent on education (imf.org). Adding thousands of refugees would place a heavy burden on these services. Residents ask who will pay for the housing and schooling of the newcomers (miamiherald.com). The government has not fully explained where the funding will come from for long-term care.

The capacity of the island is physically limited. With only 72,000 residents, a small influx of migrants is a huge change. International migrants already made up over 11 percent of the population in 2020 (iom.int). The opposition party warns that the island lacks the space for a massive population shift. They argue that the government has not been transparent about the numbers. The lack of clear information has fueled local fears about national stability (timescaribbeanonline.com).

The Echoes of the Big Stick

The deal reflects a long history of U.S. intervention in the Caribbean. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt introduced the Roosevelt Corollary. He claimed the U.S. had the right to act as an “international police power” in the region (wikipedia.org). This policy turned the Caribbean into what many called an “American Lake.” The U.S. often intervened to stabilize economies and protect its own interests (studysmarter.co.uk).

Historically, the U.S. used military force to ensure Caribbean cooperation. For instance, the U.S. invaded the Dominican Republic in 1965 to maintain regional stability (miamiherald.com). Today, the methods have changed, but the pressure remains. Administrative leverage has replaced military invasions in many cases. The U.S. now uses visa access and economic sanctions to dictate policy. This “modern Big Stick” diplomacy forces small states to act as buffer zones for American migration issues (immigrantjustice.org).

Social justice advocates see this as a form of neo-colonialism. It allows the U.S. to push its problems onto Black and Brown nations. These smaller countries often lack the resources to handle the complex needs of refugees. This practice mirrors historical patterns where exclusionary tactics were used against marginalized groups. By forcing Dominica to host asylum seekers, the U.S. avoids its own legal obligations. It shifts the human and financial cost of migration to a nation already in crisis (immigrantjustice.org).

Economic Impact: Hurricane Maria Damage

The Hidden Face of the Asylum Seekers

The identities of the asylum seekers remain a subject of debate. Official documents often use broad terms like “global refugees.” However, data shows that many migrants in the region come from specific areas. These include Haiti, Venezuela, and parts of West Africa (iom.int). Many individuals from Senegal and Nigeria now use the Caribbean as a transit point. They hope to reach the United States or South America for a better life.

Dominica’s Prime Minister stated the deal is for those who cannot return home. This often applies to people from conflict zones or those who are stateless. For example, refugees from Sudan or other war-torn areas often fall into this category (antigua.news). The opposition party has criticized the lack of detail on these individuals. They want to know the specific nationalities and backgrounds of those arriving. This lack of transparency leads to rumors and social tension on the island (timescaribbeanonline.com).

Officials from the U.S. and Dominica promise strict vetting for all arrivals. They aim to screen for violent individuals and security risks (miamiherald.com). However, historical vetting has often been a tool for exclusion. In the past, security screenings were used to target Black migrants specifically. These screenings sometimes viewed cultural differences as a threat to national loyalty (africanleadershipmagazine.co.uk). This history makes many people skeptical of the current vetting process. They worry it might be used to label vulnerable people as threats.

Impact on the Global Black Diaspora

The deal and the visa bonds threaten deep family ties. The diaspora of Dominica is larger than the island’s current population. About 78,200 Dominicans live abroad, mostly in the U.S. and the U.K. (iom.int). These individuals provide critical support through remittances. They also manage family properties and affairs from a distance. The new travel barriers make these connections much harder to maintain.

Family visits for weddings or funerals are becoming too expensive. Students and young professionals are being priced out of travel. This limits the upward mobility of the next generation of the diaspora. Such policies isolate the island from its global community. This financial barrier disproportionately affects people from majority-Black nations (whitehouse.gov). It is a form of economic justice barrier that prevents family reunification.

Furthermore, these deals create zones with fewer legal rights. Migrants moved to third countries lose access to U.S. courts. They often have no right to legal counsel or the chance to appeal. This situation places them at risk of indefinite detention in a country with few resources (immigrantjustice.org). The Receiving country may not have the legal infrastructure to protect them. This weakens the international principle of protecting refugees from danger.

The Future of Sovereignty

Dominica is currently facing a fiscal crisis with high public debt. The national debt has reached roughly 100 percent of its GDP in recent years (imf.org). This leaves very little money for new logistical burdens. The IMF has warned that the island struggles to maintain its own basic services. Adding the responsibility of hosting asylum seekers seems like an impossible task for some (timescaribbeanonline.com).

Political tension on the island is also rising. Opposition leaders accuse the government of making “secret deals” with the U.S. They believe the nation’s security is being traded for travel rights. Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit called the deal a necessary compromise. He argued it was the only way to safeguard his people’s ability to travel (miamiherald.com). This highlights the difficult position of small Caribbean states in the modern world.

The U.S.–Dominica deal is a significant shift in how migration is managed. It shows how vetting and visa access are used as diplomatic weapons. For the residents of Dominica, it is a reminder of their vulnerability. They are caught between economic needs and the demands of a superpower. The history of U.S. intervention is being rewritten through “shared responsibility.” Many people remain unsure if this path will lead to stability or more crisis (immigrantjustice.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.