Breaking the Chains: How Maryland, Georgia, and Virginia Lead the Fight Against Racial Injustice

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

Three states are making headlines as they push forward with groundbreaking legislation to address the deep racial inequities embedded within America’s criminal justice system. Maryland’s Second Look Act, Virginia’s constitutional amendment for automatic voting rights restoration, and Georgia’s ongoing criminal justice reforms represent more than policy changes. They signal a fundamental shift in how states confront the legacy of mass incarceration and systemic racism.

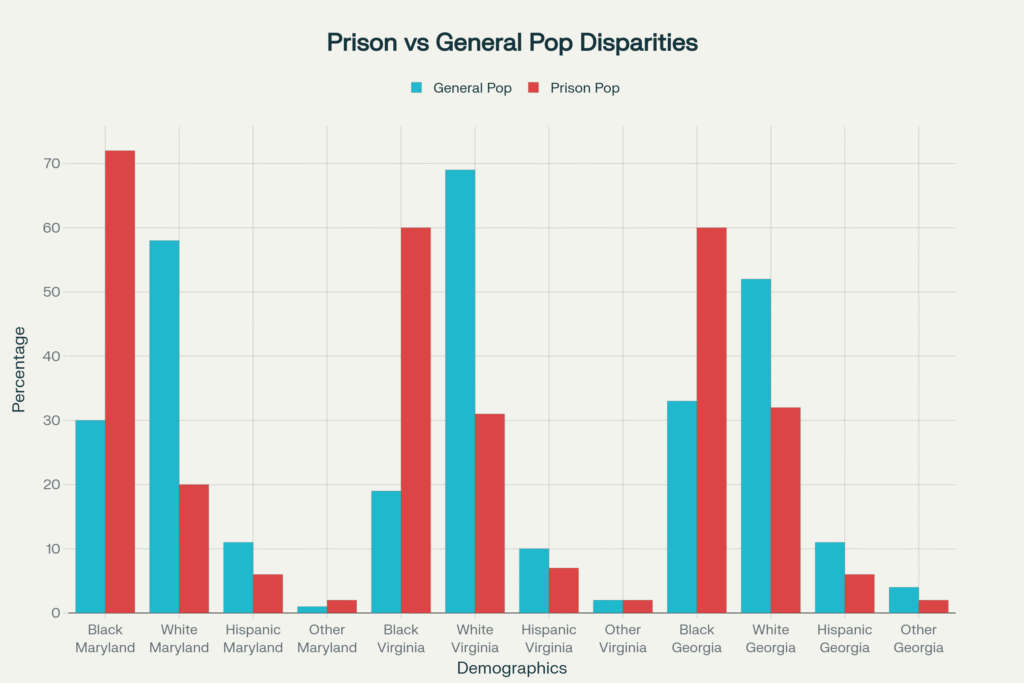

These legislative efforts carry profound significance for Black communities, who have borne the disproportionate burden of harsh sentencing practices and voter disenfranchisement for generations. The numbers tell a stark story: Black Americans constitute 72% of Maryland’s prison population while representing only 30% of the state’s residents (The Sentencing Project). Virginia’s felony disenfranchisement affects an estimated 9.8% of the state’s Black voting-age population (ACLU of Virginia). Meanwhile, Georgia continues to have the seventh-highest incarceration rate nationally, with profound racial disparities (R Street Institute).

Maryland’s Second Look Act: A Path to Redemption and Justice

Maryland made history in April 2025 when Governor Wes Moore signed the Second Look Act into law, creating a pathway for sentence reconsideration grounded in rehabilitation rather than retribution (ACLU of Maryland). The legislation allows individuals who were convicted of offenses occurring between ages 18 and 25 and have served at least 20 years to petition courts for sentence modification based on demonstrated rehabilitation.

