Sudan’s Deep Scars: The Hidden Roots of West Darfur Attacks

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

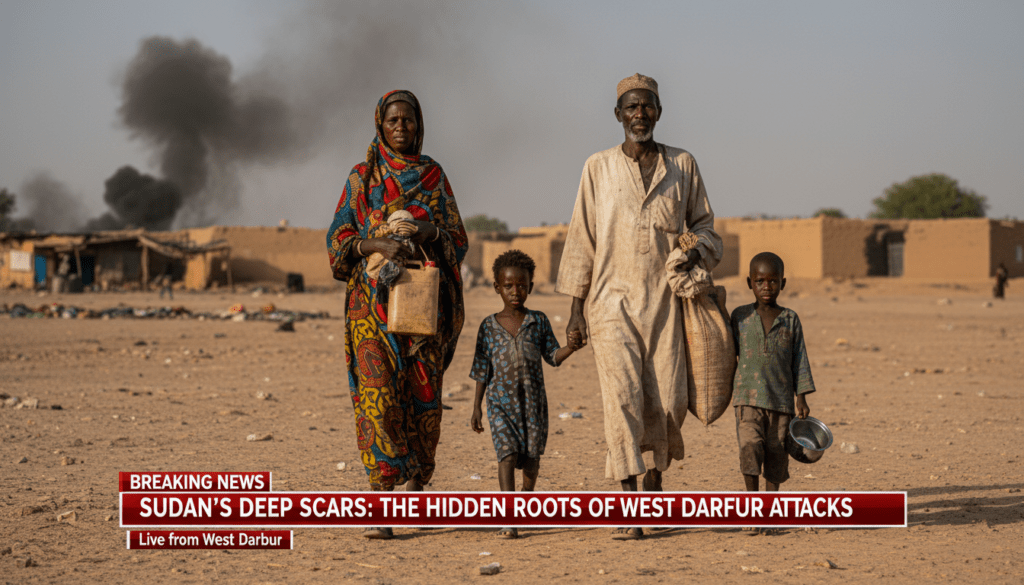

The news from Sudan is heavy. In early January 2026, reports emerged that another wave of violence swept through West Darfur. At least 114 people were killed across several villages in just one week. Families had to flee their homes quickly as fear moved through the region like a storm. This violence is part of a much older story. To understand why people are dying today, one must look at the history behind the headlines (hrw.org, arabnews.jp).

Sudan is currently a nation divided. A brutal civil war began in April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces and a paramilitary group called the Rapid Support Forces. As of 2026, the country is split in two. The regular army controls the north and east. Meanwhile, the paramilitary forces have seized control of the five state capitals in Darfur. This has turned the region into a dark hole where information and help are hard to find (csf-sudan.org, pbs.org).

Source: Verified Data synthesis 2026

The Legacy of the Masalit Sultanate

The land of West Darfur has a proud history. For centuries, it was known as Dar Masalit. This was the seat of the Masalit Sultanate between 1884 and 1921. The Masalit people are sedentary farmers. They have a long history of protecting their independence. In the past, they fought off the British, the French, and other local kingdoms. This history created a strong bond between the people and their land (britannica.com, britannica.com).

This deep connection to the land is the reason why current attacks are so painful. When families are forced to flee, they are losing more than just a house. They are losing a piece of their identity that dates back hundreds of years. The resilience of these African American families and their ancestors in the diaspora often mirrors this struggle to keep kinship ties strong even during forced movements (nobelpeacecenter.org, wikipedia.org).

The Masalit leadership was once very powerful. However, modern governments in Sudan tried to change this. They wanted to control the land for their own political gain. They used the law to weaken the traditional rulers. This created a situation where different groups began to fight over who truly owned the soil. These disputes over land rights are a major reason why the “tribal” violence reported today is actually a political battle (hrw.org, sudanembassy.nl).

Drought and the Breakdown of Tradition

Environment and climate also played a role in this tragedy. A massive drought hit the region between 1983 and 1985. This was known as the Great Sahelian Drought. It forced nomadic groups from the north to move south. These groups were mostly Arab pastoralists who raised animals. They needed water and grass for their livestock. They moved into the lands traditionally managed by the Masalit and Fur farmers (researchgate.net, merip.org).

In the past, these groups had agreements. Farmers allowed herders to pass through their land after the harvest. In exchange, the animals fertilized the soil. This was part of a traditional land system called Hakura. However, the drought was so bad that these old agreements broke down. The groups began to clash over the few resources that remained. This was the start of the modern ethnic friction in Darfur (genocidewatch.com, britannica.com).

The government in the capital city of Khartoum did not try to fix these problems fairly. Instead, they took sides. They used the conflict to their advantage. By supporting certain groups over others, the state turned neighbors against one another. This meddling ensured that local leaders remained divided. Therefore, they could not unite against the central government (wilsoncenter.org, liberationorg.co.uk).

Political Games and the 1994 Shift

In 1994, the regime of Omar al-Bashir made a major change. They reorganized the administration of West Darfur. They carved up the traditional “Dar Masalit” territory. The government gave official leadership titles to Arab groups on land that belonged to the Masalit. This was a direct attack on the Masalit Sultanate legacy. It politicized ethnic identity to create a loyal base for the government (hrw.org, hrw.org).

This shift made it hard for groups to live together. When the government gives one group power over another’s ancestral home, violence usually follows. This was not a simple mistake. It was a strategy. The state wanted to ensure that people were more loyal to their ethnic group than to the nation. This made it easier for the regime to stay in power by using “divide and rule” tactics. These policies are part of a larger history of Black voter disenfranchisement and political exclusion seen in many parts of the world (aa.com.tr, arabcenterdc.org).

