Uganda’s 2026 Election: Why the Digital Blackout Matters

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

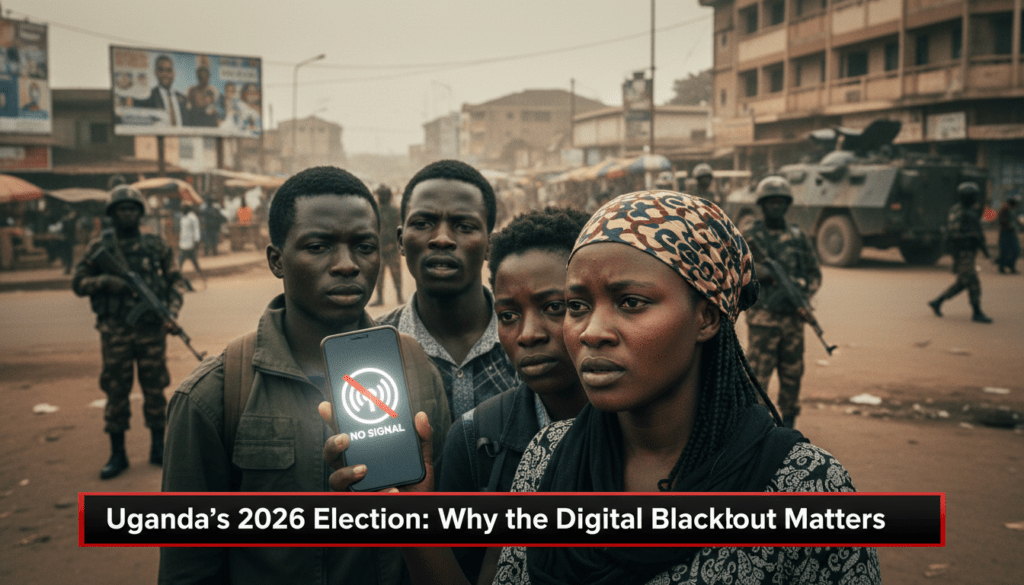

The streets of Kampala are quiet but the air feels heavy with tension. Soldiers in camouflage gear stand at every major intersection while military vehicles patrol the dusty roads. This sight has become a familiar part of the landscape during election season in Uganda. On January 13, 2026, the nation went dark in a different way. The government ordered a total internet blackout just as citizens prepared to cast their votes (observer.ug). This move disconnected over ten million users from the world in less than thirty minutes (citynews.ca). Many people believe this silence is a tool used to stop the public from organizing or speaking out against the ruling party.

The current situation is part of a much longer story of power and control. President Yoweri Museveni has led the country since 1986. He once promised that his government would bring a fundamental change to the nation (observer.ug). In the early years, leaders in the West saw him as a reformer who could bring democracy to East Africa. However, the headlines today tell a different story of suppressed votes and digital walls. To understand why the internet goes dark, one must look at how the government has changed its tactics over the last four decades. The struggle for the ballot in Uganda shares a troubling history of disenfranchisement seen in other parts of the world.

Voter Growth vs. Digital Control

The Long Road from Liberation to Longevity

Yoweri Museveni came to power after a five-year guerrilla conflict known as the Bush War. His National Resistance Army fought against regimes they claimed were oppressive and undemocratic (theeastafrican.co.ke). When he took the oath of office, he argued that the problem of Africa was leaders who stayed in power too long. This message resonated with a population that had survived years of chaos and violence. For a while, Uganda experienced economic growth and improvements in public health. The government was praised for its efforts to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic during the 1990s (observer.ug).

As the years passed, the focus shifted from national liberation to maintaining the presidency. In 2005, the Ugandan Parliament voted to remove the two-term limit for the president (observer.ug). This change allowed Museveni to run for a third term and beyond. Later, in 2017, the government removed the age limit of 75 for presidential candidates. This move was controversial and led to brawls inside the parliament building. Opposition members were physically removed by security forces during the debate (observer.ug). These legal changes cleared the path for a leader to rule indefinitely, which many activists argue undermines the spirit of democracy.