The act emerged from compelling evidence of successful rehabilitation among long-term prisoners. Research from Maryland’s own experience with the “Ungers” case proves the potential for redemption. In 2012, when 235 people with unconstitutional sentences became eligible for release, prosecutors often negotiated their freedom rather than pursue costly retrials. These individuals, nearly 90% of whom were Black, had served an average of 39 years. By 2021, they maintained a recidivism rate of less than 3%, compared to 40% for the general prison population (Maryland Alliance for Justice Reform).

However, the final version of the bill includes significant limitations that advocates argue undermine its potential impact. The legislation excludes individuals serving life without parole and those convicted of sex-related offenses, creating what critics call an arbitrary distinction about who deserves a second chance (The Sentencing Project). These exclusions particularly affect Black Marylanders, as 82% of those serving life sentences were under 25 at the time of their offense, the highest rate in the nation (ACLU of Maryland).

Maryland Second Look Act impact statistics based on legislative analysis and historical data. Sources: The Sentencing Project, ACLU of Maryland

The Second Look Act represents a critical step toward addressing Maryland’s status as having some of the worst racial disparities in incarceration nationally. The Maryland Equitable Justice Collaborative, formed by the state’s Attorney General and Public Defender offices, documented the stark reality: Black people account for 51% of arrests, 59% of the jail population, 71% of the prison population, and 71% of the parole population, despite representing only 30% of the state’s residents (Maryland Equitable Justice Collaborative).

Virginia’s Constitutional Amendment: Restoring Democratic Participation

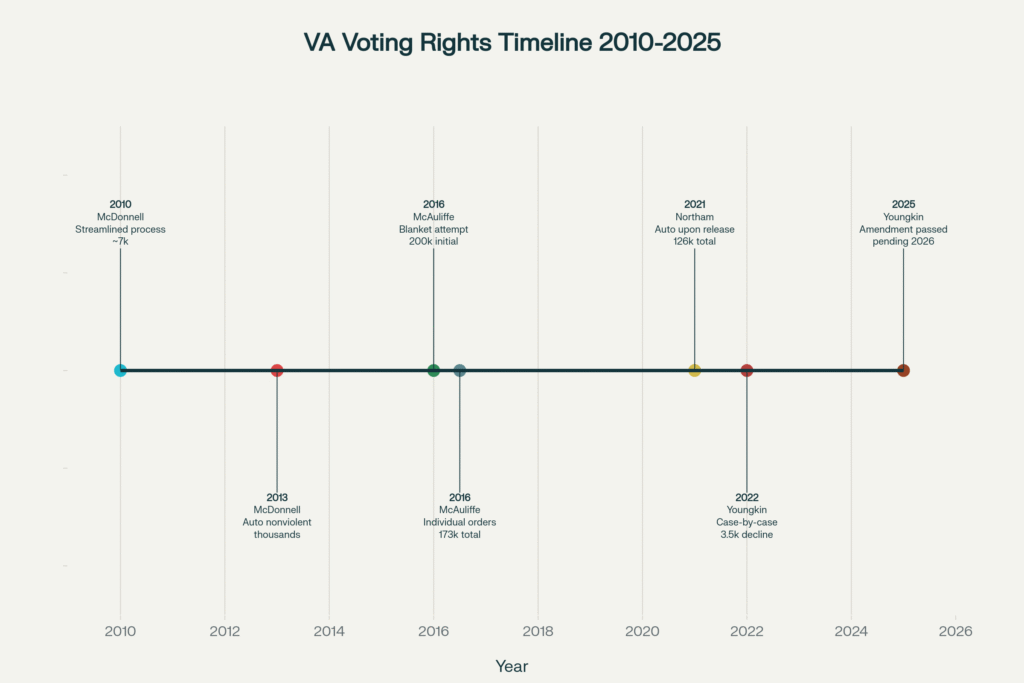

Virginia stands on the threshold of a historic transformation in voting rights. The state legislature passed a constitutional amendment (HJ2/SJ248) that would automatically restore voting rights to all eligible citizens upon completion of their felony sentences, ending the Commonwealth’s role as the only state requiring gubernatorial approval for rights restoration (ACLU of Virginia).

