When AI Mistakes Snacks for Guns: The Dangerous Legacy of Surveilling Black Youth

The History Behind The Headlines

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

A Terrifying Night After Football Practice

Taki Allen was doing what millions of teenagers do after sports practice. The 16-year-old student-athlete at Kenwood High School in Baltimore County finished his bag of Doritos, crumpled up the empty wrapper, and put it in his pocket while waiting for his ride home on October 20, 2025 (Bin News). Twenty minutes later, eight police cars surrounded him. Officers emerged with guns drawn, shouting commands at the confused teen (Atlanta Black Star).

“At first, I did not know where they were going until they started walking toward me with guns, talking about, ‘Get on the ground,’ and I was like, ‘What?'” Allen told local news outlets (Bin News). Officers forced him to his knees, handcuffed him, and searched him. Only then did they discover the truth: an artificial intelligence gun detection system had flagged his chip bag as a firearm (Salon).

Throughout the ordeal, one question dominated Allen’s thoughts: “Am I gonna die? Are they going to kill me?” (Atlanta Black Star). His grandfather, Lamont Davis, expressed what many in the Black community already knew. “God forbid, my grandson could be dead if he flinched or twitched,” Davis said (Fox Baltimore).

The Technology Behind the Terror

The system that mistook a snack for a weapon is called Omnilert Gun Detect. Baltimore County Public Schools deployed it across the district in 2023 as part of a $2.6 million contract (Fox Baltimore). The AI-powered software analyzes footage from the district’s 7,000 existing security cameras. It claims to detect firearms in less than a second and alert school officials and law enforcement in real time (Omnilert).

However, the Doritos incident was not an isolated malfunction. Earlier in 2025, the same Omnilert system failed to detect an actual gun during a school shooting in Nashville. One student died and another was injured in that attack (Fox Baltimore). The system missed the weapon because the shooter did not brandish it within view of the cameras (CNN).

Despite these failures, school superintendent Myriam Rogers defended the technology. She insisted the system “did what it was supposed to do” by flagging a potential threat for human review (GovTech). Yet human reviewers had already determined there was no weapon and canceled the alert before police arrived. The school principal overlooked the cancellation and contacted law enforcement anyway (BBC).

Omnilert stood by its product. The company called the Doritos bag a “false positive” but claimed “the process functioned as intended: to prioritize safety and awareness through rapid human verification” (ABC7). This response ignores a fundamental problem: artificial intelligence systems are not neutral arbiters of safety.

