Does the Angola Prison Farm Line Lawsuit End Modern Slavery?

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a single playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

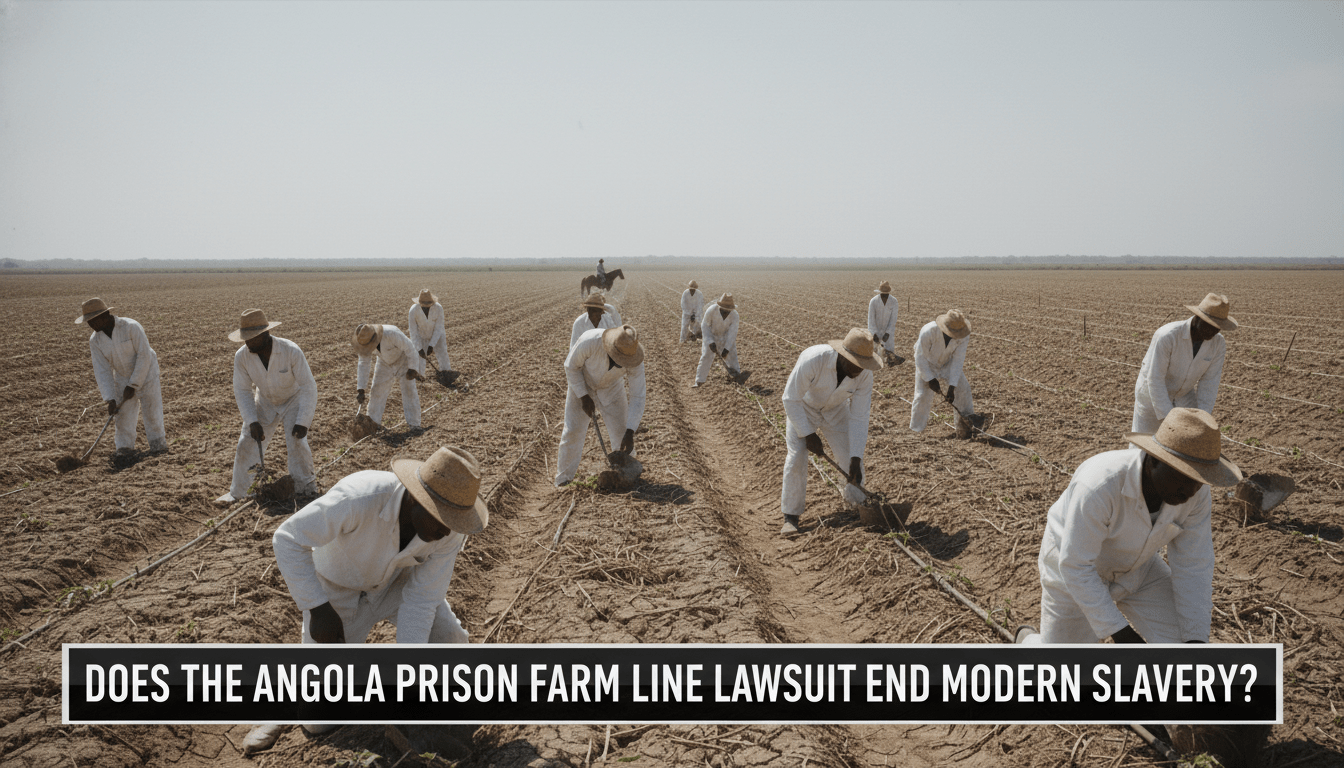

The Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, is currently facing a massive legal challenge that reaches back to the days of the Old South. A federal lawsuit regarding the Angola prison “Farm Line” is moving toward a major trial in 2026. This case asks if forcing incarcerated people to work in extreme heat is a violation of the United States Constitution. For many people, the Farm Line is not just a job assignment. It is a modern version of the plantation system that existed before the Civil War. The court must now decide if these practices can continue in a world with rising temperatures and evolving human rights standards (clearinghouse.net, theappeal.org).

The lawsuit is officially called Voice of the Experienced (VOTE) v. LeBlanc. It highlights the dangerous conditions on the 18,000-acre property in West Feliciana Parish. Men are forced to labor in fields where the heat index often goes above 100 degrees. They do this work under the watch of guards on horseback who carry high-powered rifles. The plaintiffs argue that this environment is designed to break the spirit of the workers. As President Donald Trump leads the country, the eyes of the nation are on Louisiana to see how it handles this intersection of labor, race, and punishment (therealnews.com, rightsbehindbars.org).

Angola vs. Louisiana Demographics

Source: SOURCE-3, SOURCE-5

The Dark History of the Land

The history of Angola begins long before it became a prison. The land was once a collection of cotton plantations owned by Isaac Franklin. He was one of the most successful and brutal slave traders in American history. The name “Angola” comes from the African country where many of the enslaved people on that land were originally taken. This connection to the transatlantic slave trade is a central part of why the prison is often called the “Alcatraz of the South” (humantraffickingsearch.org, ambrook.com).

