Why Did History Hide the Teenager Who Sparked the Bus Boycott?

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

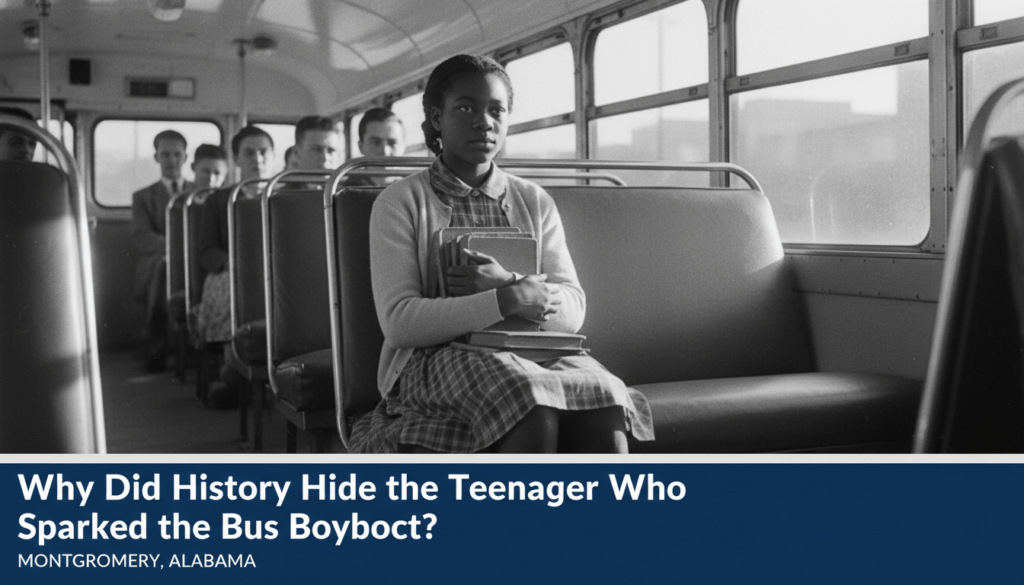

The passing of Claudette Colvin on January 13, 2026, marks a somber milestone in the story of American freedom (theguardian.com). She was 86 years old when she died under hospice care in Texas. For many decades, her name was a footnote in history books. Most people know about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott. However, the true spark of that movement began nine months earlier with a fifteen-year-old girl. Claudette Colvin stood up for her rights by staying in her seat. She was a pioneer who faced the full weight of the law long before the movement became a national sensation. Her life story provides a deep look at how history is made and who gets to be the face of it.

In the current political climate of 2026, under the administration of President Donald Trump, the legacy of civil rights remains a central topic of debate. Colvin lived long enough to see her record cleared and her name restored to its rightful place. She witnessed a world change from the strict segregation of the 1950s to the complex challenges of the modern era. Her journey from a “forgotten” teenager to a celebrated icon is a testament to her strength. It also highlights the difficult choices made by leaders during the struggle for equality. Understanding her story requires looking back at the world she lived in during 1955. It was a world governed by laws designed to keep people apart based on the color of their skin.

The Demographic Gap (1955)

Percentage of Montgomery Bus Riders Who Were Black

75%

Despite providing the majority of revenue, Black riders held zero legal power in the transit system.

The Schoolgirl Who Stayed Seated

On March 2, 1955, Claudette Colvin was a student at Booker T. Washington High School in Montgomery, Alabama (wikipedia.org). She was riding the bus home after a day of classes. That week was “Negro History Week,” a time dedicated to learning about the achievements of African Americans. Her teachers had been discussing figures like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth (oprahdaily.com). These lessons had a profound impact on the young girl. She felt the spirit of these ancestors with her as she sat on that bus. She later said that she felt like Sojourner Truth was pushing down on one shoulder and Harriet Tubman on the other (theguardian.com). This education was a form of intellectual resistance against a system that tried to make her feel inferior.

When the bus became crowded, the driver ordered Colvin and three other Black students to move (wikipedia.org). The other three students complied with the order. Colvin remained in her seat because she felt she had paid her fare and had a constitutional right to sit there (britannica.com). The driver called the police, and the situation quickly turned violent. Two officers, Thomas J. Ward and Paul Headley, dragged the teenager from the bus (theguardian.com). They handcuffed her and took her to an adult jail instead of a juvenile facility. She was charged with disturbing the peace and violating segregation laws. Most seriously, she was charged with assaulting a police officer (theguardian.com). This final charge was a common tactic used to discredit activists and ensure harsher sentences.