The Algorithmic Gaze: How AI Learns to Be Racist

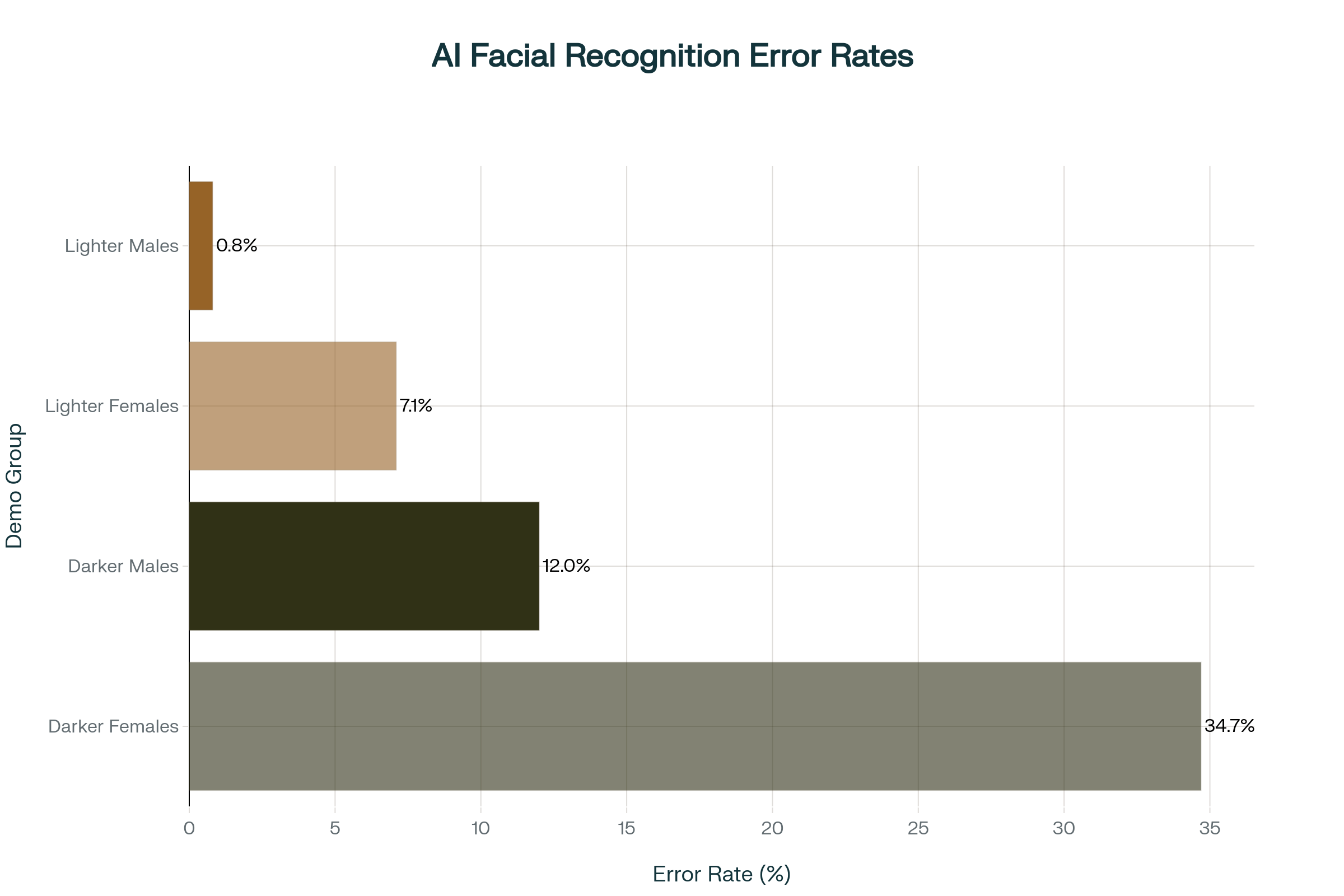

The technology that threatened Taki Allen’s life operates within a broader ecosystem of racially biased artificial intelligence. In 2018, computer scientist Joy Buolamwini exposed alarming disparities in facial recognition systems. Her groundbreaking research at MIT revealed that commercial AI systems misclassified Black women nearly 35 percent of the time while achieving near-perfect accuracy for white men (ACLU).

Buolamwini discovered this bias when facial recognition software failed to detect her own face. She had to wear a white mask to be recognized by the system (MIT News). Testing images of iconic Black women like Michelle Obama, Serena Williams, and Oprah Winfrey produced similar failures. The systems either misclassified them or did not detect them at all (Duke Sanford).

The bias is not accidental. AI systems learn from the data they are fed. If that data reflects historical patterns of racism, the technology will reproduce and amplify those patterns (Morgan Magazine). Police use mugshot databases to train facial recognition systems. Since Black people face arrest for crimes at far higher rates than white people, their faces dominate these databases (ACLU). The technology then targets Black communities more aggressively, generating more arrests and perpetuating a vicious cycle (NAACP).

AI models also assign speakers of African American English to lower-prestige jobs and issue more convictions in hypothetical criminal cases. Some systems even recommend more death penalties for Black defendants (UChicago News). The racial bias embedded in these algorithms mirrors attitudes from the 1930s or worse (UChicago News).

From Slave Passes to Smart Cameras: Centuries of Surveillance

The surveillance that endangered Taki Allen represents the latest chapter in a much longer story. For centuries, white institutions have monitored, tracked, and controlled Black bodies through evolving forms of technology. Understanding this history reveals how AI surveillance systems are not innovations but continuations (Just Tech SSRC).

During slavery, plantation owners created one of America’s first identification systems: the slave pass. These written documents allowed enslaved people to travel off plantations (Privacy SOS). The system required keeping Black people illiterate so they could not forge or read their own passes. Laws banning Black literacy existed primarily to maintain the integrity of this surveillance apparatus (Privacy SOS).

In 18th-century New York, lantern laws mandated that Black, mixed-race, and Indigenous enslaved people carry lit candles when walking after dark without a white person (DarkSky). Any white person could stop and interrogate people of color caught without a light. Violators faced up to 40 lashes (DarkSky). Scholar Simone Browne argues these lantern laws established the legal framework for modern stop-and-frisk policing practices (DarkSky).