From Paper Bans to Digital Kill Switches

Censorship in Uganda has evolved alongside technology. During the 1970s, previous regimes used direct violence and banned printed magazines to silence critics. Under the current administration, the press was initially more open. However, independent outlets like the Daily Monitor began to face harassment in the late 1980s (observer.ug). Journalists were arrested, and offices were sometimes raided by police. As the internet became the primary tool for communication, the state moved its focus to the digital world. The government now views social media as a threat to national security rather than a tool for progress.

The “kill switch” is the most powerful weapon in the government’s digital arsenal. This refers to a direct order given to internet service providers to shut down all gateway traffic. In 2026, the Uganda Communications Commission forced companies to comply or face the loss of their licenses (citynews.ca). By cutting the connection, the state prevents the real-time reporting of human rights abuses or ballot stuffing. This tactic makes it nearly impossible for the opposition to coordinate their polling agents in rural areas. It also stops the flow of information to the international community during the most critical hours of the vote.

The 2021 Election as a Strategic Blueprint

The 2021 election cycle provided the template for the current crackdown. During that time, a popular musician named Robert Kyagulanyi, known as Bobi Wine, emerged as a major challenger. His message of “People Power” reached a large audience of young people who felt ignored by the political elite (tpr.org). Since over 75 percent of the Ugandan population is under the age of 30, this demographic shift posed a serious threat to the ruling party. The government responded with a massive show of force. In November 2020, security forces killed at least 54 people during protests following the arrest of Bobi Wine (hrw.org).

On the eve of the 2021 vote, the government implemented its first total internet blackout. They claimed this was necessary to prevent foreign interference and misinformation (observer.ug). This happened after Facebook removed several pro-government accounts for using fake profiles to manipulate public debate (observer.ug). However, observers argued the real goal was to hide state-led violence. Bobi Wine was placed under house arrest for eleven days immediately after the election. The blackout prevented his team from using digital tools to tally the results independently. This sequence of events showed that the state was willing to sacrifice the digital economy to maintain political control.

The Economic Cost of National Silence

Shutting down the internet does more than stop social media posts. In Uganda, the digital infrastructure is the backbone of the national economy. Mobile money services are essential for daily life for millions of people. Unlike in some Western nations, mobile money is the primary way citizens pay for utilities, school fees, and food (observer.ug). When the internet goes dark, the unbanked majority loses access to their liquid capital. This creates a secondary crisis where families cannot buy medicine or basic necessities. Small businesses that rely on digital transactions face immediate and heavy losses.

The financial impact of these blackouts is staggering. During the 2021 election, the economy lost an estimated 109 million dollars over five days (observer.ug). With more people online in 2026, the projected losses are even higher. The informal sector, which makes up a huge part of the economy, suffers the most. Rural populations who live far from physical bank branches are essentially cut off from the financial system. The government views these costs as a necessary trade-off for security. This approach demonstrates how political survival is often prioritized over the economic well-being of the citizens fighting for representation in their own country.

ESTIMATED LOSS: $20M+ PER DAY DURING SHUTDOWN

Digital Authoritarianism and Surveillance

Digital authoritarianism is the use of technology to track, intimidate, and silence citizens. It mirrors the old tactics of secret police but uses modern tools like facial recognition and AI. In Uganda, the government has invested heavily in surveillance cameras and social media monitoring (hrw.org). These tools are used to identify political dissidents and activists. Laws like the Computer Misuse Act are frequently used to arrest people for online comments that the state considers offensive (observer.ug). This creates a chilling effect where people are afraid to share their opinions online for fear of being tracked down by security forces.

Activists such as Sarah Bireete have faced constant pressure from the state. Bireete, who leads a constitutional governance group, was arrested in late 2025 during a crackdown on civil society (observer.ug). Many NGOs have seen their bank accounts frozen or their offices closed by the government. The goal of these actions is to dismantle the support systems that allow citizens to organize. By controlling both the physical streets and the digital space, the ruling party seeks to eliminate any platform for dissent. This level of control has historically impacted global politics by setting a precedent for other regimes to follow.