The amendment gained significant bipartisan support, passing the House 55-42, and must pass again in the 2026 legislative session before appearing on the November 2026 ballot for voter approval (ACLU of Virginia). If successful, it would transform the landscape for approximately 260,000 disenfranchised Virginians, including a disproportionate number of Black residents who face disenfranchisement at rates exceeding 9.8% of the Black voting-age population (Virginia Conservation Network).

The current system’s roots trace back to Virginia’s 1902 constitution, written explicitly to suppress Black political participation alongside other Jim Crow tactics like literacy tests and poll taxes (Virginia Conservation Network). The discriminatory intent was clear: convention president John B. Knox stated the goal was “to establish white supremacy in this state” through legal rather than violent means (The Marshall Project).

The amendment comes after years of political whiplash on voting rights restoration. Democratic governors Terry McAuliffe and Ralph Northam restored rights to nearly 300,000 Virginians combined, implementing increasingly streamlined processes that culminated in automatic restoration upon release from incarceration (The Sentencing Project). However, Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin reversed this progress, returning to a case-by-case system that has dramatically reduced restorations from over 12,000 annually to just 1,641 in 2024 (VPM News).

Furthermore, Youngkin’s administration mistakenly purged nearly 3,400 people from voter rolls in 2023 after they had already received rights restoration, demonstrating the arbitrary and error-prone nature of the current system (Common Cause). This chaos underscores the urgent need for constitutional clarity that removes voting rights from political manipulation.

Georgia’s Ongoing Battle Against Mass Incarceration

Georgia presents a complex picture of criminal justice reform efforts amid persistent challenges. While the state implemented significant changes through its Justice Reinvestment Initiative in 2012, reducing the prison population by 6% and averting $264 million in corrections costs, it still maintains the seventh-highest incarceration rate nationally with 881 per 100,000 residents (R Street Institute).

The state’s criminal justice landscape reveals troubling patterns of racial disparity. Black Georgians face incarceration at rates far exceeding their representation in the general population, though comprehensive recent statistics remain difficult to obtain due to limited public reporting (The Sentencing Project). The Georgia Budget and Policy Institute emphasizes that historic and current punitive policies perpetuate the disproportionate incarceration of Black Georgians while exacerbating economic hardships that often contribute to involvement in the justice system (Georgia Budget and Policy Institute).

Recent developments have created mixed signals about Georgia’s commitment to reform. In 2024, Governor Brian Kemp signed Senate Bill 63, which critics argue creates a two-tiered justice system where wealth determines pretrial detention. The ACLU of Georgia condemned the legislation as “cruel, costly, and counterproductive,” noting that it forces more people to remain jailed simply because they are poor or mentally ill (ACLU of Georgia).

However, progressive advocates continue pushing for meaningful reforms. Organizations like the Southern Center for Human Rights maintain focus on addressing conditions of confinement and supporting legislators in understanding root causes of dysfunction in Georgia’s jails and prisons (Southern Center for Human Rights). The Department of Justice’s 2024 reports detailing human rights violations in Georgia Department of Corrections facilities provide a roadmap for necessary remedial measures, though implementation remains challenging.

Georgia criminal justice reform timeline based on legislative records and civil rights advocacy. Sources: CSG Justice Center, ACLU of Georgia

The Historical Roots of Contemporary Injustice

Understanding these current reform efforts requires examining their historical context within America’s legacy of racial oppression through the criminal justice system. The modern era of mass incarceration began in the 1970s, but its roots extend much deeper into American history, particularly the post-Reconstruction period when Southern states sought new methods to control newly freed enslaved people.

The statistics reveal the devastating impact of this history. Black Americans are imprisoned at 5.0 times the rate of whites nationally, while American Indians and Latinx people face imprisonment at 4.2 times and 2.4 times the white rate respectively (The Sentencing Project). These disparities become even more stark in certain states: California, Connecticut, Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, Maine, and Wisconsin imprison their Black residents at over 9 times the rate of their white residents (The Sentencing Project).