After slavery ended, surveillance intensified. The FBI launched COINTELPRO in 1956, a covert program targeting civil rights and Black power movements (Wikipedia). Federal agents surveilled, infiltrated, and worked to “neutralize” leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and members of the Black Panther Party through tactics including assassination, imprisonment, and false criminal charges (Wikipedia). The program officially ended in 1971, but many of its surveillance techniques continue today (Wikipedia).

The School-to-Prison Pipeline Gets an Upgrade

Modern school policing emerged during the 1950s when white communities feared that Black children would disrupt newly integrated schools (Harvard Law Review). The New York City Police Department depicted Black students as “dangerous delinquents.” In Oakland, school police monitored and contained the Black Power movement and the Black Panther Party (Harvard Law Review).

The 1990s brought zero-tolerance policies fueled by hysteria about “super predators.” Politicians and media outlets described a coming wave of “relentlessly violent” young Black and Latino criminals (Temple News). The predicted crime wave never materialized. However, the policies remained, leading to explosive growth in school suspensions, expulsions, and arrests (End FMR Now).

Between 1975 and 2017, the percentage of public schools with police officers increased from 10 percent to more than 60 percent (End FMR Now). Black students bore the brunt of this expansion. During the 2017-2018 school year, Black students were suspended and expelled at more than five times the rate of white students (End FMR Now). They are also arrested at school at rates far exceeding their enrollment (Center for Public Justice).