After the Civil War ended slavery, the land changed hands but the labor system did not truly disappear. A former Confederate Major named Samuel Lawrence James purchased the land. He took advantage of a specific loophole in the 13th Amendment. This amendment abolished slavery except as a punishment for a crime. James started the “convict leasing” system, where he rented prisoners from the state to work his fields. Historians note that this system was often more deadly than slavery. Because the state did not “own” the workers, there was no financial reason to keep them healthy or alive (ambrook.com, theappeal.org).

The state of Louisiana took direct control of the prison in 1901. Public outrage over the cruelty of the James Lease forced this change. However, the state kept the same model of agricultural labor. Prisoners continued to plant and harvest crops by hand. This long history of historical racial injustices provides the foundation for the current lawsuit. The plaintiffs argue that the “Farm Line” is a direct continuation of this plantation legacy (humantraffickingsearch.org, ambrook.com).

What is the Farm Line?

The “Farm Line,” also known as the “Long Line,” is the primary work assignment for new arrivals at Angola. It does not matter if a person has a college degree or a specialized trade. Most people start their time at the prison in the fields. They move in rows across the massive acreage to plant and pick crops like okra, corn, and watermelons. They often do this work with their bare hands or simple tools. In some cases, they are forced to use Styrofoam cups or buckets to water plants instead of using modern irrigation systems (thelensnola.org, theappeal.org).

This labor is not just about producing food. Many people inside the prison describe it as a tool for social control. It is a way to prove who has the power. If a person refuses to work, they face a “Rule 8” violation. This can lead to serious punishments. These include being placed in solitary confinement or losing the ability to call family. It can also mean losing “good time” credits, which keeps people in prison longer than their original sentence. The state claims the work teaches “good work habits,” but prisoners argue the work is often pointless and humiliating (therealnews.com, theappeal.org).

The visual appearance of the Farm Line is striking. It looks very similar to images of the 19th-century South. Large groups of Black men work the soil while armed guards, usually white, watch them from horseback. This imagery is a major point in the lawsuit. The plaintiffs say this setup is designed to simulate the dynamics of chattel slavery. They argue it is a form of punitive social control rather than a way to help people return to society (ambrook.com, theappeal.org).

The Battle Over Extreme Heat

Climate change has made the work on the Farm Line even more dangerous. Louisiana summers regularly see heat indices over 100 degrees. For hours every day, men work in the direct sun without much shade. The lawsuit claims that the state shows “deliberate indifference” to the health of the workers. In 2024 and 2025, federal judges had to step in. They issued orders requiring the prison to provide water, rest breaks, and sunscreen when the heat reached dangerous levels (rightsbehindbars.org, promiseofjustice.org).

A key part of the case involves the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Many people in prison have chronic health issues like high blood pressure or mental health conditions. They take medications that change how their bodies handle heat. These medications can stop the body from sweating, which makes heat stroke much more likely. There is a specific “ADA subclass” of prisoners in the lawsuit who are at extreme risk of dying in the fields. The court has found that the prison had “glaring deficiencies” in how it protected these vulnerable individuals (promiseofjustice.org).

The struggle over heat is also a struggle over the basic right to survive. When the body cannot cool itself, organs begin to fail. The state argued in court that the work is necessary for the prison to function. However, the plaintiffs point out that modern machinery could do the same work without putting lives at risk. The refusal to use machines suggests the labor is more about the punishment than the productivity of the farm (theappeal.org).

The Economics of Labor

Louisiana law allows the state to take up to 75% of earnings for “costs of incarceration.” (theappeal.org)

The Financial Realities of Forced Labor

While the state claims the farm is about rehabilitation, it is also a business. An entity called Prison Enterprises manages the labor and sales at Angola. In recent years, this organization has reported tens of millions of dollars in annual revenue. The food grown at Angola does not just stay in the prison kitchen. Investigations have linked cattle raised at the prison to the supply chains of global companies like Walmart and McDonald’s. This means the labor of incarcerated people contributes to the global economy (ambrook.com).

The workers themselves see very little of this money. Most people on the Farm Line earn between two cents and twenty cents per hour. Some workers do not get paid anything at all for their first three years of labor. Even when they do earn a small amount, the state takes a large portion back. Louisiana law allows the prison to deduct 75% of an inmate’s pay. These deductions cover things like court costs, medical fees, and the cost of being in prison. Many people end up with nearly zero dollars in their accounts (therealnews.com, theappeal.org).

This financial system makes it almost impossible for people to save money for when they are released. It also prevents them from buying basic needs like soap or stamps while they are inside. The state argues that the farm helps make the prison “self-sustaining.” However, critics say this is a form of “administrative enslavement.” The prison uses administrative rules to extract labor for profit while keeping the workers in poverty (theappeal.org). This debate connects to larger federalism issues regarding how much power states should have over the lives of their citizens.