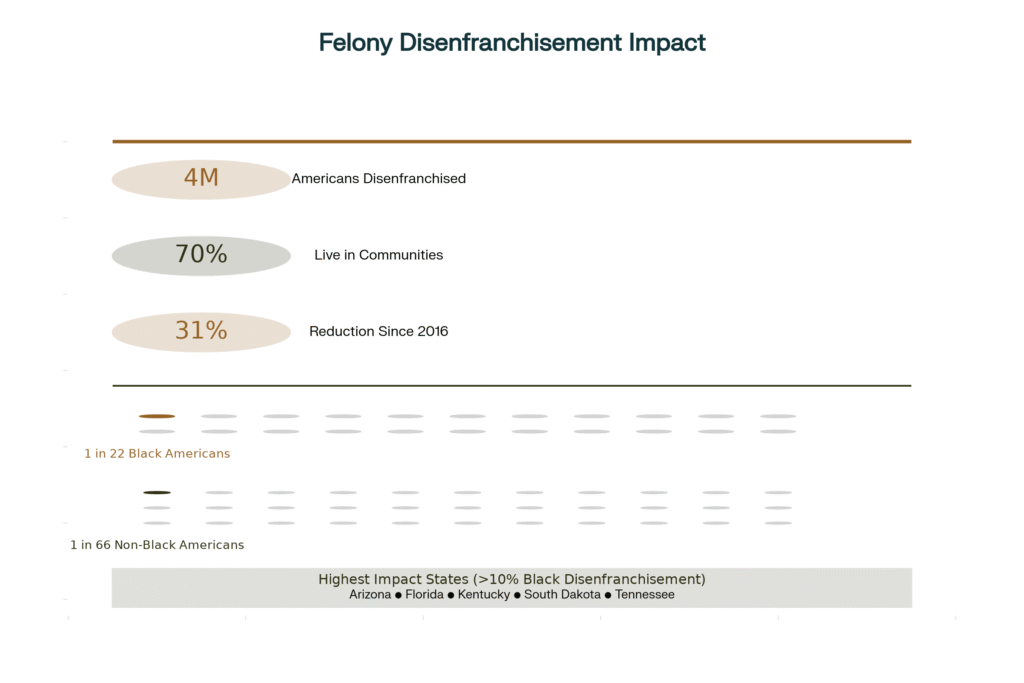

The connection between historical oppression and contemporary disenfranchisement becomes clear when examining felony voting bans. These laws originated during the post-Civil War period as Southern states sought legal mechanisms to suppress Black political participation after the 15th Amendment prohibited explicit racial voting restrictions. Alabama’s 1901 constitution exemplified this strategy, declaring persons “convicted of a felony involving moral turpitude” ineligible to vote without rights restoration (The Marshall Project). The language was deliberately vague to allow discriminatory enforcement while remaining constitutionally plausible.

Today, this Jim Crow-era strategy affects 4 million Americans, with Black citizens representing 2.2 million of the disenfranchised despite comprising less than 15% of the population (Center for Public Integrity). The racial impact varies dramatically by state, with Tennessee, Florida, Kentucky, South Dakota, and Arizona disenfranchising over 10% of their Black voting-age populations (Legal News).

Federal sentencing data provides additional evidence of persistent racial bias within the system. Black males receive federal sentences that are 13.4% longer than comparable white males, while Hispanic males receive sentences 11.2% longer than whites (U.S. Sentencing Commission). These disparities largely stem from prosecutorial charging decisions, with Black arrestees facing 1.75 times higher odds of receiving charges carrying mandatory minimum sentences compared to white arrestees for similar crimes (University of Michigan Law Review).

The cumulative effect of these disparities has created what scholars term the “era of mass incarceration,” where the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment for Black men born in 2001 remains one in five, compared to one in 20 for white men (The Sentencing Project). Although this represents improvement from the peak rate of one in three for Black men born in 1981, it still demonstrates the profound racialized nature of American criminal justice.