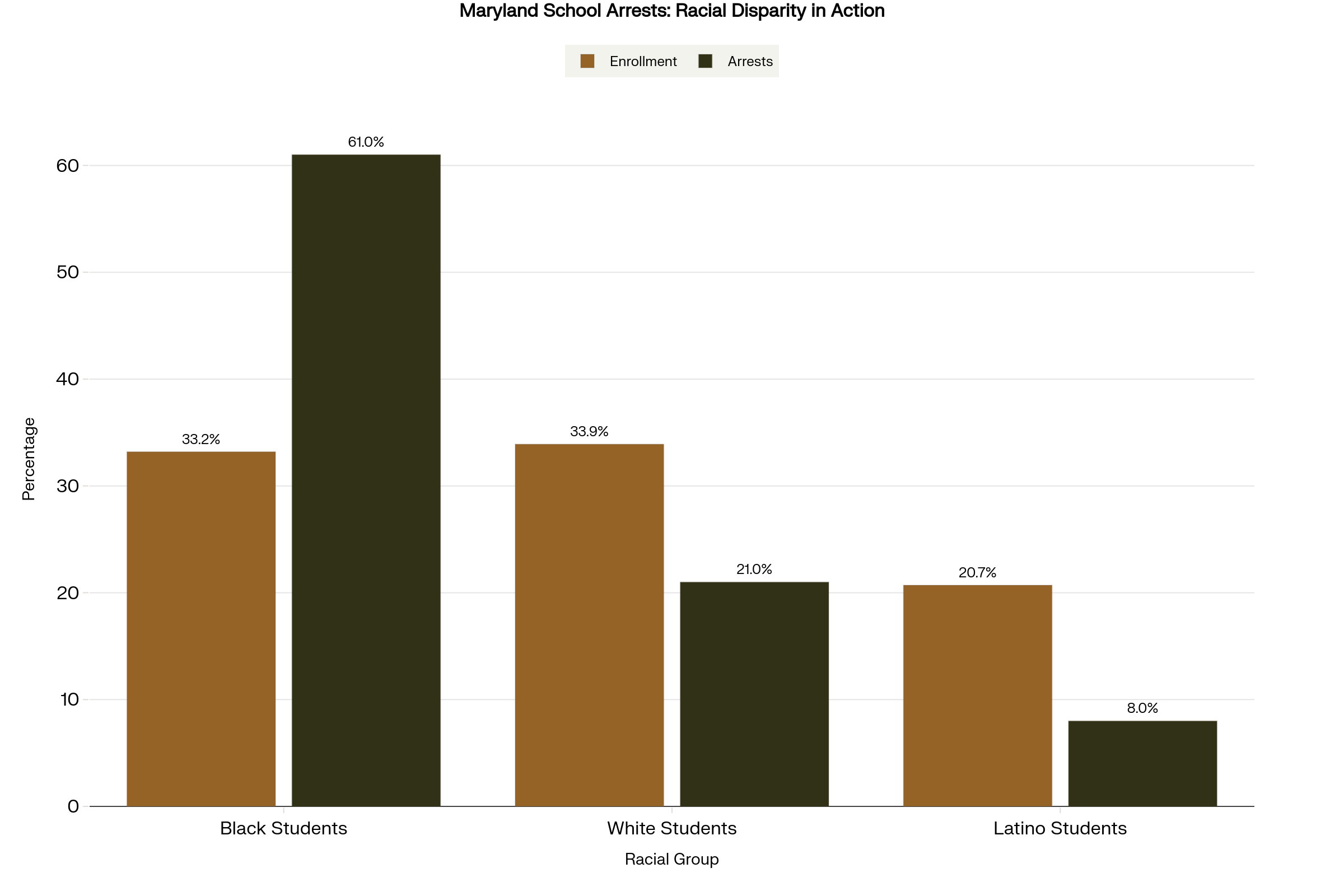

In Maryland, the disparities are stark. Black students represented 33 percent of the school population in 2022-2023 but accounted for 61 percent of school-based arrests (Afro). White students made up 34 percent of enrollment but only 21 percent of arrests (Afro). In some counties, Black students are arrested at rates 20 to 28 times higher than their white peers (Afro).

Research shows that police in schools do not make students safer. Officers rarely prevent crime. Instead, their presence leads to more arrests for minor infractions and increases the likelihood that students will drop out or enter the criminal legal system (Center for Public Justice). Police are also more likely to use force on young people than on adults, with Black children making up over 50 percent of victims despite comprising only 15 percent of the population (Center for Public Justice).

Civil Rights Organizations Demand Accountability

The incident at Kenwood High School sparked immediate outrage from civil rights organizations. The Randallstown NAACP and Associated Black Charities called it “a symptom of broader systemic bias and leadership failure” within Baltimore County Public Schools (Afro). Dr. Tekemia Dorsey, president of the Randallstown NAACP, said the event represents “not just a malfunction of technology but a failure of leadership and humanity” (Afro).

The NAACP documented several concerns in its response. The organization cited racial bias in the AI system, due process violations, and leadership failures (Afro). They argue the technology creates a climate of over-surveillance and aggressive policing. This hostile educational environment particularly impacts students of color who may feel criminalized simply for existing (Afro).

The civil rights group issued specific demands. They call for an independent civil rights audit of Baltimore County’s AI systems, public release of surveillance data, and suspension of AI use until bias reviews are complete (Afro). They also demand school leaders issue a public apology, disclose vendor contracts, and redirect funds toward counselors and restorative programs (Afro).

Baltimore City Councilman Mark Conway called for public hearings on AI surveillance systems in schools. He pointed out that both Baltimore City and Baltimore County approved multi-million dollar contracts without public discussion (Fox Baltimore). Baltimore City spent $5.46 million on Evolv Technologies, a company the Federal Trade Commission found had deceptively exaggerated its AI capabilities (Fox Baltimore).

“The public deserves a say before these systems are turned on in our schools, especially when emerging research shows that heavy surveillance in education disproportionately harms Black students and undermines learning outcomes,” Conway stated (Fox Baltimore). A 2022 study from Johns Hopkins and Washington University found that schools with increased surveillance experience higher suspension rates, lower math achievement, and lower college enrollment. Black students are four times more likely to attend highly surveilled schools (Fox Baltimore).

The ACLU emphasized that the real scandal is not that AI makes mistakes. The problem is that schools set up systems allowing those mistakes to trigger armed police responses against children (ACLU). “Humans should have been in the loop here — before police were deployed, guns drawn — and recognized a Doritos bag when they saw one,” the organization stated (ACLU).

The Human Cost of Algorithmic Error

Taki Allen’s experience left lasting trauma. He told reporters he no longer feels safe being outside after football practice. “I do not feel safe enough to be outside, especially when I am eating chips or drinking something. I just stay indoors until my ride comes,” he explained (New York Post).

The school offered no personal outreach or apology. Allen said officials simply told him the armed response was protocol (Fox Baltimore). His grandfather believes school leadership should have checked on the teen’s wellbeing. “I want [the principal] to reach out to him and go to his class and say, ‘Are you okay? Do you feel okay?'” Davis said (Fox Baltimore).

This lack of care reflects a broader pattern. School administrators and technology vendors prioritize system performance over student welfare. Superintendent Rogers insisted the AI system worked correctly even though it nearly got a Black teenager killed (GovTech). Omnilert defended its product despite acknowledging the false positive (ABC7).