The Legal Loophole and the 13th Amendment

The center of this legal battle is the “Punishment Clause” of the 13th Amendment. This clause is what allowed the “Black Codes” to flourish after the Civil War. These codes were laws that targeted Black people for minor offenses like “vagrancy.” If a person could not prove they had a job, they were arrested and forced to work for the state or private companies. This created a cycle where freedom was constantly under threat for Black citizens (humantraffickingsearch.org, ambrook.com).

In 2022, there was an attempt to change the Louisiana constitution to remove the word “slavery.” This ballot measure was called Amendment 7. However, the final version of the bill became very confusing. The lead sponsor of the bill eventually told people to vote “no” because the language had been changed too much. He feared the new wording might actually give the state more power to force people to work. As a result, 61% of voters rejected the measure. This left the old language about slavery as a punishment intact (lasvegassun.com).

The failure to pass Amendment 7 shows how difficult it is to change the legal status of prison labor. It also highlights the ongoing Black Power struggles within the legal system. Without a clear constitutional ban on forced labor, the courts must rely on the 8th Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” This is a much harder standard to prove. The current lawsuit is a major test of whether the courts will finally close this loophole through a ruling on the Farm Line (clearinghouse.net, prisonlegalnews.org).

Key Moments in the Struggle

Source: SOURCE-2, SOURCE-5, SOURCE-6

Resistance and the “Heel String Gang”

The fight against conditions at Angola is not new. In 1951, a group of 31 incarcerated men took a desperate stand. They were being worked so hard that they decided they could no longer continue. They used razor blades to slice their own Achilles tendons. These men became known as the “Heel String Gang.” This act of self-mutilation was a protest against the extreme brutality of the farm managers. It forced the state to investigate the prison and lead to some temporary changes (ambrook.com).

Resistance also happens through the legal system. Incarcerated people have been filing lawsuits for decades. They challenge everything from the lack of medical care to the use of solitary confinement. However, the current lawsuit is different because it is a “class action.” This means the ruling will apply to thousands of people at once. It also specifically targets the “Farm Line” as a whole system. This is a more powerful way to bring about change than filing individual complaints (clearinghouse.net, prisonlegalnews.org).

The spirit of resistance continues today through the advocacy group VOTE. This organization is led by formerly incarcerated people who understand the system from the inside. They are pushing the court to see that the Farm Line is not just a job assignment. They believe it is a violation of human dignity. This case is part of a larger movement to rethink how the United States handles crime and punishment in the 21st century (therealnews.com, promiseofjustice.org).

The Road to the 2026 Trial

As the trial date in February 2026 approaches, both sides are preparing their final arguments. The state will likely argue that they have already made changes to provide water and rest. They will say that the farm is necessary for the security and budget of the prison. They believe that a court order to stop the Farm Line would be an overreach of judicial power. They want to maintain the status quo that has existed for over a hundred years (theappeal.org).

The plaintiffs will bring in experts to talk about the dangers of heat and the history of the land. They will show that the work is not helping people prepare for life after prison. Instead, they will argue it is causing permanent physical and mental harm. They are asking the judge to issue a permanent injunction. This would force the prison to stop using the Farm Line in its current form. It would be a historic victory for the rights of incarcerated people (rightsbehindbars.org, promiseofjustice.org).

The outcome of this case will have a ripple effect across the country. Other states like Alabama and Texas also have prison systems that rely on forced agricultural labor. If the court rules against Louisiana, it could lead to similar lawsuits in those states. This case is a “major test” because it could signal the end of the plantation model of incarceration in America. It is a moment where the past and the future meet in a federal courtroom (therealnews.com, prisonlegalnews.org).

Conclusion: The Future of Prison Power

The Angola prison “Farm Line” lawsuit is about more than just heat and okra. It is about whether the United States is willing to finally move past the legacy of slavery. For over a century, the state has used a constitutional loophole to extract labor from Black men. This system has survived public outcry, physical protests, and political shifts. Now, the federal courts have a chance to decide if this system is compatible with modern standards of “cruel and unusual punishment” (theappeal.org).

This case also touches on how society values the lives of those who have been convicted of crimes. By forcing people to work in life-threatening heat for pennies, the state sends a message about who belongs in our community. The fight to end the Farm Line is a fight for the basic human right to be treated with dignity. Whether the court rules for the state or the prisoners, the “Alcatraz of the South” will never be the same again. The trial in 2026 will be a defining moment in the history of justice in Louisiana (therealnews.com, rightsbehindbars.org).

About the Author

Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College, where he has been teaching for over 20 years. He is the founder of African Elements, a media platform dedicated to providing educational resources on the history and culture of the African diaspora. Through his work, Spearman aims to empower and educate by bringing historical context to contemporary issues affecting the Black community.