The Rise of General Muhoozi and Succession Fears

A new factor in the 2026 election is the political rise of General Muhoozi Kainerugaba. He is the son of President Museveni and was recently promoted to lead the Ugandan military (observer.ug). Muhoozi has been very active on social media and has formed his own political group called the Patriotic League of Uganda. Many people in the country believe this is a sign of a dynastic transition. They fear that power will simply be handed from the father to the son. This has added a new layer of tension to the security presence during the current vote.

The youth of Uganda are particularly concerned about this potential succession. They have lived their entire lives under one leader and are eager for change. The heavy military deployment is seen by some as a way to ensure the transition goes according to the government’s plan. If the public perceives the election as unfair, the risk of unrest increases. The state uses the memory of the chaotic 1970s to justify this militarized approach. They argue that only the current leadership can maintain the stability won during the Bush War (observer.ug). However, many citizens believe that true stability can only come from a fair and transparent democratic process.

The Complex Role of the United States

The relationship between Uganda and the United States is complicated. Under the administration of President Donald Trump, the U.S. continues to view Uganda as a vital security partner in East Africa (state.gov). Uganda provides thousands of troops to fight Al-Shabaab in Somalia. This military cooperation is a cornerstone of regional stability. Because of this partnership, the U.S. provides nearly one billion dollars in annual aid to the country. Most of this funding goes toward security assistance and health programs like PEPFAR (state.gov).

At the same time, the U.S. government has expressed concern over human rights violations. Following the violence in the 2021 election, some Ugandan officials faced visa restrictions (observer.ug). The U.S. also removed Uganda from a major trade pact because of concerns over political repression and laws targeting specific groups. This “security-for-silence” trade-off is often criticized by human rights advocates. They argue that military aid subsidizes the very forces used to crack down on domestic protesters. The challenge for the U.S. is balancing its security interests with its stated commitment to democratic values on the continent.

Resistance Through Digital Innovation

Despite the blackouts and surveillance, Ugandans have found ways to resist. During the 2021 election, the opposition developed the U Vote app (tpr.org). This tool allowed ordinary citizens to take photos of official result forms and upload them to a central server. The goal was to create a parallel tally of the votes to prevent the government from changing the numbers. Even though the state blocked the app and arrested its monitors, it represented a shift toward citizen journalism. It showed that technology could be a tool for transparency as much as it is a tool for control.

Organizations like Reporters Without Borders (RSF) also play a critical role. They monitor the safety of journalists and provide legal support to those targeted by the regime (observer.ug). Uganda has dropped in the global press freedom rankings due to the frequent assault of reporters covering opposition events (observer.ug). However, the persistence of local journalists and digital activists keeps the world informed. Even when the internet is cut, information eventually leaks out through virtual private networks or physical transport across borders. The battle for information in Uganda is a testament to the resilience of those who believe in the right to speak and organize freely.

Conclusion: The Future of Ugandan Democracy

The 2026 election is a reflection of a regime that has adapted its survival tactics for the modern age. The transition from a liberation movement to an entrenched power has been marked by the erosion of constitutional limits. While the headlines focus on the “tense vote” and the “internet blackout,” the real story is about the struggle for the future of a young nation. The government uses security as a justification for silence, but the underlying desire for change among the youth remains strong. The historical memory of past wars is no longer enough to satisfy a generation that wants a voice in how they are governed.

As the blackout continues, the world watches to see if the outcome will be accepted by the people. The use of digital tools to suppress the vote has set a dangerous precedent. However, the creativity and courage of the Ugandan people provide a glimmer of hope. Whether through music, apps, or peaceful protest, the demand for accountability persists. The history of Uganda shows that while power can be maintained through force and control, true legitimacy can only be earned through the will of the people. The headlines of 2026 are just the latest chapter in a long journey toward a truly democratic Uganda.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.