The origins of Black Studies and the specific history taught in her school gave her the courage to resist. Her refusal was not an impulsive act of a teenager. It was a calculated stand against a system she knew was wrong. The police reported that she kicked and scratched them, but Colvin maintained she was only defending herself (theguardian.com). She spent hours in a jail cell, terrified but resolute. Her arrest sent shockwaves through the local Black community. Leaders in Montgomery began to wonder if this was the case they had been waiting for. They wanted to challenge the bus laws in court, and Colvin seemed like a strong candidate at first.

The Violent Enforcers of Segregation

The Jim Crow laws of 1955 were not just social customs. They carried the full weight of the legal system (britannica.com). These statutes mandated racial segregation in all public facilities across the South. The Supreme Court had supported this with the 1896 *Plessy v. Ferguson* decision (britannica.com). This ruling established the “separate but equal” doctrine. In reality, facilities for Black Americans were almost always inferior and underfunded. This system influenced every part of daily life, from schools and hospitals to the very buses Colvin used to get to school. These laws were a direct result of how post-Civil War reconstruction had failed to protect the rights of newly freed people.

Police officers in the South acted as the primary enforcers of these laws. Their role was to maintain the racial hierarchy through intimidation and force. When Colvin refused to move, she was not only defying a bus driver. She was defying the entire social order of the state of Alabama. The assault charge placed on her was particularly damaging (theguardian.com). It was a felony that stayed on her record for over sixty years. This charge was designed to make her look like a “delinquent” rather than a civil rights hero. The legal system was rigged to punish any form of Black resistance. Even as a child, Colvin was treated as a dangerous criminal for wanting to keep her seat.

During this era, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was the leading force against segregation (naacp.org). They used strategic litigation to fight these laws in court. The NAACP had recently won the *Brown v. Board of Education* case in 1954 (naacp.org). This victory gave many people hope that change was possible. However, the organization was very careful about which cases they took to trial. They needed plaintiffs who could withstand the intense scrutiny of the white press and the biased court system. They looked for individuals who fit a specific image of “respectability.” Unfortunately for Colvin, her status as a “feisty” teenager made some leaders hesitate (britannica.com).

Daily Economic Impact of the Protest

Estimated Revenue Lost by Montgomery City Lines (1955-1956)

Equivalent to roughly $30,000 – $40,000 per day in modern currency.

The boycott lasted 381 days, causing massive financial strain on the city.

The Hidden Walls of Respectability

Respectability politics played a major role in the strategy of the Civil Rights Movement. Leaders like E.D. Nixon and a young Martin Luther King Jr. wanted symbols who were beyond reproach (britannica.com). They sought activists who were “wealthy, chaste, and conformist” to win over white allies. Claudette Colvin was a working-class teenager with dark skin. Shortly after her arrest, she became pregnant while unmarried (britannica.com). Movement leaders feared that the white media would use her pregnancy to paint her as “immoral.” They believed this would distract from the legal issue of segregation. As a result, they decided not to make her the face of the planned boycott.

Rosa Parks was a different kind of candidate. She was an adult, a seamstress, and the secretary for the local NAACP (britannica.com). She had a professional image and lighter skin, which leaders felt was more “palatable” for a national audience. While Parks was also a dedicated activist, her selection was a strategic choice (britannica.com). This decision reflects the internal biases that existed even within the movement. People often forget how Black women contributed to the struggle while facing both racism from the outside and sexism from within. Colvin was essentially pushed into the shadows because she did not fit the “perfect” mold of a hero at that time.

The use of these labels also extended to other marginalized groups. For example, history shows how the FBI weaponized homophobia to divide civil rights leaders and discredit their work. The movement felt it had to be extremely cautious to survive. Colvin understood the logic of the leaders, but it still had a personal cost. She was labeled a “troublemaker” in her community. She found it difficult to find steady work or finish her education in Montgomery (theguardian.com). While the world began to celebrate Rosa Parks, Colvin lived with the consequences of her defiance in relative obscurity. She did not harbor resentment, but she did feel the weight of being forgotten by the very movement she helped start.

The Legal Battle for Constitutional Equality

While the Montgomery bus boycott is famous for its economic impact, it did not legally end segregation. The law changed because of a federal lawsuit called Browder v. Gayle (wikipedia.org). Because Rosa Parks had a criminal case in the state courts, her lawyers feared it would be delayed for years (stanford.edu). To bypass the biased Alabama court system, attorney Fred Gray filed a civil suit in federal court. He chose four women to be the plaintiffs: Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Mary Louise Smith, and Claudette Colvin (wikipedia.org). Colvin was a star witness in this case. Her testimony was crucial in proving that segregation was a violation of the 14th Amendment.