Breaking Generational Cycles Through Legislative Action

The current wave of reform legislation in Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia goes beyond policy adjustments. These measures address generational cycles of disadvantage that have affected Black families and communities for decades. Research demonstrates that parental incarceration affects approximately 2.7 million children, with Black children experiencing parental incarceration at rates 7.5 times higher than white children (Prison Policy Initiative).

Maryland’s Second Look Act acknowledges that people can change and mature, particularly those who were young adults when they committed their offenses. The emphasis on rehabilitation over retribution reflects growing understanding of adolescent brain development and the potential for redemption. Moreover, the act recognizes how racial bias in sentencing has created disparately harsh punishments for Black defendants, providing a mechanism to address these historical injustices.

Virginia’s constitutional amendment offers an even more fundamental shift by removing voting rights from political manipulation. The amendment would end a system where governors can essentially choose their electorate by determining which formerly incarcerated people regain political voice. This arbitrary power has proven especially harmful to Black communities, who face both higher rates of criminal justice involvement and subsequent civic exclusion.

The broader implications extend beyond individual cases to community empowerment and democratic participation. When people with criminal records regain voting rights, they become stakeholders in policy decisions affecting their neighborhoods, families, and futures. Research indicates that civic engagement, including voting, reduces recidivism rates and supports successful reintegration (Fair Elections Center).

Why Contemporary Reforms Matter for Black Communities Today

These legislative changes arrive at a critical moment for Black communities facing multiple intersecting challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affected Black families, while economic inequality, housing instability, and health disparities create conditions that increase involvement with the criminal justice system. Reform measures that reduce incarceration and restore civic participation provide essential tools for community resilience and empowerment.

The economic implications alone justify these reforms. The direct costs of mass incarceration approach $80 billion annually, but indirect costs, including lost productivity, family disruption, and community destabilization, multiply these figures (FWD.us). When people receive appropriate sentences and maintain civic engagement, communities benefit from their contributions rather than bearing the costs of their exclusion.

Furthermore, these reforms align with growing public support for criminal justice changes. Recent polling indicates 81% of likely voters support criminal justice reform, with significant bipartisan backing (FWD.us). This support transcends political affiliations, suggesting sustainable momentum for continued progress.

The interconnected nature of these reforms also creates positive feedback loops. When Maryland provides second chances through sentence review, more people return to communities with stable housing and employment. When Virginia restores voting rights automatically, these returning citizens can participate in electing officials who support evidence-based criminal justice policies. When Georgia addresses conditions of confinement and sentencing disparities, fewer families experience the trauma of unnecessary separation.

However, significant challenges remain. Conservative opposition continues fighting these reforms through legislative amendments, court challenges, and administrative obstacles. The exclusions written into Maryland’s Second Look Act demonstrate how compromise can limit the transformative potential of the law. Virginia’s amendment still requires passage in 2026 and voter approval before taking effect. Georgia’s recent bail legislation shows how reform can face setbacks even amid broader progress.

Additionally, these state-level reforms occur within a federal system where national policies significantly shape outcomes. Federal sentencing guidelines, immigration enforcement, drug policy, and funding formulas all influence how local reforms function in practice. The potential for federal policy reversals under different administrations creates uncertainty about sustained progress.

These reforms represent just the beginning of necessary changes to address centuries of racial injustice within American criminal justice. While Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia take important steps forward, comprehensive transformation requires sustained commitment to evidence-based policies that prioritize human dignity, community safety, and racial equity. The legislation emerging from these three states provides models for other jurisdictions while demonstrating that meaningful change remains possible when communities organize, advocate, and vote for justice.

The history behind today’s headlines reveals both the depth of historical injustice and the possibility of redemption through collective action. As these reforms advance through legislative processes and implementation, they offer hope that America can finally begin dismantling systems designed to oppress and replace them with structures that support human flourishing across all communities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.