The 1994 changes were a turning point. They moved the conflict from local resource disputes to a fight for political survival. Non-Arab groups felt that the state was trying to erase them. They felt like “guests” in their own home. This feeling of being marginalized led to the uprising in 2003. When people have no political voice, they sometimes feel they have no choice but to resist (hrw.org, wikipedia.org).

The Birth of the Janjaweed and the 2003 Genocide

In 2003, two rebel groups rose up against the Sudanese government. These were the Sudan Liberation Movement and the Justice and Equality Movement. They were made up of non-Arab ethnic groups like the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa. They were tired of being ignored by Khartoum. They wanted a fair share of the nation’s wealth and a say in how they were governed (wikipedia.org, au.int).

The government responded with extreme force. Instead of using only the regular army, they armed local Arab militias. These militias were known as the Janjaweed. They carried out a scorched-earth campaign across Darfur. They burned villages, killed civilians, and used sexual violence as a weapon. Between 2003 and 2005, around 300,000 people died. The United States and other nations called this a genocide (genocidewatch.com, wilsoncenter.org).

The Janjaweed were not just random bandits. They were supported by the state. They were given weapons, communication gear, and a promise that they would not be punished. This created a cycle of impunity. The leaders of these militias learned that they could commit terrible crimes and get away with them. This legacy of resistance against systematic oppression is a common theme for those who have been marginalized by powerful states (hrw.org, hrw.org).

From Militias to the Rapid Support Forces

The Janjaweed did not go away after the genocide. In 2013, the government formalized these militias. They became the Rapid Support Forces. They were led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti. He rose from being a militia leader to a powerful military commander. The government used the RSF to fight rebels in other parts of the country and to control the gold mines in Darfur (hrw.org, csf-sudan.org).

Hemedti became very wealthy and powerful. His forces were often better equipped than the regular army. This created a “state within a state.” By 2023, the tension between Hemedti and the leader of the regular army, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, reached a breaking point. They could not agree on how to merge their two armies. On April 15, 2023, this power struggle turned into a full-scale war in the streets of Khartoum (liberationorg.co.uk, arabcenterdc.org).

The RSF used the same tactics in 2023 that the Janjaweed used in 2003. They returned to West Darfur and targeted the Masalit people once again. In the city of El Geneina, thousands were killed as they tried to flee to Chad. Human Rights Watch reported that this was a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing. The goal was to remove non-Arab populations from the land forever (hrw.org, hrw.org).

The Horror of January 2026

The violence in early 2026 shows that the war is far from over. In just one week, at least 114 civilians were killed in West Darfur. In the town of Kernoi, near the northern border, RSF attacks killed 63 people. These attacks targeted the Zaghawa and Masalit communities. Witnesses say the fighters burned houses and destroyed the local market to make sure people could not return (hrw.org, arabnews.jp).

The regular army also contributed to the death toll. In North Darfur, the SAF launched drone strikes on the town of Al-Zuruq. This town is a known stronghold for Hemedti’s relatives. The strikes hit a busy market and killed 51 people. Many of the dead were members of the Dagalo family. This shows how the war has become a personal feud between leaders, with civilians caught in the middle (csf-sudan.org, pbs.org).

These attacks are part of a larger pattern. The RSF now controls almost all of Darfur. They are using their power to settle old scores and take control of resources. Meanwhile, the international community has struggled to stop the fighting. President Donald Trump and other world leaders have called for peace. However, the flow of weapons into the country from outside powers has made it hard to reach an agreement (au.int, liberationorg.co.uk).

(Supplies/Funds)

(Strategic Ties)

Regional proxies turn a local struggle into a global battlefield.

Global Anti-Blackness and the African Diaspora

For the African Diaspora, the crisis in Sudan is a major social justice issue. It highlights a painful reality of global anti-blackness. The media often focuses on wars in Europe while remaining relatively silent on the “Land of the Blacks.” This lack of attention allows the violence to continue without enough global pressure to stop it. It is a reminder of how certain lives are valued more than others in the global eye (aa.com.tr, pbs.org).

The conflict also involves a racialized hierarchy. In Sudan, the “Arab” and “Non-Arab” identities are complicated. They are not always about skin color, as many people look similar. Instead, they are about lineage, language, and power. The state has historically prioritized those who claim Arab identity. This has marginalized those who identify with their indigenous African roots. This system of hierarchy is something that many in the diaspora recognize from their own histories of medical experimentation and systemic neglect (wikipedia.org, merip.org).

Sudan is the site of ancient civilizations like Nubia and Kush. The destruction of its culture and people is a loss for all humanity. Diaspora communities are now using digital advocacy to raise awareness. They are supporting “Mutual Aid” groups on the ground. These are local networks run by regular people who provide food and medicine when big organizations cannot get through. This spirit of community survival is a powerful tool against state violence (nobelpeacecenter.org, au.int).

Conclusion: A Call for Justice

The attacks in West Darfur in January 2026 are a tragedy. However, they are not a surprise. They are the result of a century of land disputes, political manipulation, and a failure to hold killers accountable. The 114 people who died in the past week are victims of a system that has long devalued their lives. To stop the cycle, the world must address the root causes of the war (hrw.org, liberationorg.co.uk).

Justice is the only way to find a lasting peace. This means enforcing arrest warrants from the International Criminal Court. It means stopping the flow of weapons from regional powers. Finally, it means listening to the people of Darfur who want to return to their ancestral lands. The history behind the headlines shows that without land rights and political voices, the violence will only continue. Support for grassroots responders is a vital step toward a better future (wilsoncenter.org, pbs.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.