The 14th Amendment contains the Equal Protection Clause. This clause says that no state can deny any person “equal protection of the laws” (britannica.com). The lawyers argued that “separate but equal” was inherently unequal. Colvin stood before a panel of three federal judges and told her story. Her bravery in court was just as important as her bravery on the bus. In June 1956, the judges ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional (wikipedia.org). The Supreme Court later upheld this decision. The boycott only ended once the federal government forced Montgomery to integrate its buses in December 1956 (wikipedia.org). Without Colvin and the other plaintiffs, the boycott might have lasted even longer without a legal victory.

This legal strategy was essential because it challenged the foundation of Jim Crow. The NAACP focused on overturning segregation through the courts because they knew the legislature would not act (naacp.org). Colvin’s participation in the lawsuit shows that she was still active in the struggle, even if she was not the public face of it. She faced intense pressure and threats for her role in the case. However, she remained committed to the cause of justice. She was one of the few who stood up in a courtroom to tell the truth about the brutality of the system. Her legal victory changed the law for everyone, yet her name remained largely unknown to the general public for many years.

Timeline of a Legacy

Claudette Colvin is arrested at age 15 for refusing to give up her bus seat.

She serves as a key plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle, ending bus segregation.

Her criminal record is officially expunged by an Alabama judge after 66 years.

Colvin passes away at age 86, recognized as a founding mother of the movement.

Escaping Retaliation in the North

By 1958, life in Montgomery had become unbearable for Claudette Colvin. She was blacklisted from jobs and constantly harassed by those who opposed civil rights (theguardian.com). The pressure of being a teenage mother in a hostile environment was overwhelming. She decided to move to New York City to start a new life. In the North, she hoped to find the anonymity and opportunity that Alabama denied her. She found work as a nurse’s aide in a Manhattan nursing home (theguardian.com). She spent thirty-five years in that role, quietly serving others. She rarely talked about her past as a civil rights pioneer during those decades.

This move was a common experience for many activists who faced economic retaliation. In the Jim Crow South, the power of white employers was used to crush dissent. If a person stood up for their rights, they often lost their ability to feed their family. Colvin’s “juvenile record” followed her, even though she moved away. She remained on an “indefinite probation” that was never officially closed (cbsnews.com). This meant she lived in a state of legal limbo for much of her life. She feared that any minor interaction with the police could lead to her being sent back to jail because of her 1955 arrest. This fear was a persistent shadow over her life in New York.

Despite the challenges, Colvin raised her family and built a stable life. She watched from a distance as the movement she helped start grew into a global phenomenon. She saw the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 pass (naacp.org). She knew that her actions had contributed to these historic wins. However, she remained a private person until the late 2000s. It was only then that historians and journalists began to seek her out. They realized that the story of the Montgomery bus boycott was incomplete without her. A biography published in 2009 helped introduce her to a new generation of Americans (theguardian.com).

A Triumphant End to a Long Journey

The final years of Claudette Colvin’s life were filled with the recognition she had long deserved. In October 2021, at the age of 82, she decided to take one final stand (apnews.com). She filed a petition to have her juvenile record expunged. She wanted to show her grandchildren and great-grandchildren that she was not a criminal. Judge Calvin Williams in Montgomery granted her request in December 2021 (cbsnews.com). He ordered that her record be sealed and destroyed. He stated that her actions in 1955 were “inspired, not illegal.” This was a powerful moment of justice that took over sixty years to arrive.

In her later years, Montgomery began to honor her as well. A street was named Claudette Colvin Drive, and her image was included in murals and monuments (theguardian.com). She was no longer the “troublemaker” but a founding mother of the movement. Her passing in 2026 marks the end of an era. She was one of the last living links to the early days of the struggle in Montgomery. Her family stated that she never felt bitter toward Rosa Parks (theguardian.com). She understood that “history had a plan” and that different people played different roles. Her legacy is a reminder that everyday people, even teenagers, have the power to change the world.

The story of Claudette Colvin teaches us that history is often more complex than the headlines suggest. It is a story of courage, sacrifice, and the slow march toward justice. While she lived in obscurity for a long time, she died knowing that her truth was finally told. She proved that one person’s refusal to accept injustice can spark a fire that burns down a system of oppression. As we look at the challenges of 2026, her spirit of defiance remains a guide. She was a woman who knew her worth and refused to move, even when the world tried to push her aside. Her seat in history is now permanently reserved.

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.