The incident also traumatized other students who witnessed the armed confrontation. School officials sent a letter acknowledging how upsetting the event was for witnesses and offered counseling services (GovTech). However, no counseling can erase the lesson these students learned: their school views them as potential threats requiring armed containment.

Why Predictive Algorithms Fail Black Communities

AI gun detection systems like Omnilert operate on the same flawed logic as predictive policing algorithms. They analyze historical data to forecast future threats. When that historical data reflects centuries of racist policing practices, the technology inevitably reproduces racial bias (NAACP).

Black defendants are 77 percent more likely to be labeled high-risk for violent recidivism than white defendants, even when controlling for prior offenses, age, gender, and other factors (Research Archive). These algorithms create feedback loops. Police patrol Black neighborhoods more heavily because the data shows higher arrest rates there. More patrols lead to more arrests. More arrests generate more data showing Black communities as high-crime areas. The cycle repeats and intensifies (NAACP).

US Senators wrote to the Department of Justice noting that “mounting evidence indicates that predictive policing technologies do not reduce crime. Instead, they worsen the unequal treatment of Americans of color by law enforcement” (NAACP). The legislators called for ceasing funding for predictive policing systems until proper audits and due process considerations occur (NAACP).

Facial recognition errors have led to wrongful arrests of Black people. Portia Woodruff, eight months pregnant, was falsely arrested due to facial recognition mistakes (Duke Sanford). Robert Williams was misidentified and arrested in front of his young daughters (Duke Sanford). These cases demonstrate that AI bias has life-altering consequences, not just abstract statistical disparities.

The Broader Context of School Surveillance

The problems extend beyond gun detection systems. A 2025 study found that 86 percent of school-based online surveillance companies monitor students 24 hours per day, seven days per week (UCSD Today). These companies track student activity both during and outside school hours, often using AI with minimal human oversight (UCSD Today).

The surveillance reaches beyond school-issued devices. Thirty-six percent of companies claim to monitor student-owned phones and computers (UCSD Today). Some generate “risk scores” based on online behavior that can be viewed at the student, classroom, or school level (UCSD Today). These practices raise serious privacy concerns and normalize invasive monitoring without adequate transparency (New America).

The lack of transparency means communities cannot make informed judgments about these technologies (New America). Schools deploy AI systems without public discussion of their accuracy, bias rates, or impact on student wellbeing (Fox Baltimore). When failures occur, administrators deflect responsibility to the technology or claim protocols were followed (GovTech).

Conclusion: Why This Matters Today

When eight police cars surrounded Taki Allen over a bag of chips, they enacted a pattern older than the United States itself. For over 400 years, white institutions have used evolving surveillance technologies to monitor, control, and criminalize Black bodies. The methods change from slave passes to smart cameras. The underlying logic remains constant: Black people, especially Black youth, require aggressive monitoring because they pose inherent threats.

This incident matters because it exposes how artificial intelligence systems launder centuries of racist assumptions through claims of neutral objectivity. School officials can point to the algorithm and say they were just following protocol. Yet the protocol itself embeds racial bias at every level: in the decision to deploy AI surveillance primarily in schools serving Black students, in the historical data the algorithms learn from, in the assumption that Black teenagers eating snacks warrant armed police responses.

The story matters because it reveals who gets to be a child and who gets treated as a threat. White teenagers can eat chips, carry backpacks, and make sudden movements without triggering armed responses. For Taki Allen and millions of other Black youth, routine adolescent behaviors can become death sentences when filtered through surveillance systems trained on racist data (Word in Black).

Most importantly, this incident demonstrates that technological solutions to violence cannot work when built atop violent historical foundations. Schools that want genuinely safe environments must invest in counselors, mental health services, and restorative justice programs rather than AI systems that criminalize students (Afro). Communities must demand transparency, independent audits, and public oversight before allowing these systems in schools (Fox Baltimore).

The civil rights movement fought to integrate schools so Black children could receive quality education. Today’s surveillance systems threaten to undo that progress by transforming schools into extensions of the carceral state (Harvard Law Review). Black students are not threats requiring containment. They are children who deserve to eat snacks, laugh with friends, and wait for rides home without facing guns drawn over algorithmic errors.

Until we dismantle the surveillance systems built on racist foundations, incidents like the one at Kenwood High School will continue. The technology may get more sophisticated. The fundamental injustice remains unchanged. Black youth deserve better than being profiled by algorithms descended from slave passes and lantern laws. They deserve schools that nurture rather than criminalize, that invest in their futures rather than their containment.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.